If you are given the task to lecture on design somewhere in the Middle East, do you think you’ll need to tailor your approach? Maybe think about your references, the language, the vastly different background? The answer most probably is “yes.” But the reality of design education in the Middle East, and more specifically the Gulf Region, prove otherwise. Design education in the Gulf is constituted of imported curricula from the West, without actual appropriation to the place where design is taught.

Good afternoon. My name is Nawar Nouri Al-Kazemi, and I’m here to talk about design, and specifically design education in the Gulf region, also known as “al Khaleej.”

Since the late 1990s, design programs have appeared in more than twenty schools in the six Gulf states, Saudi Arabia, Oman, the United Arab Emirates, Kuwait, Qatar, and Bahrain. Though mostly in English language-based private universities, design programs are on the rise. Qatar alone, the second-smallest Gulf state, now has four design programs.

Curricula?

These design programs have different approaches and philosophies, but they all have one thing in common: their curricula are not tailored for this region. Graphic design, fashion design, visual communication, even in some cases architecture, are taught from a Western perspective with very little regard to the culture and history of the region.

While there are attempts at localizing design classes through objects that engage with local issues, such as designing bilingually or recreating contemporary designs of old objects as these images show, projects of such nature are limited to the instructor’s knowledge. That is not due to lack of qualifications of the instructors, but rather their lack of familiarity with the region’s culture and history. Since the majority of instructors are not from the region, it is hard for them to fully grasp let alone explore Khaleeji cultural heritage.

Khaleeji Cultural Heritage

To that end, I’d like to show some examples of the customs and traditions I’m referring to in the Gulf. These indicate a daily lifestyle, or some of the visual cultural references.

Image: Wikipedia, Varieties of Arabic

Most prominently, language. Arabic is the primary language used in the Gulf, but each Gulf state has more than one distinctive dialect, as this map shows.

Another attribute to the traditional lifestyle in the Gulf today is the role of the dewaniya, a common place for men where receptions are held by local families to socialize and network. It is also a place where business deals are sometimes discussed and even finalized. Dewaniya is a key facet in the construct of communication in this region.

A visual reference from this region’s history, for instance, is sadu, an essential element of traditional material culture for Bedouin women. Sadu is a woven textile that conveys women weavers’ ideas of their rich heritage and instinctive awareness of natural beauty. With patterns and design messaging the old nomadic lifestyle, the desert environment, and the emphasis of aesthetic symmetry and balance due to the making process. This is more relevant to to Bedouins only, though. They are people who have transformed to modern lifestyle, but are still closely tied to their heritage, so you are more likely to see a sadu motif in the Bedouin household.

The problem is that all these cultural references, and others, are repeatedly used in designs in the Gulf without further research. In the example of sadu, for instance, when did it originate? What are the various types of patterns? What do the colors suggest? Sadu is a pattern blatantly added without further exploration, which could inspire other designs. But this is not the case.

Visual elements like Arabic calligraphy; a silhouette of a horse or a camel; and black, red, and white sadu motif have become expected characteristics of design in the Gulf and continue to be.

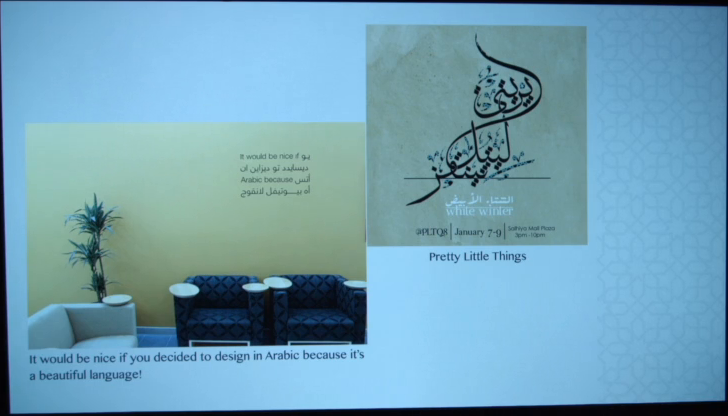

More problematic still is the use, or rather misuse, of Arabic type. Take these images, for example. The image on the left reads “It would be nice if you decided to design in Arabic because it’s a beautiful language!” This in fact Arabic type is used to convey English words. On the right is the banner of an event. Again, the text is written with Arabic type, but the words are English. This reads “Pretty Little Things.” Not only does this undermine the Arabic language, the text is not legible. So if I had no idea what the event’s name was, I most probably wouldn’t be able to read this. And there are numerous other examples.

The Approach in Education

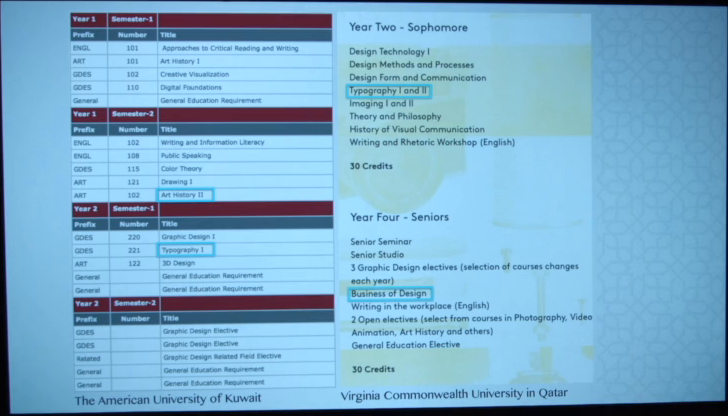

The perpetuation of these visual clichés and misuses stem, I believe, from the way design is taught in the region. Here are the curricula of the graphic design programs at the American University of Kuwait and at Virginia Commonwealth University in Qatar.

Let’s take a closer look. Typography classes are predominantly English-based, with no focus on Arabic. The art history class I studied at the American University of Kuwait, which enriched my knowledge, was a survey of Western art only. Business of Design is a course that teaches a Western business model and disregards the cultural particularity of transacting business in the Gulf, a region where an important phase of a business discussion occasionally takes place at a Dewaniya, as mentioned earlier in this presentation is a men’s-only territory.

Design Education is the Platform

I believe it’s time to explore Khaleeji aesthetics in order to move on from the clichéd repetitions of our cultural icons, and I think design education should be at the forefront of such pioneering work. As long as the knowledge of the Gulf’s history is absent from school curricula in the region, the progress of design here will remain idle and tied to occasional workshops with reference to a remote and vague sense of the past.

However, there is a sign of hope. A distinctive program is offered at Qatar Faculty of Islamic Studies, the Masters of Science in Urban Design and Architecture in Islamic Societies. It is locally-centered, and looks at Islamic culture from a contemporary perspective rather than only historic. It is noteworthy to also look at some other majors this local institute offers: Islamic Finance, Public Policy is Islam. These are considered more conventional disciplines, especially in the Gulf, where the understanding of the importance of design in is still in its early stages. By including a design program, this school acknowledges the equal importance of design as a discipline.

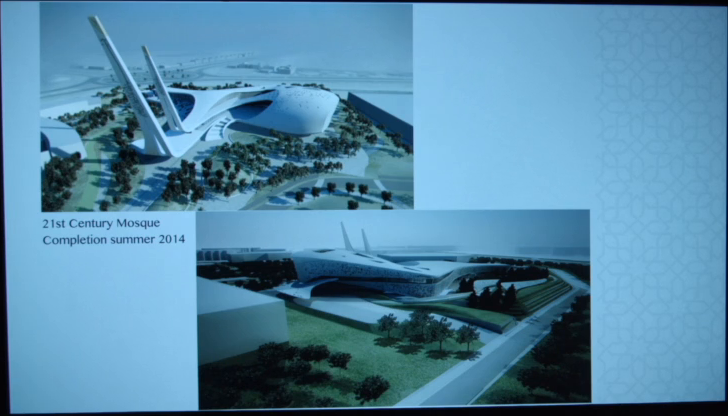

It is also where the 21st Century Mosque is housed. Completion is expected the summer of 2014. A winning design by Mangera Yvars Architects based in London and Barcelona, the main aim of this project is to document Qatar’s advancement in Islamic architecture while introducing innovative design concepts for a modern mosque. Qatar Faculty of Islamic Studies sets the tone with a synthesis of contemporary Western and traditional Gulf aesthetics.

I’ll ask you to take a moment to take a moment to look at the courses offered and realize how they are particularly tweaked to educated design from an Islamic aspect. While it is a post-graduate architecture program, design students from various disciplines could benefit from taking a number of classes offered here like the History and Theory of Architecture, Islamic Civilizations, for instance.

While this is a promising start, there is still much more work to be done. Issues like the unavailability of manufacturing in the Gulf, the lack of resources, the absence of criticism, all hinder the progress of design in the Gulf. These are complex and interconnected issues that need to be addressed.

This presentation has a time limit, but the conversation must continue. Thank you.

Further Reference

Presentation listing at the Lingua Franca conference site, and Nawar’s bio with link to an extract from her thesis.