Golan Levin: Everest Pipkin is a drawing and software artist from Central Texas who produces intimate work with large data sets. Through the use of online archives, big data repositories, and other resources for digital information, they aim to reclaim the corporate Internet as a space that can be gentle, ecological, and personal. They hold a BFA from the University of Texas at Austin, an MFA from Carnegie Mellon University, and have shown internationally at the Design Museum of London, the Texas Biennial, the 21st Triennial of Milan, the Photographer’s Gallery of London, the Center for Land Use Interpretation, and other places. They for their OSSTA residency this semester have been developing a large list of tiny tools. It’s my pleasure to welcome you to Everest Pipkin.

Everest Pipkin: Hello. Thank you so much for having me. I am really really pleased to be here. Let me go ahead and share my screen, and give me that brief moment to switch over as always. Share; play; great. Let me pop out the chat so I can see if there are questions.

Yeah. I’m Everest. Thanks for having me. It’s a joy to be speaking to this community in particular, because again, Carnegie Mellon is a place I’ve spent a lot of time. Pittsburgh, very close to my heart. It’s nice to be here, even virtually. In general I work with data sets, “big data,” but with the full knowledge that this is only ever the lives and experiences of people bundled up and repackaged through processes angled for usefulness or at the very least posterity. My work both in off- and on-line spaces kind of looks at all that as simply all that human life, the ways in which this immensity of access to so much human creativity through time is a gift. And, like so many gifts of abundance, one that has been commercialized in corporate capitalistic structures, or in research including towards surveillance and weapons research, and how this acts on all of us. But we’ll get to that in time.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=C_aVhdK4MyI

I like to start lectures with an old YouTube video. I switch them around, but it’s often this video from 2008 called “tom willey, bicycle man,” which is about 144p, fifteen seconds long. I’ll just play it.

There’s nothing particularly special about this video, although I do like it. I like the compression artifacts from an old cellphone camera and the low-bandwidth kind of era of YouTube. I like its brevity. I like the quality of kids just goofing off in a park. I like that it only has about a thousand views. Pretty sure half of them are me.

To me it feels like this kind of ephemeral and beautiful, crystalline moment, of which there are sort of moments still captured on YouTube of this era. And it’s still online, thirteen years later. But the world has really shifted around it. The Internet doesn’t feel this way anymore.

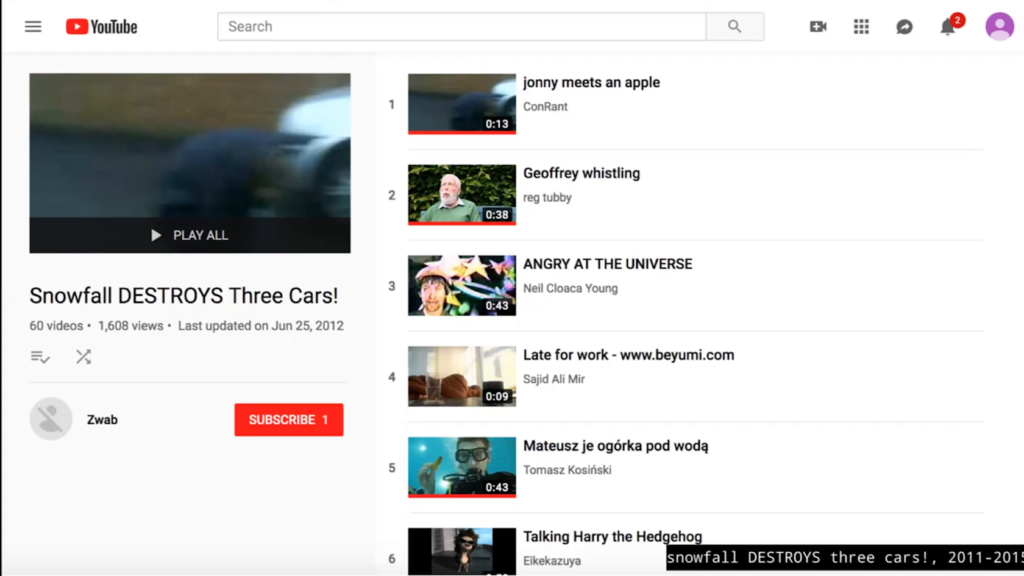

This video is part of a YouTube screening series that my collaborator Zoë Sparks and I started in 2011. This curatorial YouTube series called Snowfall DESTROYS Three Cars, which is named after a video that’s since been taken down was really interested in these kind of delicate and intimate corners of YouTube. We’d independently developed a habit of saving compelling videos off while browsing. And after sharing some of our favorites with each other, we thought that it might be interesting to arrange them with particular care and screen them publicly in a room like a movie, to focus the attention of a crowd.

Although we screened this in several iterations between 2011 and 2015, the series eventually ended, as the YouTube sorting algorithm made it harder and harder to find that kind of video that we were really looking for. Those moments that were kind of captured out of someone’s life, shared willingly, important enough to end up in a public-facing repository. But not you know, intended to go viral, not intended to be something to laugh at but rather be something to sort of sit along with. We called this project an attempt to find and assemble aggressive moments of peak human detritus scattered most lovingly. Which might be an apt description for much of my work.

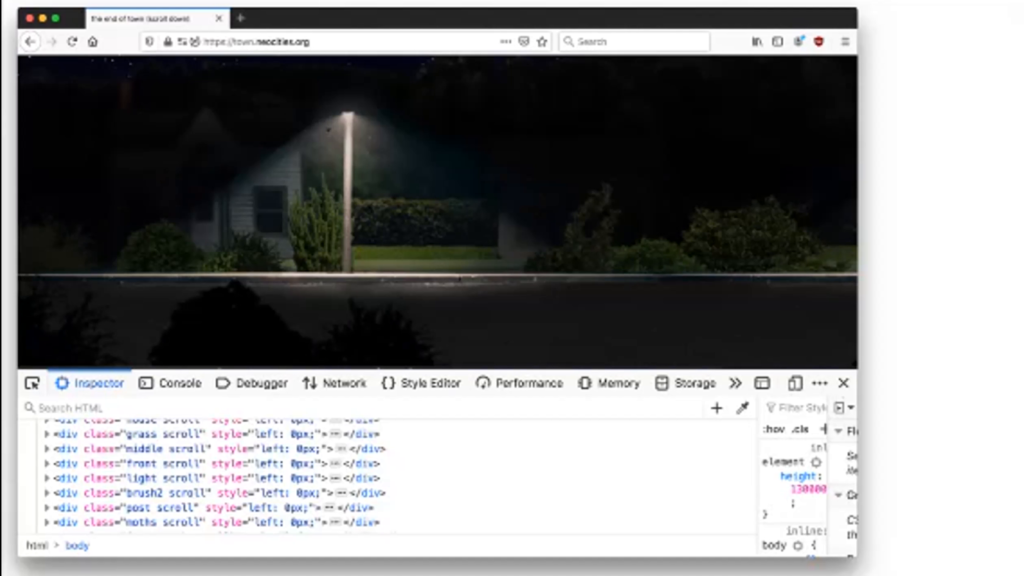

I didn’t study programming or computer science. I didn’t really even know that artists were making art with code until I was almost done with my undergraduate degree in painting. At the time, I was making these one-page painting-like web sites, which incidentally was right around the end of the net art nexus, which I didn’t know was happening. I’m not gonna dwell on any of these. I made them a long time ago. They feel simple and a little naïve now. But I wanted to bring them up because of their methodology of construction. Handmade mostly in HTML and CSS, code written directly in the text editor. A material understanding of the construction of “a web site” that felt much closer to my painting practice than the curatorial work with YouTube, despite their surface level of sharing digital space.

This methodology of making of course is not a rare way to engage with the Internet. The Internet is very much based on that idea of View Source, reading through how something was made, copying bits over, editing things, figuring it out. It’s how I learned to make web sites in my teens, haunting forums and home pages, and it was how the majority of the Internet was made then. Front-facing web sites that contained all of their information at the fore, human-readable, handwritten. But it’s an increasingly rare paradigm of construction.

Already in 2012 or 2013 when I was making these little domains this idea was nostalgic. I hosted several of these on Neocities, a Geocities-like web site builder that was thinking about this old Internet, that hand-built Internet, an Internet made mostly by individuals already ten years ago. There’s lots of problems with that, too. Particularly it’s difficult to access, its cost, its vision of what a default user was. I’m not advocating a return, or even really a nostalgia.

But as a touchstone, over and over I think about making those web sites as a painter. Learning to make them like I learned to paint, which was going to look paintings. Seeing how somebody else had done it, and how then accessing this type of sublayer was as simple as hitting Cmd‑U.

It’s something that I’ve never really been able to shake. The feeling that one of the best parts of the Internet is how visible that substrate is, how apparent the hand, how it’s only ever just skin deep.

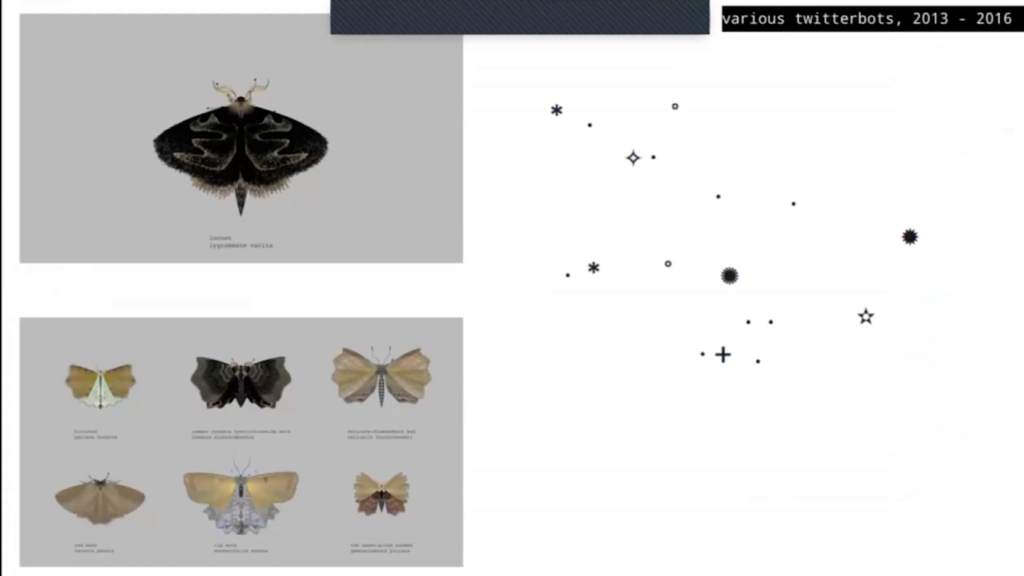

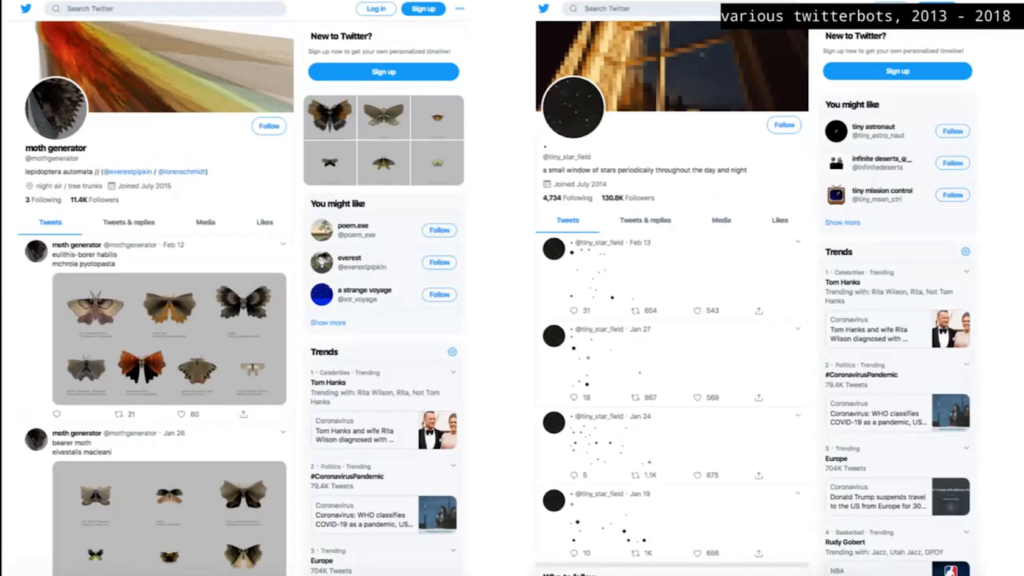

Around this time, I was also making Twitter bots. This is moth generator, to the left, @tiny_star_field to the right. Both of these live on Twitter still. Although…they run on my laptop so it does kind of depend on me remembering to restart the cron jobs every once in a while. I’m producing intermittent works for the timeline.

Again, I’m not going gonna dwell on these. They feel [sighs] very old to me, and naïve. But when I would talk about this work at the time, I would talk about it like this: devoid of space; images and code without context.

But how it actually looks is this. Entirely within the context of Twitter, presented with news, sidebars, suggestions that are all tailored to me. Alone. Alone of my power and conviction to that space. One that hides all of the internal logic of those programs behind the server-side interface of a tweet towards corporate gain.

When you begin to see your work as situated within this specific corporate context, you of course start to look at what could be made or used outside of it. Which is what led me into making work both with and for the public domain. This is a screenshot of the Biodiversity Heritage Library, which is one of many many many resources online full of public domain images and texts.

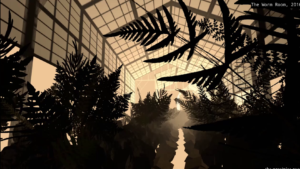

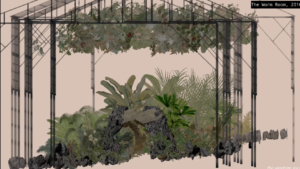

I used botanical illustrations from this collection as the basis for my 2016 game The Worm Room, which is a first-person exploration game and digital interactive artwork kind of set in this series of endless glass greenhouses, each generated as it’s walked into. You can sort of see all the little cutouts of the botanical illustrations, which form the basis of sort of the landscape of the space.

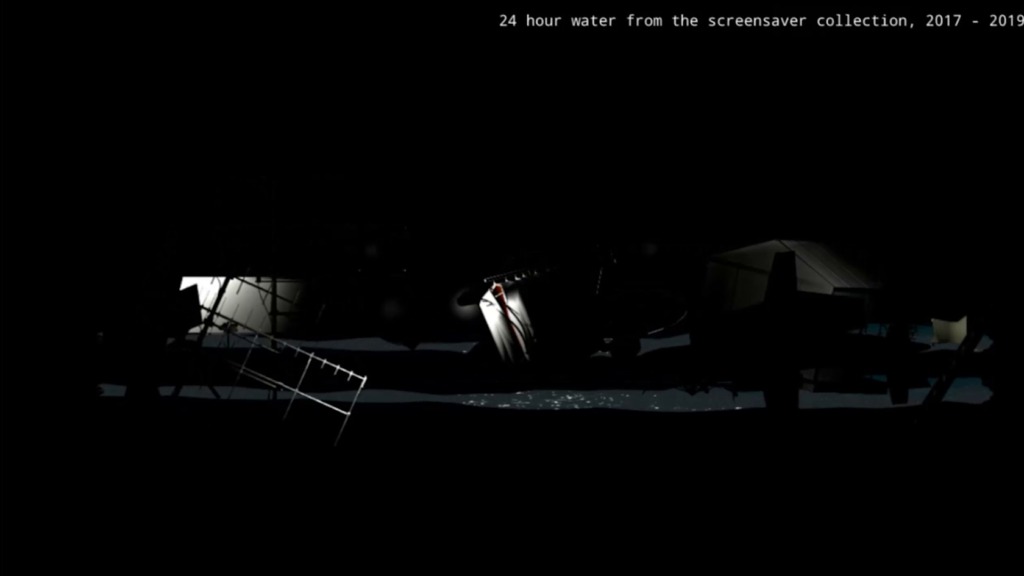

Working with models like this and in game engines in general, I became very focused on the labor and many lives of those pieces. Who made them. Where else they’d been used. How many alterations they’ve seen. How many concurrent screens they’re on. How many times they’ve sort of been downloaded and shifted just a little bit and reuploaded. How many human hands have been attached to these material objects which have been disseminated so widely through Internet space. I began to collect and situate these Creative Commons 3D models in a series of screensavers and generative video works, thinking about what they would be like given agency.

This isn’t of course different than how these models get used in general. This is why I love assets for collage, and flat games, and games made in pre-existing tools, games made quickly out of the curation of so much already-existent care and labor. The assembly of all that human life into a new thing. It is truly one of the best things about being on the Internet.

But I wanted to make things that let them spend time with themselves, if this makes sense. I’m interested in screensavers as performances for…an empty room? Like, they’re very ambient. They’re kind of works for the back of your head? But they’re live, they’re running in real time. They are understanding time in a way video work does not. And when they’re made of these objects that have material lives both inside and outside of that space, it suddenly takes on this other layer for me.

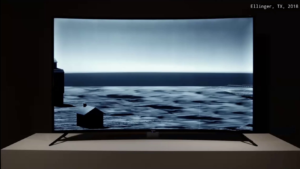

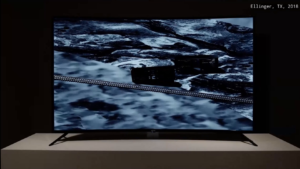

It was from the screensavers that I began to work on Ellinger, TX. This is a project that takes as a point of departure the real-world Ellinger, which is a rural community situated on the intersection of two major highways near where I grew up, very near where I’m living at the moment. Although once a farming town, Ellinger now makes the majority of its income in the town’s two gas stations. And like so many rural towns, it’s both dependent on and hollowed out by contemporary systems of economic traffic and opportunity.

In my work, Ellinger has been cut off from these highway routes as well as the rest of the world. The characters that live inside of this town are in this micro landscape sort of bordered in the same way that game spaces are surrounded by invisible walls. But they’re given time. The “people” in this place are given time to like live in this little micro universe that plays itself…kind of…characters unable to leave but also unable to be carried away.

I guess I made this work for a couple of reasons. Partly because I was interested in how the lived experience of mass-produced objects might give them weight. All the textures in this game are all hand-drawn and applied to these creative Commons models. What might happen when a place that survived because of network capital is cut off from that network, both the digital network of capital and the physical network of highways. And what happens when the transit network that so often works to carry individuals from a place is also removed and how that intersects with kind of game-like visions of walled or bordered spaces.

Right after this project, I did this long residency in Montello, Nevada, thinking a lot about the patterns of people, of movement as its own kind of network. I mentioned I think a lot or dream a lot about intimate Internets, Internets that push back against sort of like the bad landlord problem of corporate Internet spaces.

This was my experience of sending email while on a residency here, where the closest cell reception was a two-and-a-half hour walk up a mountain. Once a week I’d pack up my laptop and cellphone, do the hike, turn on my wifi hotspot, stick my phone up in a scrub juniper tree, and sit and return all the draft emails I’d downloaded and written a response to last time. All on about one bar of 4G, depending on the weather. And if I was really lucky I might get a podcast, too.

There was also, though, this hyperlocal network in the house, in form of a flash drive. So people left flowers and notes, which is by all accounts a sneakernet, right, an Internet that’s based on a physical location you carry around with your feet. And these two Internets in relationship to each other, like this broad Internet that I had access to but only kind of like…a mailbox that I had to take a long hike to get to, that was very physically dependent on the way the clouds rolled in on that particular day in the couple of hours that it had taken for me to walk from the house to the hill. As well as Internet that sat in the house all the time but that didn’t have access to the outside world, that’s population was entirely dependent on people that had physically been in that space before me and had dragged diary entries and recipes and whole series of anime onto this flash drive and left it in the house for next person. Sort of like a guestbook but you know, plus-plus-plus. And those two…like, alternating Internets both were like my lifeline while I was here. And have gone on to remind me of all the ways in which the Internet can be other than often the Internet that I experience as it is now.

There are lots of people who compute this way already, right. Who don’t have access to high-speed fiber optic cables, who have to go to an access point to get online, whose Internet mostly is hard drives passing around. This is absolutely the lived reality of many. It’s not like I had a unique experience in the woods. But it was useful for me, I think, as I was thinking about ways in which I could think about technology and tools and Internet spaces that were productive and under my control and for a small community.

This experience led into gift game which is an iframe poem about kind of files circulating in an Internet of hands, an Internet of gifts. It uses the technology of iframes to populate these little portals into other spaces, into other works, into moments inside of archives or onto blogs that sort of exist inside of this meta-poem, a look at maybe an alternative vision of the way hyperlinks could’ve once worked for us.

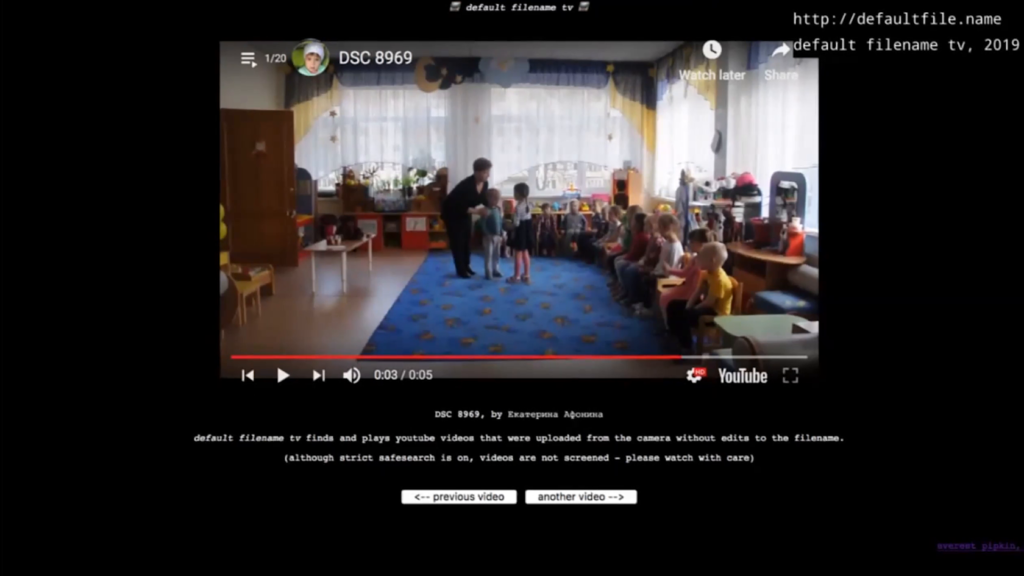

It also led into this project called default filename tv, which…as I was working on this I was thinking a lot about the casual nature of files dragged onto a drive. You know, so many of those files that were on that hard drive at that residency were just named you know, DSC_179, right, because like why would you name a file that wasn’t going to be indexed by a search engine.

So I made this YouTube aggregator which serves only videos that were uploaded directly from a camera without edits to the file name, so they all have titles like 1453.mov. And those small moments kind of point back to an era of YouTube that was intimate and personal and mundane. Like that video we watched at the very top of the lecture.

I started working on this partly as a personal tool to help find that early YouTube kind of video, those ones that no longer show up so readily in the search and recommendation system and have buried my capacity to continue that curatorial project with Zoë. I was originally planning to use it to curate videos from rather than produce a watching stream, but eventually I found the experience of loading a video one after another to be pretty compelling in and of itself. And this is because all of these videos share this particular quality, which they are…special enough that they desire to be saved, right, off of the device, off of the thing that was in your pocket. But are not necessarily made for…virality. They’re not made to be surfaced at the top of an algorithmically-sorted recommendation system that uses keywords and titles to index these things.

Instead they’re these moments that are…yeah, very personal and mundane and powerful, and remind me of an Internet that feels like one that we haven’t lost, but has been intentionally squashed because it’s hard to market on top of an Internet like this.

There’s something about…echoes, and memory in all of that work, really. Information made of data, which is always always just the actions and making of people, for better and for worse. Which does I think eventually lead you to thinking about neural nets. Most people know what a neural network is at this point. But in case you don’t, it’s a type of machine learning that models itself kind of after the human brain, learns patterns and then reproduces them.

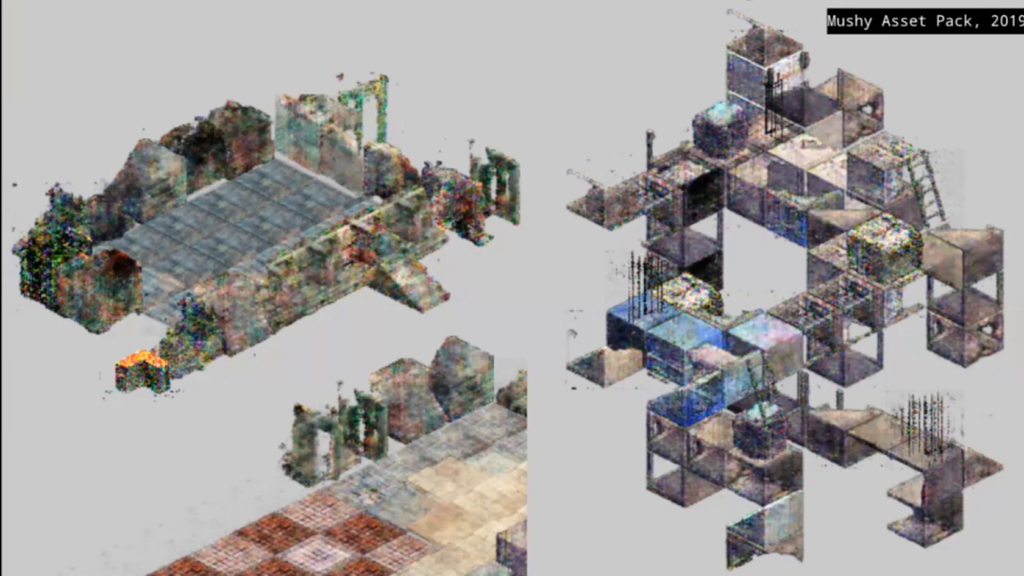

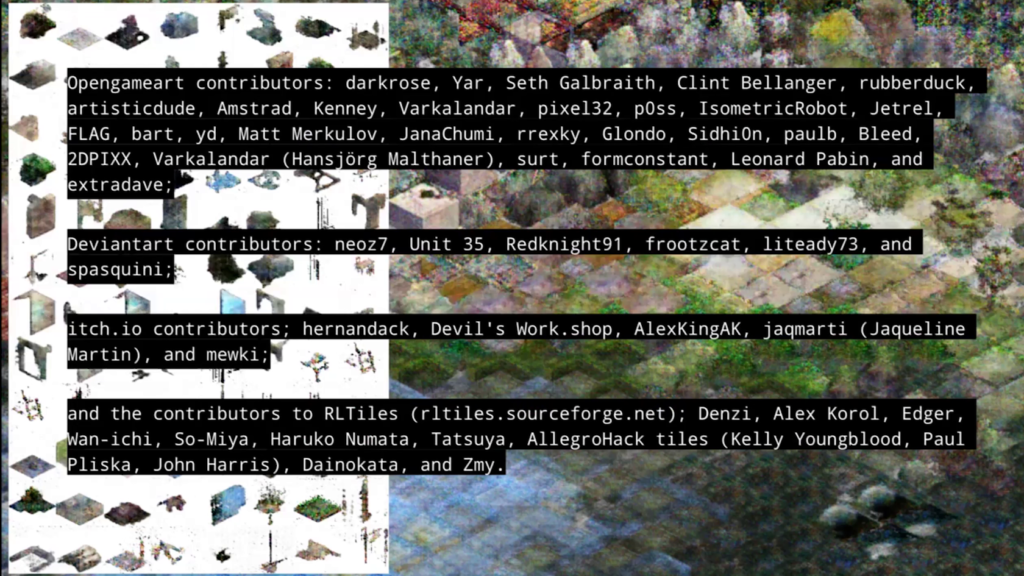

I made this asset pack in 2019. 824 neural network-generated isometric tiles. These are all generated on tiles that were from the Creative Commons. They have gone back to live in the Creative Commons. If you’d like to use these for a game, you’re welcome to. They’re on itch.io. But they lean really directly into sort of the fuzzy aesthetics of generative neural networks, although they have moved in leaps and bounds in only the two years since I finished the project. But you know, they’re sort of intended to let you build these like, cities and spires in these faded landscapes of kind of half-remembered conventions.

But of course, never empty, always peopled. These are the contributors who made the tilesets this was originally trained on.

Sort of off this neural network work as well as default filename tv, I proposed what would become Lacework in the summer of 2019. In my proposal I described a cycle of videos created from MIT’s Moments in Time Dataset, each of them slowed down, interpolated, and upscaled immensely into imagined detail, one flowing into another like a river.

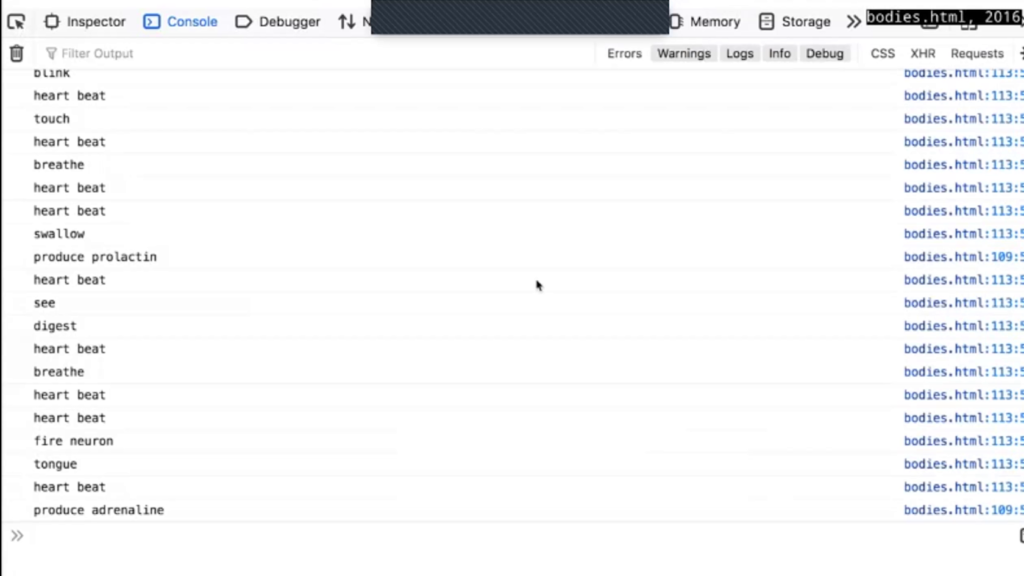

This project… MIT, the Moments in Time Dataset is dedicated to building a very large-scale dataset to help AI systems recognize and understand actions and events in videos. In many ways Moments in Time is unremarkable. Like so many datasets with similar goals, Moments in Time is intended to train AI systems to recognize actions. It contains one million three-second videos scraped from web sites like YouTube and Flikr, each tagged with a single verb like “asking,” “resting,” “snowing,” or “praying.”

There’s a couple things that are particular about Moments in Time. It tries to break down those possible actions into just 339 “doing verbs.” It also doesn’t clarify about the subjects in its videos, for instance. It’s more interested that something’s flying than whether that thing is a bee, a flower, a person, a satellite, a bird. It decenters human actions in favor of words that might apply to broader swaths of doing. But for the most part, it’s just a big dataset.

So, at first I decided I would obfuscate some of these videos. You know, I would take them down to this tiny, you know, like 20 by 20 pixel size and then upscale them over and over with a neural network, making these unfolding kind of slow videos full of all of these details.

But as I began to dig into this dataset, as I began to sort of try to write a process that would run on the whole thing algorithmically and create a subselection of videos, I began to realize that there was no possible way for me use this as it was. This whole project really messed me up, because I watched the whole dataset. I just didn’t know how else to do it. I want—I needed to understand it.

Working with material like this, one of the biggest things is credit. How do you accumulate the information of others at scale and still make it materially theirs? Not being made fun of, not being “elevated” but instead cared for. With my work with YouTube or with the Creative Commons tiles, I’m so careful always to go by the license that things were originally licensed by, the include the names of the creators of the work. default filename tv always includes a link back to that person’s channel. If they take that video down…you know, it all runs live, it never is indexed. Nothing’s ever downloaded. So, control rests within the hands of the original creator.

A dataset like Moments in time, which has got a million scraped videos from all sorts of sources, many of which gathered without consent…I don’t have that ability. I can’t actually find even where these things came from. They might not even be online anymore. And so I tried a lot of approaches to kind of get around this in other material ways, but I ended up just watching the whole thing.

I had kind of expected the act of watching Moments in Time to be…calming or exploratory, like seeing the world through a window. But this archive isn’t entertaining or poetic or beautiful or joyful, even though it contains many videos that evoke those feelings. It’s an archive with a purpose, an archive of actions for an inhuman eye. It says “Here’s the world, here are the things that are done here, terrible and great.” It feels very raw.

I ended up coming to see all these patterns in camera quality and shadows and the color of paint, the types of trees and movement and texture. What would unfold into more and more detail. As well as like, the way in which videos were gathered from their keywords, the way in which they were chopped and sliced, the way in which like, these three-second moments were cut out of a much longer video that would’ve been naturally uploaded by someone who you know, may have ended an action at a minute. I began to wonder if this was how a sorting algorithm feels.

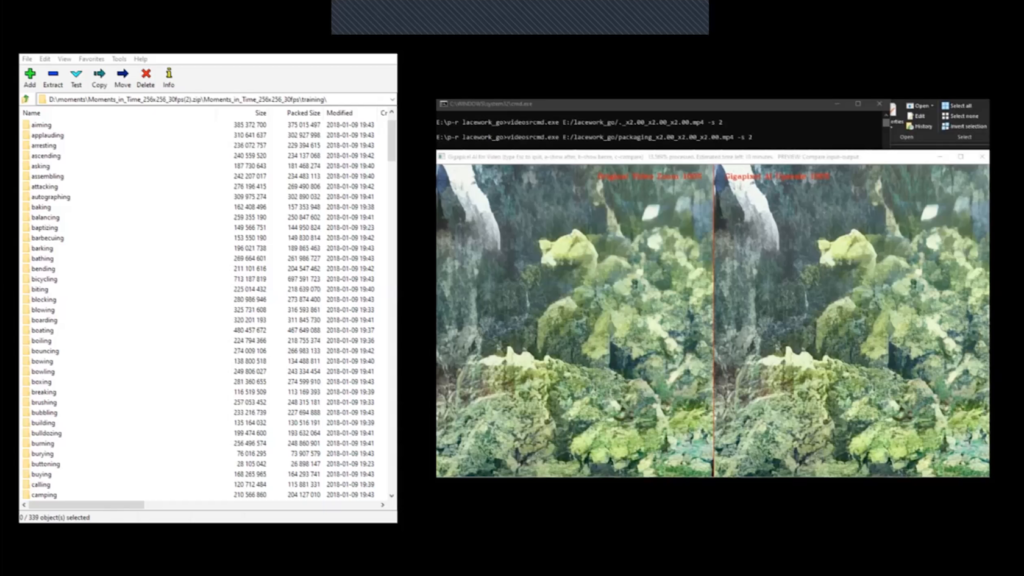

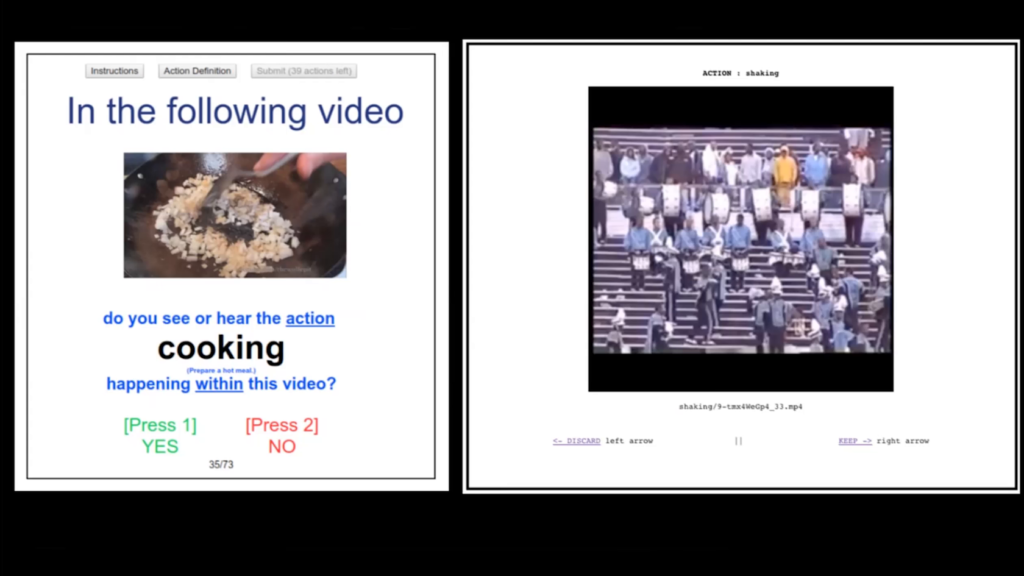

I ended up having to make this hand-made selection interface, because just going through the things in my file system was too slow. Mine is on the right. And on the left is the image in the Moments in Time whitepaper which is the original selection interface for these videos on Amazon Mechanical Turk.

I am probably the first person to watch all of Moments in Time, would be my guess. But even though I’m the first person to probably watch all of it whole cloth, every part of the dataset has had human eyes on it before. And this is because after being gathered, and downloaded, and cut, the videos of Moments in Time were automatically uploaded to Amazon Mechanical Turk for annotation.

Mechanical Turk is a crowdsourcing service—you’ve probably heard of it—that connects requesters to workers who generally perform small computer-like tasks for pennies. It’s owned by Amazon. It takes its name from this fake chess-playing automaton that hid a real chess master inside of it, which is…pretty dire. And without looking at the whitepaper, I had recreated the kind of exact interface that was originally used to select these videos.

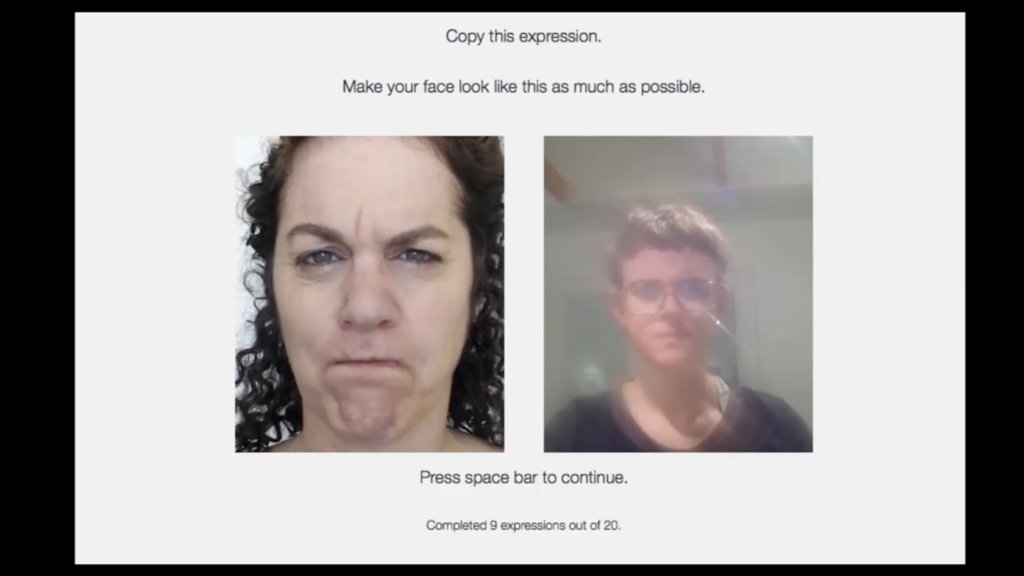

This of course brought back to me that my during and after my undergrad I was primarily employed through Mechanical Turk. This is me in 2013, a much younger version of myself, training a facial recognition database for roughly four dollars an hour. I did not really understand what I was doing. I don’t think I really understood the ways in which those types of structures were immediately bundled into harmful surveillance systems. I was also doing lots of like, medical research and was like oh yeah, it’s like a psychological study. But over time of course it’s become clear that what I was doing was training the same facial recognition systems that have come back to police bodies like mine and more vulnerable than mine. That even beyond my work, my body has been weaponized and recycled into a dataset that has come back to people I care about.

Could I talk a little more about the watching process of Moments in Time. It took about three months. About three months, twelve hours a day. And I… It was a truly dehumanizing experience. I like fully back to normal at this point, but I… I hope I never do anything like that again.

So both of those experiences, that feeling of making Lacework and then of recognizing my own history in sort of similar datasets to the ones I was working with went into Shell Song, a project at Open Data Institute, which is an interactive audio narrative game about corporate deepfake technologies and the datasets that go into their construction. It weaves together vocal training materials, and open source audio samples, and speculative fiction into a branching narrative structure that talks about like what voices are worth, who can own a human sound, how it feels to come face to face with the ghost of your body that may yet come to outlive you. And this is because you know, my own voice is also in those datasets, too, a voice that at the time it was recorded I used a different name, I used different pronouns, and now returns back to like, misgender my trans body in digital space.

So where do you go from here? For me, I think there was only one path forward, and that was through toolmaking and through organizing. This is Image Scrubber a tool for anonymizing photographs taken at protests, both through removing EXIF data and allowing various ways to paint over identifying features of people at protests.

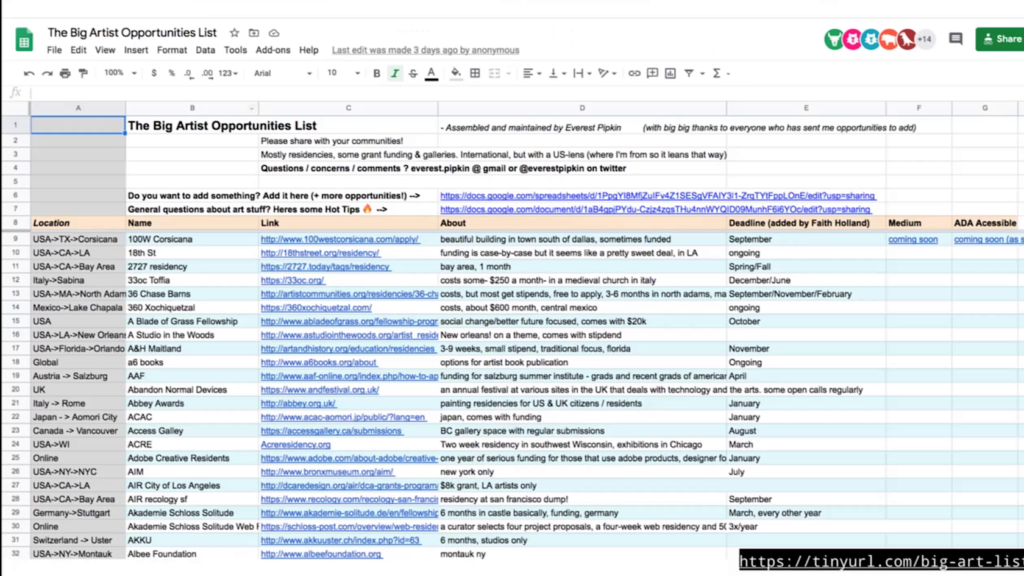

This is The Big Artist Opportunities List, many many many excellent opportunities in spreadsheet format, very easy to sort through; a kind of rude little “about” section from me for each one.

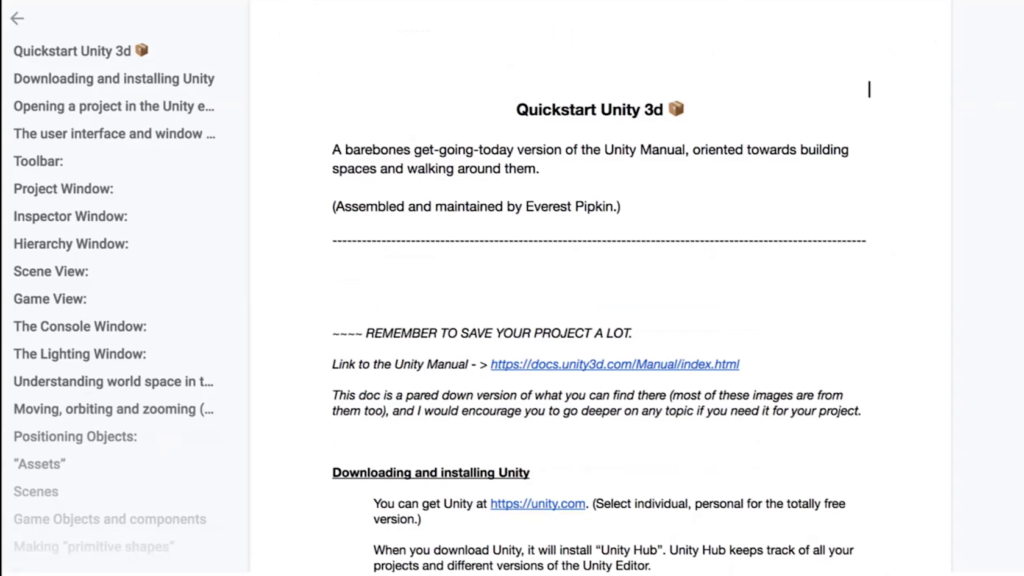

This is this Quickstart Unity 3D, only the essential parts.

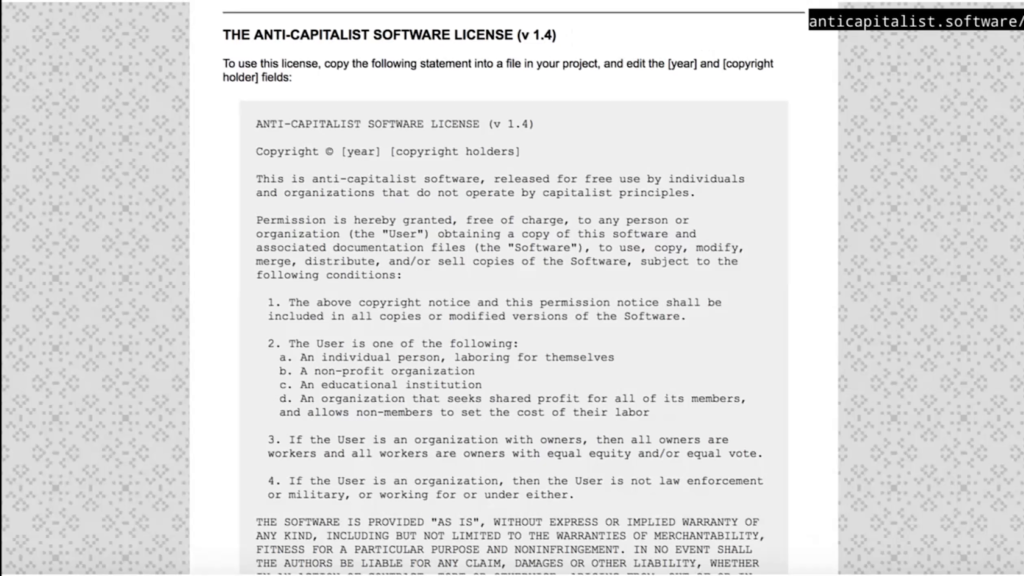

This is the Anti-Capitalist Software License, a collaborative project with Ramsey Nasser, which it does exactly what it says. It’s not an open source license because it does restrict usage, but it says that it can only be used by individuals, a nonprofit organization, an educational institution, or essentially a cooperative.

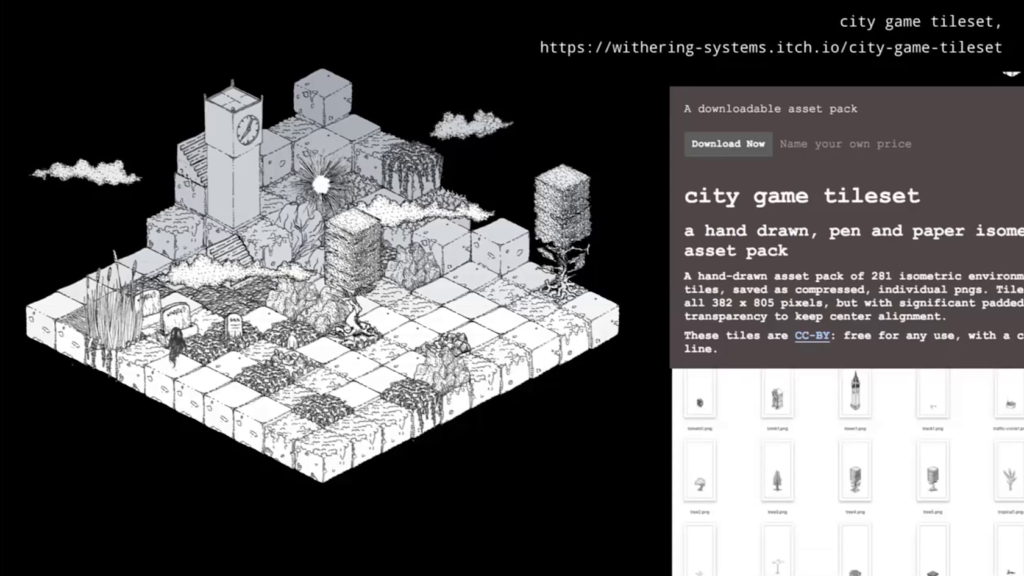

This is the city game tileset with withering systems. It’s a hand-drawn kind of paper isometric asset pack, free to use in your projects. Please use it.

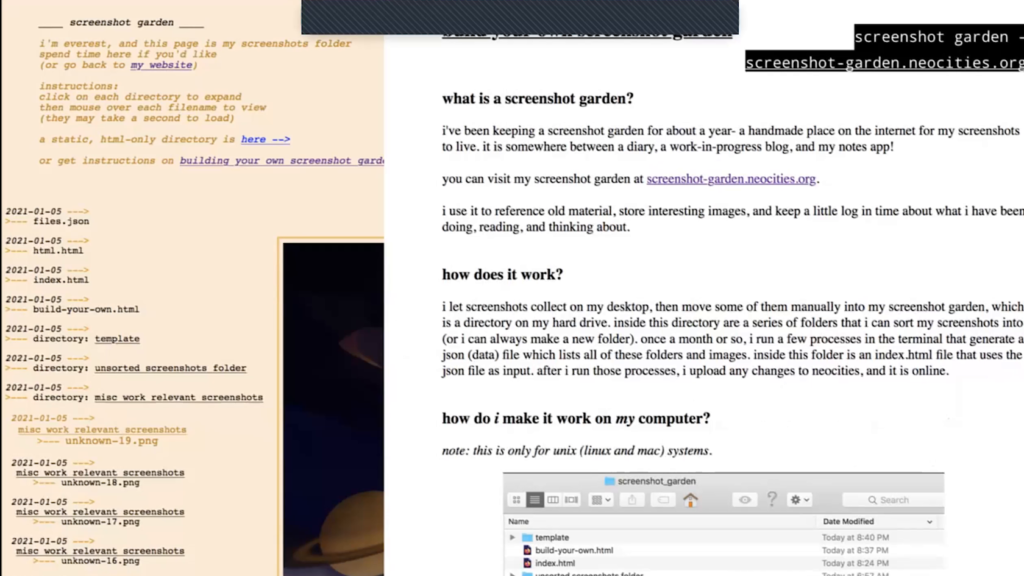

screenshot garden, a personal diary kind of replicating the internal folder structure as well as a how-to. And a little piece of code you can kind of copy and build your own in.

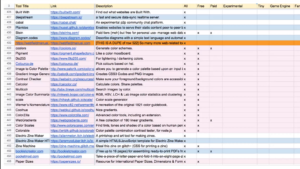

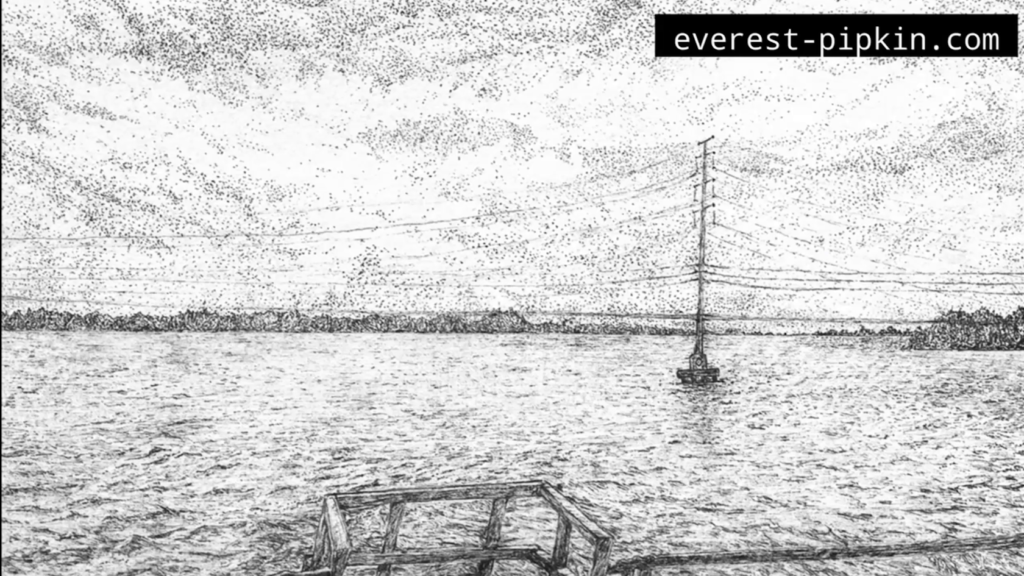

And what I worked on for this residency, which was the Open source, experimental, and tiny tools roundup, something that I’ve been working on for a long time now but that I went through over the last couple of months, tagged all now eight hundred-plus tools out for a variety of features. You know, whether they’re free, experimental, tiny, a game engine, a fantasy console. And built this kind of interface for sort of sorting through them, for moving them them to finding tools that allow you to engage in non-corporate, non-walled-garden, joyful digital creation.

And in a nice circle, this is also hosted on Neocities, the site that I look back on and on which I have made my kind of first painting-like forays into net art. And it’s all hand-written in HTML, based on a tool that’s also on the list which is named Leafy, all running on the front, readable and usable for the sake of View Source, copying, editing, learning a little bit about it, changing things, and making your own pages and places on the Internet to live and thrive in that embody those principles.

So all of this is a touchstone for me going forward. [Learning to live?] with maintenance, not of the things I’ve made but of the things that others use.

That’s it for me. Thanks.

Golan Levin: Everest, thank you so much for that wonderful presentation. We are basically at time but I’d like to maybe ask one brief question before we move to our next speaker. The question came from the chat here in the Zoom. How you would describe the relation between your traditional artistic practice, because you do a lot of drawings, and your computational practice.

Pipkin: Yeah. That’s a common question. In some ways they are separate practices. And some things are just better as a drawing or like, work better on a piece of paper than they would be in digital space and vice versa. But I also am often thinking about paper as a storage medium, paper as a really excellent piece of technology that endures, that doesn’t require consistent maintenance. I mean, you have to upkeep the piece paper, kind of, but not in the way that you have to like, keep a computer powered to function, right. You draw on it and it’s there, and it has such a depth of information storage, of hand, of capacity. It says so much about the person that drew that thing or wrote that thing on it. The pen they used, where that paper was made, the tree that it came from.

vlc-00_29_23-2021–05-24–01h57m49s503

Like all of that is held in you know, this thing. And it’s often a touchstone, right, when I’m thinking about technologies and tools. If they can be more like paper, if they can be as simple and as useful as a piece of technology like that. So…yeah. You know…it’s always in the back of my brain.

Levin: Thank you very much, Everest Pipkin.