Rashad Robinson: So I’m sort of kinda last here this session, and I’m sort of standing in between everyone and drinks and food. So I want to inject a little culture into this conversation. And as we talk about the reasons that we make interventions in this work, the reason why we advocate for truth in the media, and the reason why organizations like mine do that work is for our community, for the folks that we represent.

This is my niece and my nephew Camden and Elon. And we do the work because we want the world to look better for them five years, or ten years, or twenty years down the line. And the work that we do at Color of Change—I’m also going to actually spend some time talking about the work I did prior to Color of Change—is about the truth in how do we— Who gets to identify who we are? Who gets to talk about our voice? Who gets to define us as people in the media and determine the names that we’re called, the labels that are used to define us?

Two and a half years ago, Glenn Beck went on Fox News and called President Obama a racist with a deep-seated hatred for white people and white culture. Color of Change at that point mobilized over the course of two and a half years over 285,000 of its members to get over 300 advertisers to remove its sponsorship, making Glenn Beck no longer profitable to Fox News. And it was a victory. It sent a message. But it wasn’t necessarily a systemic change, right. So shortly after Glenn Beck leave the air, Eric Bolling replaces him and starts talking about why Obama is you know, drinking forties in Ireland.

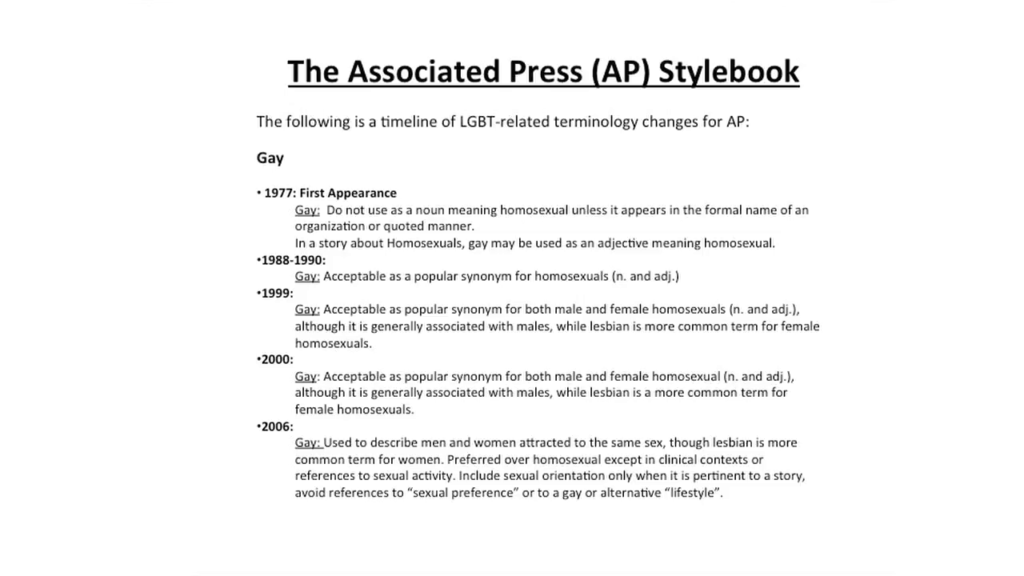

And so I’m going to talk about a little bit of work I did when I was the senior director of programs at the Gay and Lesbian Alliance Against Defamation. I’ve been gone from GLAAD for about a year now. But we did a lot of work in terms of terminology, and working specifically with the Associated Press in how they define gay and lesbian people. The work started before I got to GLAAD but it was sort of work that took place before GLAAD existed, and then that’s currently being done even today.

And it really centers around the word “homosexual.” In 1973, the American Psychological Association removed it from its list of disorders. It still carried a lot of pathology to it. It was a clinical term, and it was consistently used by folks who opposed freedom for gay and lesbian people. It’s been used over and over and over again by by opponents to equality for gay and lesbian people, or laws that were being advanced around the country. The Washington Post, AP Style Guide, Reuters, and The New York Times all sort of listed homosexual as a word that could be used.

And the work really started in the 80s, by getting The New York Times to just start using the word “gay.” To just say start using the word “gay” along with using the word “homosexual.” You know, that was a victory. Over time the community started advocating and pushing the Associated Press to start figuring out how they were going to remove the word homosexual from its style guide, listed as a pejorative term. The AP, as they do with sort of a number of terms, says that, “We don’t make that decision at the national level. We really follow the trends that are happening all across the country.”

And so that’s when the community was engaged. Community members all around the country were engaged every time “homosexual” appeared in a local AP story, in a state AP wire, that they would start getting phone calls to change that. And over the course of about four to five years, it got to a point where virtually the word homosexual, you did not see it in any paper sort of across the country. Where I got to the point where the Associated Press had to make a decision about what it was going to do next.

And so we had a meeting with the Associated Press to sort of look at what we were going to do next about were they going to keep the word “homosexual” and just add “gay?” Whether they were going to say you probably shouldn’t use the word but if you want to use it as a synonym it’s okay. There was a lot of back and forth over the course of a year, a lot of research was brought in. And they eventually removed the word “homosexual” and listed it as a pejorative.

The work didn’t end there. It actually sort of intensified at that point. That’s when we had to make phone calls every time we saw it come up. That’s also when a lot of work was done by our opponents to start making sure that any time they saw the word “gay” they would switch it to the word “homosexual.” So I have a funny example here of a track runner named Thomas Gay.

This comes from the American Family Association’s news wire. They take AP stories and they change—every time the word “gay” appears and they change it to “homosexual.” And so thanks to some great staff at GLAAD and some fantastic gay bloggers, we were able to catch this and get a number of screen shots across the Internet. Not just of Thomas Gay but of the Boston Celtics NBA player Rudy Gay, who some of you may follow here, who’s also been Rudy Homosexual as well. Probably much to the surprise of their family and friends and close associates. It kind of makes for really interesting titles like “Homosexual Eases into 100 meter Final at Olympic Trials.” Probably not what the American Family Association really intended, but really shows sort of the power of words and the power that words have in sort of defining a community.

We worked after that with Gallup in trying to get them to change how they were using the word “homosexual” in their polling. And they said, “We need longitudinal integrity, so we don’t want to change the terminology that we’re using. We want to be able to compare how folks feel about the homosexual community in 2008 to how they feel about the homosexual community back in you know, 1986.” And so we found some polling that they did in the 70s around, “If all things were equal would you vote for a Negro for president?” And they certainly were not using that polling during that Hillary Clinton/Barack Obama primary. And they had made some changes around longitudinal integrity at that point to sort of suit cultural changes and the changes around how we determine how community has agency around who they are and [how] they’re defined. What’s actually their truth in the media. And so those changes were made.

You know, this is about truth. It’s about how folks are defined. It’s also about— You know, I know that we’re having these conversations around is this a left or right conversation. And so I will be completely transparent. “Would you be okay with homosexuals teaching your children?” versus “Would you be okay with gays and lesbians teaching your children?” is ten point. It’s ten points. But it’s also about how the community wants to define how they see themselves, how they should be represented.

And so when think about interventions and as organizations like Color of Change, or GLAAD, or organizations that represent community—everyday people that want to think about how their children are going to experience the world ten years or five years down the line, it really is about how do we sort of define and engage media to not just look at sort of what we consider as basic facts, but sort of how do our lives, how is our dignity, and how the labels that are used about us represent who we are and who we should be in the press.

Further Reference

Truthiness in Digital Media event site