Jonathan Lovvorn: Welcome everyone to the panel. I’m very excited to be moderating on this particular issue. Thank you to the Berkman Klein Center, the Harvard Student Animal Legal Defense Fund, the Harvard Animal Law & Policy Program for making this possible. It’s great to see such a big turnout on this issue at the intersection of animal law and technology innovation.

When we talk about animal law, of times we start by talking about the dualistic nature of the common law, and the fact that the law divides everything under the sun into persons and things, and the latter category including property. We do this so much that most laws and regulations don’t even bother to stop and talk about who they apply to. So we have statutes, constitutional provisions, that confer benefits and rights but totally omit any discussion of who’s included.

This problem is being challenged on two fronts. So, that duality doesn’t fit so well with two different lines of development. The first is the scientific knowledge and expansion every day about animal sentience, animal intelligence, animal agency, animal creativity that takes animals to a place that doesn’t fit very well within this dualistic framework of persons and things.

The second place is the advancement of computer technology and artificial intelligence, which also tests the boundary of this traditional divide between persons and things.

So the case we’re going to talk about today is going to be a jumping-off point for that larger discussion about how we deal with the other, and how we deal with things that have attributes of persons and are held outside the class of persons. And we’re going to use the monkey selfie case as a jumping-off point. And I’m going to introduce our panelists really quick, and then we’ll do an overview of the case, and then have a cross discussion and then open it up to all of your questions, and I’m sure that you have a lot.

Our first panelist on my left is Jeff Kerr, who’s been general counsel to People for Ethical Treatment of Animals and the PETA Foundation for twenty-five years. Jeff is one of the most knowledgeable and well-known experts in animal law in the entire world. We’re extremely fortunate to have him here. He built and now leads the largest animal rights-focused legal shop in the United States. His cases like the monkey selfie case have advanced scholarship and popular discussion about animal rights considerably. His legal team was also just awarded Best Legal Shop in 2017 by Corporate Counsel Magazine. So I’m personally very happy to have Jeff here because I’ve known him for many years and it’s great to get a chance to catch up.

We also have Kendra Albert, who’s a Clinical Fellow at the Cyberlaw Clinic and the Berkman Klein Center for Internet & Society. Kendra’s a 2016 Harvard Law School graduate. Her work on Internet and copyright issues has been published in Green Bag, the Harvard Law Review, and Wired. Before law school, Kendra worked as a research associate at the Berkman Klein Center for Internet & Society and also worked at Public Citizen, Electronic [Frontier] Foundation, and Cloudflare. Welcome to the panel.

On my right we have professor Christopher Bavitz, Managing Director of Harvard Law School Cyberlaw Clinic, which is based in the Berkman Klein Center. He also co-teaches the Counseling and Legal Strategy in the Digital Age seminar as well as the Music & Digital Media seminar. His practice focuses on intellectual property, media law, entertainment, music, technology. Prior to joining the Clinic, Chris served as Senior Director of Legal Affairs for EMI Music North America.

Finally we have Tiffany Li, who’s an attorney and Resident Fellow at Yale Law School’s Information Society Project. She leads the Wikimedia/Yale Law School Initiative on Intermediaries and Information. She’s an expert on privacy, intellectual property, and law and policy at the forefront of new technology innovations. She’s also an Affiliate Scholar at the Princeton Center for Information Technology and has been honored with Transatlantic Digital Debates fellowship, a fellowship on information policy from the International Association of Privacy Professionals, and is a Fellow and Founding Member of the Internet Law and Policy Foundry.

So welcome all of you. I think at this point we’ll turn it over to Jeff to give us an overview of the case. And then we’ll have some discussion.

Jeff Kerr: Good afternoon everyone. John, thank you very much for the introduction. It is just a thrill to be here, and this wonderful turnout, we’re all very grateful for your time. As Jon mentioned, I am going to give a brief introduction. I do want to thank Kate Barnekow and the SALDF for inviting me here. And I hope you all enjoy this very much.

I had to chuckle a little bit while I was waiting for today’s presentation. I saw this publication, Our Bicentennial Crisis—I think you’ve all probably seen it. I was struck by…in it the author was talking about how prescient Harvard was in the late 1990s by creating the Berkman Center, notwithstanding the fact that at least one judge had argued that “the concept of ‘cyberlaw’ would be as useful as the concept of ‘horse law.’ ” So, the irony is not lost on me. We’re here to talk about cyberlaw and also monkey law in this case, but close enough.

I want to talk to you just briefly to give you an overview to frame the case, to frame the monkey selfie case, so that we have a context. And we start with the question of what is copyrightable? This is a selfie photograph of one of my colleagues in the legal department. Clearly a copyrightable photograph, and in case you had any question about that, that’s the certificate of copyright registration for that photograph.

Now, we go to the Copyright Act, and copyright applies to “original works of authorship fixed in a tangible medium of expression, now or later developed.” That’s the basic definition that we’re dealing with.

And “original” means “little more than a prohibition of actual copying.” So it’s a very, very, very low bar.

And “as a general rule, the author” (that’s the legal term used for who creates a copyrightable work), “the author is the party who actually creates [it].” And therefore copyright ownership “vests initially in the author or authors of the work.”

And then correspondingly, “the legal or beneficial owner of the exclusive right under the copyright is entitled” to sue to protect it.

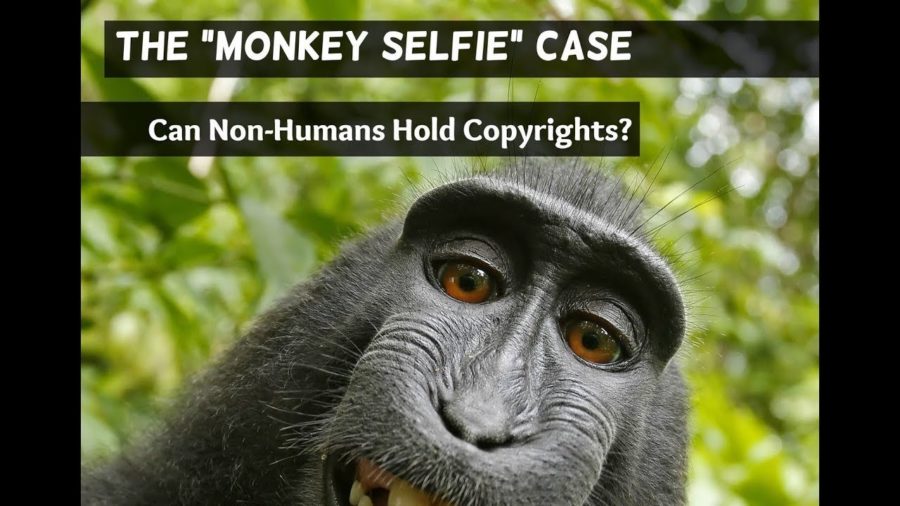

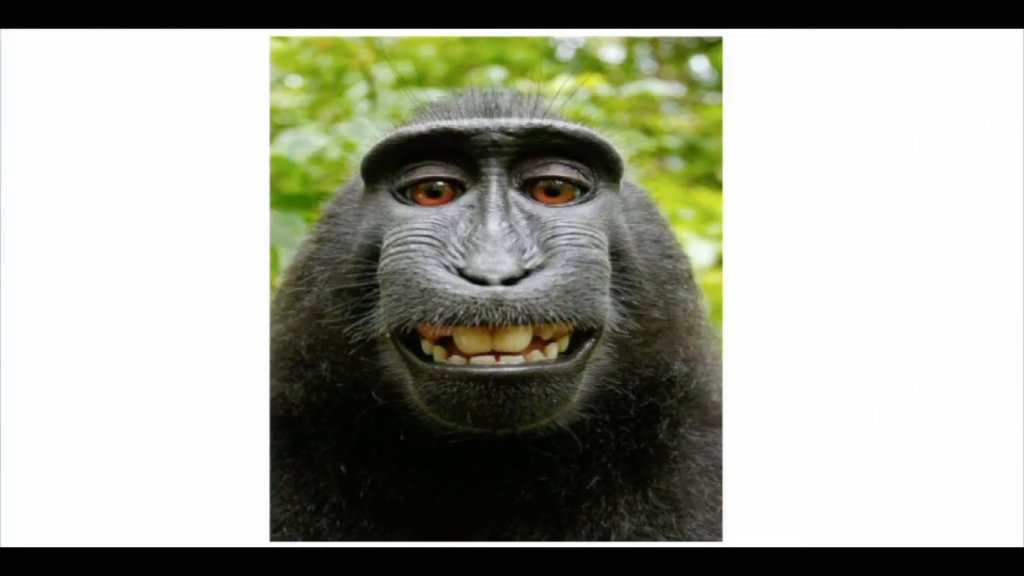

This is the star of our show. This is the famous monkey selfie photograph. And this is Naruto. He is now a 9 year-old crested macaque who lives on the island of Sulawesi in Indonesia. They’re called crested macaques— You can’t see it as well in his selfie, but it’s because of the Mohawk-like crest of hair on the top of their heads.

And let me tell you a little bit about Naruto and the macaques. They are critically endangered and their total population is now estimated to be between four and six thousand. And their numbers have decreased approximately 90% over the last twenty-five years due to population encroachment, and being hunted for bush meat.

They are highly intelligent and capable of advanced reasoning. Like us, they’re vision-dominant. They have stereoscopic vision. They see in color. And so anything that has their image in it or the projection image or is a visual stimulus to them is incredibly interesting. They also have grasping hands just like you and I do. They have opposable thumbs. They have fingernails. And they are able to do incredibly dexterous actions with their hands, including one of their most important social grooming traits is to pick very small insects off of one another.

Now, Naruto and his other macaques eat by foraging. And so they are regularly encountering humans, whether in the nearby village that’s next to the preserve where they live, or to people coming into the preserve. It’s heavily touristed area. So they regularly encounter photographers, whether tourist photographers or professional photographers, Naruto and his fellow macaques have grown up around and very used to video cameras, big television-type cameras, all the way down to our cell phones. And they’re used to being around them and being used without endangering themselves or harming them.

Now, let’s rewind to 2011 when a photographer named David Slater was in Indonesia and he was following the macaques for several days. And he stopped to rest and put down his cameras. And Naruto, then 3 years old, came up and picked up one of his cameras and started looking at it. And he made the connection… By Mr. Slater’s own admission he made the connection between pushing the shutter release button and the change to his reflection in the lens when the aperture opened and closed.

“[M]acaque smiles at itself whilst pressing the shutter button on a camera.”

“[M]acaque pulls one of several funny faces during its own photo shoot, seemingly aware of its own reflection … suggesting to me some form of fun and artistic experiment with its own appearance.”

“Posing to take its own photograph, unworried by its own reflection, smiling. Surely a sign of self-awareness?”

[presentation slide]

And so the quotes I have here, these are Mr. Slater’s quotes from the book of photographs he published that contain the monkey selfies. So these are Mr. Slater’s own words about the self-awareness, the sophistication, and the intentionality and purposefulness of what Naruto was doing in taking the photographs.

“… not just highly intelligent but … also aware of themselves … It was just a matter of time before one pressed the shutter resulting in a photo of [him]self. [H]e stared at [him]self with a new found appreciation and made funny faces – in silence – just a we do when looking in a mirror.”

[presentation slide]

And again. I think it’s just so important to understand this. This and the other photographs that Naruto took were entirely and exclusively intentional, purposeful acts. And it was kind of funny—as an aside, some of the photographs were of the sky, they were out of focus, partially he was in the frame. Sounds a lot like probably all of our vacation photographs as well. So the similarities continue.

“[H]e also, importantly, made relaxed eye contact with [him]self, even smiling … [H]e was certainly excited at [his] own appearance and seemed to know it was [him]self.”

[presentation slide]

Just some more information about how he reacted to the photographs. I’m trying to go through this quickly for time.

“These photographs are not the result of an accident; they result from specific and intentional manipulation of the camera by Naruto.”

Brief of Agustin Fuentes, PhD, amicus curiae [presentation slide]

And when we argued the case to the Ninth Circuit (I’m fast-forwarding a little bit; I’ll come back.), supportive of the notion of what I just said was Agustin Fuentes, a PhD at the university of Notre Dame, who is an expert in macaques, who said, “These photographs are not the result of an accident; they result from the specific and intentional manipulation of the camera by Naruto.”

Now, the copyright law does not— When we found out about these photographs, it was as a result of a dispute between Mr. Slater and Wikimedia. Mr. Slater published the photographs and they became internationally famous. And then Wikimedia posted the photographs, especially the famous monkey selfie, on their public domain or free to use web site. And Mr. Slater took exception to that, claiming that was a violation of what he claimed to be his copyright.

Wikimedia responded—they had two responses. The first is, “You’re not the copyright owner because you didn’t take the photographs, the monkey did.” And, “because the monkey took the photographs, and monkeys can’t own copyrights, they’re in the public domain.”

Well, we saw the story and we agreed with the first part of what Wikimedia said, but we disagreed with the second part. And so we brought—PETA—brought as next friend of Naruto (in other words as the representative of Naruto), we brought a copyright infringement lawsuit in federal court in the Northern District of California San Francisco, against Mr. Slater and the publishing who published the book that had as the cover the famous monkey selfie photograph, claiming that they were infringing on Naturo’s copyright.

What we argued very simply was that because the copyright law does not expressly require human authorship, it simply vests the copyright in the author or the creator of the work, Naruto was the creator, therefore he should be entitled to own the copyright.

And this was consistent in our view with what has been a continual expansion of the applicability of copyright law throughout our country’s history.

Now, one of the other things that we argued was that there is no requirement that an author derive any monetary gain from his work nor that he intend to publish it. That question, you could understand how that would come up. I got the question earlier today while people were still coming in, “Well, how could he do anything with it? How could he, Naruto, do anything with it?” And the answer’s the same as it is for a minor child, or for a mentally-incapacitated human. And that is that you do it through representatives. And that’s what we were asking the court to do in the case basically, was allow us to be Naruto’s representative. And once the copyright was granted to him, that we would, completely free of charge, not taking a dime, administer the copyright in the photograph, to license the photographs, etc. so that every penny raised could benefit Naruto and his other macaques and protect them and their habitat in Sulawesi.

So at the district court level, the judge granted the motion to dismiss the laws finding that animals could not own copyright under the Copyright Act. And of course that was the crux of the issue. And so we appealed to the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals and we argued the case toward the end of last summer. And after the case had been argued and before an opinion was issued, we entered into a settlement with Mr. Slater by which he agreed to donate 25% of his gross proceeds from licensing the photograph, forever, for the benefit of the macaques in Indonesia.

So, that’s an overview. I think we can probably go on with the panel discussion.

Jonathan Lovvorn: Thank you so much for that, Jeff. Obviously there’s a whole lot to unpack there. I think where I’d like to start is maybe to turn to our other panelists and get some initial reactions.

Christopher Bavitz: Yeah, sure. Thank you. This is great. And I really want to thank Gabriel in particular for getting this all going and starting this conversation. Just a little bit of context before we get into the substance is, some of us were talking earlier about the fact that the Berkman Klein Center, where Kendra and I and many other here are based is sort of in the midst of this very large research initiative in collaboration with friends over at the MIT Media Lab looking at artificial intelligence and machine learning and algorithms, and thinking about legal and regulatory models that relate to that. And when Gabriel first reached out and said could we get some copyright folks to come on a panel and talk about that, we’re happy to do that because we like to geek out about copyright law and this has been an interesting case to follow.

But one of the reasons why I think Berkman institutionally said let’s put this into our weekly series is that with surprising regularity, this case comes up when we’re talking about artificial intelligence and when we’re talking about the increasing capacity of machines, of computer programs, of software, to generate works that I think all of us would describe as sort of creative or expressive works by any definition. So I think it’s become if nothing else a really useful sort of framing device in a world that doesn’t really have a lot of great, useful framing devices yet for some of these very bleeding edge technologies as we think about exactly what it means to be a creator and whether you know, the intermediary piece of software that you use to generate a creative work is itself a creator or if it’s merely a tool akin to whether it’s a paintbrush or a synthesizer or a camera. Anyway, this case kind of tees up a lot of those issues.

On some of the substantive issues I think we’ll all have reactions. I’ll just throw out a couple to kind of get us going. I think that one of the things that concerns me about the way this case was postured, and I think it came up in the initial comments, is that it kind of came down to a dispute over whether this one person or this one monkey owned the photograph. And there is a very viable third way here, which is that nobody owns this photograph. And I think that there’s a lot from a policy perspective to say in favor of that outcome here, simply in the vein of trying to insure that we have a robust commons of works that we can all use and rely on in our own creative endeavors.

So I think that there’s a lot to critique here about the photographer’s position in this case that he owned this photograph that was snapped by the monkey. But I don’t think that that necessarily means that we have to therefore run around and find another owner for this photograph, right. There could be a perfectly reasonable outcome here that no one owns it. There are lots of things that no one owns, and that’s a good thing—data and information and facts and ideas, and the list goes on. There are provisions in the Copyright Act about that. So, I just wanted to kind of make sure that’s out on the table.

The other thing I’ll just mention briefly and then maybe we can we can dig in a little more is…as I’ve thought a lot about this case is… Kind of before we get to the specific provisions of the Copyright Act that were put up on the screen, we step back and say why do we have copyright protection? What’s the purpose of this? And lots of people disagree about this, there’s lots of different theories. But the main one, the prevailing one I think it’s fair to say in the US at least, is that copyright creates an incentive. Our Constitution says that Congress, among the very limited list of things that Congress is allowed to do like you know—really along the lines of wage war and print money—kind of amazingly is pass intellectual property laws that incentivize people to create stuff. And that incentive exists, arguably, because if I sit down at my desk to write my great American novel or to write my symphony—I’m going to sit down and engage in a creative act—I’m incentivized to do that because at the end of that creative process I know for some limited period of time I will have copyright protection in it. I will then be able to exploit it. I can kinda do whatever I want with it.

That’s a fiction, right. So let’s— You can poke holes in about sort of the incentive theory, but let’s stick with it for a minute because that’s I think the prevailing one here. I’ve struggled a lot to figure out how to map that onto a world where either computer programs, or for that case Naruto, are incentivized by bestowing on them copyrights, to do the kinds of things that they do.

Now again, the selfie that was put up on the screen of the person…when I go and take a selfie of me, or me and Kendra, or me and my kids, I’m not doing that because I’m incentivized to do it by virtue of thinking long ahead, “Wow, this will give me my whole entire lifetime plus X number of years of copyright in the selfie.” So again, we have to recognize that’s a bit of a fiction. But I think even that kind of fragile fiction to me falls apart even further I think we’re talking about animals and really a whole range of nonhuman potential creators and copyright owners.

Lovvorn: That’s very interesting. Kendra or Tiffany, you want to—?

Kendra Albert: Yeah. So I’ll jump in next. So in addition to some of the things Chris raised, I think when I’m thinking about the Naruto case, one of the key set of concerns that I have personally I will relate to sort of two broad categories thinking about administrability and thinking about speech. So you know, it’s true as Chris said that in the Constitution, Congress is given the right to promote the progress of science and Congress is supposed to promote the progress of science and the useful arts. And you know, we have 200, 300 years of debate about how best to do that and whether the copyright system accomplishes that goal as currently constituted.

But one other thing to think about in the sort of realm of when we’re talking about copyright specifically is it’s a form of speech regulation in addition to an incentive structure, right. It’s both about creating a symphony, but it’s also about saying, “Hey, you can’t perform my symphony without my permission.” And I think that especially when we look at the context of nonhuman actors, you know, for me that raises real questions about how we might give people who we may not initially think of as the ones who we want to have power over that kind of speech, power over that kind of speech through intellectual property protection.

And I know PETA’s been really active in the fight against ag-gag laws, which… Agricultural gag? I’ve never heard it referred to in the long form that’s not shortened. But laws that prohibit sort of people going in and filming abuse that’s happening in factory farms. And I think one of the things that we might want to also think about in the context of when we grant additional IP protection is what types of harm might we see that result from from the speech being owned in ways that it wasn’t previously. For example, speech in the public domain, or works in the public domain, don’t necessarily come into those same kinds of speech restrictions.

The other concern which I think is more about just sort of the practicality of these things is we already see in our current copyright system plenty of examples of how even people with very very tenuous claims to copyright use intellectual property protection against speech they don’t like. And that this comes up in contexts like DMCA takedowns. It can come up in video games. It can come up nonconsensual pornography. It comes up in a variety of different places. And so once you have an entire class of folks who might be able to produce works but who there isn’t sort of a natural…one representative for who sort of automatically advocates for them. So animals or even like, AI, you get into a whole debate about who owns it and who has the right to control it that you know…we are already having in small scale in our current copyright system, and the sort of potential for the even larger administrability problems of nonhuman actors really concerns me as someone who already sees real speech problems in the way that copyright is administrated online.

Lovvorn: Tiffany?

Li: Sure. So just as a brief caveat, I am working for the Wikimedia and Yale Law School Initiative on Intermediaries, but my opinions obviously do not necessarily represent those of the Wikimedia Foundation.

That being said, I want to talk a little bit about AI and the concept of nonhuman authors generally, including animals.

So, I think that one thing we have to recognize is that currently under the law, copyright is only available for human authors. And the most recent guidance we’ve seen from the Copyright Office has specifically used the word human. Whether this is a positive or negative can be debated, but that’s what we have under the law and under our administrative guidance right now. What this means is that actors like Naruto or actors like IBM Watson, for example, can’t be considered authors under current law.

So the more interesting question, though, is should they be considered authors? Or should we change our laws to accommodate for these new forms of authorship? And I think when we’re looking for artificial intelligence, we see a few different models that different scholars have created. There’s first the idea that I think Chris mentioned first about just letting loose these artworks or these works into the public domain, because you can’t really determine who was creating that work. And that of course comes with benefits to the public domain, but possibly negatives concerning incentives if you think that for example someone might be less incentivized to create the algorithm or the program if they know they can’t make money off it.

There’s also a model that claims that whoever designed the program or the artificial intelligence system should be able to own the copyrights because they should be able to get the fruits of their labor. This is very basic incentive theory again.

And I think what’s also interesting, which we haven’t really discussed yet, is the more UK or EU-based model of moral rights for authorship. And here I think there’s maybe a stronger argument for giving authorship to animals and AI. If we consider moral rights, we consider artworks (or just works) that are created as extensions of the author. We can then think of intentionality, creativity, what it means to be a creative artist, or to create a work. And in that analysis we may have, I think, more arguments in favor of giving copyright to Naruto or to an AI.

Under current US law, I don’t think we have this and I don’t think there’s a good foundation for this. US precedent on these issues has generally, again and again voted against giving copyright to nonhuman authors. This includes cases involving nonhumans like celestial spirits, a claimant said was writing or creating art through them. Obviously the spirit was not allowed to own copyright, and that was one precedent that we have to look at right now, considering AI and authors who are nonhuman moving forward.

And I think I’ll just end on one question, which is something that I think about a lot actually. Because I’m not completely sure that Naruto, or that animals, shouldn’t own copyright. I think right now they don’t under the law. But in the future, if we get to a point where we change our understanding of maybe just neuroscience or how animals think and react, and how artificial intelligence systems can think and react if they can be said to think and react… In that future scenario, then we might have to reconsider what is current law. I do think, though, right now we don’t have this in the law. But in the future we might.

Lovvorn: Interesting. Yeah. I mean, I’m going to go back to Jeff in a second, but what struck me was how…open the Copyright Act is with regard to providing no guidance on this particular issue. And then the Copyright Office’s policy was very interesting, because it didn’t cite any particular statutory structure, it just simply said natural acts, animals, and other creations of nature don’t qualify. Which I personally found very interesting, because last time I looked, I thought humans were both animals and part of nature. It sort of shows the duality of how they’re thinking about the separation of people from humans.

But it in terms of further development, Jeff what do you think about this? I mean the Copyright Act, and this is what I alluded to in opening, so many of our laws don’t specify who they’re talking about in granting rights or privileges. And so it seems like there’s enough room in the Act to allow this if the Copyright Office chose to do so.

Kerr: I couldn’t agree with that more. And that’s precisely what we argued. There is no question, just like with the photograph of my colleague that I put up, that if a human being had taken that photograph and somebody else tried to use it, everybody would line up 100% behind the human who took the photograph, claiming, “You can’t do that, that’s his or her photograph. They own the copyright.”

Our view from the animal rights perspective is well, it shouldn’t be any different simply because the photographer happens to be one of our fellow animals but simply not human. In our view that is the most basic form of prejudice, based upon species. And that’s exactly what we’re arguing about. And one of the arguments we had to deal with was this notion of well, the Copyright Act is silent on who can be an author. And I believe that’s just false, and I think the case law bears it out. The Copyright Act says it’s the author, and that cases have defined who the author is. And just like some of the other panelists have said, the Act is written intentionally broadly and open-ended. Because Congress said, “We can’t possibly conceive of all of the different types of technologies, advancements, or inventions that are going to come about.” And we’d be back here every other Tuesday giving a laundry list of new things that should be entitled to copyright protection.

Well, our argument was quite simply well, that argument should apply with equal application to the identity of the author. If you can identify an author— Now, no question, there may be circumstances in which the identity of the author who actually created the work may be a question. That wasn’t our case. Everybody, including the owner of the camera that was used admitted that Naruto himself, without any assistance, took the photographs. From an animal rights perspective, that should entitle him to the ownership of the copyright.

Now, that does get into a couple of other things that were raised, if I could take just a second. And I touched on it briefly in the introduction. It does require somebody other than Naruto to utilize, license, and monetize the work for the benefit of the author—Naruto and his other macaques and the habitat. But I do think it’s important understand that the Copyright Act applies equally, not for any kind of incentive but to protect the originality of the author’s work.

And I think it was Chris who touched on it, talking about your own personal selfies. Those are never intended— There’s no incentive to taking those. They’re never intended necessarily, except maybe on social media, to see the light of day. But nonetheless, even if you don’t want to use a copyrighted image, you have the right as the author and owner of that copyrighted image to prohibit the rest of the world from using it. And I think that that right of prohibition was overlooked in our case and is frequently overlooked in the discussion in relation to Naruto and other animals.

Kerr: Well, [crosstalk] I wanted to come back to that—

Albert: Can I just jump in briefly. So Mr. Kerr, with all due respect I think you’re overstating the clarity with which the Copyright Act doesn’t talk about who specifically might own authorship. Like, specifically in the definitions, when we talk about who might inherit copyrights it talks about children, and in the definition of children it talks about people.

So I think that at the very least, part of why I think I was trying to focus on what might we think about moving forward if we grant this, is that I do think there is both case law and the significant evidence in the statute that the Copyright Act is meant— Though that authorship designation is at its core referring to persons—some form of personhood.

And in addition, I also you know… Your categorical statements about prohibition are just like, legally incorrect. You know, we have Fair Use, which allows people to make use of other people’s works when it’s consistent with the statute’s factors. So I realize that your position on animal rights brings a set of strong statements to the table, but I think that the reality of how copyright is administered means that it’s in fact a bit more complicated than you’re presenting it as.

Kerr: Well let me—

Lovvorn: Well, before you jump in. Let me come back to— And I wanted to come back to Kendra, your point about the First Amendment. Because although I’m not an expert on it, it appears that the statute is at best ambiguous with regard to what they mean when they say “author.” And we have this across so many different areas of federal law that grant rights or duties and don’t really say who they’re talking to.

So what about the First Amendment aspect of this— And you know, when we have ambiguity in the statute, as you mentioned Kendra, copyright limits First Amendment rights, to what extent, Jeff, do you feel that that should play a role in deciding how we answer this particular question, both with regard to animals, or intelligent machines? Do we need to rather than follow the broad prescription of sort of expanding copyright, do we need to stop and pull back a little bit because copyright affects First Amendment rights?

Kerr: Well, I’m not a First Amendment expert, nor am I an AI expert. I’m the animal rights lawyer and I’m here to advocate for the animal’s perspective, as we were in the case. I think any time you get to what’s missing from the First Amendment—and let’s underscore the human First Amendment—the animals in our perspective are completely absent from that calculation. They have no real voice under the law. The laws are changing for the good because of the work that Jon and his colleagues, and I and my colleagues, and a lot of other really good people are doing around the world to try to advance animal law. But we still have a long way to go, and by and large the laws that exist are… I like to refer to them as animal exploitation laws, not animal rights laws. By and large they are more laws about the nature and extent to which human beings can abuse or exploit animals rather than it is about fundamental, enforceable legal protections. And when I say enforceable I mean enforceable in their own right in the names of the animals for themselves.

If I could touch on just a couple of other things. Kendra’s comment about Fair Use is very well-taken, and I wasn’t trying to eviscerate an entire category of copyright law by my statements. But to address the specific point about the use of the word “children” in who can inherent copyrights, yes that is in the Act. But it’s also very clear under the Copyright Act that corporations can own copyrights, and they don’t have children, either.

So I think our reading is entirely consistent with the notion that children are there for an inheritance perspective—I have no problem with that. But as with corporations, there’s still the ability for somebody other than a human being to own a copyright, who don’t have legally cognizable issue to whom it could be given.

Bavitz: There is a scholarly piece out there by Annemarie Bridy, who writes a lot in this area, kind of on that point about the notion of hu— Less about I think using Naruto as a framing piece for conversations about this technology, but taking the point that a corporation is an example of a nonhuman that can nonetheless be not just a copyright owner but actually an author in the context of works made for hire.

Lovvorn: And maybe Tiffany we could hear from you on— Do you have thoughts about this question and would those provisions referring to children and inheritors, would they also prohibit a copyright in your view from applying to artificial intelligence-created work?

Tiffany Li: Sure. So I think there are a few different things to talk about here. The Annemarie Bridy article is great. And I think that one thing she does mention when talking about corporations owning copyright is the fact that corporations at the end of the day are groups of people. So you consider it more of a collective copyright still owned by humans, not a true non-human author.

That being said, if we look at the legislative history or the history of the Copyright Act and how it’s been interpreted, I think that the point of the definition’s very interesting. But like I said before, I think under current law it’s difficult to find reasonable arguments in favor of giving copyright to animals. However, we have to look at the history of law. US law has not considered many people human beings. Actual human beings were not considered human beings. So in that case we have to think about the future. And if our current understanding is incorrect, if the day comes when we find that our current understanding of animal behavior and thinking and intelligence is incorrect, I think at that point we go back and look at how we’re interpreting the Copyright Act. But at this moment in time I still don’t see concrete reasons why under current law we could provide copyright for animals.

For artificial intelligence, it’s a little complicated again. Because you have less of an independent actor as you would find in an animal, and more of a programmed actor. Or an actor that has been… Well, you also have trained animals, so that’s a similar comparison. But you have works that are created, that have to be created at least with a human at some point in the system. With an artificial intelligence system, at some point there was a human involved.

With animal-created work, if you call it created work, it’s possible that there could be work created without the touch of a human being. So I think that’s a key difference, and that’s also a difference between the issues of animals, AI, and corporations corporations. Corporations again are all just a large group of people.

Lovvorn: Interesting. I think I’d like to take some questions from the floor before we run out of time.