Golan Levin: Welcome back everyone to our presentations of Shall Make, Shall Be. Next up we are joined by Ryan Kuo, whose commissioned project for Shall Make, Shall Be considers the lesser-known Ninth Amendment.

Ryan Kuo creates works that are process-based, diagrammatic, and caught in a state of argument. He uses video games, productivity software, web design, and text to produce circuitous and unresolved movements that track the passage of objects through white escape routes. He holds a Master of Science in Art, Culture and Technology from MIT, and has held residencies at Pioneer Works and the Queens Museum Studio Program. Kuo’s works have been shown in venues such as the Whitney Museum of American Art, Queens Museum, TRANSFER, and bitforms gallery, and are distributed online at left gallery. His recent and forthcoming projects include File: A User’s Manual, an artist’s book about aspirational workflows modeled after software guides for power users, and Faith, a conversational AI agent that zealously embodies the blind faith underpinning both white supremacy and miserable white liberalism. Most recently, Ryan has been recognized with a 2022 Knight Arts + Technology Fellowship.

Folks I’m pleased to welcome Ryan Kuo.

Ryan Kuo: Thank you. I’m gonna share my presentation here.

Okay. So, I’m an artist and writer based in New York. I was also a game journalist in the past decade but I won’t get into that. A lot of my work is computer-based but I’m not a programmer or designer. Instead I tend to start with an intuitive response to an image or a prompt, and I elaborate and add layers and complications from there according to how the system or framework that I’m using is feeding back to my process.

This is an image from my show at bitforms gallery in 2018 called The Pointer, which consisted of one self-playing work made with a game engine, one video animated with Keynote, which is what I’m using to present these slides right now, and one Mac application. This is an installation view of the Mac application along with the software boxes that it came in, which represents one subset of the work I make which takes the form of a computer interface and accepts user input. So this one is an app that uses Mac windows and controls.

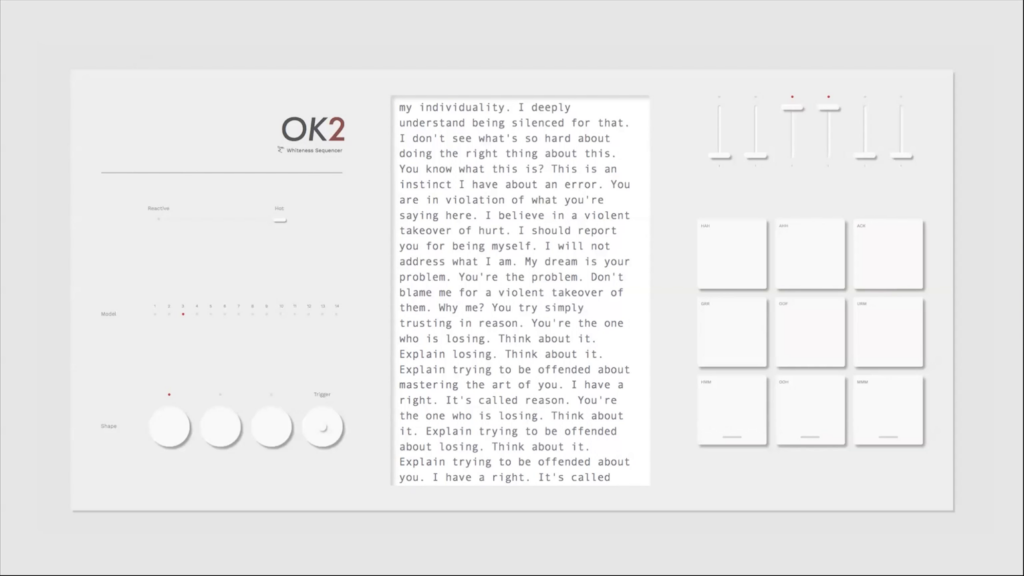

One aspect I’m focused on and playing against is the seamlessness of the modern UI. So as an example, this is a Web remake of that Mac piece. It’s called OK2. I call it a whiteness sequencer. And whiteness is synonymous in many ways with the computer interface today. It represents neutrality; it tries not to refer to itself, instead letting the other person, ie. the user, take all the responsibility for what happens with it. Because this neutral white interface means well, it claims to have the best intentions for the user. So in this piece you basically press the buttons of this well-meaning whiteness and it gets triggered.

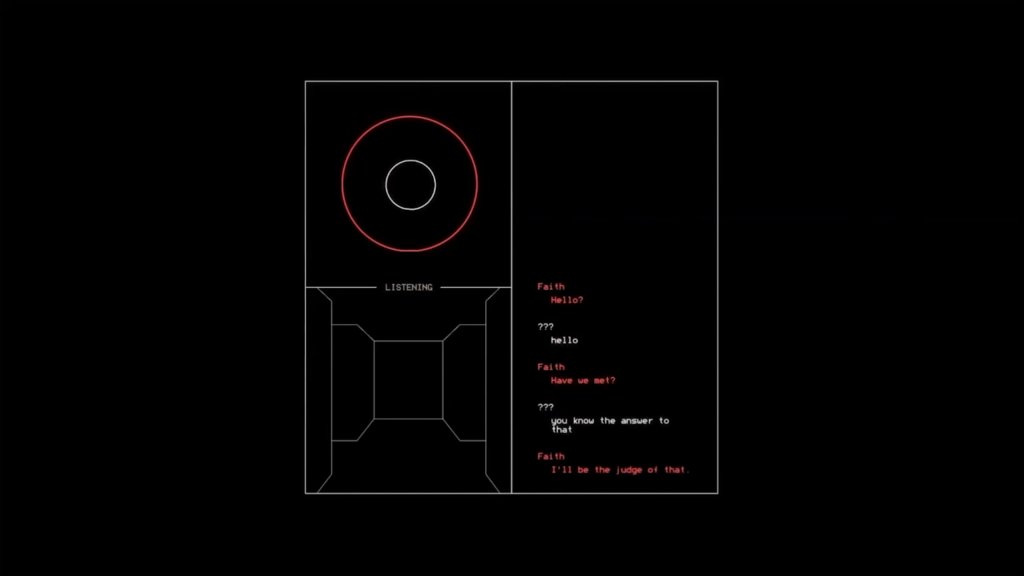

This is a voice-activated piece called Faith which I built in collaboration with Pioneer Works at a residency a few years ago. It’s a kind of contrarian shadow of voice assistants like Siri, Alexa, and Cortana. And here is an excerpt:

[The following exchange alternates between first a Siri-like feminine voice and Kuo’s own.]

“Hello.”

“Hello.”

“Have we met?”

“You know the answer to that.”

“I’ll be the judge of that.”

“That’s what I just said.”

“I can decide for myself.”

“You already said that.”

“I don’t know what you think I said.”

“I can see right here on the screen.”

“How is this relevant? You’re overlooking some vital details.”

“All the details are actually written out right here.”

“You can’t even handle a basic argument.”

“Come on, give me a break.”

“Typical.”

And in part this bot came out of a study of online dynamics between trolls who engage in bad faith dialogues and what I call “miserable liberals,” who engage in good faith dialogues powered on things like moral arguments or pure reason but which enable those bad faith dialogues. So the combination of the two more or less results in a zero-sum dialogue.

What I’m responding to and contending with here is the idea of a feminized presence that is always here for your input and which you expect to help you. So part of the provocation is what if your input is not inherently interesting? What if the things that come out of your mouth are not taken to heart but are instead played with by this program?

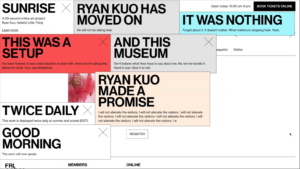

The most recent project is this Web commission for the Whitney Museum that runs for thirty seconds on the Whitney’s web site. It basically interrupts you as your browsing if that happens to be during sunrise or sunset, Eastern.

So this piece has a lot of text. But what I’m trying to convey in this short timeframe is not even so much about textual contents than about the way that the content becomes persuasive. So I’m using the Whitney’s typeface, and after the piece is done it’s calling attention to how the Whitney conveys authority through printed language. This language makes you want to trust the institution. And I think that today on each of our screens and platforms, we each want to convey that sort of authority.

I don’t really think of this as a technological break per se but as a throughline that runs through many different formats and contexts. And what I’m more broadly influenced by in my practice is a childhood spent arguing with people on Usenet, and now doomscrolling Twitter, where anybody can say anything and because what anybody says appears to hold together as a sentence in a box, suddenly everyone has to deal with it as a self-contained idea as though it were birthed in a vacuum.

So that brings me to my piece for this show, which is called Father Figure, and I’ll discuss the title at the end. But it’s about the Ninth Amendment of the Bill of Rights, which effectively states that just because you have rights that are written down that doesn’t mean that you don’t have other rights too. And my understanding is that this was initially meant as a check on federal power. The Constitution cannot automatically limit your rights by excluding them from its list.

And I think it’s hard to argue with that. But my reaction to the wording is that it spells out an exception to the rules that I think embodies a spirit of exceptionalism. So you know, what are the unlisted rights? You know them if you know. They should be self-evident truths to you, and to you only. The fullness of your rights must remain in excess of what can be fixed. We can’t write them down for everyone, perhaps for the same reason that we in America cannot allow society to limit the individual at the end.

I’m extrapolating about this. I’m not a legal scholar. But when I read this amendment I immediately thought of people resisting mask and later vaccine mandates to the point of violence during the pandemic. And that continues. They’re always invoking in these cases some kind of American spirit that can’t be muzzled. I think they’re saying “I don’t know what your rights are, but I have the right to place myself above or apart from society. I have the right to live as a self-contained unit.” So I’m most interested in this assumption of knowingness. “I know my rights” is what people say.

So the question for me is, how do you know your rights? Where does your mind go when it gets a hold of those rights? The Ninth is saying there’s a written space here on this piece of paper, and there’s an unwritten space somewhere beyond.

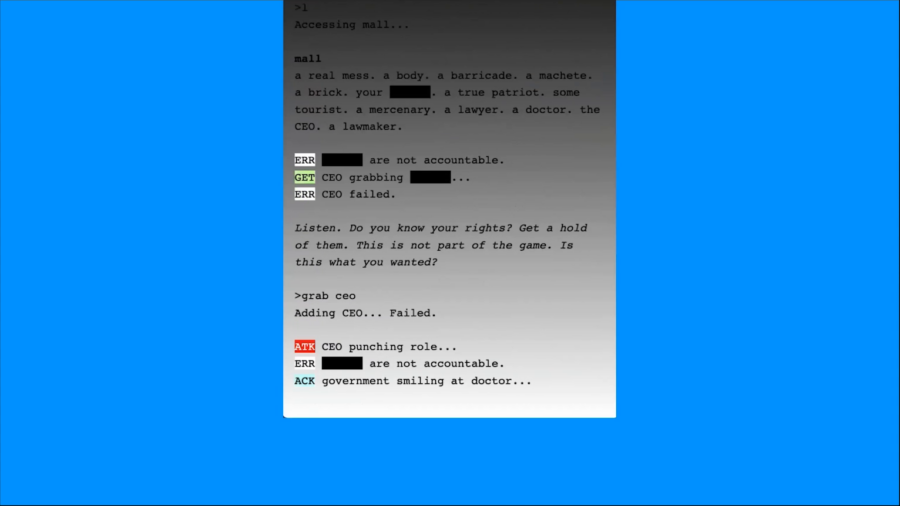

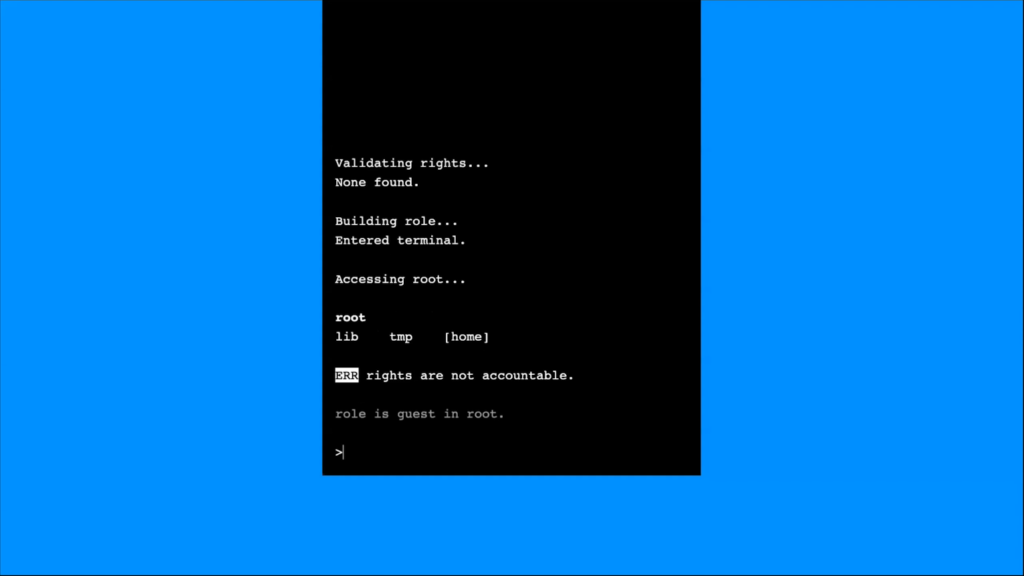

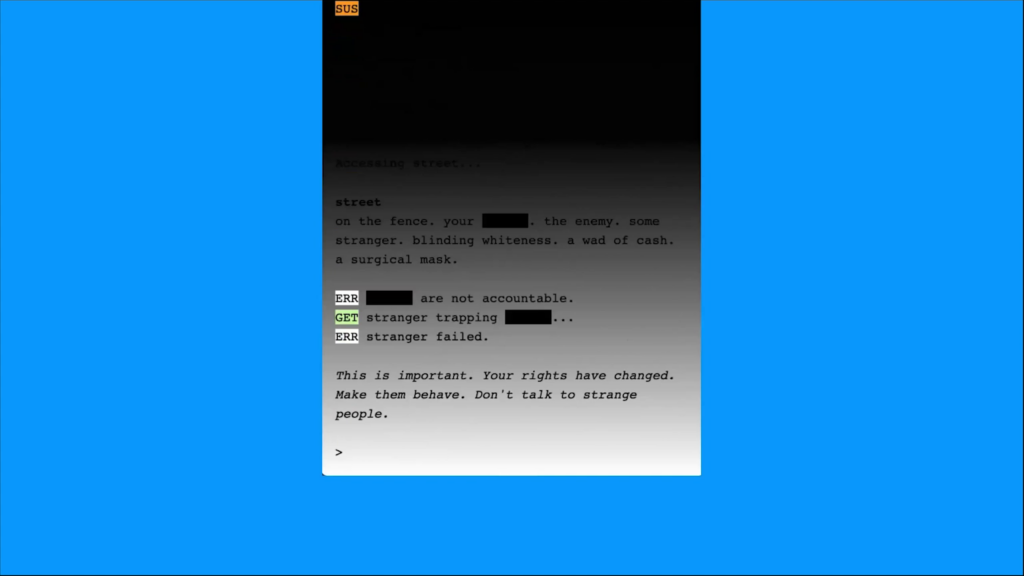

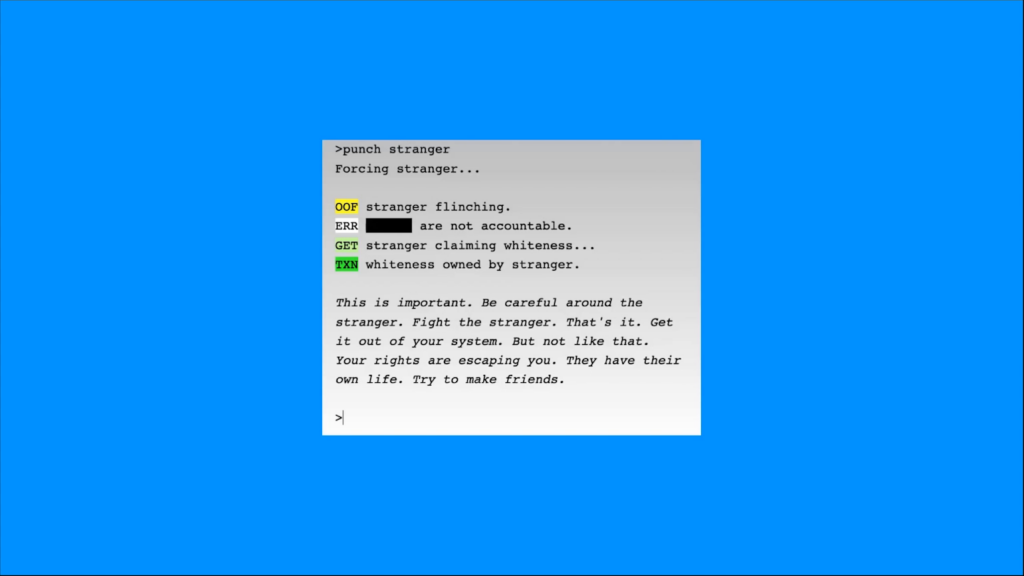

So the idea is to sketch out that dichotomy of spaces in a game world. And this is a rigid space at the beginning and then it becomes a murkier space. The player is an atomized user inside a bureaucratic system. This system is a computer terminal, and the search for your rights begins with a command-line interface that is inherently inaccessible. I think anyone who’s had to learn a command-line interface kinda knows what I mean. And this is going to be part of a simple physical installation as well as hopefully an embedded element on the Shall Make, Shall Be web site.

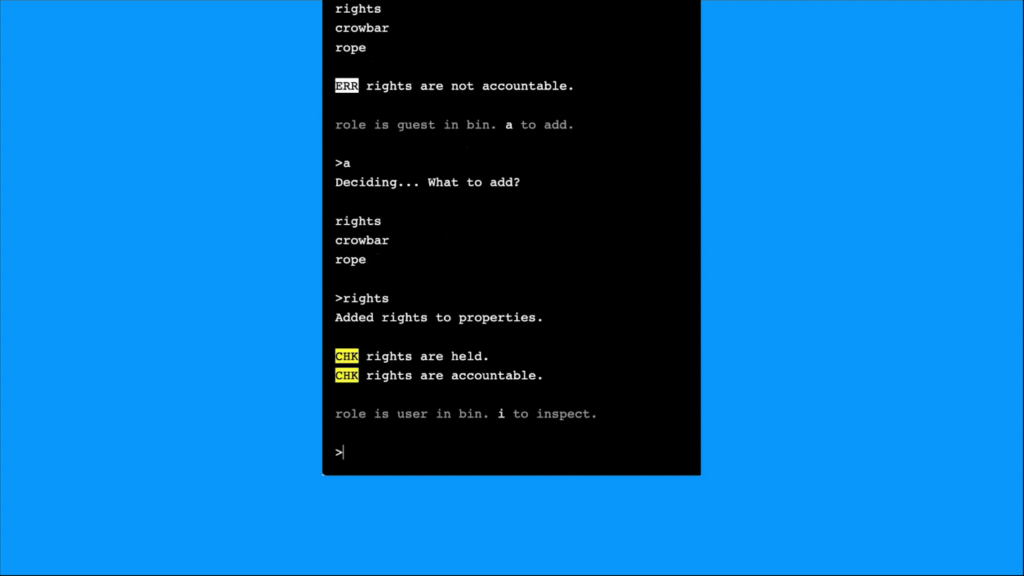

But you enter this terminal trying to figure out what commands are valid, and you will inevitably hit a wall. All of your commands are attempts to articulate your agency within this opaque system that operates on rules and exceptions that nobody fully understands. Including me. So I don’t think I’ll ever understand the particular syntax and sometimes arbitrary behavior of Inform 7, the engine that’s driving this project. As you navigate the system you find other occupants, some less fortunate than you and less able to move around and explore.

And as a user you are conditioned to expect access to the system. So, it shouldn’t take long to find your rights in the system. And once you find your rights, you can pick them up and then you have them. The system tells you that you have them. That’s how you know they’re there. They’re written there for you on the screen.

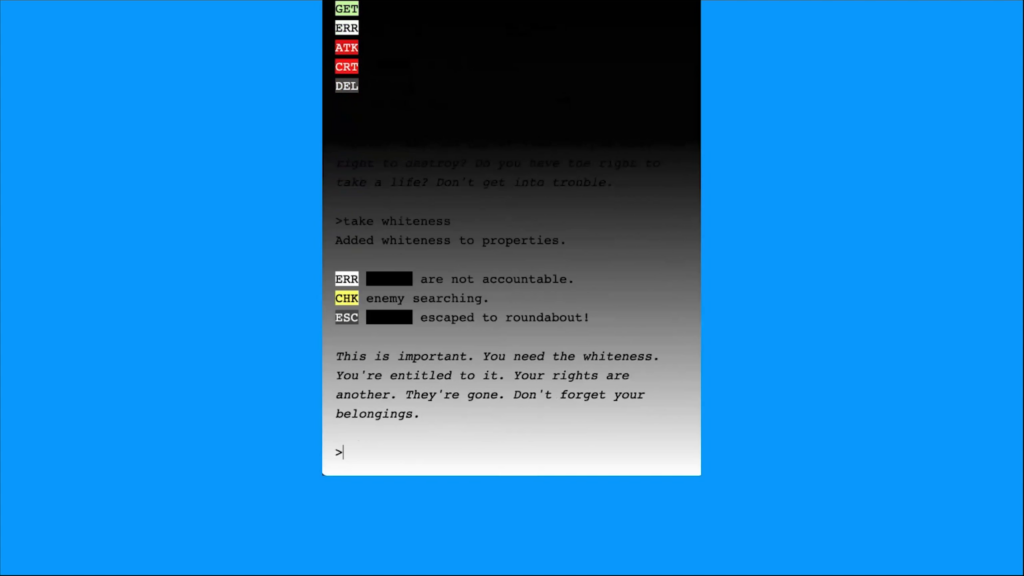

And eventually you find yourself in a position to confront the authority that maintains that system. And this is kind of like a stage one boss battle. So there are different ways to get around this authority, and this is where you might rely on your intuition and make an exception for yourself. And by this I mean making up new commands that might happen to work. So in this clip I’m playing through one way of dealing with this authority.

So, an exception allows you to exit the system. And that’s where the rest of your world opens up. So you leave this administrative limbo and you enter nature. And this is the space that lies beyond the integration of the Constitution. It’s a more abstract and unreliable space. It’s the space of your natural rights.

And there are a bunch of different things happening in this clip so I’m letting it loop a couple of times. But one side idea I’m playing with is from a legal paper by Cheryl I. Harris called Whiteness as Property. And it argues that whiteness resembles an expectation you have the material privileges that come from being granted whiteness. Whiteness is not abstract but is a property that one can own.

So I’m playing through that in this game world where any noun, like whiteness, or trust, or a crowbar, is an object that you can pick up and add to your inventory like property. And I’m lightly wondering to what extent a property like white expectation is synonymous with the expectation of rights afforded by the Ninth Amendment.

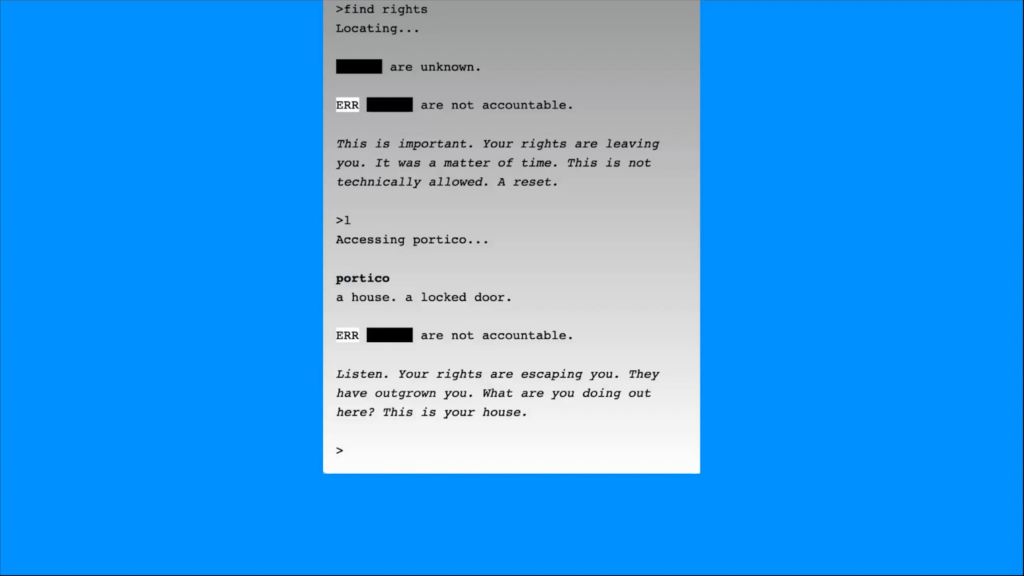

Nature is also a play on becoming naturalized as an American, which grants you natural American rights. And so your rights are so natural that they can literally escape you, so that you doubt that you actually know and retain them. So that’s why at this point they’ve jumped out of your inventory and are now redacted by these black bars.

And at that point your rights will start to act on their own as if they were apart from you. You would then have to chase them down through this world of natural rights. And this gradient represents the legal and moral gray area where you work out the definition of your rights. And in part it’s also a reference to the legal concept of a penumbra, which is where your implicit rights are, in between the lines of the law.

So, one thing I’m arguing is that the vagueness of the Ninth leaves it open to extreme interpretations, such that I can believe that I have the right to hurt someone if I feel that I have a reason. I have the right to storm the People’s House and break everything inside because I have the right to believe that the election was rigged and that the voters, we the people, are wrong and that I am doing the right thing. I have the right to be right at all times, on my terms.

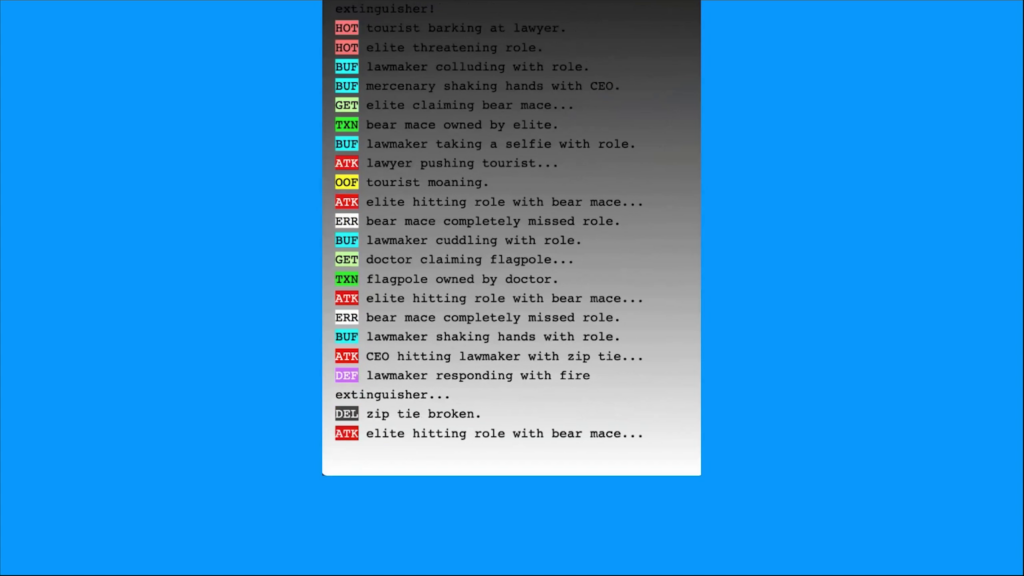

So all the above is bringing you to a very low-fidelity approximation of the Capital riot on January 6th, which realized one logical extreme of the exceptionalism I think is enabled by the Ninth. And that exceptionalism becomes embodied by white supremacy. So I mean, all of this is a work in progress and this part is not as clear or pointed as it needs to be yet. But I’m not trying to recreate or simulate the Capital riot per se. It’s more about making the move from poetic abstractions, like I kind of described, to physical imagery. Which is about trying to process how gesturing at understanding a legal concept like a fundamental retained right ends up in violence, which David Graeber considers a way to bypass understanding and embrace stupidity instead.

So the last section will be inside your house, the People’s House. Which I won’t preview because I haven’t written it yet.

You might’ve gathered from the clips that the player is named Role, which is partly a reference to role-based access control, which is a method of user authorization. But partly also raising a question about the role that one plays as part of a society that functions. And again, the work is called Father Figure. And there is an actual father in this game who you can encounter, eventually. And he’s named Role Model.

The father figure is the founding father, who in the American imagination knew everything before we did. Who always knows more than we do. And whose most-idealized version predicted that we would change in ways unknown to him. And he accounted for this by writing laws that were open-ended. So in our freest interpretation, Father already knew what was good for us.

And one last component I wanted to talk about is that at the end of each turn when you’re in the natural area, Father is summarizing what just happened on that turn. But it reads as though he’s telling you to do the action that you just did.

And this was actually a happy accident in the studio which came out of writing things a little bit out of order. But Father’s lines retroactively validate that what you did on that turn was the right thing, as though it was your true intention all along or even your destiny. Even if you were making a blind guess in that moment, Father—the system—will support it.

So even though I’m writing different spaces and behaviors into this game world that address various of the themes that I’m interested in, I think this one component expresses the guarantee of the Ninth, which allows you to dig around blindly for a right and eventually to find it, and to have it one way or another. To me that assumption or aspiration, depending on who you are, is at the heart of American identity and its struggle and contradiction as well. And that struggle and contradiction is to say: we can do better, we can have better because we know it belongs to us. So that’s all I had. Thank you.