Liliane Wong: Good morning. And I want to thank Damian for inviting me to his jamboree. I believe I probably fit into the lineup because of our focus in the department on adaptive reuse. And so today I’m going to switch scales from the other presenters and show you a project of one of our graduate programs which is not so much about design and the power of our designs, but rather about helping those who we need to include in design for HR 109 to go forward. So, it is about convincing the non-architects to give a damn about sea level rise.

In many ways the contemporary relationship of climate change and adaptive reuse can be traced to the early 2000s. In addition to other findings of that time, buildings were deemed responsible for almost 40% of the annual global greenhouse gas emissions. Organizations such as Architecture 2030 and their challenge for the building industry to reach net zero included a consideration of the existing building stock. The recognition that two thirds of the two and a half trillion square feet of buildings that exist today will still exist in 2050 set the stage for Carl Elefante, future president of the American Institute of Architects to make his 2007 statement that the greenest building is one that is already built.

The pedagogy of INTAR, or the Department of Interior Architecture at RISD focuses on exactly that, buildings that are already built. And while the reuse of existing structures has been with us since time immemorial, its professional recognition as adaptive reuse did not come about until the first decades of the millennium, through the advocacy of those such as Elefante. A recent study of the National Trust finds that it takes ten to eight years for a new building that is 30% more efficient than an average performing existing building to overcome through efficient operations the negative climate change impacts related to the construction process.

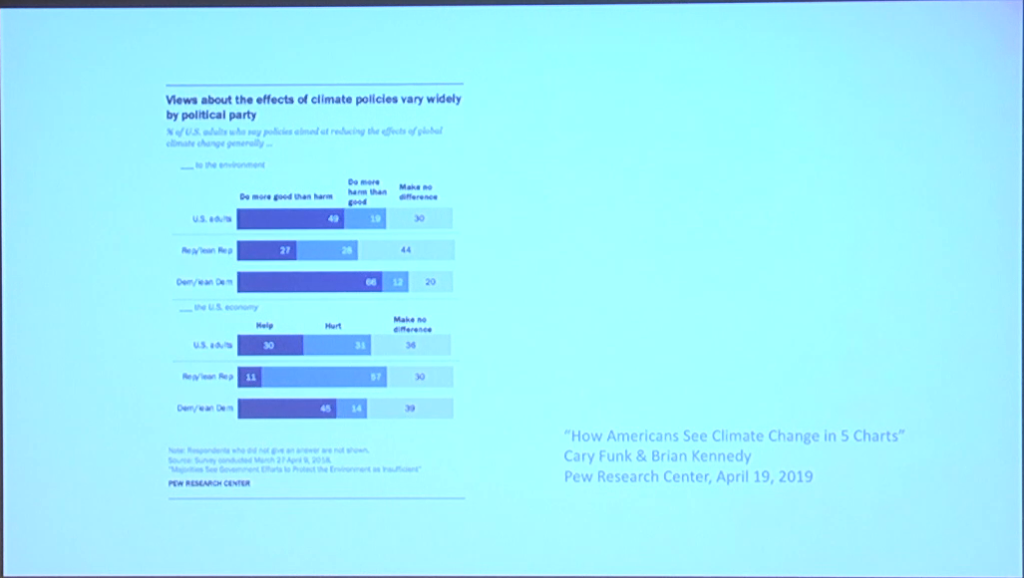

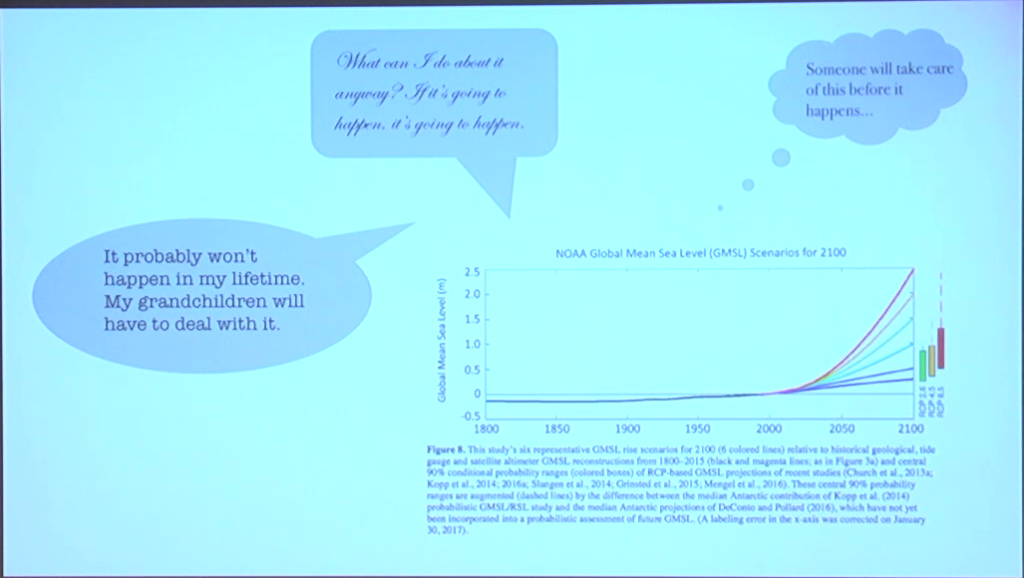

As the antithesis of demolishing, the act of reusing an existing building is a commitment not only to the environment but to the many embedded histories and social contexts of that structure. The coupling of environmental concerns with social ones is a characteristic that adaptive reuse practice shares with the Green New Deal. The passage of HR 109 in the near future will depend on many factors, including public opinion on climate change. A survey taken a few months after the introduction of the Green New Deal indicated what we all know, especially in an election season. And that is that climate policies vary by political party.

But, partisanship aside, the Pew Research survey showed us two important pieces of information. First that 49% of all US adults believe that policies aimed at reducing the effects of global climate change generally either do more harm than good to the environment, or make no difference. Second, that 60% of all US adults believe that policies aimed at reducing the effects of global climate change generally hurt or make no difference to the US economy. A successful passage of the Green New Deal requires a sea change of such attitudes.

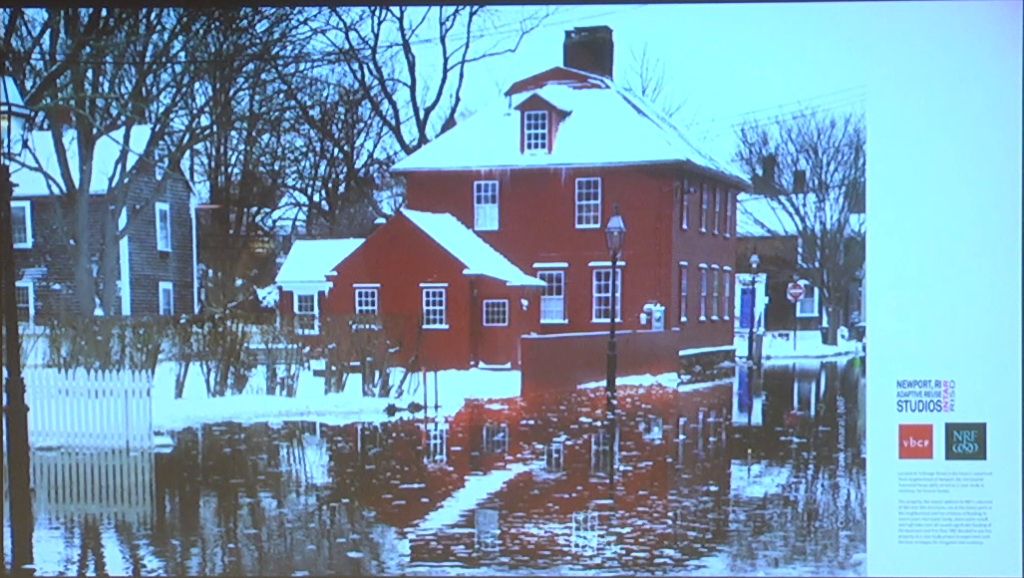

Sea and change are the subjects of a project I would like to share with you today. Sponsored by the Van Buren Foundation and the Newport Restoration Foundation, Projecting Change was part our post-professional MA in Adaptive Reuse program. It was inspired by the effects of Hurricane Sandy, which turned Newport, Rhode Island into a lake. Since then, Newport’s oldest neighborhood, The Point, and our site, floods from the storm surge of every heavy rainfall.

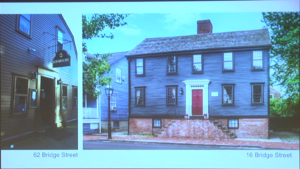

Built on grade and characterized by close-set two-story houses, the 17th century neighborhood lacks preservation guidelines for flood management. Without such regulations, those who can afford to raise their homes anywhere from three feet to six feet above ground do so, and without regard for its impact on their close to 400 year-old neighborhood and their neighbors.

This action created a phenomenon, termed lollypopping, which changes the characteristic of the historic community. The objective of our studio was two-fold. The first was to propose inclusive alternatives for this historic community as they look into a future with sea level rise. With this first objective in mind, the studio examined the term “preservation,” classically defined by James Marston Fitch as the maintenance of the artifact in the same physical condition as when it was received by the curatorial agency. Nothing is added to or subtracted from the aesthetic corpus of the artifact.

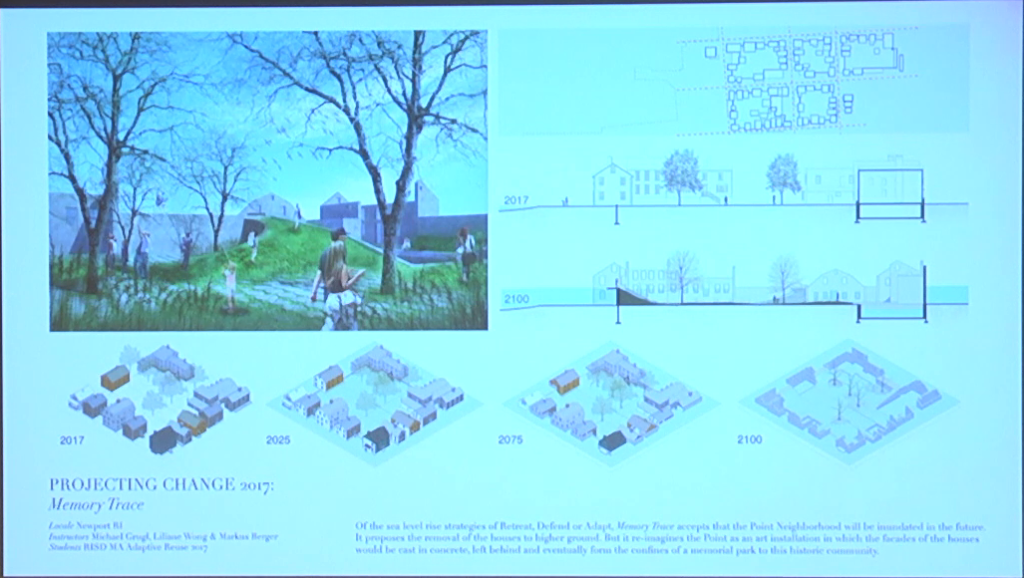

Of five total projects in the studio, four reinterpreted this definition. Accepting that the Point neighborhood could not be maintained in its present location in rising seas, the project Memory Trace chose to retreat as a strategy. Assuming future inundation, the project relocates the neighborhood to higher ground but leaves a memorial consisting of the cast facades of the houses themselves. This proposal maintains Fitch’s requirements for the physical buildings, but on a different site.

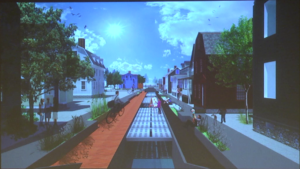

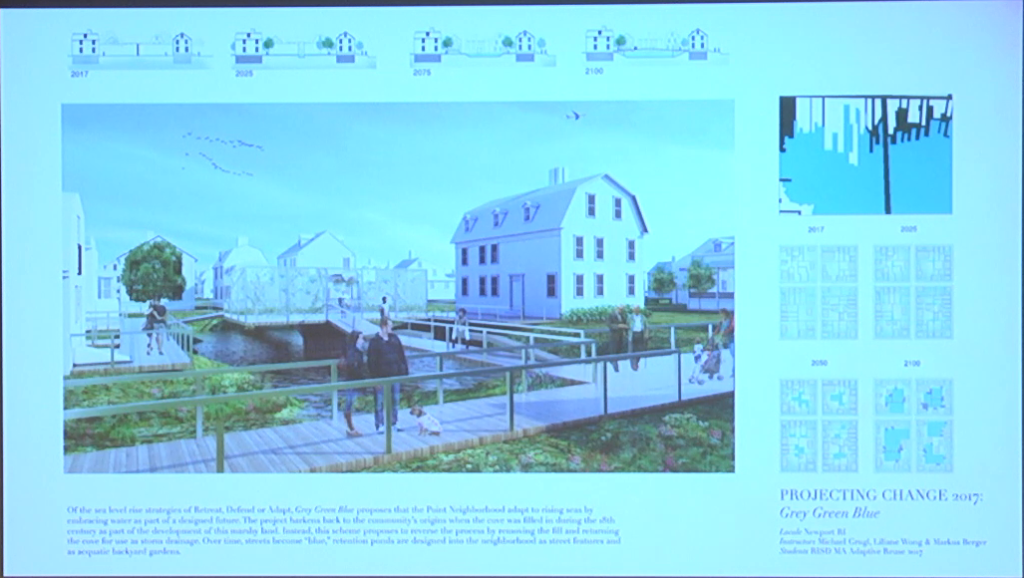

In contrast, Grey, Green, and Blue uses an expansive strategy of both defense and adaptation in order to maintain the Point neighborhood in its historic moment and in situ. A breakwater is proposed to defend the community, a wireless system of blue streets and retention ponds are created for accommodating the water over time.

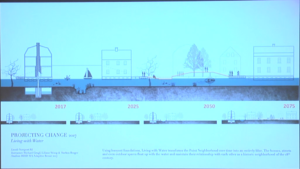

Living with Water employed more experimental means to maintain the neighborhood exactly as it was. Assuming rising waters, the project proposed to replace all existing building and infrastructural foundations with buoyant ones. Tethered in place, each house would rise and fall in place, and together with the water as it rises over time.

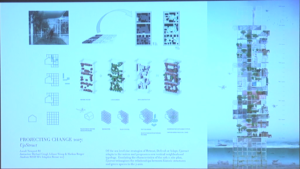

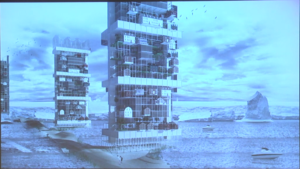

Upstruct instead proposes to update Fitch’s definition of preservation in the face of climate change. It posits that if the historic community as we know it today is premised on a horizontal configuration on land, why not redefine this relationship through a configuration defined by the water. Upstruct offered a new vertical grid that maintains the relationships of the historic houses to each other, but through a different axis. And in this case the Z.

These solutions take The Point together as a community into the future, but they did so as drawings, models, and renderings that privilege those who understand such representation.

The second objective of our studio was to make these designs for sea level rise accessible to all members of the community, many of whom in an initial interview corroborated the findings of the Pew survey. And I should say that this second objective really was the primary objective of our sponsors.

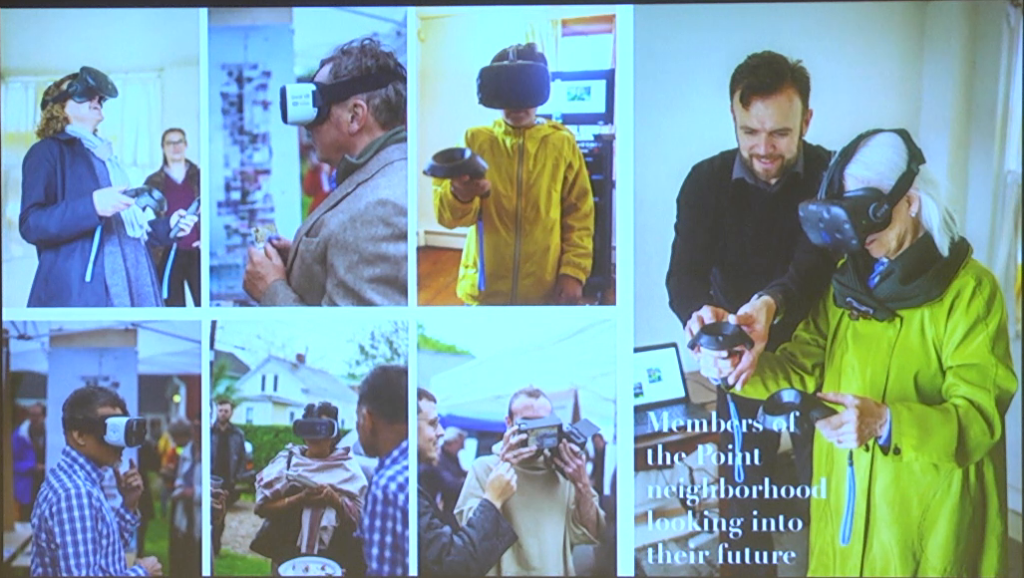

To achieve the second objective, we used both virtual and augmented reality to display the four projects to the citizens. With augmented reality markers placed around the neighborhood, members of the community were able to see right on their phones the streets turning blue, retention ponds spreading into their gardens, or their house flying into an upstruct configuration. Visualization of this form allowed neighbors from middle schoolers to octogenarians to finally see what sea level rise might look like for their immediate surroundings.

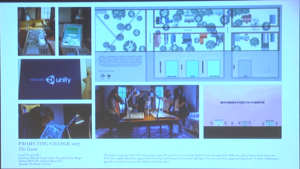

The fifth project in the studio did not take on rising seas through designs. Rather, using augmented reality a game was created with the neighborhood as its game board, and the saving of one’s home as its objective. With one’s home as the game piece, a team of players collaborated against a countdown to put the interventions in place.

The game contained four level challenges, each implementing a different design intervention for combating sea level rise. Built on the concept of user interactions and feedback, the game holds a set of challenges which can only be mastered in teams, and is designed in such a way that it cannot be won by a single player, no matter how capable.

At the end of the countdown, simulated water floods the game scene to reveal whether or not the players managed to save their neighborhoods. The greater the collaboration amongst the players, the higher the resulting score, conveying the need to collaborate if sea level rise is to be managed to successfully.

A Warning From the Garden, Thomas L. Friedman

These projects all utilize visualization to allow one to see beyond what one can understand. On a January morning in 2007, daffodils bloomed months earlier than they should have. The physical presence in the depths of winter of these golden harbingers of spring was the physical proof of the effects of climate change that caused Thomas Friedman to write his now-famous New York Times op-ed A Warning From the Garden and to coin the term “Green New Deal.”

As we look to gather consensus on climate change and pushing forward HR 109, visualization might be instrumental for allowing everyone to see into their future so as to take action now. Thank you.

Further Reference

Climate Futures II event page