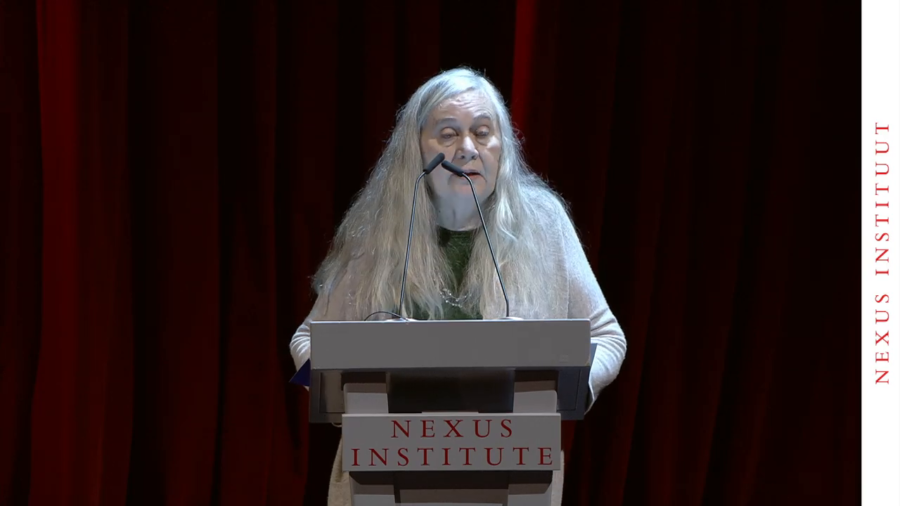

Marilynne Robinson: It’s wonderful to be here in this beautiful city. It’s wonderful to take part again in one of the great intellectual centers of contemporary life, The Nexus Institute. Such a pleasure to be here among people whom it is an enormous pleasure and honor to know.

So. I will not solve the questions that Rob has broached, but here’s what I have to say about them.

Modern Western societies are not organisms that thrive or perish as one thing, one mind, one experience. They are compacts, based on the expectation that those charged with responsibilities will carry them out in good faith, and crucially that those who are relatively powerful will not seriously abuse, exploit, or simply neglect those who are relatively vulnerable.

Democracy is profound mutual courtesy, an ethos of mutual respect, and is in this sense deeply spiritual. It should never be forgotten that Jefferson asserts human equality in the terms of the Biblical creation narrative. The dignity conferred on each individual by his creator is to be acknowledged as inalienable, worthy of all respect. Failure in this regard has always afflicted American democracy, and every other democracy of which I have any knowledge. This spiritual failure has now become conspicuous, consequential, shameless—and in America, organized under the auspices of the Republican Party.

It startles me that I feel justified in saying such a thing. It appalls me that it is in urgent need of being said. But the importance of this deviation from the first given of the American democratic order, this apostasy so to speak by a wealthy establishment presence, is truly threatening.

To trust one another with our ballots, and then to accept the decisions reflected in them, has always depended on an ethic of mutual respect which for the moment is not to be assumed. It is hard to imagine what will restore the integrity of the system, other than a spiritual awakening. Which could happen, since old white people like me are trudging toward the exits, demographically speaking, bearing away a great part of the fearfulness and sanctimoniousness that has burdened our politics. There are vast cohorts of young people and newly-aroused and enfranchised minorities for whom the founding documents are authoritative and beautiful. We can begin our recovery by respecting them. An easy first step because they are eminently deserving of respect.

Decline emerges as an idea very often, perhaps continuously, though it finds greater or lesser degrees of response from one iteration to the next. Those who raise the alarm in the intervals when there is little consensus to support this view of things are later seen as prophets. They add to the chorus or to the literature to be deployed when such consensus does begin to emerge. If, historically, a growing sense of decline precedes catastrophe, perhaps this is true because the idea predisposes the culture to nihilism, and also to the desperate battle against nihilism, which is the other side of the same coin. These two apparently contrary movements act as accelerants to excitements that arise between them. Because they both proceeded from categorical and very negative assumptions about people in general—“the masses,” as they are often called in this context. This low estimation means that no vision is offered of a future, an ongoing life, for the culture that people in general could wish to have a part in.

I could be describing the collapse of a democracy, or I could be describing the means by which a democracy can survive and overcome the great vulnerabilities by which democracy is always threatened. It may not be very long before the matter is determined one way or the other.

Our government has been based in a greater degree than any of us were aware on norms and customs, unenforceable deference to precedent, and restraint in the face of opposition. Our incumbent is intent on remaking the office to suit his own character, and is both limited and protected by a tradition of respect for the office of President. Respect which he seems not to share.

When norms are violated with impunity will they function as norms again thereafter? Will the standards of conduct they have supported be changed by the attempts that are likely to come to enforce them by legislation, assuming a restoration of something like normalcy? In other words, will a complex institutional stability be compromised, changed, or lost, leaving us with in America we cannot foresee and will not have chosen?

Many essential things are in a state of true indeterminacy, so it seems. Se are on our way to learning how our politics live in our civilization, how we understand our problems and what resources we bring to mitigating them. If we subscribe to decline as an interpretation of our problems, our democracy will indeed fail.

The concept “decline” by implication takes a former state of things to be good, and evil to be those tendencies perceived at least as departing from it. Evil is a word I’m generally reluctant to use. But in the context of cultural pessimism it evokes precisely the nature of what is to be feared and resisted in the dissolution these people think they see. To call anything evil is to lift it out of the ordinary, the secular, to assume in it a special energy that places it beyond the strategies of reason and good intent, and that demands hyperalertness and recourse to very extraordinary defenses. This idea of evil is holiness inverted, Satan loose in a godless world. Speak of this devil and he is very likely to appear.

I do not believe, I cannot imagine that any human being could be without a spirit, a soul. I believe as a matter of faith as well as observation that spirituality arises out of the individual spirit, solely by the grace of God, through difficulty, despite neglect, in the absence of help and approval, in tactful or tentative silence and secrecy as surely as in the recitation of any creed. I believe that human beings have an endlessly demonstrated tendency to refuse to acknowledge the spirit in themselves and crucially, in culturally selected others: slaves, aliens, women, Jews, heretics, enemies real or perceived. The blindness they induce in themselves releases them from the felt constraints of justice, mercy, and reverence, and monsters them individually and as societies. This is a brief history of humanity’s crimes against itself.

American Puritans, ancestors of my tradition, the people who gave us Thanksgiving, did not celebrate Christmas, which they considered a pagan festival. But they did in a larger sense celebrate the Incarnation, the faith that God himself could pass unnoticed in this world, an ordinary man according to Calvin one physically marred by poverty and labor. Who might he not be? He told us who he was, the hungry, the sick, the imprisoned, the stranger. I believe there was once a convention in a liberal state that there is courtesy owed to those with whom he explicitly identified. Well, society giveth and society taketh away. But for Christians, the Incarnation changed the world in one great particular. We know what we do. Whom we slight, insult, ignore, forget. The parable that is our faith would tell us that the spirit is always real, always present, waiting to be seen. Thank you.