Sarah Newman: As Daniel said, thank you for being here. I’m very excited today to introduce Ian Bogost. He is the Ivan Allen College Distinguished Chair in Media Studies and a Professor of Interactive Computing at Georgia Institute of Technology. He also holds an appointment in the Scheller College of Business.

He will be in dialogue with Jeffrey Schnapp, who is a faculty director of metaLAB, a co-director of the Berkman Klein Center for Internet & Society. And he is the Pescosolido Chair in Romance and Comparative Literatures here at Harvard.

Today, Ian will be talking about A Pessimist’s Guide to the Future of Technology. As we were just discussing, pessimism is clearly popular based on the turnout today, and rightfully so. [audience laughs]

Jeffrey Schnapp: A vote of confidence.

Newman: And rightfully so. In this age of celebration of technology it’s really important to have the critical in dialogue with the celebration and the embrace of technology that we have here at the Berkman Klein Center and our our extended community.

Ian is also the author or coauthor of ten books. He is the cofounder of Persuasive Games. He is a game designer and scholar. He is also a contributing writer to The Atlantic, and is a coeditor of the Platform Studies series published by the MIT Press, and the Object Lessons series published by Bloomsbury and The Atlantic

Jeffrey is a cultural historian whose interests range from antiquity to the present. He is also a pioneer in the digital humanities and his works range from books to curatorial practice and beyond.

The emphasis of Ian’s talk today will be on autonomous vehicles as a test case, and the dialogue should be really interesting because Jeffrey just completed teaching a course on robots in the built environment here at Harvard.

Ian Bogost: [Aside to Schnapp:] It’s almost like I was thinking about this.

Newman: I also learned recently that Ian has an unusual perspective on what constitutes a sandwich, which might include a head of lettuce, and this is might be interesting to those in the Berkman community because we’ve been talking about sandwiches recently.

Bogost: Yeah. Just, everything’s a sandwich.

Newman: Exactly.

Bogost: Let’s just get it over with.

Newman: So with that, thank you for being here. And we’ll make sure we save some time at the end for questions.

Bogost: Great. Okay. I am so happy to be here. I just flew in. So you welcome me with this nice rainy weather, which I’ll forgive you for.

When I was a first-year undergraduate philosophy student, I had this very stern and severe Scottish instructor. And he was kind of against everything, it seemed. And we were talking about Kant, Kant’s moral philosophy, of course the categorical imperative. And the idea of the categorical imperative is that according to Kant one should act on a maxim only if one can imagine it becoming a universal law. This is sort of the one-liner on Kant’s moral philosophy.

And you know, philosophers are kind of trolls—kind of the original academic trolls, right. Nothing makes them happy, they’re very grouchy about everything, it’s all about sort of sneers and barbs and daggers in the side.

And so this instructor had this counterpoint, a sort of reductio ad absurdum to Kant’s world moral philosophy, which apparently I’ve not forgotten and will never forget, which was okay well if you should act on every maxim as if it should become a universal law then this should work for every maxim, according to Kant. Anything that you can suppose should be testable for its moral quality against this premise.

So what about I will play—in order to exercise and keep myself physically fit, I will play tennis in the mornings at ten o’clock AM. So if you run that scenario and you say well, imagine if everyone played tennis at ten o’clock in the morning in order to keep physically fit. Then it breaks down because everyone would crowd the tennis courts, no one could play tennis at all, therefore you must not play tennis at ten o’clock AM, which of course seems preposterous. So this is you know, one way of thinking about these ideas that doesn’t seem quite right but is insightful in the sense that it shows that there are these reversals, these kind of edge cases; at their negative ends or at their extremes, things change. They change form. And so something that’s sort of thinkable in a reasonable way at the center, once it moves to the edges and then once the center moves to that edge, then it alters somewhat, it changes.

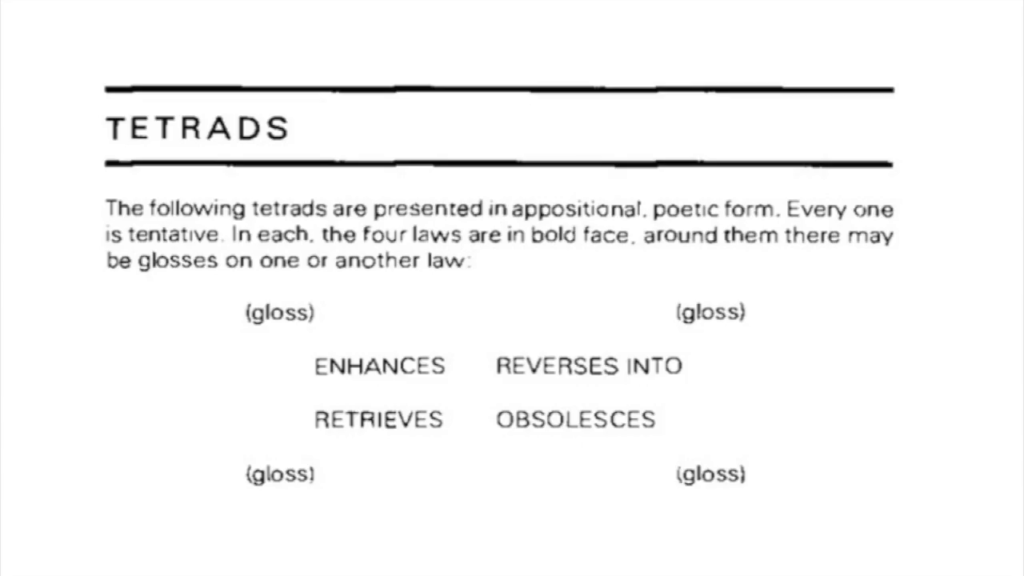

Now, Kant’s maybe not the best tool to think about this. But Marshall McLuhan and his son Eric in this book that no one reads unfortunately, called Laws of Media, have this interesting media philosophy of these four laws which you see here: enhancement, retrieval, reversal, and obsolescence. And we don’t have time to go into all of this but what’s interesting about it for the present conversation is that for the McLuhans, this idea of reversal is kind of like a property of media. It’s not something that happens later when things go wrong. It’s an intrinsic property that all four of these laws are kind of active on media objects. And of course for McLuhan everything is kind of a media object—that’s the electric lightbulb, famously, and so forth.

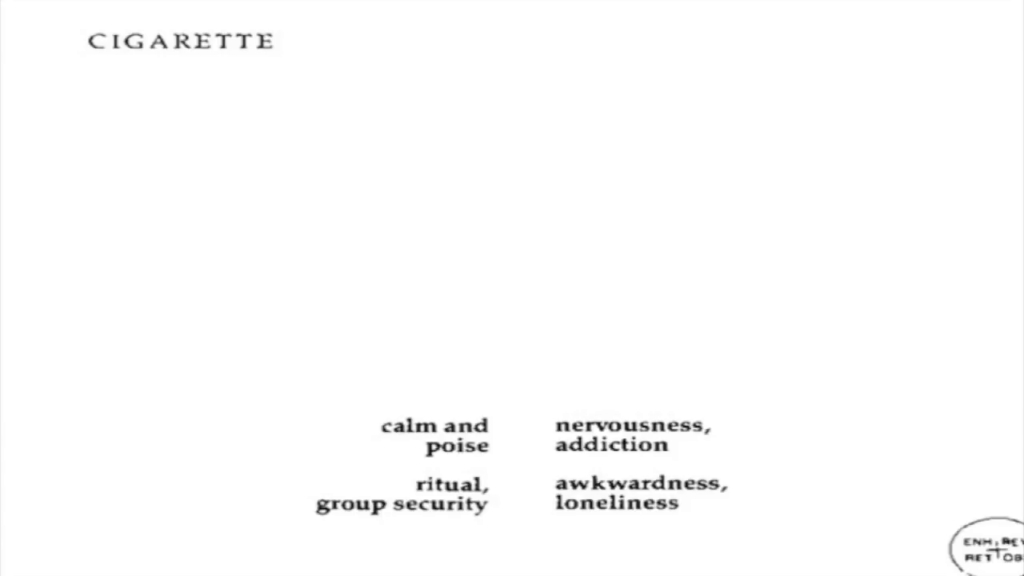

And they run these scenarios in this book of these tetrads. This is the cigarette, which enhances calm, and retrieves group security—you can all go together and smoke. And the reversal, the thing that happens when the cigarette is pushed to its extremes or its limits is it becomes this addiction, right. Your nervousness. You’re no longer calm because now you want the cigarette that you can’t have.

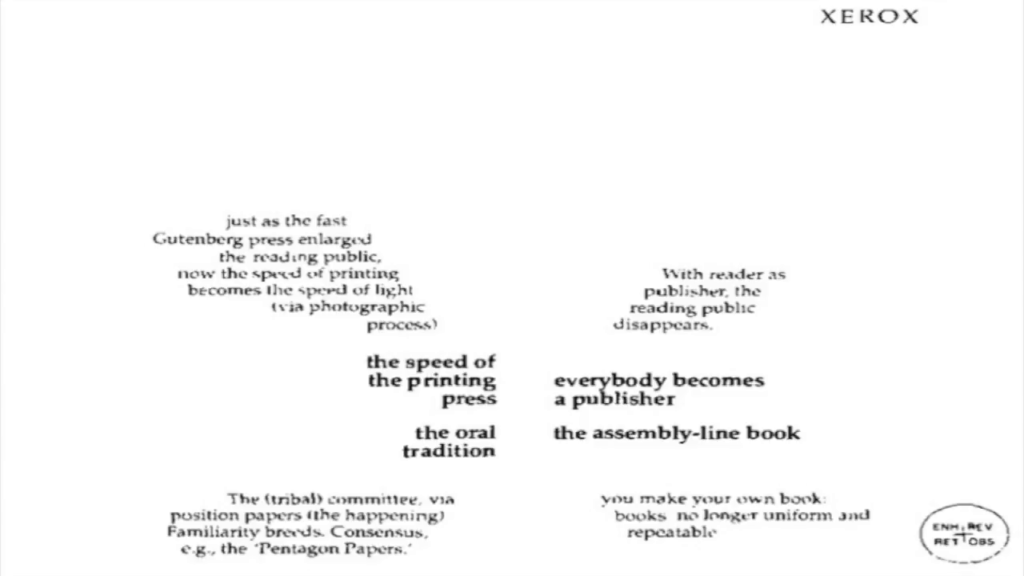

There are dozens of these in this book. This is the Xerox machine. I guess the interesting thing about the Xerox is the reversal scenario from the McLuhans is that everybody becomes a publisher, which is something we used to talk about in a very positive way and now we’re not quite so sure about any longer.

Or maybe this example. This is the car. There’s all sorts of interesting and bizarre things going on here, and we again won’t take the time to unpack them all. But the knight in shining armor is the retrieved medium, this idea like there’s something from the past that comes to the surface in the presence. So I guess this— You know you can now get out of any situation—certainly this is what car share services are like now.

But this is obvious that the car when pushed to its limits, when everyone has a car, everyone is in their car at once, then you get traffic which is the opposite of mobility and free— It’s interesting that freedom and mobility are not the thing that the McLuhans identify but privacy. But it’s okay, this is just a tool.

And it makes perfect sense. And so I give you this example in particular not only because we’re going to talk about autonomous vehicles a little bit, or I’m going to riff on that a little bit. But also because you can see how it just makes sense. That it’s not that there’s something wrong when you get traffic jams. There’s something intrinsic to the design object that is the automobile in its urban context that is traffic. That’s part of what the car is. And that’s the insight that the McLuhans had in this tool.

Now, the pessimism business was a little bit of a… I don’t know. I mean, I am I think a natural pessimist. But in this moment that we’re in today with technology, where we’re I think shifting finally into a mode where it’s possible to be critical without getting sneered at, if we kind of look back at the…I don’t know, the optimistic aspirationalism that we’ve been using to encounter technology in the broadest sense, and we look back on those moments of the recent past or even the distant past, we can see how we knew how things were going to turn out, actually. We just weren’t paying them heed.

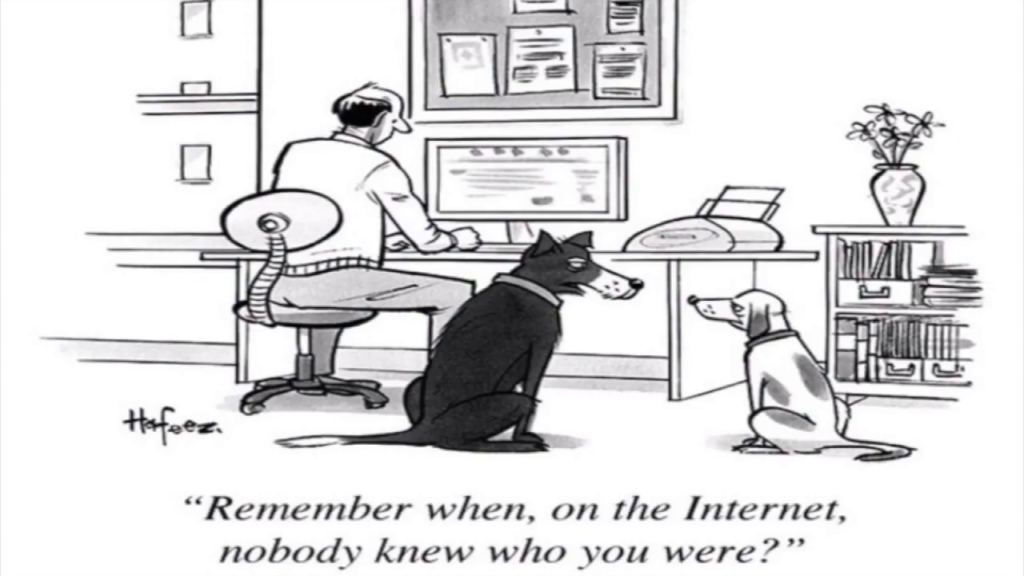

So you know, we kind of knew twenty-five years ago that the notion of identity and anonymity online was troubled. We knew that. And we just made jokes about ha ha that’s funny, let’s move on, right. But that turned out to be an intrinsic part—for good and for ill, right.

Or this is from about— Well, it’s 2006. You can see back when we were celebrating how blogging was going to do away with these gatekeepers that were keeping people out of sharing and spreading ideas and that was just terrific. And you know, okay well what happens? Just think about it for like ten seconds. What happens when any idea can be shared and can’t be distinguished from any other idea? Well, you have no quality control and no ability to discern which ideas are sort of even not just desirable but even true.

We knew this and we just kind of went headlong into it, thinking well this is great. Nothing can go wrong.

Or with these devices, which I’ve previously called the cigarette of the of the 21st century, these gadgets.

The relationship— I feel mine buzzing in my pocket literally right now as I’m talking. The relationship we have with our smartphones universally, we knew that it was— We had we had these pagers and then the Blackberry, which was this evolution of the pager into email and so forth. And that role of the important person, the doctor or then the executive or the governmental worker would have. You had to be connected to what was happening. That when that universalized, we would all be working, essentially laboring, all the time, which is what we’re doing. We’re not always laboring for our workplaces—often it’s for wealthy technology companies or for our own personal brands or whatnot. Or what have you.

Former Facebook VP of Growth: “I feel tremendous guilt…I think we are creating tools that are ripping apart the social fabric of how society works.” Chamath Palihapitiya, watch from 21m 20s https://t.co/TvFR8WtVrI

— Tristan Harris (@tristanharris) December 11, 2017

And like now we’re kinda going, “Oh shit.” We know now that some of the ways that even for those who were involved in creating these infrastructures, they’re kind of admitting, “Yeah, we weren’t thinking, even a little bit about the implications of what we were making.” And that’s a nice conclusion to come to after you’ve made a boatload of money and it might not matter so much anymore.

So I’ve been thinking about this whole question, this whole sort of set of ideas in the context of autonomous vehicles. And I pick them partly because I’m legitimately interested, and partly because they are so new that we’ve not yet made these errors with them. We haven’t committed in any— Either at the design level, on an urban planning level, at a personal use level. We have some runway, some blue sky to work with.

But when you look at the way even now that we’re kind of talking about this future, it’s either as this sort of like wonder—like, finally we’ll be able to rid ourselves of these awful machines that we despise. And you know, it’ll just be easy to get anywhere you want to go. You won’t have to maintain and pay for a car. That’s one of those scenarios.

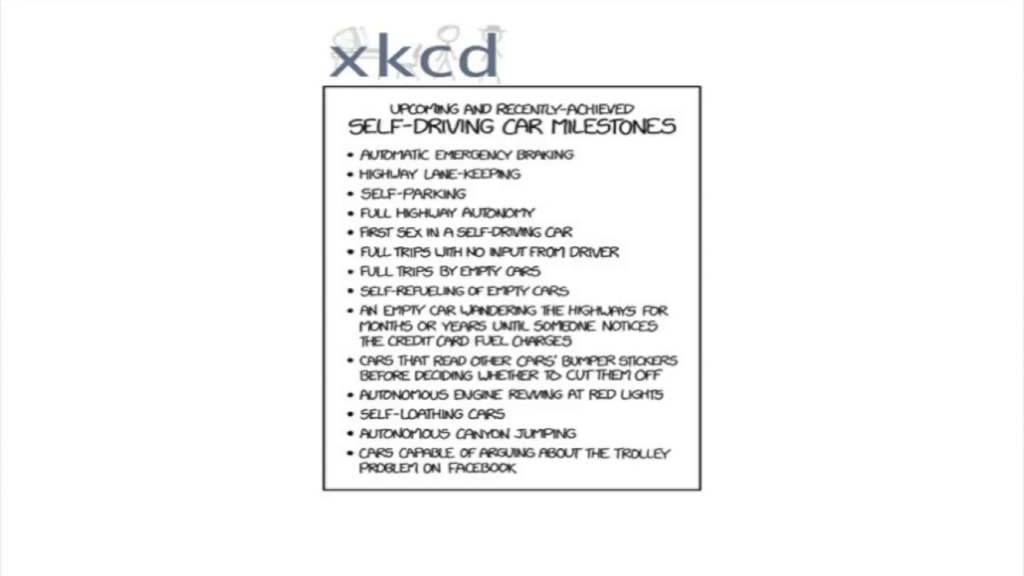

And another one of these sort of— I’m really looking forward to self-loathing cars. This is such a good comic. Or the last step in the milestones is cars capable of arguing about the trolley problem on Facebook. Like, this is funny. But it’s also a signal that— It’s a kind of cursory take on what these futures of autonomous cars might look like.

So I’ve been thinking about this for a little while. We don’t have to just talk about autonomous vehicles but I think it’s an interesting test case. And I’ve been running through a number of sort of likely scenarios in this kind of McLuhanite way. If we take this thing and we imagine pushing it to its extreme so that it really is universal, what happens? What takes place? And I’m just going to run through some notes of some of the things that seems likely to me, at universal scale, sort of when fully rolled out.

One of those is that all of the trolley problem business, like is the car going to run down pedestrians, is a very very temporary problem that has to do with this transition mode between human-driven cars and pedestrians and bicycles and so forth, and fully autonomous cars. Once you get vehicles that are fully autonomous and want to roll them out completely, then one of the likely things that will happen is that the way that roads operate will also change.

So, you can pack autonomous vehicles much closer together. You have that sort of like Minority Report vision, if you remember the tracks of Lexus-branded vehicles that are sort of swap—very high speeds, sort of swapping places with one another. These cars can coordinate with one another.

And so it’s not so much that it will be undesirable or no longer a technical problem that people or other humans driving traditional vehicles might be at risk, but it will no longer be feasible for them to even participate in that mode of conveyance. To the point that it strikes me as likely, not just possible but likely, that especially major arterials will become sort of new freeways that will be inaccessible to not just human drivers but as right of ways whatsoever for pedestrians, for cyclists. And they’ll do that because it will no longer be safe to interact with the way that the autonomous cars are behaving.

Another thing that will change is if you— I was recently in Tempe, where Uber is running one of their test markets for these autonomous cars. And they have people in them still. But even so, you realize that even if you were on the road with them, your relationship with the driver in the vehicle, as a pedestrian, as a cyclist, as another driver, is very important. You kind of know okay, I kind of have a sense of what you might do even if I can’t see your eyes because I know the possibility space of things that people do.

But we don’t understand what computers do anymore, most of the time. And the programmers of these systems often don’t understand how they work, and we get into these deep AI/ML kinds of systems, and that’s exactly what autonomous cars are. So even if you are in the same space as one of these vehicles, you’ll have no idea what its capacities are and what it might do. So you can no longer read those apparatuses—they’re no longer legible.

So you know, if you kind of run that scenario out, maybe it would just be better to take this thing that we’ve had since we’ve maintained public roads, which is the idea of the public right of way. All of us can go out to the street and use the street and it’s maintained and owned by a governmental entity, by a municipality, by a county, what have you—by a state. And they’re responsible for it, and as a result everyone has the capability of using it. Maybe that doesn’t make so much sense anymore.

And in fact it’s become very expensive to maintain American infrastructure, as we all know, and it’s kind of falling apart. And so when you have wealthy technology companies that are absolutely going to roll out autonomous vehicles as kind of Uber-style car services not as conveyances that you would buy and own and garage yourself, then just in the same way that Amazon is essentially getting these unbelievable bribes out of municipalities that want to host its new headquarters, you know maybe it’s best just to lease off those spaces to Google, to Tesla, to Uber, to whoever those players are, in order that they can kind of manage them and upgrade them to smart roads so that they can make them even more efficient.

And this might mean that— I mean it’ll start with the larger streets but then it’ll certainly bleed into smaller ones. Maybe there’ll be times when you can’t use your own road—like imagine you kind of walk out of your house and you no longer have access, or at least not direct public access, to that space.

You can even imagine a sort of blockchain-driven smart contracts kind of system where you’ve got your phone in your pocket, right, and you want to cross the street. This is like Philip K. Dick stuff, right. You just want to cross the street, and it’s fine for you to cross the street as long as there’s no vehicles in the area. You’ll just be charged a small fee invisibly when you enter into that, because it’s private property now. Or at least it’s leased off in such a way that it’s construed as private property.

Once that takes place you know, when you don’t need things like traffic lights, for example. Because those are managing human-driven vehicles and these autonomous fleets are much more efficient. Just yank out the traffic lights and they will invisibly coordinate their behavior with one another. Well when you take those sorts of things out, one of the things that comes along with them are the wayfinding devices. Street signs, street names, those are all put up for our benefit as human drivers, cyclists, pedestrians, and so forth.

And they’re quite unsightly when you think about it. Who likes to look at traffic lights or street signs? So maybe let’s just remove those as a kind of urban renewal program that could be underwritten by a company like Google. And you know, they would have a secondary interest in doing so because as it happens as you might remember, Google provides mapping services to all of us now. We don’t use paper maps anymore. And in fact there’s kind of a long history of obfuscating public space with maps that sort of are false or slightly inaccurate, or that you can control what people know. The Soviet Union has a number of examples of this that I don’t have time to go into right now.

But if that’s the case then you know, the idea that we have public access or sort of general access to maps of that might also begin to dissipate. You know, maybe there’s a service level kind of subscription to a kind of radius from yourself that you can see. Or maybe it’s just in the interest of these new public/private partnerships between municipalities and Uber and Google and so forth to just eliminate citizen use of maps because all it does is cause trouble, people go places they shouldn’t… I’m not even talking about like, the obvious amplification of kind of the history of redlining and other sorts of geographic disparities that have— We’re already seeing impacts in the way that ordinary car services work in terms of access.

We could kind of go on down on this road. And there’s a bunch of other interesting scenarios. Parking. A lot of folks have started talking about the delight that will come from the removal of parking lots, which are their own blight paved over spaces. And you know, that’s certainly likely, but it’s already happening with flat surface level parking lots, especially in dense urban centers. Those are being bought up and turned into tall luxury office and condo towers, mostly, right. They’re not mixed-used spaces really. Now you have sort of expensive condos and office spaces for companies that want to move back into the centers of cities after having spent decades on their edges.

The parking lot, though, that exist infrastructurally, that’re sort of at the bottom level sort of underground large buildings, it’s not like those are going to go away. What might happen to those? They might become staging areas for these fleet cars. That’s one thing that’s been proposed. But another thing that strikes me is I think that there’s so much more space than you would ever need to stage for autonomous car service that how might you repurpose parking decks and underground parking structures? They could sort of become new housing. Because housing is very expensive. And we have all of these workers who want to live in the center of cities now, if there are still jobs for them after automation.

But even if there aren’t, we have some signals that this is already happening. Just on the way up, I read this article. In San Francisco there are about a thousand new apartments that are being generated out of old boiler rooms and basements. So it’s about 200 square feet, which is perfectly acceptable (a hotel room isn’t much bigger than that) at a bargain price of only twenty-four hundred dollars a month, in San Francisco markets. You can imagine sort of creating these sort underground slums for workers. And this would be a benefit, really. You wouldn’t have to go out to the suburbs, because the suburbs are likely to become completely inaccessible, I think. As we see more folks move in and densify urban cores, the cars won’t even be necessary anymore. We’ll have new pedestrian and bike corridors. Think about the way that Amazon has redeveloped Seattle, the sort of South Lake Union area of Seattle, and that sort of thing seems increasingly likely.

So if you’re wealthy enough to live in the city center, you probably won’t be bothered by autonomous cars at all and maybe we’ll see a shift into these sort of autonomous buses that ship people back out to the suburbs and the exurbs. And then once you’re out there if you don’t have a car anymore you’re completely screwed. What’re you going to do? So you’ll be kind of under house arrest in those spaces, or maybe maybe we’ll develop these kind of like, illegal human-driven taxi services that will crop up. And that’s not even to mention what happens to folks in rural areas once they can’t get access to electric or internal combustion engine vehicles if they’re taken offline.

I also thunk about garages, about all of the in-town, not suburban but kind of urban single-family garages that exist all over America, which would no longer be necessary, really. You’re not going to own these vehicles. And so if you’re lucky enough already to own a property like that, then you’ve got a kind of built-in Airbnb. So like there’s some kind of mass conversion. And there will obviously be a kind of classist relationship with people who are renting out these converted garage spaces. Not to mention the fact that it only amplifies kind of existing wealth inequality as we’ve built so much of our wealth in America for the everyperson around property ownership.

Anyway, there’s like you know, dozens of these kinds of scenarios that we could spin out. I may be right or wrong. It doesn’t really matter in some ways. It’s rather that if we sort of shift from thinking about the technology and the near-term problems to these kind of medium to long-term scenarios that assume adoption at a universal scale—just to ask questions about them—then that sort of scenario, which you know, bears some relationship to science fiction, some relationship to like, RAND-style scenario planning, some relationship to other kinds of futurism but I think is still distinct from them. Because it’s asking questions about like, what is the current technology going to be when it flips its bit, when it reverses. Because that could still be changed as we’re working in the present.

So those are some thoughts. That’s sort of what I came with.

Schnapp: Yeah, no. I mean, I think that’s a great launchpad for this conversation. And I guess I’d be interested in starting out the discussion part of this. And Ian and I agreed early on that we very much want to involve the whole audience here as part of this conversation. But I thought Ian maybe as a prompt since you introduced Kant into the conversation right from the get-go—

Bogost: Sorry for that.

Schnapp: —and your own training has this really rich and interesting sort of crossover between philosophy, theory, critique, and practice, and [indistinct]—

Bogost: Yeah.

Schnapp: —that if maybe we could talk a little bit about pessimism as a stance. Because of course in these various tetrads that you wonderfully brought up from the McLuhan era of media theory…you know, pessimism itself is often not pessimistic.

Bogost: Right.

Schnapp: Rather it is an intervention in an emerging set of debates, of concerns, of forces that run in different directions. I mean, certainly for Nietzsche, pessimism…and for a whole strand of philosophical critique, pessimism is the corrective. And in the case of autonomy, and I think you wonderfully spun out some of the potential ramifications of an autonomization of the world.

But of course the question in the word autonomy that…coming from a philosophical background would immediately introduce is of course autonomy for whom? Like, who gets to be autonomous? In the service of what values? I mean, all of these various scenarios that you described, from these worker colonies, or maybe encampments in the exurbs, of disenfranchised a populations. They all raise this question. Who gets to be the driver in the place of the driver, so to speak. Whether it’s the level of social forces, or the architects of cities, or who owns the public spaces—what is a public space?

So I guess I’m just curious given the extraordinary range of your own work, how you see this kind of critical intervention in shaping that future conversation about the design of cities. Because we’re just at the beginning of that. I mean, I think as you suggested, this is a little bit different than some of the other cases that we started with.

Bogost: Right, right, right. So one thought I have about that is that when you bring… When we think about the interaction between technologists and philosophers, it’s a sort of smarmy conversation we have about that interaction, right. Like, [mockingly] “The humanities are still important. We’ll bring in these philosophers who’ll help lead us—”

It’s like um, really? That’s all we can muster, is this sort smarmy appeal to like, ethics and you know. Which isn’t to say that it’s a bad thing to think about the moral implications. But I actually think it’s a mistake, it’s like almost a category error to take these kinds of scenarios as just moral implications. They are in some ways metaphysical implications, right. Like, ontological implications. We made this thing—it was blogs, it was the Internet, it was smartphones, it was autonomous vehicles. Whatever it is. And you know, everyone has the best intentions, or at least something that’s not the worst intentions. They had some good intentions. And then things got away from us, right. It took on a life of its own. And the best conclusion we seem to come to, once those outcomes are unexpected is, “Oh well. This just once again proves that technology is neither positive nor negative nor neutral,” right?

Okay, great. And then we’re just left with the results. And then we just kind of like, move on to the next thing as thought nothing happened, “Oh…let’s kinda wash our hands of it.” So to me, one way of getting at that answer is that… You know, design is the space that sits between technology and philosophy? And unfortunately design has also sort of been troubled in recent years as the sort of design thinking nonsense has taken over all conversations. You know, what does it mean? Well it means…just basically…speculative finance, right. Like everything, right. Design thinking is kind of speculative finance, like technology is kind of speculative finance. The philosophers haven’t yet gotten around to casting their work as speculative finance, so…

Schnapp: That’ll come, though.

Bogost: Maybe, well…probably won’t come.

Anyway, so design is this space where we muster abstraction and make it concrete. And then it gets pushed out into the world through a implementation. So I’m interested in that community or that mode of thinking as one where you could begin asking questions instead of about use, or about outcomes, or about these sort of moral or social implications, all of these kind of smarmy frames that we draw around things, and that frankly, the folks who are making these technologies aren’t that interested in hearing, and transform that into questions about the essence of these products or services or objects.

Schnapp: So just to jump in, though, in the case of your work on game design, for example, the use of interactive game platforms as spaces of critique or critical engagement of some form. Would you see an analogous extension out into the sphere of, sort of get in under the hood and make or tweak or [crosstalk] hack technologies that involve—

Bogost: Yeah, right. I mean. Well there was this— When I start working in games, you know, and I did all this work with kind of games and politics and education, and you know I had this whole argument, this sort of like 150 thousand-word-long [indistinct]. I built a whole game studio around the idea that we could take the way that things behave…you know, these systems of behavior, these complex systems of behavior in the world. And because we have the capacity with software systems like games to depict those systems, systemically, in representational form, that we would be able to understand them, critique them, maybe make alterations or claims about them more easily. And that works in theory, on paper. But what I didn’t think about at the time, you know, ten-plus years ago, fifteen years ago when I was working on this, is that those media objects and that whole design philosophy exists in a media ecosystem with everything else.

So, if you zoom back and you kind of imagine okay, it’s not just that we’re kind of making these representations of how things work rather than depicting and describing them, but then we’re also trying to alter the media landscape such that people are looking for understanding and conversing about those kinds of systems, that’s what would be necessary. And of course that’s not what happened at all. We don’t talk about like software model… You don’t wake up in the morning and open your phone and look at the latest software model depiction of the current state of climate or politics, right. You read text, you look at images, you watch videos, you listen to audio. It’s just the 20th century. 20th century forever.

And so the two lessons I would draw in answer to your question is that on the one hand it’s the same interests, right, this idea that there’s sort of deep structure in things. Essence is very unpopular, right. No one likes to talk about it. They like to talk about transformation and change and becoming. But no, there’s something about essence, about deep structure, that seems endemic to grasping something. Which is one of the reasons why the McLuhans are of interest to me.

But then also that I made that very category error that I’m talking about, here, today, which is that I thought that this was a design problem that was unrelated to other design problems in the media eco—or not even design problems, just sort of trends and flows. And now I mean, I really do believe that that opportunity is…like that timeline has been snipped. We don’t know what it would be like to go down it any longer.

Schnapp: Great. Well, I’m gonna open up the floor here for just people to jump in. Daniel, are you going around with mics? Yeah. So if you would like to join the conversation, just raise your hand and Daniel will come over.

Audience 1: Great talk, by the way. I have a couple of questions but I’m going to ask one of them and then you can tell me where it goes. First, I mean, is it pessimism or is it creative destruction? I mean that’s an economic term I guess, as against a philosophical, right? Economic philosophy.

Bogost: Yeah. Well I mean, so the economic position is that it doesn’t matter what happens so long as there continues to be musterable productivity. So long as there can be an economic machine that continues running. Whereas pessimism says things are bad and they’re getting worse.

Audience 1: Right.

Bogost: So if the way that you measure goodness is through economic value, then so long as economic value continues to increase and so long as it increases for the agents for whom you think it’s important that it increases then you’re fine. It’s all good. There’s only optimism.

And you know, it’s arguable that this position is the strongest one, right. That even the optimism/pessimism dyad is just a foil for a true interest in continued economic productivity for a selectively smaller and smaller group. And you know, I don’t think we can just dismiss that idea and say well obviously we don’t want to go down that road. Because in fact that’s the road we’ve been on for you know, a long time.

But if you take—the interesting thing about the pessimist as like a sort of figure to embody, right, is that it’s this…you have a—it’s like putting on a hat that says “I’m just gonna ask what’s the worst case,” you know, what’s the worst possible scenario. Not because you’re some sort of a masochist. Or really a pessimist in the pessimists sense, everything is going to hell. But rather that posing that question, even from the vantage point of economic development, right, would allow you to see possible scenarios that you would otherwise miss.

The interesting thing about the way that technology has been proceeding, even on the economic register, is that without asking any questions whatsoever, it seems to be working out, right. Through accident rather than a sort of creative destruction kind of sub—through mostly dumb luck. And then a kind of amplification of those scenarios, especially as Internet-based services have globalized and they’ll sort of reamplify the difficulty of finding new answers, of intervening in these systems.

So, I’ll give you one example which is probably on people’s minds lately, which is this net neutrality conversation, right. So…I mean…I don’t even know if I want to touch this subject in this room.

Schnapp: It’s dangerous.

Bogost: Well look, common carriage makes sen— It makes sense for broadband and wireless data to be treated as common carriage. But at the same time, the Internet is kind of garbage, and something that might change it in any way is worth at least talking about. At least talking about, right. But you can’t even really do that. You kinda say, “Well let’s just like step back—” and you get yelled at on Twitter or whatever by the throngs of… I don’t even know what their position is. Like there’s lefties, there’s sort of these centrist libertarianism that have the same—it’s kind of all over the map.

So we’ve worked ourselves into a corner with a lot of these questions, where we can’t even really pose interesting questions about them. And one of the reasons we can’t is because we’re stuck within these systems that we’re supposedly preserving, by means of taking on an obvious position like we wanna make sure at all costs that net neutrality doesn’t disturb the sanctity of the Internet—which we also believe is garbage and now we have convincing evidence has had real negative implications on civic life and so forth.

So yeah I mean, I think that’s the interesting thing about wearing the pessimist hat. It’s a license to sort of say okay, what is awful, or what might go wrong, and let me at least think about that for five minutes even then I’m going to sort of shed it, take it off and come back to reality.

Audience 1: And just one follow-up thought experiment, right. So, if we were sitting—I’m in Buffalo, New York where I work—and we had an analogous event, right, 150 years ago, we tried to build the Erie Canal. Which was kind of like a huge evolutionary leap. We were trying to build a canal that would make boats go from Buffalo to New York City. But then as they started developing this high-tech event, infrastructure project, trains came in.

Bogost: Yeah.

Audience 1: Killed the canal. Just when the trains done, highways came in. Killed the trains. We can see the same, you know—

Bogost: Now it happens a lot faster.

Audience 1: It happened with cable TV and network TV, right. We see that evolutionary process and I wonder if we were sitting in a room back then, would we be pessimists fighting that process with that same view? Is it just history repeating itself with a new set of technologies? That’s the only other question.

Audience 2: Hello. Sarah had mentioned going and that I would really enjoy this talk. And she…was right. This is all I think about all the time. Something that really stuck out to me was earlier when you were talking on the blog example where there was so much promise and you know, you talk about how much excitement there was around it. And I’m a technologist. I work at large tech companies. And when I think of every product launch, it’s just like people are on stage talking about how cool it is that at any point in time you can tell someone it takes fifteen minutes to get home. And you don’t really think about the kind of data that takes or what that means for someone’s privacy, etc.

And you mentioned also that when people build stuff, they have good intentions. And if anything when I’m around here I actually often hear the narrative that the Bay Area, Silicon Valley is only profit-hungry and everyone cares about money, and that they actually don’t have good intentions and they’re evil. And so my question is, as I think about how to really shift the tides of my field, is it that people are profit-hungry and evil, and that’s like the real narrative? Or, is everyone actually just like way too optimistic and only wants good things, and that’s the blind side. And which side do you think it really lands on…?

Bogost: That’s a great point.

Audience 2: And how do we like, change it?

Bogost: The short answer I will give you is I think the vast majority of people are blind optimists. They’re not power or wealth-hungry extractionists or something. There are some of those. And one of the interesting features of the tech elite is that it’s a particularly odious kind of power and wealth hunger not because it’s different from other kinds of business or from finance, which is I think the ultimate sort of reference point. But because it’s dishonest about the power and wealth hunger, right. You talk to a hedgie and they’re not going to be like, “I’m trying to change the world,” right. They’re just like, straight up about it, right. Whereas you talk to a tech VC or CEO and they will feed you that line, whether it’s true or false. And you look at the behavior of a company like Uber and it’s pretty cons—it’s not all companies, right, but it’s kind of clear where they’re—

But then the folks who are the line workers, basically, they really are… Well first they’re just trying to make a living. And these are basically middle-class jobs at this point in the sectors where tech is flourishing. And also they have the best intentions. They do.

They’re also on the ground, you know. And there’s a certain amount of power that they have. But also I think that that sort of whole modality of optimism, whether it’s truthful or false, right…has so…we’re just drunk on it, you know. Like nothing can go wrong. And now that we have evidence that actually things kinda can go wrong, we weren’t just kidding ourselves about that, there’s an opening to say okay like, if we can stop in our kind of daily…on a pragmatic level, the daily, weekly processes of building these products and services and start asking okay so what happens… We’re going to roll this little test out of this product. What happens when everyone in the world is using it, what does that look like? And then you know, do we want to sort of backtrack from it at the design level.

You could also introduce… People talk about regulation and other forms of external control as being important—and they are, I think that’s another missing bit to this. But we’ve also kinda gone off the rails with regulatory management of everything. So it’s a pipe dream to think that will suddenly like come online. Although it is interesting that the one thing that seems to have revitalized itself in the Trump era is corporate antitrust, which the eight years of Obama, the kind of cool dad social media president and you know, none of that was happening.

So you know, in other words I think a purely regulatory answer is probably not going to come about. And so unless we get inside the ordinary everyday worker, we have no hope of averting disasters of the future.

Schnapp: Just to jump in on your question isn’t also one of the expressions of pessimism better design practice? A better, a more widely-informed…uh…

Bogost: Yeah. You know and…also like a slower design practice. I mean, this business of speed is not just a matter of the increasing the speed of change in business and culture. It’s also the speed of product and service development, and deployment? And we’ve celebrated that for a long time. And it allows us to do these experiments and make these changes and we feel like we’re not hurting anyone in so doing, but it’s clear that actually no, we are hurting people in so doing. And you know, how do you dampen that? One of my hobby horses that’s a little bit orthogonal to this talk but is still relevant is the— So, folks in computing call themselves “software engineers,” but they’ve never adopted the orientation of civil service that the engineering professions did, through professional engineering certification but also through just a kind of professional ethos, which is not that different from the way like journalists think about their work. And so it doesn’t all have to come from outside or from sort of like tight regulatory control. But yeah, slowing things down might also help.

Schnapp: Mm. Interesting.

Audience 3: Hi. Thank you for the glorious talk, and I really do think it was glorious. But I want to challenge its label as pessimism, because what I hear is an optimism that there will still be a civilization that will be making progress for at least somebody, or some small group. And you know, you mentioned Philip K. Dick and you know, when I think autonomous vehicles in the current structure I go full Philip Dick and think of you know, fleets of abandon—or packs of abandoned autonomous vehicles wandering abandoned hulks of cities—

Bogost: Right.

Audience 3: —as the rest of us are going all Mad Max or The Walking Dead trying to reinvent how you make bullets or something. So I guess my question is why are you such an optimist? [laughter]

Bogost: No you’re totally right. The pessimism sales pitch was just a lie to get you to come. Yeah.

Audience 4: Actually I had a similar question, which was you know, your net neutrality example made me think that you could frame being pro net neutrality as a lack of pessimism about net neutrality means, or a lack of optimism about what deregulation could lead to. So I’m wondering why you choose to frame it as pessimism rather than skepticism, just challenging your beliefs whatever they are. And I wonder is that because you think that in the realm of technology we have an inherent bias towards being more willing to believe our positive self-deception than our negative self-deception?

Bogost: That’s a good question I don’t know…I have to think about that and I will think about many times in the near future. I think my gut reaction is that for many years, pessimism was off the table. The moment you started making critical comments about contemporary technology you were either a Luddite, you were just an obstructionist, you’re blinkered, you didn’t understand. And maybe the only good thing that’s happened in the last year or two is that that preconception has been stripped away and now okay no, maybe we ought to be more critical. But I don’t think like, being critical or skepticism…it’s it’s too modulated, it’s too modest and moderate. And we need a counterpoint to that extreme optimism that we’ve suffered under for so long. So maybe if we go full pessimism for a while, knowing that it’s extreme, that it’s too much, then we can sort of find some reasonable space in the middle.

And this is maybe not that different from any sort of polarity that we might be experiencing today, in politics and in social issues, where you know, the moment that you try to modulate in the middle you actually end up just being pulled to whatever extreme is acting in the most extreme way. So like it or not we have to respond to that, maybe excessively.

Audience 5: So, you mentioned at one point snipping off lines. It feels to me like we’re right now living in an edge effect time? And how do you get out of that?

Bogost: Yeah, well one of the amazing things about the arrow of time is that we don’t know what the alternatives might be. And so you know, traditionally science fiction, speculative fiction, or these sort of speculative design concepts that borrow from that premise but for built objects or the built environment, one of the interesting things about those traditions is that they ask questions about what could be, but typically its allegorical. It’s actually about the present. Whereas it could also be about loss—there’s sort of historical fiction or other ways of thinking about lost presents from alternate futures of our actual past, right.

And then there are the alternate futures of our actual present, which is not what traditionally science fiction does. And so if you muster those objects or those traditions or trends, whatever, modes as tools, deliberately, in a way that doesn’t like, I don’t know, throw them into the cultural abyss of sci-fi. Which is a problem. Or, simply kind of turn them back into these allegories of the present couched as the future. I think that’s one possible tactic. It’s certainly not the only one and it probably is insufficient but it’s one that I think about a lot, that if we can just sort of open our eyes to this string theoretical impossibility of all of the possible futures that we right now sit at the intersection of, and we can think of them as possible actual futures, then we could design toward them rather than just like “I dunno, we’ll just do whatever,” you know. Like whatever happens, fine, because we did it. And then we meant to and then you kind of tell the story of how you really meant to. Then that kind of planning…it will look like planning at that point, right.

Audience 5: Just a follow-up. So I read alternate history a lot. I look at that. I think about Kim Stanley Robinson has some great climate future histories. I can think that way, but how do we get the whole electorate to think that way?

Bogost: Yeah, when you’re not—

Audience 5: And that’s like our big problem right now. It doesn’t.

Bogost: Yeah. I mean you know, like the whole electorate is probably not a good target market for much of anything?

Audience 5: A majority.

Bogost: Well, I mean, think about where change happens. It doesn’t happen from the will of the people, even though they often get to vote—at least in theory—on these things. It happens at nodes of power and influence. And so if we can change those, then we might actually have more influence on that collective, rather than going to them at the grassroots.

Sara Watson: So, following up on that a little bit—Sara Watson—I’ve been thinking a lot about the kind of trajectory of how these pessimistic or critical conversations have been happening but also how they’ve changed over time. And I’m wondering…you know, even over the last two years, thinking about the worst-case scenario, plenty of people have talked about like the worst-case of Facebook, or you know, kind of that… And yet, nothing happened or nothing was possible to happen until a real worst-case scenario actually happened, Russian interference being one of these—

Bogost: Yeah, we were talking about exactly this thing in the last election cycle.

Watson: Right. But like it took the worst-case thing to actually happen for anything… For a scale of people to actually care and for people to actually respond and change things. So, to that end like, where is that line and what is the effect or how do you think about influence when it takes that kind of worst-case example.

Bogost: Yeah. I mean— So either we’re… You know, what are the possibilities? We’re idiots. We were unpersuasive. It was not important. It was too seductive and no one could see the alternatives, because they couldn’t feel them—they were abstract. It’s possible that even though it seemed like people are just very bad at future planning. And so it seemed even plausible? But that plausibility didn’t seem near enough in time to be actionable. And I’m sure there are dozens of other possible cases that we could run.

But now we’ve ma—like…that’s done. And you know, these sort of small trend tab adjustments that Facebook for example is making are probably not that important. So giving up on that and moving on to something else is one possible answer. I guess what I’m trying to say is that we have to start acting incredibly tactically. And that is not something that for example the political left in America, or the sort of technology-friendly, counter, cyberlibertarian community is very good at doing. It’s just all idealism, you know. And so moving back into tactics, the sort of very pragmatic realpolitik of this might be one answer.

Watson: Well and that gets to the question of audience, right. Like to which audiences are you actually forming these interventions or reframings or whatever.

Bogost: Yeah. Right. Right. Like lets say you were to embrace just buying the solutions, right. So we need a sort of Koch Brothers for the left or something. Like you know, there are plenty of billionaires who are empathetic to this. But they are not going about using their money for influence in the same way, right. It’s not as aggressive. I don’t know how you convince folks like that to do so. But instead they like buy media companies and have like hobby newspapers or magazines or something like that.

Schnapp: I’m curious, Ian, in the context of answering Sara’s question you brought up the notion of persuasion as a kind of core problem. Like where and how…and of persuasion is the object of rhetoric, which is the most venerable theory of communication in the…certainly Western cultural tradition. And in your gaming work, persuasion has also been a key issue. I guess I’m wondering with respect to the question that Sara was asking, also the prior question, where and how does persuasion happen and become efficacious in a kind of media space, a media ecology like the one we inhabit today.

Bogost: Right. I mean, so the rhetorician—the good rhetorician, whether it’s a Burkean or an Aristotelian, has some understanding and respect for their audience, and acknowledges that audience. And that may be the biggest missing bit if I had to pick one.

Schnapp: Yeah.

Bogost: And you know, there’s reasons for it. But without sort of understanding and coming to…you know, it’s not meeting them half-way it’s like meeting that audience almost all the way, maybe even more than all the way, in order to then make an appeal of some kind. And in some ways these systems sort of reinforce the bad habits that draw us further and further away. Like one of things we talk about a lot at The Atlantic and in media in general these days is the sort of problem of the “coastal media elites” you know, the “fake news media environment” that Trump and others have successfully antagonized. Which was and remains an actual problem. You know, you live in New York, or DC, or San Francisco or Los Angeles or wherever it is that media gets made, and then occasionally you drop ship a couple folks into Ohio to do some sort of…it’s almost like this sort of like colonialist affair, right. Oh look at the strange behavior of middle America.

Schnapp: Natives.

Bogost: So you know, people are reacting negatively to that for a reason. It’s continuing. You know, The New York Times is particularly expert at this even in light of everything.

So that’s just one example, but I think maybe that’s the most important bit. And I don’t feel like I’m good at this yet. And so I feel sensitive about calling it out as a bad habit. But maybe that’s the big one. Like what are people encountering and experiencing. One reason we missed the Facebook stuff is people love Facebook. They love it. People love Google too. It allows them to do things that feel magical and that give them immediate and enormous value.

Watson: But what was like the best-case version of that? Like influencing engineers to change things, or…

Bogost: Yeah. I mean, if we run these scenarios on the immediate past, we could probably in hindsight come up with some likely scenarios that might have averted certain kinds of effects that we might construe as negative and that others might not. But I don’t know if that’s where we want to spend our time. It’s an interesting affair. Maybe someone should be involved in thinking through that as a way to move us into the present. I’m not trying to be ahistorical here, even though it’s hard to even call this…we’re talking about like two years ago, you know.

Schnapp: Yeah, exactly. What counts as history today.

Bogost: But because of this speed business, the urgency of the near future suggests that maybe we don’t need to answer that question.

Moira Weigel: Moira Weigel. Thanks so much for your talk. I wanted to ask, following up on the stuff about politics and tactics, what is the significance of that split you alluded to between VCs and management and engineers, and sort of rank and file tech workers. Because it seems to me that that’s become…I think both because as a result of the election and the sort of tech CEOs meeting with Trump after the election, and the increased material pressures of living in a place like the Bay Area, the reality that for the most part tech workers are labor and not capital. Or whatever, you know, the idea that they’re not…that most tech workers will never be VCS or—

Bogost: Yeah. Well they’re not capital owners.

Weigel: Right. That’s the—

Bogost: Even though they might appear to be because they have stock options or whatever.

Weigel: And so I wanted to ask in terms of politics and tactics and strategy what do you see as you know, in terms of thinking about civic responsibility or resisting the Philip K. Dick future. Like what’s the significance of that split.

Bogost: Yeah. It’s… [sighs] I guess the observations I have is that when outsiders make this claim, whether it’s journalists or scholars or even folks who’re sort of…you know…inside of the tech world but not necessarily in a…kind of what I’m calling a line worker capacity, to kind of emphasize that, they don’t seem credible for some reason, right. And also that crop of labor is very inaccessible. They make themselves inaccessible and they’re very tightly controlled by their organizations. So actually it would be really hard to do a sort of on-the-ground investigative report of worker life at Google.

And there’s there’s all sorts of reasons for it. So when we do see little bits and pieces of it, it’s usually through financial or business news. Just just this week in fact, there was an interesting little kind of exhaust emitted of the world that you’re drawing attention to, where Uber workers who hold options are trying to unload them in order that they can turn them liquid. But unless there’s a certain amount, because it’s all going through like SoftBank or something, then there’s this option to do a certain amount of—but then you have to also be registered in the right way to be able to transact. And there’s all these kind of strange secondary markets for financial instruments these days.

So that’s where that reaches the surface. It’s all about money. And no one like…like, how do you sell that to— You know okay, what you’re living on you know $250,000 a year in San Francisco and you have all these stock options, you want me to…empathize with that? And this is back to the business of audience, actually. So for the tech laborer to appear as a laborer like any other kind of laborer does, something will have to bring them together as a group and create a kind of equivalence between their plight and the plight of “ordinary people,” right. I don’t know how I would go about doing that. But again, it’s a tactical question rather than a sort of question of ideals. I hear these stories all the time. People talk to me privately about them constantly.

Weigel: And there is a group at least in San Francisco that has a chapter here that like helped with the Facebook cafeteria workers unionizing and stuff—

Bogost: Yeah, but it’s always those kinda workers, right?

Weigel: I know, and they go to the contract workers, they all get fired.

Bogost: People know about, you know the Filipinos scrubbing data, and people know about the cafeteria workers. We’ve seen— And that’s because of this sort of New York Times effect, too. Like that’s the story that appears to be bringing the plight of the downtrodden to light. But it’s just unseemly to say well yeah, I mean, there are these six-figure-earning knowledge workers who are also the downtrodden. That story is just not gonna fly. How do we tell that story in a way that will?

Audience 8: This may go back a little bit before you were born, but in ’67 a Harvard economist, John Kenneth Galbraith, published a book called The New Industrial State. And it’s a little simplification, but his main thesis was that perhaps the markets aren’t so good allocators of capital, and you should have some kind of local deity that says basically where will capital go, what will be developed. And Galbraith was around six-six, very tall. He looked around and couldn’t find any local deity but himself, so he— [laughter] I’m an MIT economist, so I’m not gonna say that. It’s true.

So my question is then, given your observations and thinking even of plowshares—what we talked about when nuclear power was invented and how it would turn the swords into plowshares, something for good, how do we proceed to get the good out of technology and stop the evils?

Bogost: I did this piece for The Atlantic…I don’t know, a few months back, about this kind of unassuming a New Zealander guy who lives mostly in a boat. And he’s in and out of network access, right. He’s disconnected from the normal infrastruc—not to mention that down in that part of the world they’re already disconnec—it’s already difficult to get data of any kind in Australia and New Zealand. One of the great observations he made to me is there’s a reason rsync was invented in Australia. Just the infrastructure of a connectivity, even fiber, is not such that it was reliable enough.

So anyway, he has been sort of reconstructing the same kinds of social media kind of tools, the same kind of consumer-facing tools that we use at a global scale at this distributed local scale. It was a really interesting a set of examples because it was like well, maybe the problem isn’t in the product design itself but in the idea that all information should be globalized and all access should be globalized. And if you kind of stop and think for a second about the encounters that you have on a day-to-day basis that are bad, where these atrocities start to sort of bubble up, it’s often because you want to be working at a…maybe not a local level, maybe a local level, but at least not at a global level, and you just cannot anymore. Everything is immediately globalized.

So this isn’t like, a sufficient answer to your question. But it’s one example of an intervention that you know, okay, it’s still experimental. It’s hardly widespread. But I can kind of imagine folks adopting, you start to see it happen. And there are places where there are examples at scale that are good and bad. I mean, there’s this lovely/awful social media service called Nextdoor? Which is you know, mostly people complaining—mostly people demonstrating that they are in fact racists. Or like complaining about dog poo. All the stuff that, you know— But as someone who’s—I’m like very involved in local land use politics in my community. And that’s a hard sell to anyone, but actually through an example like that which is globalized, so you sign up for this service but then it gets localized down to your kind of neighborhood or the nearby area, you start to see more kind of productive, positive…or at least functional outcomes take place, even though the story that people like to tell is you know, how racist everyone on Nextdoor is, or how they just comp— There’s a parody account on Twitter that’s hilarious, throwing all the ridiculous things people say.

But now you can in fact borrow a planer from someone down the block, or kind of talk about whatever local school issue is going on. And that sort of small-scale intervention seems like people have given up on that, almost. Like well, why even bother. But the sort of “all politics are local” aphorism is aphoristic for a reason.

So I think you know, in summary, if we have a bunch of these experiments that are not aspiring towards singular answers for everyone that are all billion-plus-dollar companies that take over some entire sector, that would be a good start.

Shnapp: What about, just since you were focusing on a kind of new model of localism. What about the pace issue?

Bogost: Yeah.

Schnapp: Are there…you know, ways of slowing down, or creating that framework that allows for a different way of modeling, of build platforms of…yeah.

Bogost: I mean, I think locality is one way into slowness, actually. So just the quantity of stuff you have to deal with. Like think about all the things that happen in the world every day. And now think about all the things that happen within your sort of extended global community every day. And then zoom all the way down to your block, or your floor, or whatever. And there’s just far fewer things that happen at the local scale. And one of the reasons that many ordinary people appreciate and enjoy a platform like Facebook is that unlike us, unlike people who are in a room like this, they are mostly using it as a local conversation tool with a small group of people. And then they’re extending that to a kind of global phenomenon, but that’s not the global phenomenon everyone encounters.

So, you know, the idea that we will slow down is not gonna… It’s not oh, let’s just kinda pull the plug on this. And you can imagine these sort of experimental…you know like…Oulipian sorts of constraints applied to these services that we use. But that’s just like an indulgence of the elites to even ponder, right. So we have to get at them sideways, through other means.

But, at the same time you know, regulation is one of the things that slows companies down. There was great peace recently about how Uber is in essence a regulatory arbitrage company. And so you know, if your core business is regulatory arbitrage, then kind of the more confusion you can throw at the apparatus while you’re trying to work out the rest, would work out. Of course enforcing regulation at the local and national level would be another way of going about it.

But I think those answers, again they’re just all like super weird, very tactical, very boring…like they’re not the kinds of things that ring of this kind of like, “I found the answer,” that we’re used to hearing from tech and that we give an audience to.

Schnapp: Alright, well thank you very much everybody. Thank you Ian, especially.