When I was seventeen, I was diagnosed with Crohn’s Disease, which is an auto-immune disease and it’s a permanent infection in my gut and bowel. It really sucked, and I was in hospital and I almost died. When I came out of hospital, I was taking about sixteen tablets a day, and if you include all the painkillers and supplements I was taking, I was taking about twenty-four or twenty-five tablets a day. One operation and about a decade later, I’m still taking tablets. I’m not sure if you can see those, but these are the tablets I take every single morning, and I take two more of those big white ones in the evening. And the 5p is there for size reference.

And it’s because I take these tablets every day, I have to think about everything else that relates to those. So, do I have enough, I’m going on holiday, do I need to go get some more tablets, run around and get a repeat prescription. I’m going out tonight, can I get into the pub if they search me if I’ve got my tablets on me. I’m staying at someone’s house, is my cache of meds that I’ve got split all over different people’s houses in London, are they there as well? And because I have to think about this twice a day, not dying has always been fairly high up my list of mental priorities.

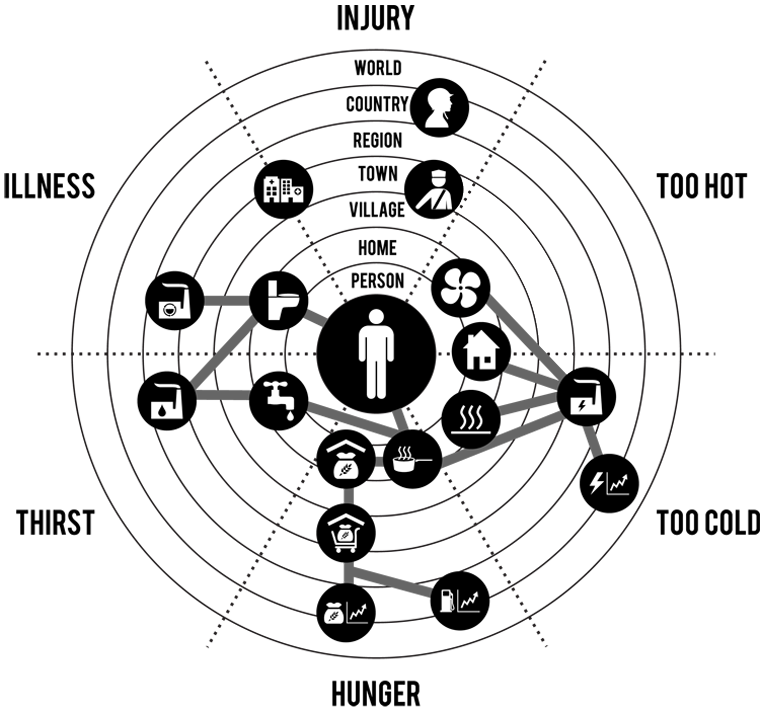

So in 2011 I came across this talk called Infrastructure for Anarchists, and its sister talk Avoiding Capitalism for the Next Four Billion, which was by Vinay Gupta at the 2009 Temporary School of Thought. In that talk he talked about Simple Critical Infrastructure Maps, or SCIM. You can find the documents, resources, and all the various graphics and images at resiliencemaps.org if you want to check them out.

These maps were originally designed to allow someone to orientate themselves around the infrastructure and they exist inside in the event of a crisis. The way it does this is by plotting the six ways to die: too hot, too cold, illness, injury, hunger, and thirst. If you’re not dying of one of these six things, then you’re going to be dying of old age. Then what it goes on to do is that it puts the individual at the center of the map and then concentrically moving out from the individual, we move through those spaces up to the world level. And then it maps infrastructure, or the means of not dying, against those concerns. So if you can see on the graphic, see there’s cooking. Everybody needs to eat. That’s relating to the electricity grids, which is related to the international energy markets. The cooking is also related to how and where you store your food, and that’s related to where you get your food from, the derivative markets, and the fuel markets. You also need fresh water to eat and cook, so that’s related to your source of fresh water, and the municipal water system. You’ve got waste and then the wider sanitation system.

These maps were originally designed to allow someone to orientate themselves around the infrastructure and they exist inside in the event of a crisis. The way it does this is by plotting the six ways to die: too hot, too cold, illness, injury, hunger, and thirst. If you’re not dying of one of these six things, then you’re going to be dying of old age. Then what it goes on to do is that it puts the individual at the center of the map and then concentrically moving out from the individual, we move through those spaces up to the world level. And then it maps infrastructure, or the means of not dying, against those concerns. So if you can see on the graphic, see there’s cooking. Everybody needs to eat. That’s relating to the electricity grids, which is related to the international energy markets. The cooking is also related to how and where you store your food, and that’s related to where you get your food from, the derivative markets, and the fuel markets. You also need fresh water to eat and cook, so that’s related to your source of fresh water, and the municipal water system. You’ve got waste and then the wider sanitation system.

So this in a very simple sense is the Stack, or the infrastructure mapped around us against the means of not dying. It’s this infrastructure that is unseen, because it is infra-structure, it is under the structure. And when you start thinking about this massive web of technologies that keep you alive, the only interfaces we have on a day-to-day basis are tap, turn, flush. Everything else is hidden and unseen. Paul [Graham Raven], who’s not here yet, who’s speaking later, he calls this “problematizing the tap from the other side of the wall.”

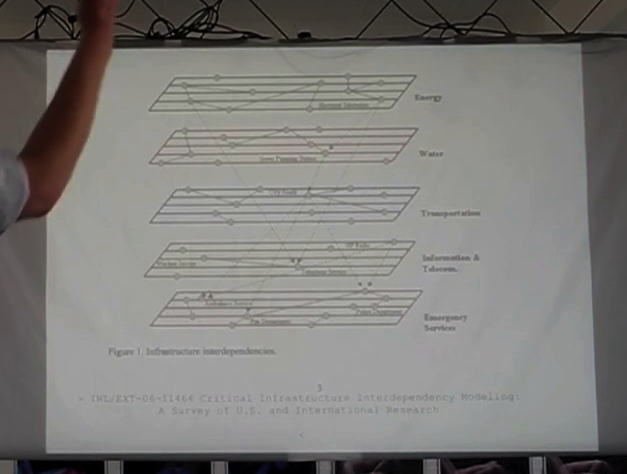

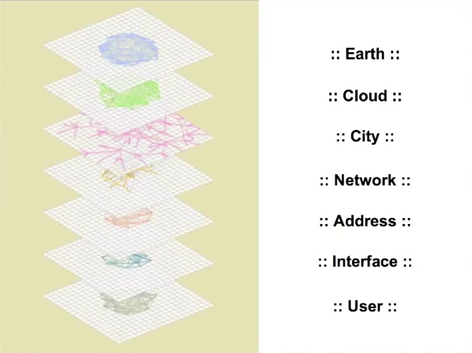

This is an infrastructure dependencies map, and you can see this is the stack of technologies, the various discrete levels of infrastructure which are vertically aligned and yet interdependent on each other. This in its crudest diagram is an example of the Stack, with its different levels of verticals. Benjamin Bratton, who’s writing a book called The Stack primarily talking about the Cloud, gives us some conceptual language around the different parts of the stack as you move up and down these verticals. I find them quite useful in conceptualizing these things.

This is an infrastructure dependencies map, and you can see this is the stack of technologies, the various discrete levels of infrastructure which are vertically aligned and yet interdependent on each other. This in its crudest diagram is an example of the Stack, with its different levels of verticals. Benjamin Bratton, who’s writing a book called The Stack primarily talking about the Cloud, gives us some conceptual language around the different parts of the stack as you move up and down these verticals. I find them quite useful in conceptualizing these things.

Then there’s the SCIM maps, which the more I’ve thought about them, it’s almost as if the Stack, the vertically-aligned infrastructures have been turned on their sides and now you’re sort of peering down this cone of infrastructures out from the world level, down to the individual level, and seeing interdependencies which they have.

I don’t know if it’s because I’m a [sci-fi?] nerd or because I reject the idea that the history of civilization is the history of great men, but I’ve always believed that the history of technology is the history of civilization. So time is also a factor when we’re thinking about the stack. Jo Guldi, who’s the author of a book called Roads to Power, Britain Invents the Infrastructure State, talks about how the reason that the English government got involved in road-building during the Enlightenment was essentially to open up trade between Wales and Scotland because their premise or their thought was that if we open up trade between these regions, then the Welsh and the Scots will stop having barneys with the English.

Municipal infrastructures like gas, sewers, and water, these are the 19th century infrastructures, which are very Victorian in their thinking. They’re very command and control. You build a big water plant on the outside of town and then you connect everyone to it, but all of the business is secured in one place. And then of course we can go up through the stack. We have the invention of the electricity grid, communications, and then the Internet, and then even satellites.

One of the problems with thinking critically about technology is that you could pejoratively be branded a Luddite. But that’s okay because one of the things the Luddites understood was that certain technologies internalize certain ideologies, which is why when they went into the factories they only smashed certain types of machines and not all of them.

So if this is true, then the roads have this implicit or in-built ideology of capitalism. The municipal infrastructure has the in-built ideology of Victorian command and control structures. And then if we also think about the Internet and the horizontalism of the infrastructure and how that ideology has kind of either affected us or has been imbued within the technology.

In this sense the stack, not only is it vertical aligned but it also leans through history. And what that means is the internal biases of these levels of the stack, they carry with us through time. So until those levels of infrastructure are gone or have been replaced, we’re still subject to their invisible biases.

So who controls the stack? It’s a bit more of a pertinent or public question and it’s in the media in light of the PRISM and NSA scandals, with their access to the infrastructure level of the Internet. We can also think about Israel turning off the water to Gaza in 2005. They turned the entire water grid off just long enough for all of the plants to die in the greenhouses, and then they turned it back on again, and they’ve done it a number of times since.

For me when I think about it, these are my tablets in this bag here. This is part of my personal infrastructure, and the white ones are manufactured under license by Ferring in Denmark, distributed within the EU, and the component part of them which is mesalazine is under eleven international patents, nine of them worldwide. Do I have a moral right to the access to these tablets, and if I could, do I have the right to make my own? So one of the things for me is to see the invisible, the invisible biases imbued in these things, understand the infrastructure around them, and then try and do something about it. And that for me is Stacktivism.

Thanks very much.