Christine Lagarde: I wanted to start off this morning using an American poet and novelist, Langston Hughes. And I quote him to have said, “What happens to a dream deferred?” It is a question now facing millions all over the world, especially young people. Why? Because of poverty. Because of excessive inequality. And that is what I want to discuss this morning.

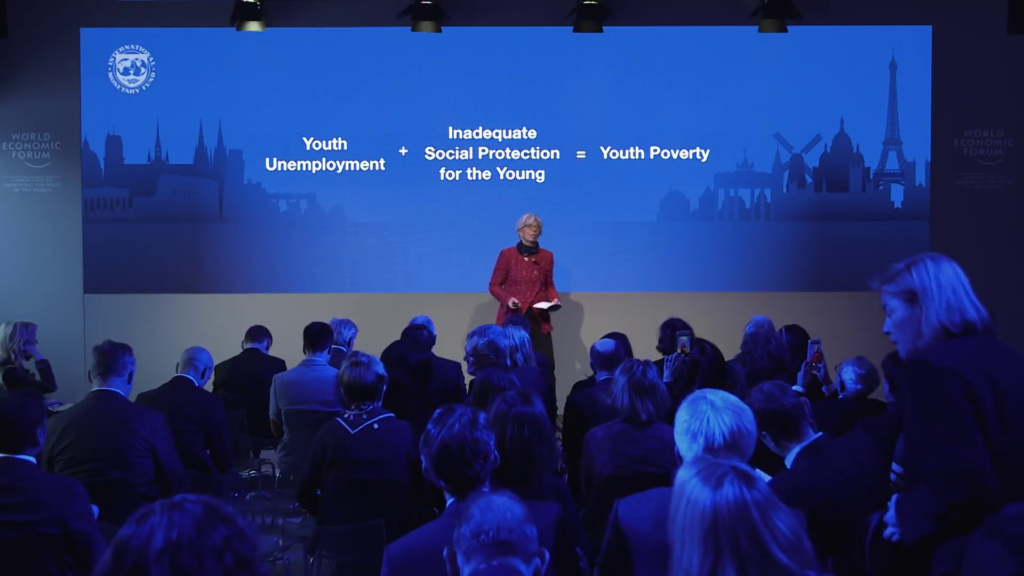

It’s a troubling equation, the impact of unemployment on the young, and the long-term consequences of inadequate social protection. But we will also explore ideas that can actually help fix the problem, deal with the issues, try to reduce poverty (one of the SDG goals), and reduce inequality for the next generation.

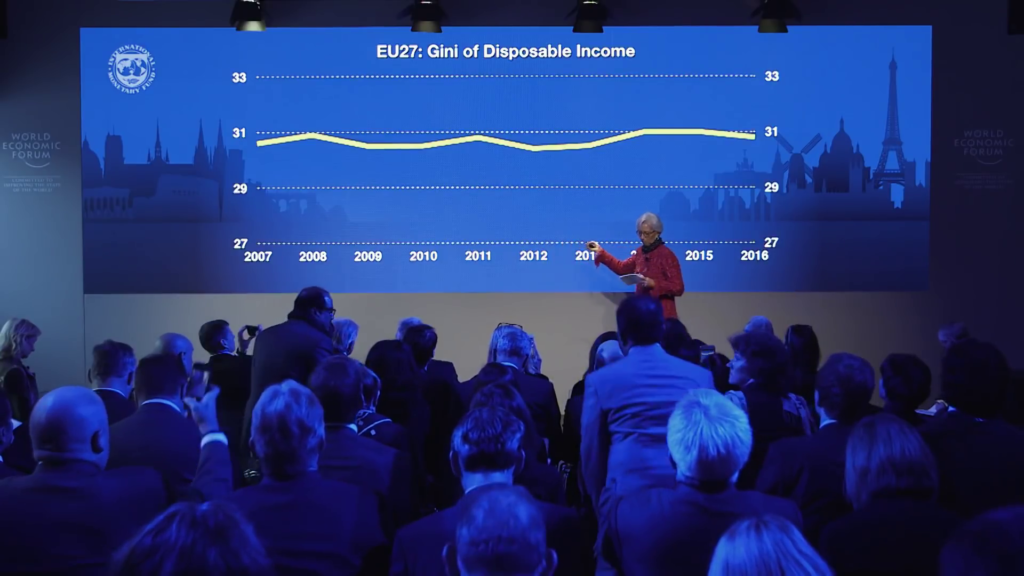

When it comes to inequality, one measure we look at, which is challenged, is the Gini coefficient. It captures the distribution of wealth. And by these measures, the advanced economies seem to be doing comparatively well. But what is behind those numbers? Let’s just concentrate on the European Union.

Why did she pick the European Union? Ah. It is certainly not the only region where young people are facing headwinds. But, we have taken advantage of what is available, and the data collected on age groups in Europe over the last decade is helping us shine a spotlight on this particular problem.

As you can see, average inequality has remained broadly stable. Here you go. And all of that since 2007. And this is in large part thanks to some social safety nets and distribution mechanisms that exist in Europe and not in other advanced economies, for that matter. And it’s an important achievement that has helped millions of people. And it has strengthened Europe’s position on inequality compared with other advanced economies.

But this top line that you see here actually hides an underlying threat to European youth. The reality is that the gap across generations in Europe has widened significantly. Working-age populations and especially Europe’s youth are falling behind. And if policymakers fail to act, this generation may actually not be able to recover.

Now, what has driven inequality across generations in Europe? There are many dimensions. Many, including wealth, including gender discrimination. But I want to take a closer look at income.

Income declined for young people after 2007. Due to what? Predominantly unemployment. But they have since generally recovered. For those who are 65 and older, incomes have increased since the crisis. Why is that? Because pensions were better protected. Youth in Europe have amassed the highest debt relative to their assets of any age group. That means that many young people are going to be vulnerable to the next financial shocks and are putting off investing in their future. In short, those dreams deferred that we were talking? They’ve put them on hold.

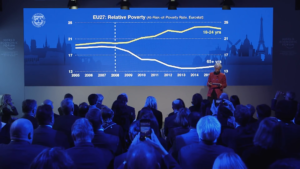

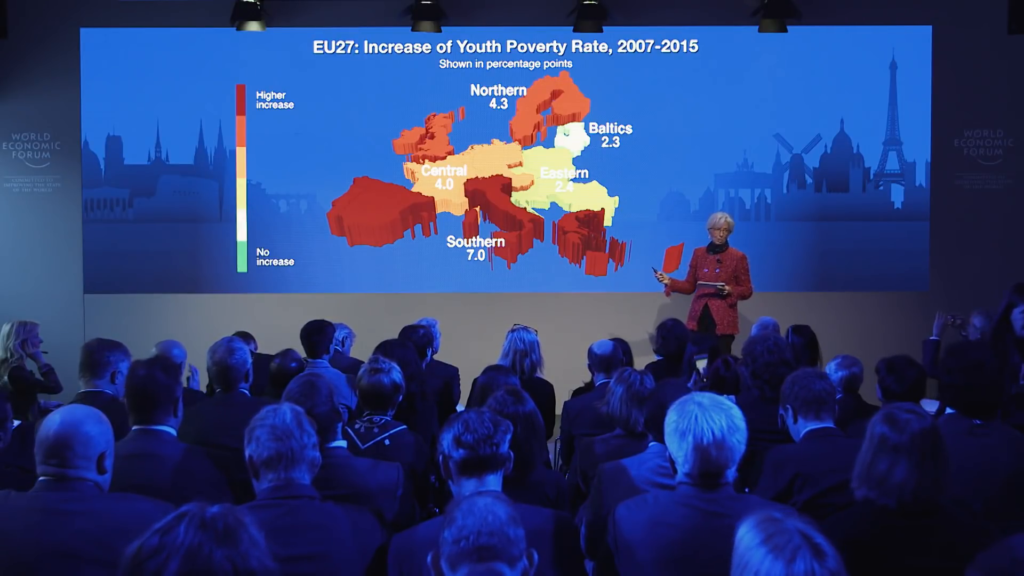

But incomes are only part of the story. Poverty is the other side of it. Before the global financial crisis, the relative poverty of the 18–24, and the older (that is 65 and over), was similar. Since the crisis, the gap has massively developed. Look. The reality is that one in four young people in Europe now live below the relative poverty line. Their incomes are below 60% of the median. Now you might say. “Sure, that problem exists somewhere. But not in my backyard.” Is it really happening across the continent? Well, it is.

Look at that. Now clear, some regions in Europe are experiencing more youth poverty than others. We can see the different rates between the regions. But everywhere, we have seen an increase. That means that young people in every region are indeed struggling.

How did we get here? Recessions and recoveries do not impact young people the same way as older people. Limited skills and experience often make it harder for young people to find work. And in Europe, unemployment of course rose during the crisis of working-age populations. But youth unemployment started high and spiked to what percentage? [inaudible response from audience member] Twenty-four percent. Correct. Twenty-four percent in 2013. He’s an IMF advisor, actually. So, 24% in 2013. Today, that’s improved a bit. Nearly one in five young people in Europe, though—one in five—cannot find work.

And we know that there is a connection between unemployment and inequality. If anything it’s probably the first big inequality. Lost wages, lost savings, can be extremely difficult to recover later in life.

For those young people who are still looking for work, the problem does not even end when they find a job. Why is that? Because what has happened is that they’ve had long periods of unemployment. You know, the forever stage, the forever internship, the non-remunerated experience. Well, that can lead to scarring. Scars that are left with them. And it means ultimately a lower probability of employment and life-long depressed wages. Instead of dreams deferred, instead of dreams on hold, we’re talking maybe about dreams buried.

But it’s not just unemployment that has led us to that point. Underemployment and temporary contracts, as I said, became prevalent during the crisis. The rise of the so-called “gig economy” exacerbated the problem and further decreased job stability, particularly for the young people. And unfortunately the social safety net that exists in most European countries was insufficient to help the young who lost their job or could only find those part-time jobs.

So following the crisis, non-pensioned social benefits were often curtailed, not indexed on inflation, and sometimes narrowly targeted. This limited effectiveness of these programs for the young people.

Now let us be clear. Fiscal programs such as pensions and social securities have helped millions before and after the crisis. And the point of our study is not to say it’s them versus us. And certainly not to undermine what has been made available to the senior citizens. And we need to continue to protect them. But we also need policies that look out for the young and reflect the changing nature of work. In fact, some countries are actually doing it and making progress.

Now, of course you would expect me to quote Germany. And I do. Long-standing apprenticeship, training programs, have helped Germany’s young stay in the workplace. I know there are very recent numbers that are a little bit worrying but in the main, and certainly over the time of the crisis it’s been very helpful. And Germany’s flexible employment rules allowed young people to keep their jobs during and after the crisis. Today, Germany’s youth have the lowest unemployment rate of any European country.

Now, is it just all about Germany? No. Mr. Prime Minister; Portugal. And I’m not doing that because you’re in the room. Policies were implemented to exempt first-time jobholders from paying social security taxes for three years. It has helped. In France (the Prime Minister is not here but let’s mention France) labor taxes levied on employees are being reduced, while a tax on total household income is being increased. This should help working-age populations and rebalance some of the tax burden across generations.

Now, we at the IMF are also looking at it. Our work highlights policies that can help the prospects for young people around the world. In fact we’re launching a new paper today that focuses on youth inequality and poverty in Europe. And based on our analysis, I’d like to just mention a few policies that we believe could have a positive impact for young people.

One, look at the labor market. To create jobs and incentivize work, policymakers can reduce social security contributions and taxes on low-wage workers. There is discussion amongst economists, some will say no no no, you have to go beyond that. We believe that at the low-wage level it is the most efficient. To help improve future job prospects, governments can invest—should invest—in education and training. This will allow young people to close the skill gap that we have observed.

Second, countries can make government spending on social protection more effective. How? Part of the answer is to actually adapt social spending, especially unemployment and non-pension benefits, to ensure that young people are better protected.

Third, taxation. Since 1970, there has been a decline in wealth tax. And in some countries, not all, but in some countries, more progressive tax systems and wealth tax, including inheritance taxes, could help fund much-needed social programs for younger citizens.

And as I said, in the end it is not one age group against the other. Building an economy that works for young people creates a stronger foundation for everyone. Because after all, the young people are going to be the contributors to the pension schemes that are being honored at the moment. And reducing inequality goes hand in hand with creating sustained growth and rebuilding trust within society. Now, this is easy to say, and none of this is easy to do. But each policy needs to adapt to the needs of countries, recognize political realities, and stay within budget.

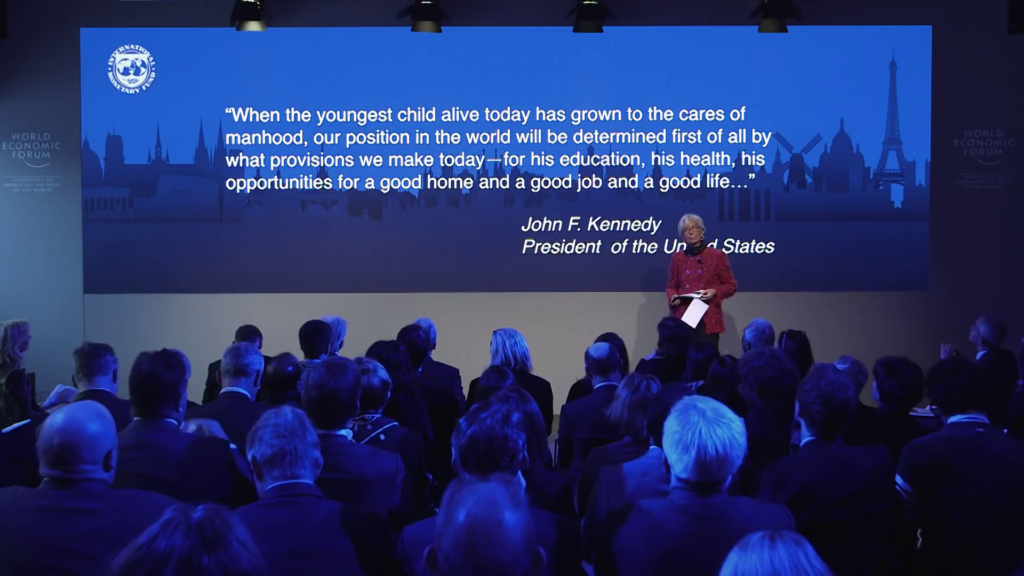

So, you may have heard me say that it’s when the sun is shining that you need to fix the roof and that now it’s time to act—yes it is. Now, why is that? Because of the recovery that is accelerating. Because of growth that is really going to facilitate that. Globally, but in Europe in particular, where it had been long in the waiting. As I said, time to repair the roof when the sun is shining. I’m borrowing from John Fitzgerald Kennedy from his State of the Union Address in 1962. Not all of you might know that he actually focused his speech and opened his speech focusing on the next generation.

In this moment of global growth and European recovery we have an opportunity to do the difficult things which might otherwise go undone. In Europe, one of the ways to fix the roof is by designing the policies that will help the next generation. Help them reach their dream. We can help. There are tools. There are policies. There are best-case stories. We can just make sure that we don’t have to ask the question “what happens to a dream deferred?” Thank you very much.