Addie Wageknecht: Hey, everyone. What’s up? I’m Addie Wageknecht. I founded a group called Deep Lab, and this is…

Jillian York: I’m Jillian York, and I’m a member of Deep Lab and also the Director for International Freedom of Expression at EFF, the Electronic Frontier Foundation.

So, what we’re talking about today is how social media, and specifically Facebook because we’ve found that they have the strictest policies around this topic, how these social media companies censor art, and specifically nude art. We believe that nude art is an important part of our culture, an important part of our history, and an important part of our present.

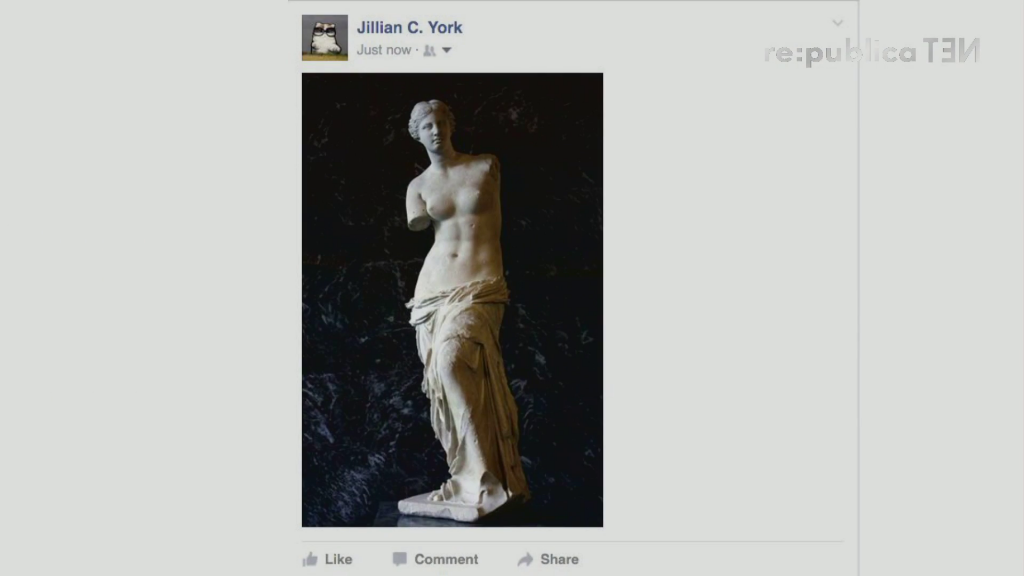

So, this piece, just as an example, is something that I successfully posted on Facebook just a few days ago. Now, of course because this is Venus de Milo, this is a famous sculpture accepted throughout the world as high art. Therefore, Facebook thinks that it’s okay for you to post this.

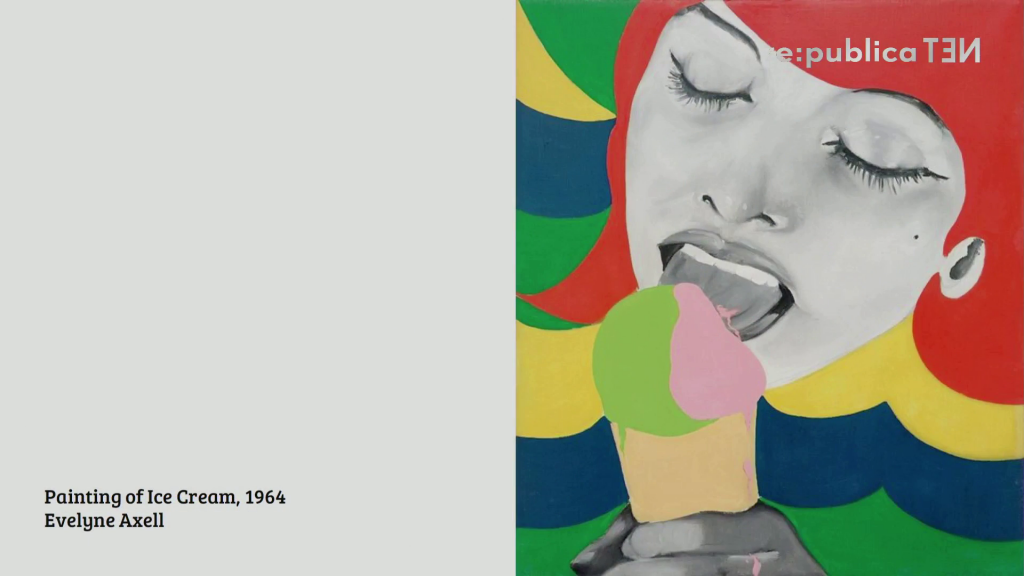

Evelyne Axell, “Ice Cream”

Wageknecht: So, a good counter-example of this is a piece that was published on February 2016 by the Philadelphia Museum of Art. It’s a piece that was on exhibition during a Pop Art exhibition and retrospective. This piece was banned and deleted off of Facebook, they said due to the “excessive amount of skin.”

York: So, we found that that was a painting that was too sexy for Facebook, but…

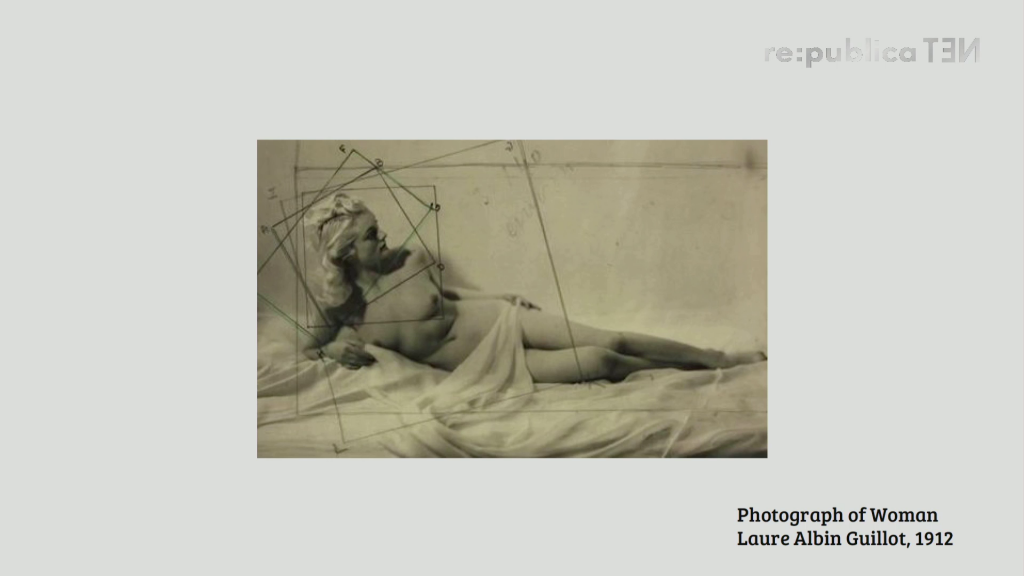

Wageknecht: So, this is another one again, just to give you an example of what’s being blocked. This is from the Centre Pompidou. They had a retrospective of this female photographer. And because the nipples were shown, the piece was removed, as well as the community. It was actually the second time the museum has had a ban. And they left a note after they were re-released in the community after twenty-four hours that they said, “We will not publish nudes in the future.”

We remove photographs of people displaying genitals or focusing in on fully exposed buttocks. We also restrict some images of female breasts if they include the nipple, but we always allow photos of women actively engaged in breastfeeding or showing breasts with post-mastectomy scarring.

Facebook Community Standards [presentation slide]

York: So, what is a nude, and what is a n00d? Well, Facebook says that they remove photographs of people displaying genitals or focusing in on fully exposed buttocks. They also restrict some images of female breasts, if they include the nipple. But, they say “we always allow photos of women actively engaged in breastfeeding or showing breasts with post-mastectomy scarring.

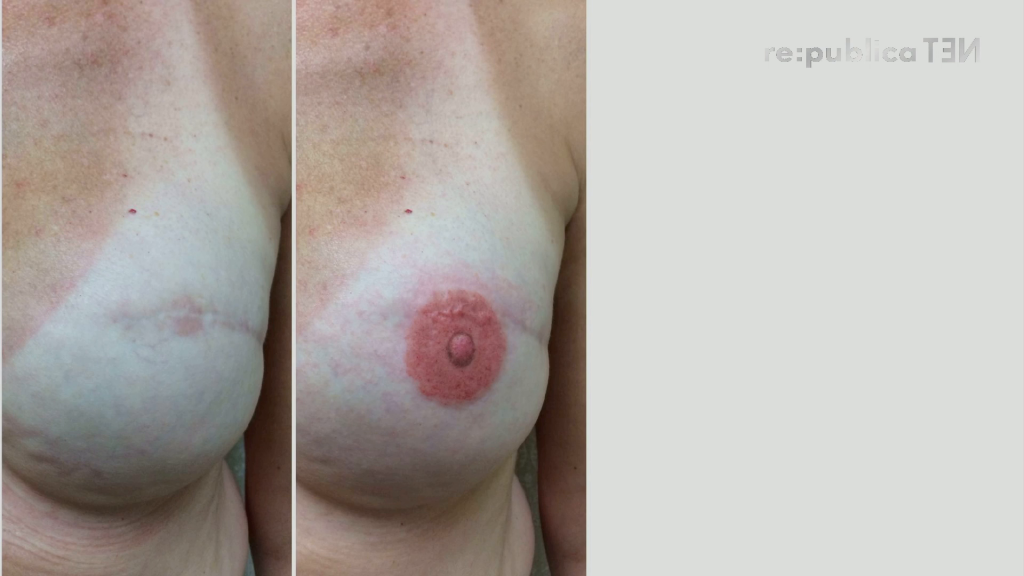

Okay. So they’ve laid out the rules clearly, and they told us what we can and we cannot post. Except…they’re lying. Because here is an image by a tattoo artist, Amy Black.

Tattoo by Amy Black

The tattoo and the photograph are both by her. Now, Amy Black, she’s incredible. She does tattoos for women who’ve had mastectomies. So, she’ll do whatever you like. I’ve seen one that’s a beautiful grapevine crossing where the scars were, and across them and around them. But this is a photorealistic tattoo of a nipple that she did for a woman who’d had a mastectomy. Amy Black has found that her content is regularly taken down from Facebook. Other communities, as well her, that post it have received bans from the web site from twenty-four hours to thirty days, depending on the content that they post and how many previous offenses they’ve had.

And I’ll get to the bans a little bit later, because there’s some more interesting things there, but I think that this is a really good example of how the rules don’t really actually matter, even after they’ve been spelled out.

From “Breastfeeding” series, by Jane Beall

Wageknecht: So, again this is another example of a photographer who did a project and wanted to start a community for women to accept their bodies post-pregnancy and post-partum. It was specifically around breastfeeding and the act of breastfeeding. She established this community. It received multiple hate mails from people within the community, and was ultimately taken down by Facebook as a whole.

Another similar example is an artist named Petra Collins, who works primarily on Instagram. She had images removed that were not of rape or violence or hate, but rather pubic hair, because she showed a picture of herself in a bikini where she hadn’t properly waxed, and they took this down.

What’s interesting to think about is kind of the contrast and the dichotomy that you look at when you see people like for example Justin Bieber, who’s a major movie— Well, not movie star…

York: Singer.

Wageknecht: Singer…? In the States.

York: We know who he is.

Wageknecht: That guy. So, he did a campaign for Calvin Klein. The ads were put all over New York City, major billboards, online, but with the difference that they actually Photoshopped the pubic hair in. So, again it comes down to this relationship women have with their bodies and what is considered acceptable or not acceptable, based off of these corporate censorship rules and norms.

York: And these rules certainly affect women disproportionately, as well as transgender people, and other people who fit outside of the gender norm, because Facebook decides based on what the breast looks like, not who it actually belongs to. And so we’ve seen examples where trans men and trans women have had photos taken down. We’ve even seen examples where prosthetic nipples that looked real enough got a photo taken down.

Now this is a really fantastic campaign. It was for Pink Ribbon Germany, and it was called Check It Before It’s Removed, which just in case anyone didn’t catch that, they’re talking about both checking your breasts for a lumps and for possible cancer, but also before it’s removed from social media.

So, they put this up there intentionally, designed these photos that fit perfectly on your Facebook wall or Twitter, and encouraged people to actually break the rules. And what happened was that I posted this very image to Facebook, and because it was my “second offense,” I was banned for twenty-four hours from the site.

Now, let me tell you what that’s like, because we’ve spoken to the media quite a bit the last couple days, and I made the mistake of reading the comments. And one of the things that I found was that I don’t understand Facebook. It’s not the Internet. It doesn’t really matter. You can go somewhere else.

But what I found when I was banned was not only that I couldn’t post to Facebook or send messages to my contacts, which might seem fairly insignificant. I also couldn’t administer pages that I run for my job. I couldn’t use Spotify, which I pay for. I couldn’t use Tinder. I couldn’t comment on the Huffington Post, which uses Facebook’s comments. And so an entire world was cut off for me, not just my Facebook network.

Now, for me it was only twenty-four hours, but I run a project called onlinecensorship.org (and if you’re ever censored, please come to us), and we collect reports from individuals who have experienced takedowns or account deactivations on social networks. And from those reports, we’ve learned that these bans can extend to thirty days, and that they can be issued repeatedly.

And so while support for terrorism might get your account taken down immediately, violating the rules against nudity seems to result in ban after ban after ban. And so people who regularly break this rule will find themselves cut off for thirty days at a time just over and over again, indefinitely. There’s no reset button.

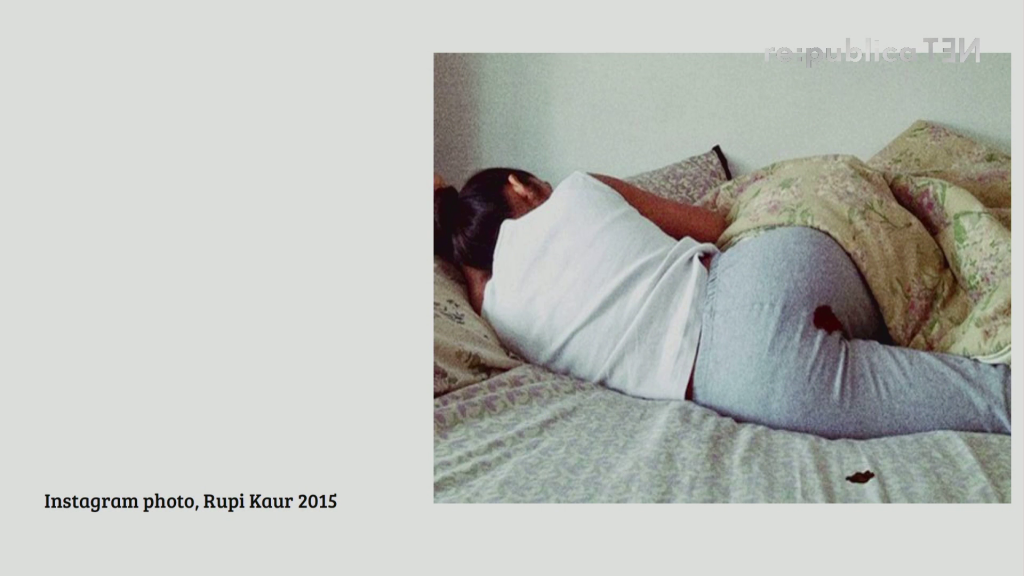

From “period.” series, by Rupi Kaur

Wageknecht: So, this is another example of an artist and a project that was actually removed from Instagram. Again, Instagram is owned by Facebook. So, she was looking at how you demystify a period. Fifty percent of the world experience this. We have dates and weddings and vacations that we work around these things, but it’s nothing that anyone really talks about. So again, it’s a fully clothed woman. But because of something in the image, the entire image was removed as well as her account.

York: And Instagram is owned by Facebook, and one of the other things that I’ve seen through my work and over the years is that different bodies are treated in different ways. Many people post their bikini shots on Instagram, but some of the content that I’ve seen taken down has been larger women wearing bikinis. So, they’ll have their photos taken down, but skinny women will not. There’s quite a bias there.

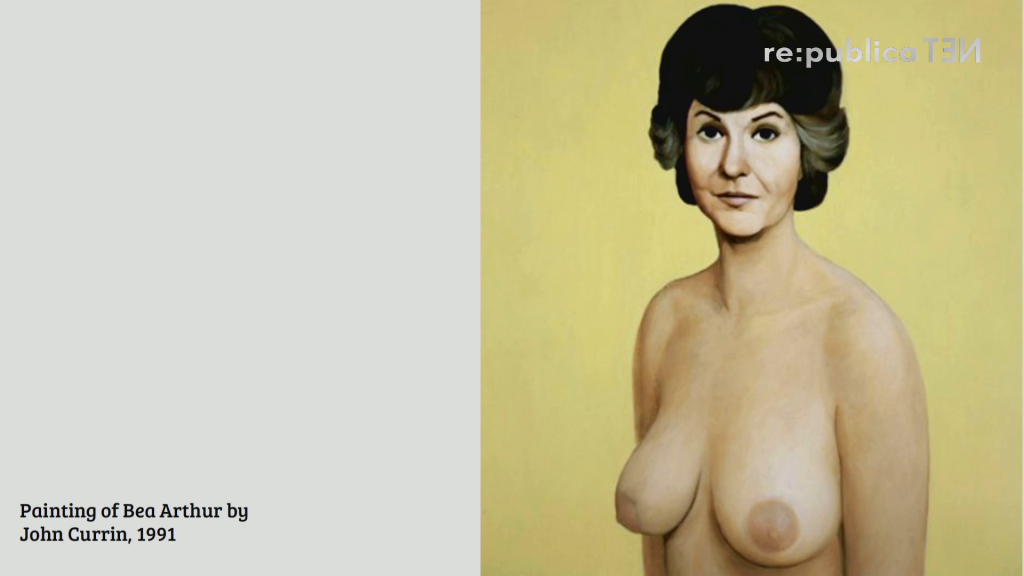

Now, Facebook also says that they allow photographs of paintings, sculptures, and other art that depicts nude figures. As we saw, the Venus de Milo…perfectly fine…high art…classic…everyone knows what it is. But what happens when you post lesser-known art?

Anyone recognize this person? I’m guessing if you’re American or maybe over thirty? So, this is Bea Arthur. She starred in a TV show called The Golden Girls. She also had a wonderful career before that, but this is about that era. This is a nude painting from 1991 called “Nude Bea Arthur” by John Currin. And this was my first offense. So, last fall at Netzpolitik Konference, I give a talk just after this had happened. I posted this image, and I asked my friends to please report on me. Because the way that Facebook works is that it encourages you to snitch on your friends. So, I asked my friends to do this, they reported it, and the result was that the photo was taken down. I wasn’t banned for any period of time, but the photo was gone and I couldn’t repost it. I was able to successfully appeal that decision, but it still counted against me as an offense.

Wageknecht: So, Facebook has approximately 1.4 billion users. And when you think about this in the context of countries or states, they typically also have more power and social capital than any country or king or state or anything in the world.

https://vimeo.com/60994603

So, this is a project I did in 2012, 2013, in collaboration with someone named Pablo Garcia, who is an artist and professor out of the School of Art in Chicago. How many do you have been to porn sites?

Nice.

York: Oh, nobody wants to raise their hand.

Wageknecht: Thank you. Come on. There’s more, there’s more.

York: We’ve all done it.

Wageknecht: So, with this project we were really interesting in exploring kind of this taboo place of the Internet, where a lot of people don’t admit they go to, but the majority of us do frequent quite often. We spent about two months on a site called Cam4. It’s a site where it’s not just read-only porn, as I like to call it, but it’s read/write porn. So, you can actually interact with people through chat windows.

So, we started to ask them to pose. And we would give them images of really iconic, well-known pieces of art, and asked him if they could emulate that and recreate it for us for a small amount of money. We were trying to kind of go around these questions about what is porn versus art, and what is beauty versus manufactured beauty or real beauty. And how do these things kind of juxtapose when you see what is considered over the masses as art versus porn.

So, this piece was also shown in 2013 in New York during a thing called Internet Week. You’d think New York is a very liberal part of the US, and the piece was put up, and within a few days Google was next to us and decided to have it taken down.

So, it comes down to this question of it’s 2013, it’s the future. Like, we’re supposed to have jetpacks, all this cool stuff should be happening. But we’re still debating this core moral question of like, what is art? What is porn? Is there a difference? And how you delineate those things?

So, I guess it really came down to the question of who makes the decisions and how can you [refute?] when you can’t? Because when Google pulled down the work in the exhibition, I tried to fight it. I argued it, and there was ultimately no one I could speak to. And that was being physically present. So it was really a wake up call about how the online transitions to the real.

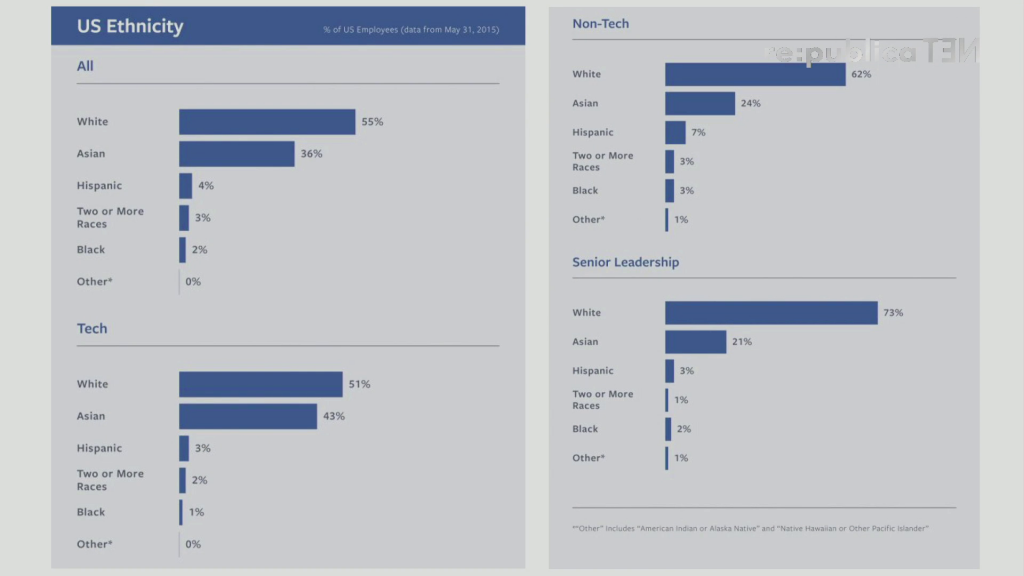

York: So, to that question, “Who does decide?” I think it’s worth looking at the statistics of these companies to see who’s working there and who’s making these decisions. Now, some of you may have seen Sarah Roberts’ talk yesterday, and she talked about content moderation and who the people are actually making the judgment. And I think that that’s a big part of it, but so is whoever makes the decision at the top.

This is the US staff of Facebook, and the breakdown of ethnicity. Fifty-five percent are white, 36% are Asian, and everyone else is under 4%. In terms of men and women, we don’t have that slide here, but it’s over 70% men in leadership positions. And that’s on both policy and technology, as far as we can tell.

So, what that says to me… Now, I don’t think necessarily that these are prudes, that these are people who believe that nudity is wrong. But this is so ingrained in American culture. We have it in the way that our films are regulated, the way that our television is regulated. And the problem here is that Facebook, as an American company, is making these decisions for the entire world.

We restrict the display of nudity because some audiences within our global community may be sensitive to this type of content — particularly because of their cultural background or age.

Facebook Community Standards [presentation slide]

But this is interesting. Because what they say about that is that they restrict the display of nudity because “some audiences within our global community may be sensitive to this type of content particularly because of their cultural background or age.”

Now, if I can read between the lines here, what I think they’re saying is “We don’t want the government of Saudi Arabia to block us.” It’s a real threat, and I think economically what these companies see is we have to create this flat, dull global standard for speech that allows everyone to be happy. But what does that say when we’re teaching our children that nudity is wrong? That women can’t be topless but men can.

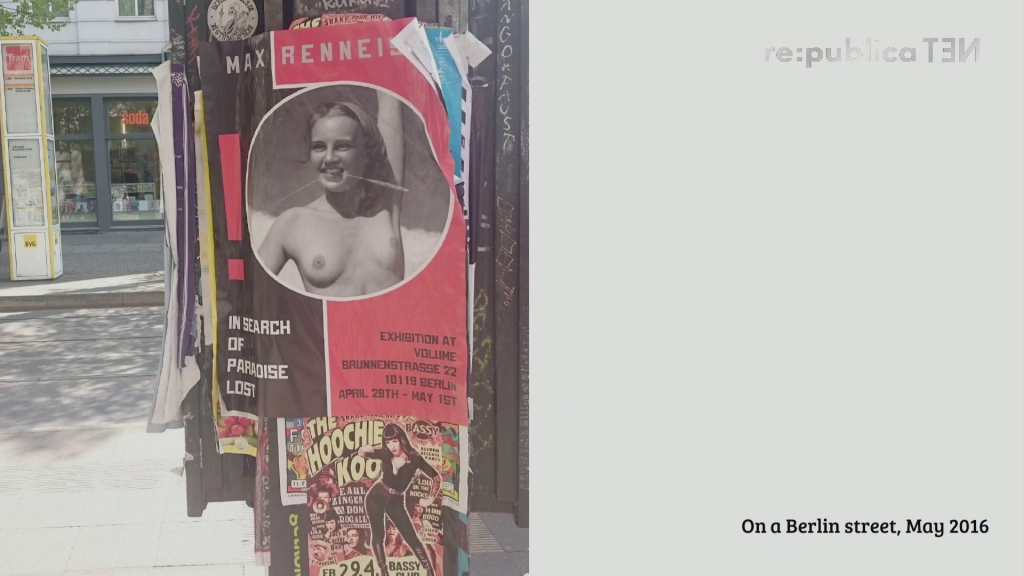

I just want to leave you with this slide here. This is a picture of from Berlin about three days ago, near Rosenthaler Platz. If you’ve walked around recently, you’ve probably seen this poster. It’s for a local art exhibition. And I was sitting at a cafe and I noticed the poster, and I decided to watch. And you know what I didn’t see, is I didn’t see a single parent cover their child’s eyes. Because it’s fine. It’s acceptable. So, why is it okay on a street in Berlin but not on Facebook, a global platform that we all use? Why do we want to teach people this double standard of women’s bodies? Why do we want to treat bodies like pornography. And I would even go a step further with what we’ve been talking about, and say why is pornography even wrong?

Wageknecht: So, as an artist it’s also I think really important—again like what really was bringing up, as artists and cultural capital creators you sort of think about the implications of this. And do you make nudes? Do you put them online? Do you expose them to a community of 1.4 billion, and what are the implications of that being deleted to your personal practice, to your social circles, and everything?

York: And of course we recognize that there are concerns around security, as well. We know that there’s a talk tomorrow that we recommend, Joana Varon, who was the other speaker, sorry?

Wageknecht: Joana Varon and Coding Rights.

York: Yes. You should definitely see their talks, and save nudes. But if you’d like to talk to us a little bit more, you are welcome to. And we like to open up the floor for questions, if that’s alright with you.

Mushon Zer-Aviv: Thank you, that was really interesting. What would you recommend as an alternative guidelines, or should there be guidelines at all? Addie, I know you’re a parent. And me as a parent, I wouldn’t want the Internet to be the one that moderates, for better or worse, the whole concept of nudity and sexuality to my children. So, do you have an idea of an alternative guidelines, or or is that more of a provocation?

Addie Wageknecht: For me, my son’s six, and it’s starting to become a question because he is becoming fluent in language enough to start navigating the Web on his own. But ultimately, I don’t see necessarily a difference between the online and the real. So, it’s a question of, do his friends online show it to him or does he discover it with his friends socially in real? Because when I was younger, we would find the porn in the in our friends’ parents’ drawer, and that was like, how you discovered sex. So, I don’t really necessarily see a huge difference between the two.

Jillian York: So, from my perspective I think that there are a couple things that Facebook could realistically do to make this a little bit better. I think the first one is treat women’s and men’s bodies the same. It’s fine if they decide, for example, that they don’t want to show anything below the waist. If they do that, fine. Treat men and women’s bodies the same. But right now they’re not doing that, and they’re they’re essentially perpetuating the sexism and teaching it to the next generation.

The other thing that I would say is that companies like YouTube, rather than completely banning nudity, they put an interstitial that says you must be eighteen to click through, and you have to have a YouTube account. Presumably for a parent that would be enough of a barrier to make sure, for example, that your child has the right account, that they have the settings clicked in. They could also have child’s settings that parents can set up. I would be fine with all of those things. I don’t find that to be censorship. But I think that blanket banning it is what’s really problematic to me.

Audience 2: Hi. I was wondering whether you thought it would be a good idea to have a nationally-based algorithm tried to implement local norms so that you don’t have one global standard.

York: So, I’m so I’m sort of torn on this, because I am sensitive to the fact that there are some places where no one wants to see— Well, I actually don’t believe that. I think everyone wants to see this. But I believe that there are some places where it’s treated differently. At the same time, I believe in one Internet. I believe in a global Internet that is for everyone. And I know that not everyone will agree with that, and that’s fine. But I think that it would be really… Once you institute algorithm like that, who’s to say, “Okay, now we’re going to ban images of women entirely in this country.” That would not be acceptable to me. And so treating cultures differently in that sense rather than giving people the autonomy and responsibility for themselves and their children and families, I would be skeptical.

Further Reference

This presentation at the re:publica site.

“Who defines pornography? These days, it’s Facebook.” by Jillian at Washington Post.