Golan Levin: So tonight it’s now six o’clock April 26, 2021. And it’s my terrific pleasure to introduce our next speaker, Marina Kittaka. Marina Ayano Kittaka is an artist and a video game developer best known as the co-author of the Anodyne series and Even the Ocean. She also wrote the essay Divest from the Video Games Industry!. Through developing tools like Zonelets, Marina dreams of a decentralized and vibrant Internet culture, the stolen birthright of the modern human-loving introvert. She sees a future where corporate social media sites are dry and desolate wastelands filled only with links to other sites that we actually enjoy. Folks, Marina Kittaka.

Marina Kittaka: Hello. Thanks so much, Golan. Let me just start my presentation here, and screen share.

Okay. Alright. Hi everyone. I titled my talk “Why is this the world?” because that’s…the energy that I’ve been feeling lately. Why is the world the way it is? I don’t know. I’m not going to answer that here totally, but I’m going to have that feeling.

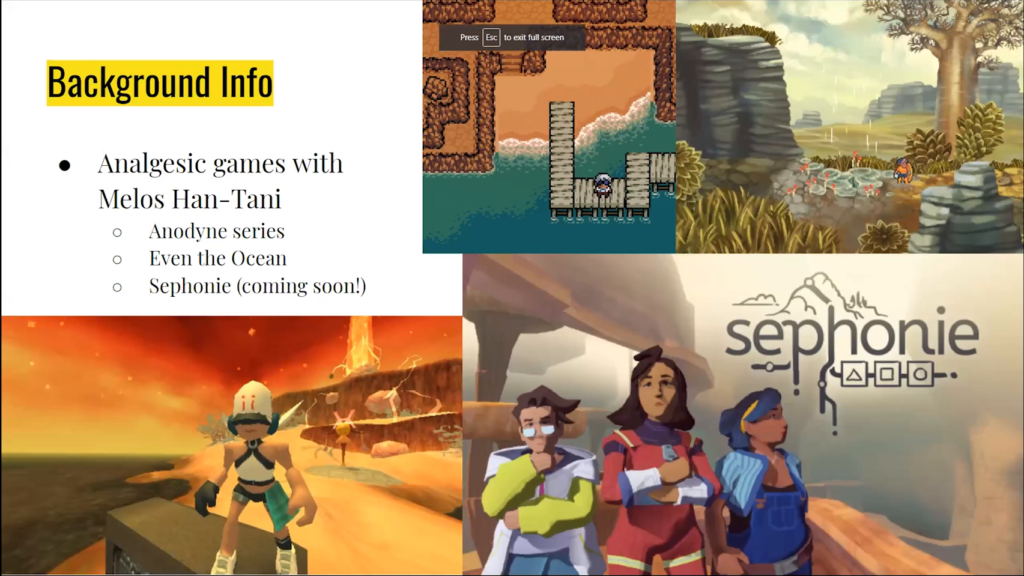

Starting off, yeah, I’m Marina as Golan said. I’m part of a duo with my friend Melos Han-Tani. And we are Analgesic Productions. So we’ve made the Anodyne series, Anodyne 1 and 2, Even the Ocean, and we’re currently working on our next game Sephonie, which is about three shipwrecked Taiwanese scientists exploring and researching a cave network full of fantastical species. And yeah, I’m very excited about that, and that will be coming up this year.

Generally our games involve exploring dream worlds filled with action and puzzles, strange humor, and meditations on the human capacity for change. And as a two-person team, Melos and I have to think really deeply about kind of understanding ourselves as artists, as creators, thinking about what tools we have access to and have the time and interest in learning, and the kind of moment that we live in. The way that things are structured around us. Because it’s a really big limitation to…in certain ways the only two people making games of the kind of type and scale that we do with these kind of worlds that you explore. And so we try to really have each project be very specific in how we approach it and use the limitations that we have to make something really specific as a result. Which is kind of reminding me of what Nathalie was talking about with tools, you can also have limitations just within yourself and do a lot with that.

So kind of as an example, in the bottom left corner, it’s Anodyne 2, the kinda orange screenshot. And that game was my first real project in 3D as an artist. And so there is a lot of like, jankiness to it and a lot of kind of blurry weirdness and odd shapes, and things where I was just learning how to use certain software. And we really played up on those qualities to create this kind of unsettling nature to the dream world.

And the process has been really different for Sephonie, which you can see in the bottom right. It has a lot more of a coherent art style, and it has a different tone to it as a result. And so we’re able to, and kinda have to tell a different story, as our experience with the tools change. And we have to either continue growing in certain ways or destabilize ourselves by trying something new, depending on kind of what we want to do with the feeling of the world. And I think that’s an interesting— The question about how do you manage perfectionism in yourself when you are kind of trying not to glorify protectionism in a way I think is a really interesting question that has a lot to do with my creative practice. Because it is like, you’re always trying to get better in some sense as an artist. It’s just inherently satisfying to do so. But at the same time, if you kind of do that without putting thought into it, a lot of the time you can either end up spending huge amounts of time on things, more than you would like to, or just saying different things than you maybe set out to say.

So the project that I was working at the open source residency is called Zonelets, so I’m gonna talk about the lead-up to that. Zonelets is a blogging software. But yeah, for the last several years I’ve been inspired by local and worldwide abolitionist thought, abolitionist kind of organizing and activism and thinking, which is kinda calling upon the historic abolition of slavery to now be thinking about abolition of police and prisons, borders, imperialism, and so forth. And I think that’s a really good example of people meaningfully asking why is the world like this? Why is this the world that we live in? And it’s become part of a really big conversation, particularly where I’ve been living, in Minneapolis after the murder of George Floyd.

So I was trying to think about how I could bring some of the influence of these thinkers into circles that I was already a part of. And that inspired the essay Divest from the Video Games Industry!. And that goes in a lot of different directions. I’m not gonna kinda summarize everything here, but it’s generally about how the narrative of technological progress and exceptionalism served to make the deep-rooted abuse and exploitation within the games industry appear palatable or even necessary. And I wrote why I thought that those narratives are misleading, and I brainstormed new ways of conceptualizing technology, progress, and worth.

As an example I’m gonna read a little quote about kind of the concept of technology and nicheness. And technology can really be very broad, but it’s telling I think— Well, I’ll just read the quote.

Computing power, massive scale, photorealistic graphics, complex AI, VR experiences that attempt to recreate the visual and aural components of a real or imagined situation… certainly these are all technologies that can and have grown in sophistication over time. But what The Industry considers technological progress actually consists of fairly niche goals that have been artificially inflated because capitalists have figured out they can make money this way. Notably, I don’t use “niche” here as an insult — aren’t many of the most fascinating things intrinsically niche? But when one restrictive narrative sucks all the air out of the room and leaves a swath of emotional and physical devastation in its wake… isn’t it time to question it?

What if humans having basic needs met is “technological progress?” What if indigenous models of sustainable living are “hi-tech?” What if creating a more accessible world where people have freedom of movement opens up numerous high-fidelity multisensory experiences?

Divest from the Video Games Industry!

So that was kind of part of the lead-up to Zonelets, the essay that I wrote back in summer of 2020.

So, later on I was wanting to blog. I had some different ideas for just various blogs I wanted to do, talking about video games, or talking about… I wanted to also do a blog about just like, word puzzles. I like little word riddles and puzzles. And so I wanted to be able to host this somewhere. I was very tired of Twitter as a site for communal learning. I think that you can get your foot in the door on a lot of different topics, but that the longer I stayed on Twitter the more I saw that it was structured to reproduce the same shapes of discussion over and over with just kind of the content switched out. And it ultimately didn’t feel like I was really learning about the specific things, I was just learning about how Twitter wants us to talk about things. And you know, the ways that those pressures are applied is shaped generally by the rich, by Silicon Valley, by advertisers, by white supremacy. And here’s a quote from the Zonelets web site:

These sites take the thoughts, care, and energy of people and consume them to grow the platform. It’s not satisfying to browse a person’s old writing, both because of the site’s user interface and because of the style of writing that the platforms encourage. So the process of ideas evolving and practices developing is obfuscated to create a dogmatic, eternal present.

So, I wanted a platform that I felt agency over and that other people could feel agency over, where it felt like it was yours and you could tend to it and invest in it, and have something to look back on as maybe a log of growth and change and of remembering how ideas were formed.

And that reminded me of this part from The Little Prince, if you’ve ever read that book. In the beginning he starts out on an asteroid with a rose, a single rose who he loves and he takes care of and he tends to. Later on he has gone to Earth and sees a garden full of many many roses and he feels kind of embarrassed and is like, “Oh, I thought my rose was special but there’s actually lots of other roses,” and feels kind of bad about that. But then later on, he comes to feel this quote.

Of course, an ordinary passerby would think my rose looked just like you. But my rose, all on her own, is more important than all of you together, [speaking to the roses] since she’s the one I’ve watered. Since she’s the one I put under glass, since she’s the one I sheltered behind the screen.

Right before I made Zonelets, I made a little personality quiz that tells you which Ninja Turtle you are. And it was made to see how people in my circles on Twitter and Facebook felt about HTML and CSS and coding and blogs. And so basically I ranked the turtles in order of nerdiness, with Rafael to Leonardo to Michelangelo to Donatello, being least to most nerdy, and then kind of ranked these different questions based on that. Some of the questions were very straightforward about like, have you used HTML, have you used CSS, are you interested in blogging.

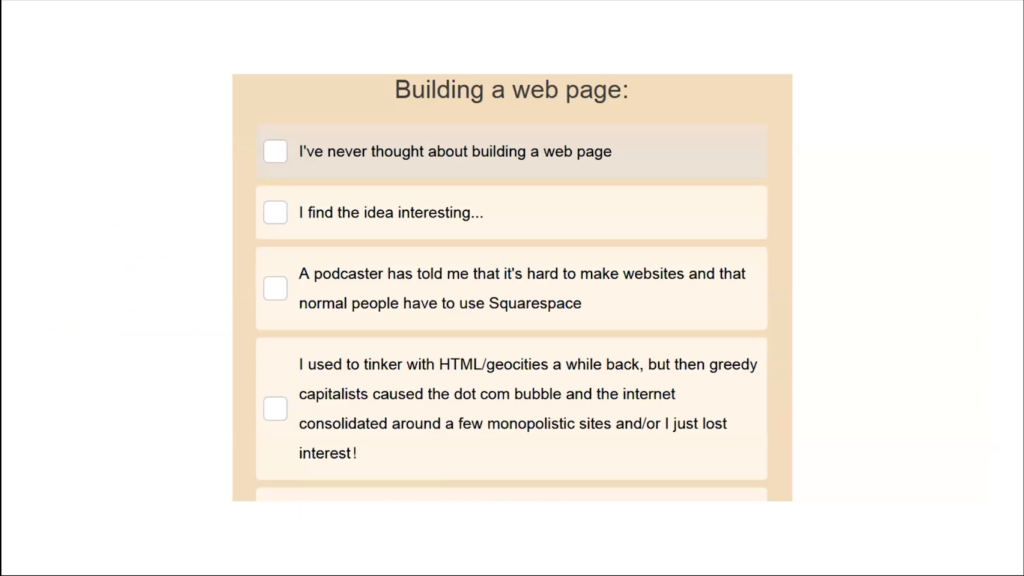

And then some of them were also just kind of cheeky. And I’ll just read this.

Building a web page:

* I’ve never thought about building a web page

* I find the idea interesting.

* A podcaster has told me that it’s hard to make websites and that normal people have to use Squarespace.

* I used to tinker with HTML or Geocities a while back, but then greedy capitalists caused the dot com bubble and the Internet consolidated around a few monopolistic sites and/or I just lost interest.

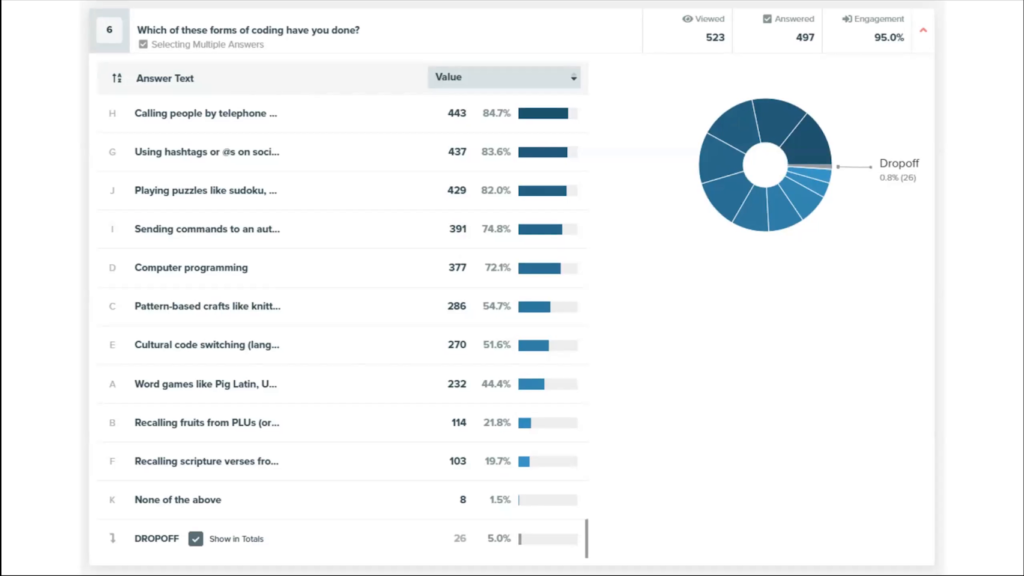

This was another question, which unfortunately the answers are kind of cut off, but this is the view of the software that I got a free trial of that shows you the data of people’s responses. But this was another kind of cheeky question that was “Which of these forms of coding have you done?” And I just tried to brainstorm a lot of things in kind of everyday life that I was familiar with or that I had heard of that in my mind felt basically equivalent to what I would be asking of people who are using Zonelets. Because using Zonelets requires writing HTML. And so some of the examples of coding that I put here are calling people with a telephone number, using hashtags, playing Sudoku, sending a command to an automated text thing like “Stop,” knitting, code switching in language, recalling scripture verses. Various things like that. And so I don’t know, I think it’s interesting to use a quiz—not really scientifically but just as a way of thinking and as a way of communicating, and as a way of just having fun with people.

Zonelets. So here we get to the actual project.

Basically Zonelets is a template for people to just kinda copy a file structure, and then they can make a blog post. And they do have to write the HTML, but starting out it’s pretty simple because you’re just copying stuff over, and then if you’re just having text you just have to enclose each paragraph in a P tag. And it’s not that hard to get started with but it is kind of intimidating if you aren’t familiar with coding or with HTML.

And so really what I saw kind of as the project of Zonelets was the narrative around it and the framing of it on the web site of Zonelets. And so that was kind of the work I was doing as much as the code itself. Here’s a quote from the Zonelets web site:

Plenty of services can help you to “create a professional-looking website without writing a single line of code.” Now, thanks to Zonelets, you can create an UNPROFESSIONAL-looking website by writing NUMEROUS lines of code!

And then I kinda say like, wait wait wait, come back. And later on I say,

[Here’s] a metaphor: plenty of people know very little about cooking, but most people could cook and eat an egg. Imagine living in a world where if you craved eggs, your only options were to nab a fast food breakfast sandwich ([which is] like social media) or go out to an expensive brunch ([which is] like a premium website builder)! Both of those options have their place, but wouldn’t it be unfortunate if it were kept secret that most people could literally just fry an egg themselves?

Sure, parts of the internet can be very structurally complex. But Zonelets is the “fried egg” of the internet. Making text appear online is both utterly basic and infinitely powerful. If you write something down, and someone else reads it from afar… that’s it! That’s the whole thing! You’ve done it! And no amount of complexity or polish or professionalism or engagement metrics or dopamine-hijacking frameworks could ever replace that.

So that’s the sort of way that I was trying to frame and talk about the idea of using Zonelets so that the things that maybe looked hard would feel less hard.

The paint and sip metaphor is another way that I think about Zonelets, which is that there’s those activities where you can go with their friends and paint while drinking wine or whatever and follow along with an instructor. And I kinda think that Zonelets could be like that, where you’re setting up a web site. I have a whole video tutorial and text tutorial that you can follow along with. And it’s kind of like a little activity that you can do, and you’re not necessarily going to learn how to be a professional web developer but you’re gonna understand maybe something about the Internet in a way that you didn’t before if you aren’t familiar with that. And I think that’s really interesting and that’s really special because the Internet is all around us and such a big part of our daily lives.

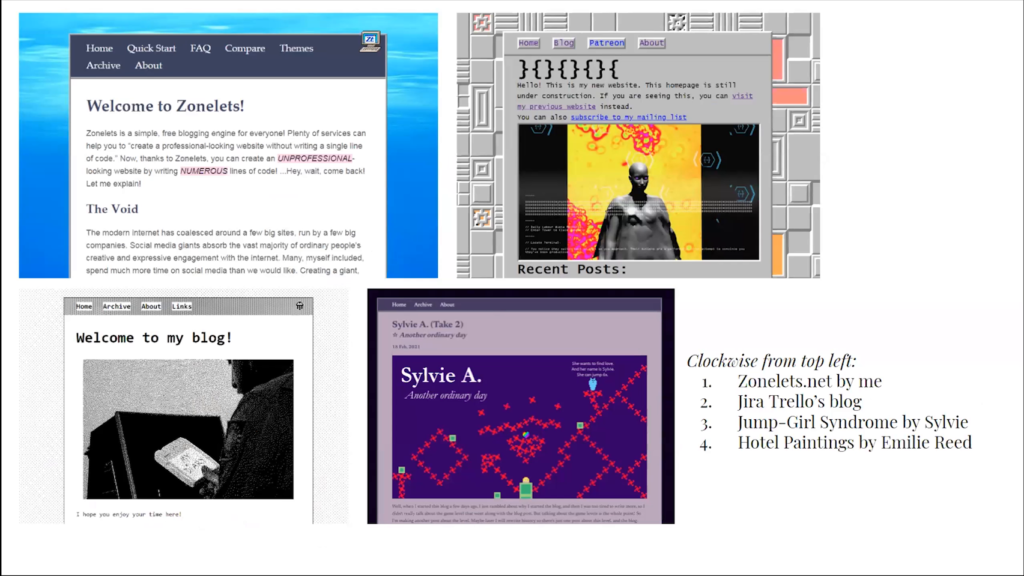

Here are some examples of what Zonelets looks like. There’s the Zonelets home page in the top left that I was talking about. And that’s a very kind of basic theme, what it generally looks like. And then there are some custom themes that other people have made. There’s Jira Trello’s blog in the top right, with a really cool theme. In the bottom left, Hotel Paintings is this one-bit dithered theme, really cool by Emilie Reed who also is probably the most prolific user of a Zonelet blog. Very good writing. Sylvie made this really cool blog/game. And actually Emilie Reed has also put games on some of the blog posts. But this, Jump-Girl Syndrome, specifically each blog post is a level of a game. So the game as a whole is kind of the blog, and there is a level and then text kind of about the level. And that’s a really interesting and exciting idea. I really like seeing cool things like that coming out of the work that I did. It was very exciting.

And there’s something that I get into in detail in my writing as I talk about all these different issues but that might get lost in kind of a summary, is I feel like it’s really easy to fall into these kind of false dichotomies between this kind of idea that oh, the high-quality stuff, the industry stuff, that’s like high-quality. That’s like…good; it’s well-made. But it is bad. But it is evil in some sense. And the alternative stuff, the scrappy stuff is low-quality but it is morally good.

And I think that this is kind of an unnecessary framing for multiple reasons. First it kind of like… You’re kind of ceding a lot of ground already to assume that— Well, I should follow along with my bullet points here. So like yeah, this idea of like “alternative” as a genre. Like whatever is in the mainstream is one sliver of kind of all of human existence and the way that people can think and create and be at any given time. And that’s something that becomes very clear, especially if you look globally or if you look into history. But I think that’s kind of part of why a lot of our current industries are very antagonistic towards preservation of the past. But it becomes very clear that okay, so people are doing things in this particular way but “alternative” is not one thing, it’s like, everything else.

And secondly it creates this sort of fetishization of authenticity in pain and trauma. And that can create this pressure release valve that substitutes for actual change and justice, and creates this fighting-over-scraps mentality where someone who is kind of outside the mainstream or part of a marginalized group is seen as having this sort of low-quality but morally correct substance to their art, which then that sense can be easily tokenized and brought into the mainstream just as much as the mainstream desires to kinda defang it.

And it’s really unnecessary, because there’s things that people are doing— Like, if anything has value, it’s for reasons. There’s no secret law governing behind the scenes that something is like, good because it’s bad or anything like that. If something is good then it’s good.

Sorry, I’m getting very…lost in the weeds here.

The third bullet point is it situates moral and political struggle at the point of individual consumer choice, which is something that I think happens a lot with social media that I think is kind of just sort of tiring. Like…I feel like people broadly have projected a lot of judgment on themselves and other people about our individual choices when it really should be about our collective demands. It should be about what we want. Because most people have more in common in terms of what our struggle is. The people who are in power are very few. And so it’s like whether you prefer Call of Duty or Anodyne, we should all have housing and healthcare and a habitable planet. And so I really think that we can do a lot to not think about things in that way.

So yeah, thank you to Golan and everyone who has helped me with this talk, and all the fellow residents. It’s been really exciting to be a part of this. And I feel like I spent 2020 having a lot of big ideas, and now my goal for 2021 is to have no ideas, and to accomplish nothing of importance.

And here are some of my influences on here. And I think that’s it for my talk. Thank you so much.

Golan Levin: Thank you so much Marina for this really beautiful and considered talk. That was brilliant. Thank you.

One of the things that we’ve I think come across a lot in our residency program with the Open Source Software Tools for the Arts is the notion that developing tools is not only about the coding, right. But that there’s so many other kinds of work—labor—and other ways of contributing to open source software tools for the arts. And what we see in your Zonelets project is quite interesting because so much of the real deep consideration here has to do with the framing, as you said. That you spent your time thinking about how to position this. I think that real work is required to come up with the fried egg metaphor, or the paint and sip metaphor. Like, it takes a kind of…the work of developing an outside perspective on something when the rest of us are the fish inside the water, right.

So I wonder if you could maybe say a word about other cases where you’ve seen someone’s framing that you really admire, or what led you to this realization that framing is where the differential effort for you is.

Marina Kittaka: Oh. Thank you, that’s a good question. I think what… I’m not sure if I’ll be able to come up with an example offhand. But I think the way that I approached it was really that— So I’ve always been more kind of an artist, coming at things from an artist’s perspective. But I did in high school and college, before I was sure what I was going to be doing with my life, I was really exploring web design as a possible career path. And I think I always found it extremely…stressful and hard. And there are all these…there’s kind of like a machismo to. Like especially web design and graphic design. There were all these like things that I built up in my mind of like oh, you look stupid if you do this. Or it’s really hard to do responsive design, which it kind of is in certain ways. But also if you make something super super simple, that just is almost just blank HTML, then it’s not that hard to make it responsive. And to make it accessible.

And so in the years since, when I didn’t have that pressure of like oh, am I gonna have to become a professional web designer, I had tried out doing little things with web design and with graphic design, and I realized that oh, a lot of that machismo and a lot of the things that made things really scary were really just blocking me from doing simple things that matter to me, and that could matter to someone else.