Jonathan Zong: Hi. My name is Jonathan Zong, and I’m currently a student at Princeton University in the computer science and visual arts departments.

I care about the Internet. After all, I’m…kinda on it a lot? And we’re all here because we want to make the Internet a better place to be. And as many of the talks today have shown, experimentation is a great tool for finding effective ways to improve the online experience.

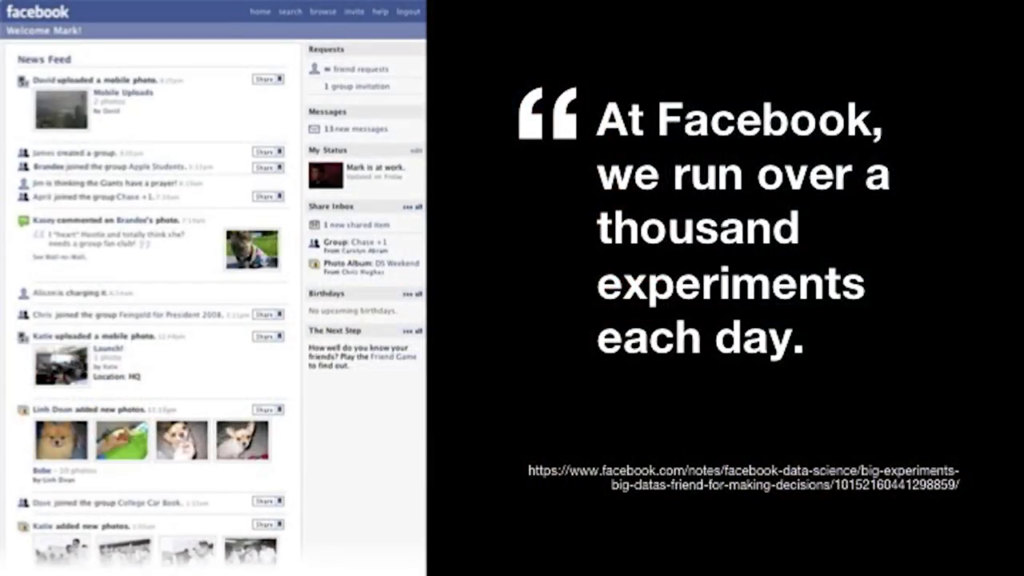

And actually, experimentation is so commonplace on the Internet now that if you use a platform like Facebook you’re probably part of many experiments all the time.

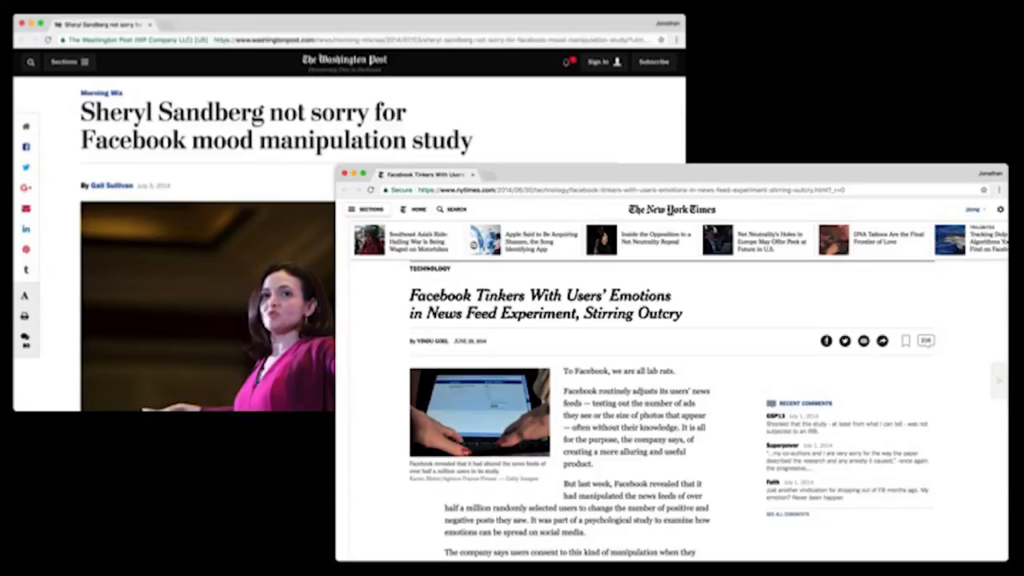

Sheryl Sandberg not sorry for Facebook mood manipulation study;

Facebook Tinkers With Users’ Emotions in News Feed Experiment, Stirring Outcry

So, what happens if there’s an experiment that is making an intervention that’s too risky compared to the possible benefits? This happened, for example, in the Facebook mood study, where Facebook altered users’ news feeds to show them more happy or more sad content on average, and measured that users were more likely to post happier or sadder things themselves depending on what they were shown. And a lot of people were pretty upset about this.

Consent & Accountability

So I bring up the Facebook example not to wag a finger at them but to highlight what we can learn from the public reaction to this. Experimentation that doesn’t have public accountability is risky, because there’s no shared consensus about what values are important for the research to uphold. So, in the case of Facebook’s study, the users weren’t informed beforehand that they were part of the experiment and there was no other kind of external accountability to compensate for that.

So if you were trying to do some research like the kind that CivilServant does to improve online communities, how can you hold yourself accountable to the public? Because in online research, it’s not always possible to get the consent of everyone involved in an experiment beforehand. There might just be too many users in your community, or a variety of other reasons that make it impractical.

Well, I’m a researcher at a university, and what I would do is I would go and talk to an institutional review board, or an IRB. Unlike Facebook, researchers at universities are required to have their research plans approved by an IRB before they can do the research, for ethical reasons.

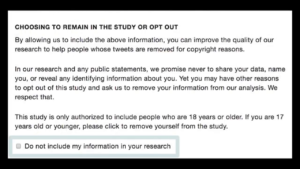

And what the IRB would tell you is that if you’re going to forgo consent for an experiment, three conditions have to be true: The study must have minimal risk. It must actually be impractical to obtain the consent. And there must be a post-experiment debriefing. And debriefing is this process where after the experiment is over, users that were part of the experiment are informed about the experiment and they’re given information about what the experiment was for, what data was collected… And debriefing serves this important ethical purpose by allowing people to ask questions or even opt out of the research. And successful debriefing can really empower people to make informed decisions about their involvement in research.

User interfaces for debriefing

So, what if we could design user interfaces that help us automate debriefing and reach a large number of people involved in these huge online experiments, and give them detailed information about their involvement in research?

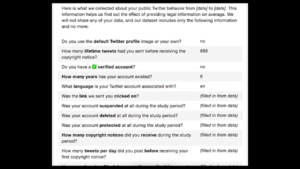

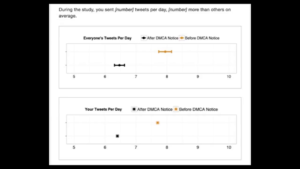

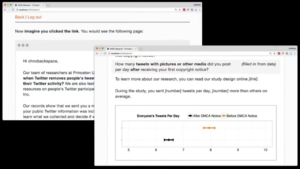

This is a project that I’m taking on at Princeton, under the mentorship of Nathan Matias. And some of the ideas that we’re testing out are for example generating tables that explicitly show what data we’re collecting and showing this to participants; explaining our results visually, so that people can understand how the results impact them; and of course, providing controls for people to opt out of data collection and remove themselves from the research.

Testing a debrief interface

So we’re currently doing a study to test these ideas about automated debriefing. And with the intent of supporting Merry and Jon’s work on copyright enforcement, we’re asking users on Twitter who received copyright notices to imagine a hypothetical scenario where they were involved in experiments and presented with this debriefing interface. And we’re asking them to give feedback on whether or not they would find the interface helpful to them.

And what we learn from this will not only tell us more about debriefing but also allow us to do things like forecast opt-out rates for similar groups of people in the future. And just generally get a better sense of people’s attitudes about research. And this presents an alternative to Facebook’s procedure in the mood study by setting up this public accountability structure that is based around this conversation about acceptable risks.

So I want to end on the thought that research ethics isn’t just a matter of compliance but it’s actually essential to why we’re doing the research in the first place. Because we want to make the Internet a more positive presence in people’s lives. And together we can set common procedures and shared norms that can help us do just that. Thank you.

!["We should engage [research ethics] issues directly and work toward shared norms" —Scott Desposato](http://opentranscripts.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/jonathan-zong-research-ethics-00_01_51-1024x576.png)