Okay, reading the riots on Twitter. I just want to briefly say a few things for those of you who don’t know what happened in detail last summer in the United Kingdom. It started on the 4th of August when a man was shot in Tottenham. His name was Mark Duggan, and he was shot by the police. And he was shot under very suspect circumstances that were never really fully cleared up. And his family at the time really was looking for answers that they didn’t get from the police. So on the Saturday after his death, a number of family members and community members went to the police station in Tottenham to seek answers to what has happened.

And they didn’t get anywhere. Nobody would speak to them, and so they were there as a group of people from the community as well, and nobody would speak to them. No senior police officer addressed them. They left around nine o’clock, at which point the tension in the area was really mounting and sort of tipped over. The family went home and the tension really tipped over, and that’s really when the spark of the riots started with the burning of two police cars in Tottenham.

Leon Neal/AFP/Getty Images

This led to further widespread looting in the Tottenham area, and this is one of the images that you may remember if you followed this at all on the news. This certainly is one of the images that I vividly remember when I followed the news on Twitter and just had this awful feeling in my stomach, thinking this is just going to blow up beyond proportion, particularly to do with the circumstances of his death. And it did.

The next day in London, it spread. It spread to the North of London to Enfield initially, and then also to the South to Brixton, as well as other areas in the city. And the focus moved away slightly from clashes with the police and was now very much about looting and stealing certain items. You may remember that one of the stores in particular that was hit very heavily was Foot Locker. Foot Locker seems to be caught up in riots quite often, and we can think about the commodity and hyper desires people have for particular trainers. So Foot Locker was hit very heavily during the riots.

On the third day, the disorder spread to other parts of the United Kingdom, and London itself saw the worst 24 hours of civil unrest in its recent history, and 22 or the 32 boroughs in London were very negatively affected by rioting. And its worth taking a deep breath to imagine the scale of a city like London and the scale of 22 out of 32 boroughs being affected by this. On that third day, two people died as well, and the riots spread further across the United Kingdom to large population areas including Birmingham, Nottingham, and Leicester. So this is really spreading like wildfire on day three.

On day four, things both escalated further in the North of England, so rioting spread to Salford and Manchester where I live, but also because so much police was drafted in to London in particular, there were very few incidents in the capital on that fourth day. In Birmingham, however, one of the worst events within that very short four-day period took place when three young Muslim men who were protecting property were killed by a car, a person driving deliberately into that crowd. Those of you who followed this news on the international media or Twitter, will all remember the father of one of these young men who really stood out for his enormous strength of character for speaking against people retaliating the death of his son.

So what as going on? Why were people doing this? It spread like wildfire and nobody really had an answer, except a politician said well, the answer is simple. This is criminality pure and simple. We don’t need to really understand what’s going on here. This is just people being criminals and looting on a mass scale. So we weren’t encourage to think of any possible links for what might have caused the riots. So no links to poverty, no link to lack of education or social upward mobility, and certainly we mustn’t think at all that this has something to do with the economic crisis. So what the government very strongly said is that there is no need for an inquiry. It was a sort of “let’s move a long, nothing to see here.”

Now, one of the things that was happening at the time is that one of the accusations that was being made, or that was being proffered by people who made sort of snap, knee-jerk responses to what was going on is that social media is being blamed. Social media was blamed for the worst civil unrest that England had seen in recent years.

And what was happening is that the three key platforms that were being blamed were Blackberry Messenger, which we later found out played a very very significant role in terms of being a closed network, in terms of being a very cheap technology that particularly people from socially-deprived, economically-deprived backgrounds could access. So a Blackberry handset is only about £40. You can have free messaging capacity for about £5 a month. So this was really being used. But on the pile was being thrown Facebook and Twitter as being blamed for these unrests.

whether it would be right to stop people communicating via these websites and services when we know they are plotting violence, disorder and criminality.

David Cameron, PM statement on disorder in England, August 11, 2011

[On the riots:] struck by how they were organized via social media.

David Cameron

https://twitter.com/louisemensch/status/101752383092162560

So who were the accusers? The usual suspects. The politicians. David Cameron was discussing whether or not people should be banned from using some of these platforms if they had been found guilty of using it for rioting purposes. And more worryingly, Louise Mensch, a Conservative MP, started making noises that were very very troubling. She was starting to say that social media might have to be switched off during the riots or during future events of this nature. So we have these politicians saying evil Egyptian dictators switching off the Internet very bad, but if we have to switch off social media for very legitimate reasons, then there’s no problem here.

People were getting arrested for posting certain messages on Facebook. And one of the things that was happening is the arrests were swift, the sentencing was extremely swift and very very harsh. This is someone who got four years for posting messages on Facebook, and this is one of the cases that really got a lot of media attention. These are two young men who posted a message on Facebook trying to organize a riot in a relatively small city in the United Kingdom, Northwich. And two things happened. One, they were very unsuccessful; nobody responded and nobody showed up. Except that somebody did show up: the police, to arrest them, and they got four years. They appealed their sentence, but the appeal was denied.

There were many people defending the riots on social media, saying the riots were not caused by social media. And one of the most interesting, I think, defenders of social media was actually the police, as well as many others. They argued that it was a vital platform for communication for them, in the sense that it allowed them to debunk rumors. It allowed them to reassure people, through this mass communication platform. And they felt that it was overwhelmingly positive for them to still have access to social media, particularly Twitter. This quote is from the Greater Manchester Police. The Greater Manchester Police is very forward-thinking in terms of their social media use, and so they were very outspoken about defending it.

Now, the general public, on the other hand, very much was in line with what the politicians were saying. This is a poll that The Guardian conducted of about a thousand people, where 70% saying yes we agree that during these very particular circumstances, BBM, Facebook, and Twitter might have to be switched off.

The biggest support for switching off came from people who weren’t typically using these platforms. So that came from people over 65. But I think it’s really worth remembering that there is a general public out there that was very supportive of these measures, and so this is worth bearing in mind.

Now, in terms of there not being an inquiry, The Guardian newspaper said this isn’t good enough. We need to hold the government to account and we need to find out what happened here. So they set about setting up this groundbreaking study called Reading the Riots, which is a collaboration with the London School of Economics, funded by two different funding councils. Our project is part of this, where we looked at Twitter and particularly what role did social media actually play in this.

So Twitter was of course very interested in finding out, because they were being accused of something they felt they hadn’t played any part in, their platform hadn’t been used in this way. And so they donated a corpus of 2.6 million tweets tweeted over that four-day period by 700,000 individual users. And what we looked at is the role of rumors. We looked at whether or not incitement actually took place on Twitter. And we wanted to look at the ways in which different users had come to prominence and were using the platform.

The Guardian, How riot rumours spread on Twitter [interactive charts non-functional]

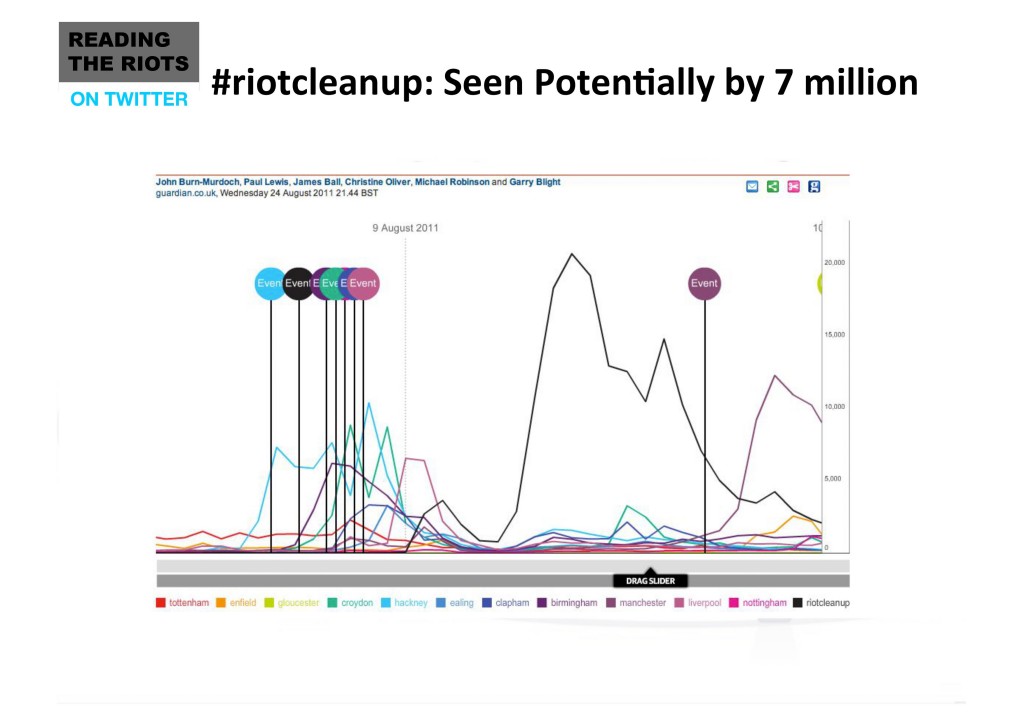

The Guardian produced a very early visualization of the different hashtags that people were using. And what you see is that people were using a localized version of the riot hashtag. So the first peak is in Tottenham, then we move on to Enfield. And what happens on day three is that the riot cleanup hashtag really spikes all of a sudden. It’s the black line. We calculated that this was seen by potentially seven million users at the time. And the Riot Clean Up account was set up in response to people trying to do something about this in their own community, so people going out in the street the next mornings and cleaning up the mess. This account, within a few hours, got over 60,000 followers. Then the final peak is when the riots came to Manchester and the local hashtag for Manchester started to become quite big.

One of the things we looked at was the role of rumors, and for those of you who know, there were some really outlandish rumors flying around at the time, including that animals had been released from the London Zoo; that rioters were frying their own food at McDdonalds; that a girl had been beaten up at the start of the riots by the police (This actually happened.); that the London Eye was on fire and had somehow miraculously been pushed over by the rioters; that the Birmingham Children’s Hospital was under attack from rioters’ that tanks had rolled into parts of London (This is actually a tank from Tahrir Square.); and that Miss Selfridge, a clothes shop in Manchester had been set on fire by the rioters, which actually also happened.

So some of these rumors turned out to be true. The rumor that I want to look at is animals being released from the zoo. What we did here is we coded this sort of mini corpus, this mini dataset of rumors. And one of the things we were interested in is the kind of information that people were distributing about this particular rumor.

What we divided it into is the green dot. And I’m going to play you the time sequence of the rumor. The green dots are people simply repeating the rumor: people simply making the claim “tigers have been released.” The red dots show counter-claims: that’s not happening, people might give reasons. Yellow dots show that people are asking questions: have tigers been released? Is this true? And then people also start commenting.

So this rumor plays out over a four-hour period, and what you see is that in the first instance, people simply repeat the claim and also ask, “Is this true? Is this happening?” So we see this claim being repeated, and the size of the bubbles denote that they are repeated more often. But what you start seeing an hour or so in is that there are some small red bubbles that start to emerge, and people are starting to say, “This isn’t true.” And what is interesting is that people are starting to offer information about why it’s not true. So what you see is that people say, “Hang on, that’s the tiger that escaped from the zoo in Italy in 2008. It’s a case of mistaken identity. It’s not London.”

But what is interesting to us is that when that kind of information is being distributed, you see a lot of red bubbles, a lot of counter-claims, and then all of a sudden they sort of start to disappear and a lot of green bubbles start to take over again and the rumor essentially starts to reproduce itself. So the claims that people are making again later on in the cycle, sort of towards the end tail of the rumor, are simply repeating the same claim again. What that really reminded us of is that people of course have particular networks on Twitter. We don’t see everything. We see who we are connected to, and so many steps further. So what we think happened here is that new people log on, say, “Oh my god tigers have been released, quick, retweet retweet retweet,” and the thing starts repeating itself until it’s finished and the rumor dies.

Now, although we didn’t find any evidence of incitement, what we did find (and I think this is rather worrying) is that when the coverage of the rumor work was in The Guardian and also when the visualization came online, people started using the project hashtag to celebrate that they had started the rumor. So people were saying, “It was me. I said that about the tigers,” and it made me very nervous about in future situations if people might actually start competing to get the best rumor adopted, or to get the best rumor picked up by some gullible researchers.

The other thing that we found was an enormous vitriol against looters. So, on the one hand we found no evidence of incitement, but what we did find is just an enormous sense of hatred and very explicit statements about what these people would do to the looters. I think there’s a real problem with this, that on the one hand Twitter was being celebrated as it was mainly used for positive purposes, but there was a very dark side to some of that communication as well.

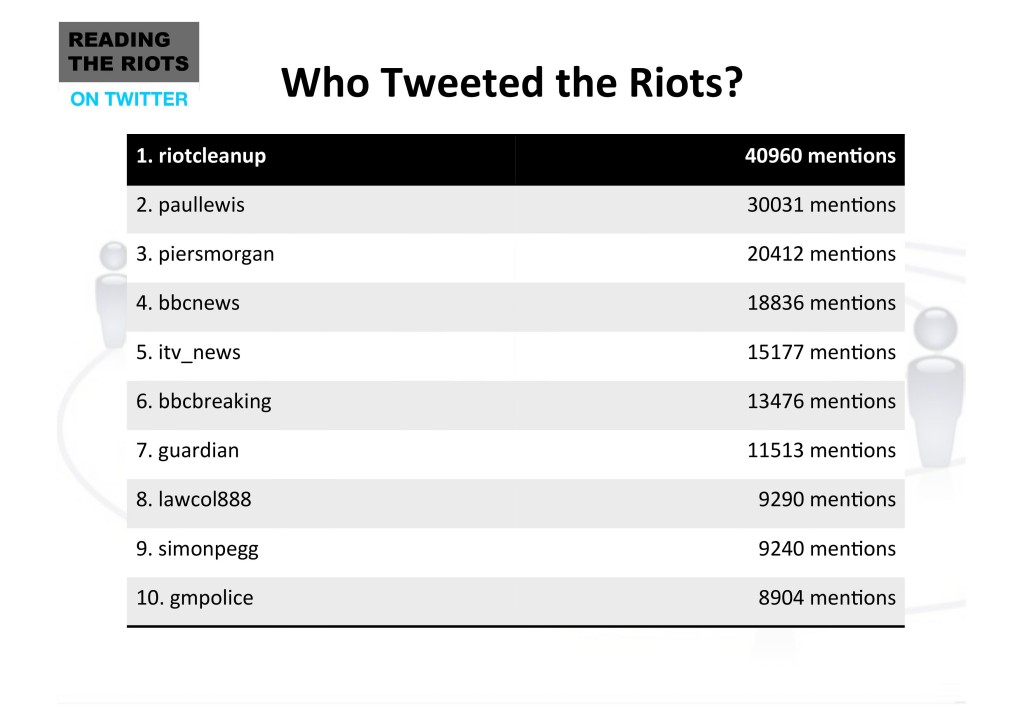

We looked at who actually tweeted the riots. So in terms of the 700,000 users, this is the top ten in terms of most mentions. So this isn’t necessarily how often people themselves were tweeting, but how often their accounts were retweeted, or how often that account was mentioned. And what you see is that again the Riot Cleanup account has over 40,000 mentions. So this is really clearly a very very important account during the time of the riots. We see a lot of mainstream media in there, and we see #2 Paul Lewis, the Guardian journalist who really was the key journalist in tweeting the riots and using social media as a platform for gathering information and so on. But we also see ordinary citizens in there. #8 is @lawcol888, who I’ll come back to, and we see the Greater Manchester Police at the end.

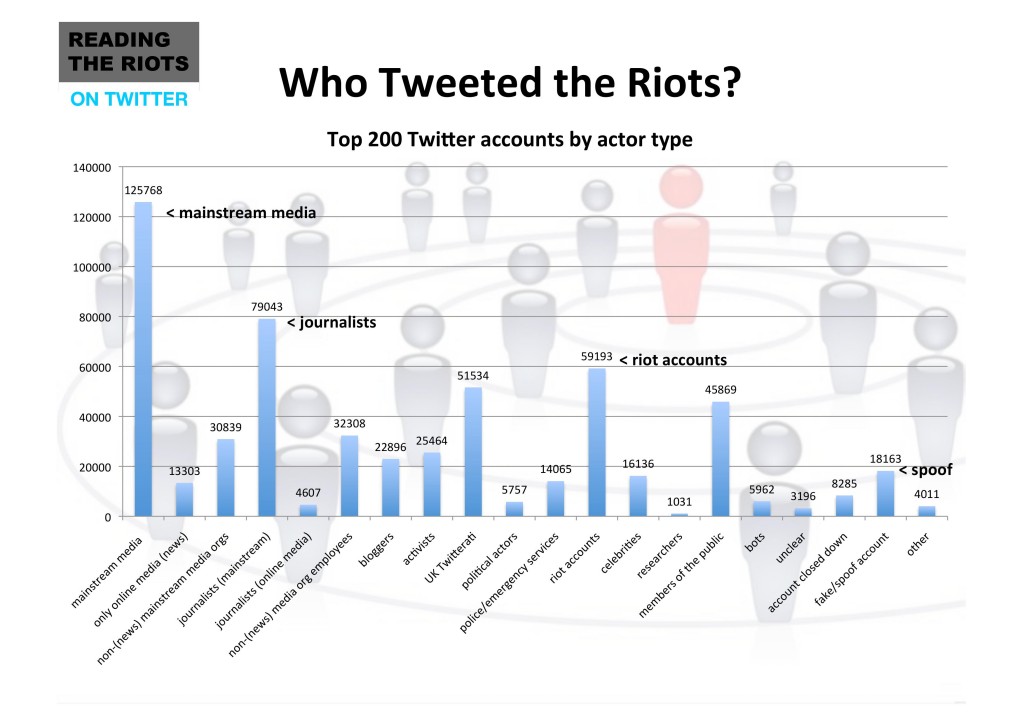

Now, Pierre, I offer my sincere apologies for this bar chart. We also built a typology of twenty different categories for how we could think about these users as groups. And one of the things that was very clear to us is that the mainstream media is really the most dominantly-cited group of accounts, followed by journalist. So mainstream media journalists were really all over Twitter. This is also linked, of course, to how often they are being cited, so there’s a lot of repetition in there.

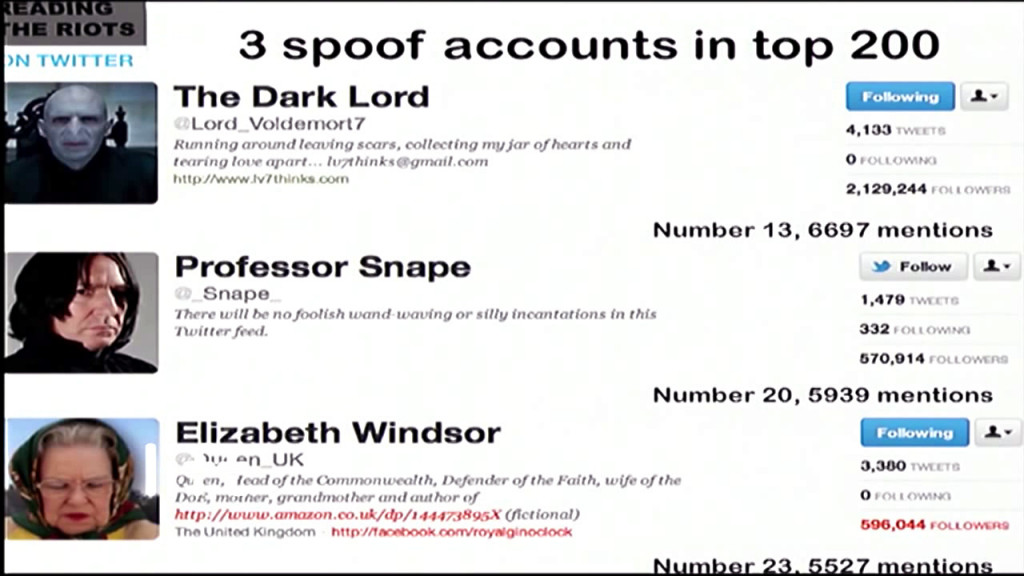

The other account that I want to draw your attention to is the third most mentioned category, and that’s riot accounts. One of the things that you often see in moments of crisis is that certain web sites or certain users will start curating an aggregating news and filtering news for the specific purpose of making it easy for people to find information about the riots. And of course a lot of these riot accounts were also riot cleanup accounts. So a lot of the riot cleanup in there. Right at the end, category 19, is spoof accounts, and I will come back to that. There were a lot of spoof accounts as well that were tweeting the riots.

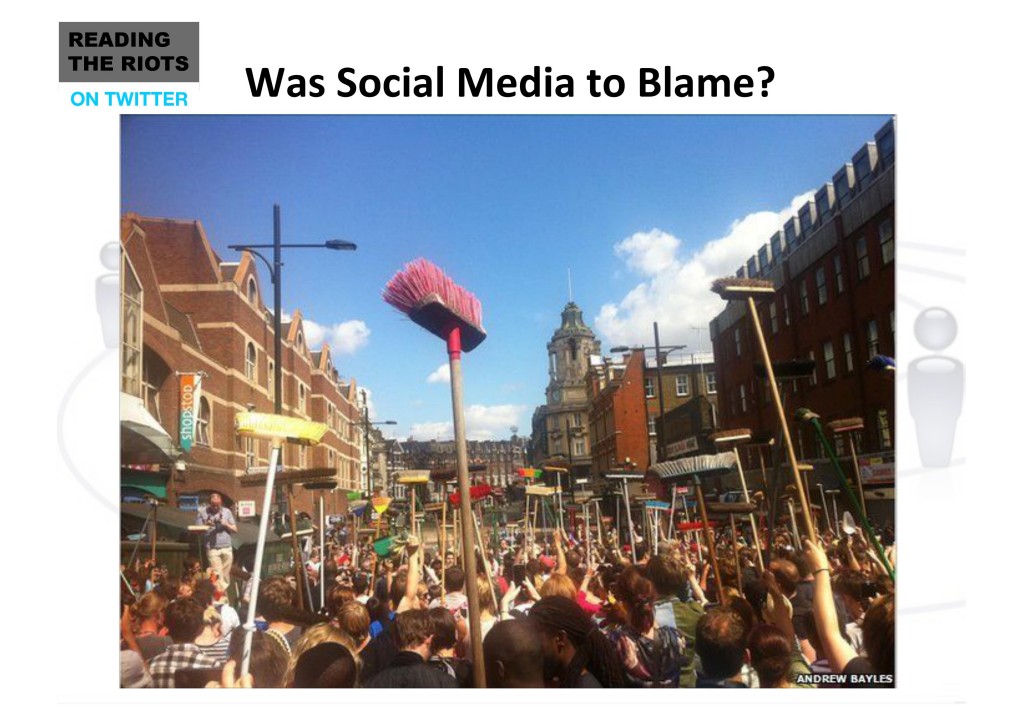

So just to summarize, we found a lot of mainstream media, a lot of journalists, Riot Cleanup was the most-mentioned individual account. But I want to also focus on the role of the emergency services, and just to highlight that Twitter was being used by lots of different users for lots and lots of different reasons. So people were organizing, people were broadcasting, people were collecting information, people were voicing opinion. This is for example Lawcol’s broom army photograph that went viral.

But what I want to move to next is people humoring the riots, and people satiring rioters, the riots themselves. And what we found is that in our top 200 most-cited accounts, we have these three massive spoof accounts that collectively are mentioned over 18,000 times.

So what is The Dark Lord, Lord Voldemort, doing at #13, having nearly 7,000 mentions in terms of his commentary on the riots? His sometimes-sidekick Professor Snape is in there. And of course the Queen. So what we see is a very British flavor in terms of satire and the way in which these spoof accounts were tweeting and commenting on the riots. We saw a lot of satirical comments commenting on the social situation at the time. So there was a lot of commentary on the Hackgate scandal, on Rupert Murdoch, on News International. And so one of the things that we found repeatedly, time and time again, in lots of different versions, is people saying, “What is the media saying? What is the police saying? You can’t get into Blackberry Messenger. Just ask some journalist from News International, why are you wasting your time?” So there were a lot of crossover comments about Hackgate and about what was going on with News International.

Finally, we found people uploading images of them planking in the riots. Planking was a craze that may or may not have taken off in Switzerland where people basically lie flat on different surfaces. This is a planking image from the Manchester riots. [slide not shown]

So just to reach my conclusions now, I think in terms of the dataset we have, we have a unique dataset here. I think we need to understand a lot more about the specific context, also the local context within which this information may have had a particular relevance. The rise of the individual I think is really interesting here, and various other commentators have reported this. We need to better understand how rumors can be contained, how information is distributed during crisis moments. And one of the key things is, I think, the role of the police, not just during crises but also during everyday situations.

In terms of predictions, Twitter is also a listening platform. 40% of Twitter users are inactive, they listen. What happens during crisis moments? Are people more actively listening? I think we need to understand this. How can the role of the police be improved, and what is the downside of that? What is the downside of the police being on Twitter more dominantly? And how can we build further teams across disciplines, but also across sectors, to be able to respond to these kinds of events more rapidly and offer deep analysis, and where would this move next? Where will crisis communication move next? What is going to be the next platform? Is it going to be livestreaming? And these are all the things that we’re very interested in exploring further.

Thank you.

Introducer: Thank you Farida. It’s quite interesting. Basically what happened is the opposite of what has been reported early on by the media. So there was no incitation to violence. People were mostly against the looters. I just wanted to explain if somebody is not familiar with Twitter, a hashtag is a code that starts with the hash sign that you put in your message, which means “I’m talking about this particular topic.” So you guys could follow the tweets that were mentioning riot cleanup, which was people talking about this topic of cleaning up the riots.

We had questions coming up, and somebody was wondering is there a way to legally punish people who start the rumors? Is there a way to pressure them?

Farida Vis: Well, I mean I’m no legal expert, but I think the fact that people were being sent to jail for four years over posting an unsuccessful message on Facebook certainly raised a lot of very serious questions. I’m not familiar with the legal aspects of what happens to people when they say certain things on Twitter. But what I was certainly struck by was that there was a focus on incitement, did it happen or not, and there wasn’t a focus on the vitriol and the way in which people were using very very ugly language to suggest “we’ll just shoot these rioters on sight; why don’t we set fire to them.”

Introducer: That was actually one of your findings. The violence was against the looters.

Vis: Against the rioters and very very aggressively and explicitly so, what people suggested should happen to them.

Introducer: A question. Why do we always want to cut Twitter or Facebook? Why does nobody want to cut the mobile phones or SMS?

Vis: Well, in this case it would’ve prevented a lot of problems.

Introducer: Why is it always the new technology we blame for everything?

Vis: It’s the shock of the new. It’s the shock of the unexplained, of the unknown, and the imagination that I think turns it into the next boogeyman. And so I think I didn’t speak about YouTube, but YouTube is another one that’s often linked as a hotbed to extremism and so on, and there is no real empirical evidence to suggest that this plays this role. It’s just I think in policy domains, there’s this imagination about what social media is capable of or what it’s actually doing

Introducer: What will happen in the next crisis? Do you think David Cameron will think twice before asking to cut Twitter, or that MP? Or do you think that it was a learning experience for the whole country, and the next answer is going to be smarter? Or do you think actually it’s really two worlds that are dividing and not coming together?

Vis: I think it was a very steep learning curve, also for us as an academic team. But I think what happened in that moment was that everyone was really really willing to learn and do kind of scary stuff. So to work with Twitter and The Guardian, and then a team of academics, I think in that innovation something else happened that now means that we’re working with the police, we’re advising on their social media strategy, we’re working with different government agencies advising them on their social media strategy. And so I think what people are really aware of is that this thing, social media, is not going to go away. Twitter is not going to go away. It might go the way of MySpace at some point, but there will be a new version, there will be a new thing. And so one of the things I was really struck by is that the police is very interested in well, how could we use this effectively during the next mega-event that’s going to generate a lot of tweets? And that’s of course the Olympics. So that will be the next mega-event that we’ll be looking at.

Introducer: Maybe to make them feel better you can tell them about Anaïs’ point that social media were invented in 1634.

Vis: I know. I will put them in touch with Anaïs.

Introducer: Thank you very much. Farida Vis.

Vis: Thank you.

Further Reference

Presentation description [Wayback] at the Lift conference site, and at their video archive.

Farida’s slides for this presentation.