I wanted to start by establishing where we are right now, right here, today. And I’m going to suggest that we are in the Black Maria. Black walls, black ceiling. Not too much light out there. Who’s this guy?

We are in the Black Maria. And to accomplish the things that we want to accomplish here, we’re going to need both art and science. Who is this guy? We are in the Black Maria. And if you don’t see it yet, you will. Trust me.

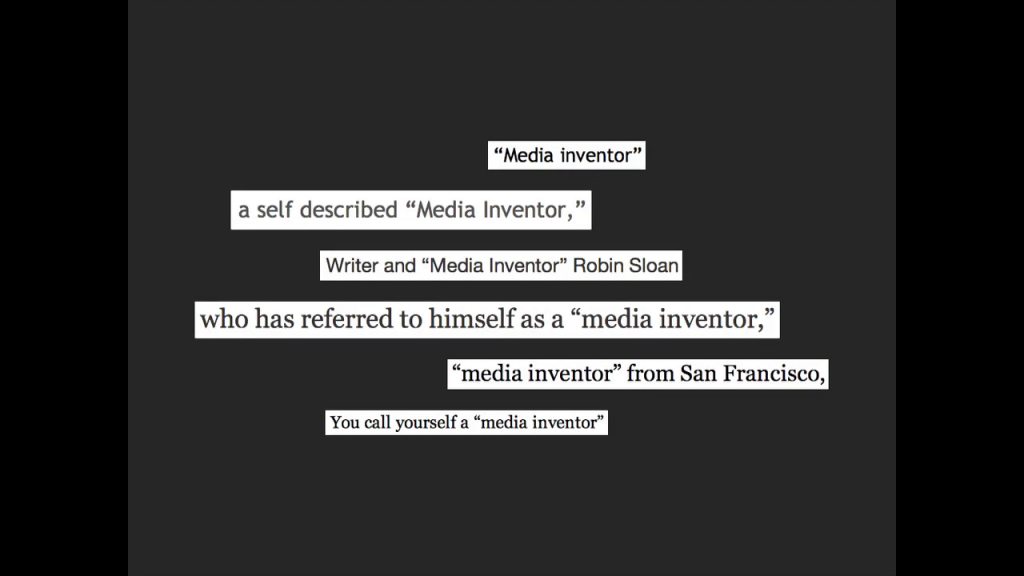

So I wrote this book, Mr. Penumbra’s 24-Hour Bookstore. It’s about an out-of-work web designer who gets a job working the night shift at a very strange bookstore in San Francisco. It came out in the US in October. It’s coming in the UK next year, going to be published by Atlantic Books. And that’s really all I’m going to say about it in this talk. The only reason I’m bringing it up is because along with the publication in the US, there’s been a spate of interviews and little profiles and blog posts and things. And as part of that, reporters always Google me and they find my website, and there they see this

This little tag line on the top of every page. I’m a writer and a media inventor. I basically made that up a couple years ago. I was casting about for some label to describe the mix of things that I do. You know, it’s not just fiction, it’s also things like apps and little experiments that play out on the Web. Things that I write in Javascript. And I needed a way to describe it, the totality of it.

So it turns out nobody can repeat the second part without quotation marks, right. A “self-described media inventor” I think you heard them in the air when Andy said it. “He’s a…‘media inventor.’ ” Robin Sloan, if that is your real name…

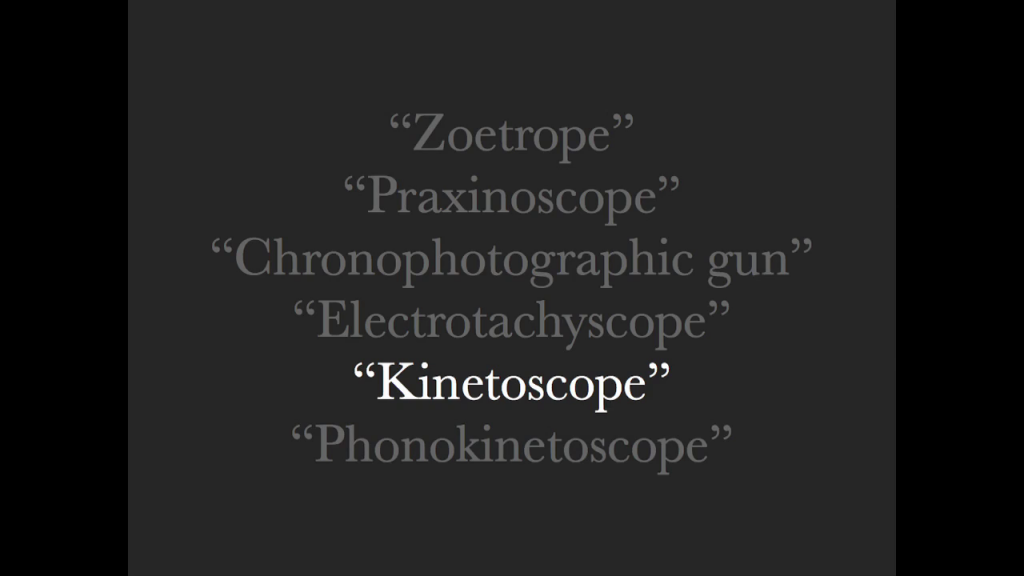

But actually, that’s not uncommon. Quotation marks often serve as a kind of early warning signal. The struggle with language, the struggle to find words, in the sense that they don’t quite fit for a long time, is actually totally common. Anytime on you find people working with strange tools or combining familiar tools in strange ways, you will often find quotation marks. You will often find them I’m struggling to come up with the right words to describe whatever it is they’re doing. And then of course questioning the words they’ve chosen.

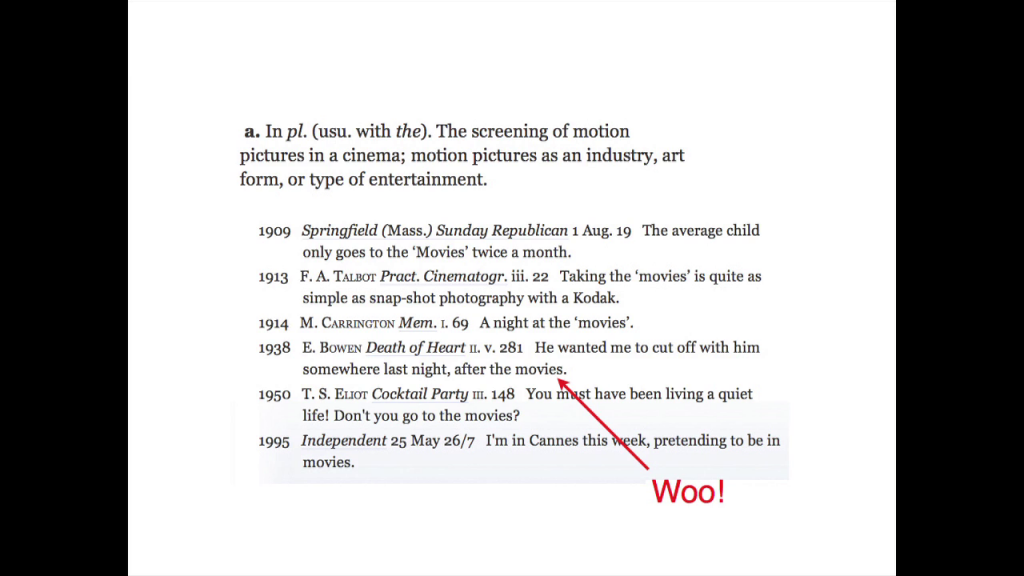

My favorite examples of that in history is movies around the turn of the last century. Of course, circa 1900, they were actually still “movies.” If you look in the Oxford English Dictionary at their great sort of timeline of usage, you’ll see it. You’ll see the maturation of this medium, and the maturation of this word. The first reference to movies comes in 1909, and it’s not until sometime between 1914 and 1938 that the apostrophe finally drops. It’s like, “Okay. Maybe this thing will actually stick around. Maybe these ‘movies’ are actually good for something.”

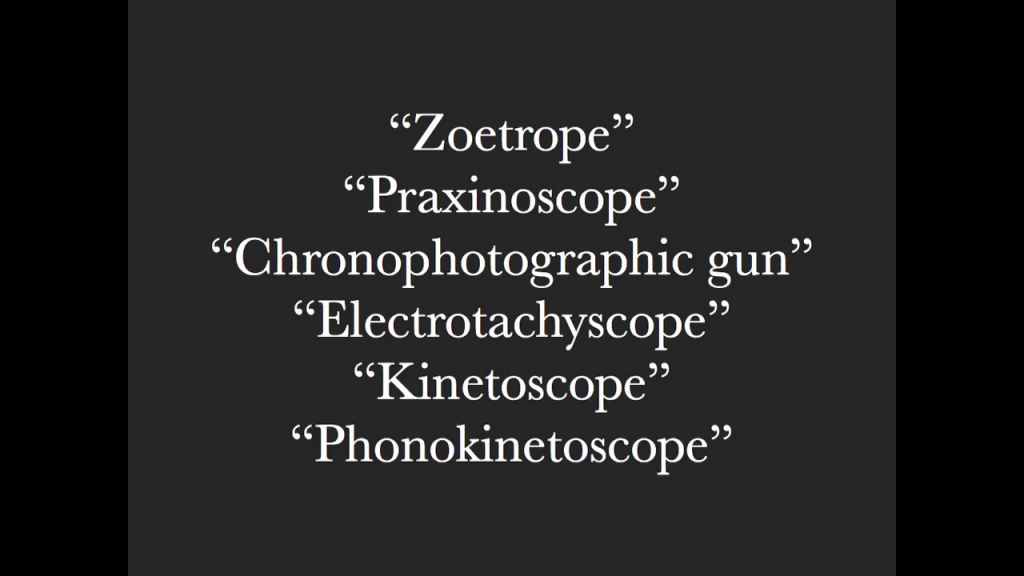

Before that, closer to 1900, nobody knew what to call anything in the movie industry. Every word was made up, every word was in quotation marks. From the vantage point of today, it looks sort of ridiculous. But these words, they represent a real struggle. These people were doing something new. They were in uncharted uncharted territory, both mechanically and creatively. I mean, what’s a cronophotographic gun? Can anyone guess? It’s actually the most circuitous way imaginable to describe a movie camera. But of course in 1900 they didn’t have the word “movie.” And they also didn’t have the word camera, at least not applied to moving images. So you’re like, “Well, it’s this thing, you shoot it, you point it, it takes theses pictures…” Suddenly, cronophotographic gun doesn’t sound so bad.

They were still so far away from the stability of a word like “movie.” Now, today of course the quotation marks are long gone. Movies have settled in. They’re not fixed. The content of movies is still changing, things like the 3D are emerging. But they’re definitely mature. Especially if we work on digital products, we build and design around movies I’d argue that we take the movie as sort of a black box.

What’s in the box? We all know this. It’s a sequence of video, between 90 and 140 minutes. The video is 1,920 pixels wide. Video uses techniques like cuts and close ups. We know this. We know these specifications. And we know these words.

The movie, the black box, is always represented on the screen by a rectangle, roughly the shape of a movie poster, always. It’d be ridiculous if you made a web site or application that showed movies as circles or ovals or squares. It’s funny actually. As a sidenote, isn’t it funny that these might be books, they might be movies. But these are definitely albums, right? Always and everywhere.

In iTunes, on Rdio, and everywhere else. Echoes of the past. You can kind of see the ghostly CD, the ghostly LP, lurking inside that perfect square. I love those little conventions.

So anyway, it’s possible to do great, useful, interesting, rewarding work around a stable, mature format. Of course it is. But. Don’t you think it’s a shame to leave these boxes black? To cede that creative space to other people, most of them long-dead? I want to convince you that it is a shame. The practice of cracking open the black box and building new boxes altogether is real, and it has a name.

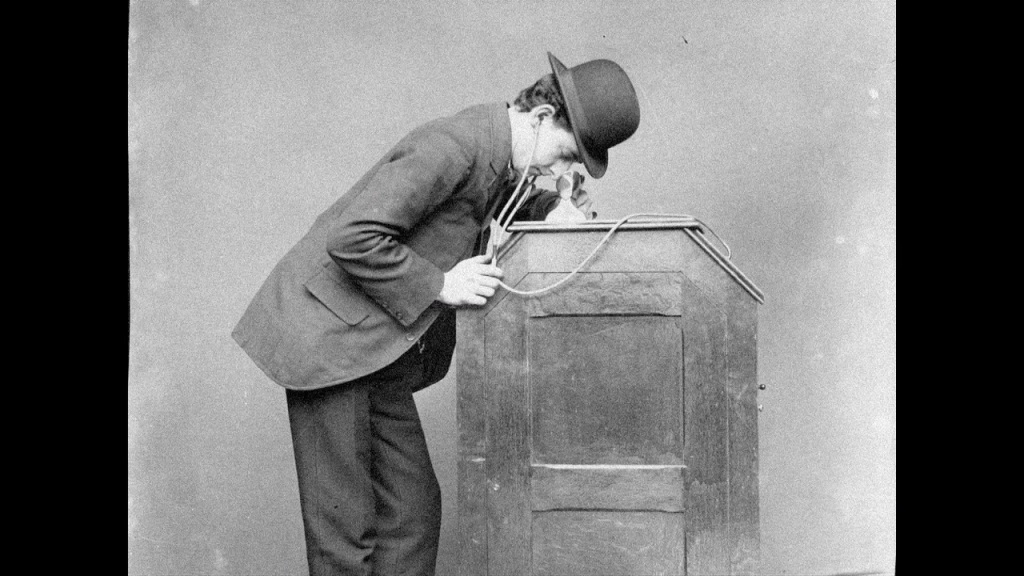

So, back before “movies” dropped its quotation marks, back in the era of the cronophotographic gun, there was one format that broke out ahead of the pack, one of these words that actually got some traction, right around 1900. It was Thomas Edison’s kinetoscope, which was mostly the work of his employee William Dixon. And you can think about it this way. Edison and Dixon had built a kind of primitive movie camera. They developed a way of playing back what they recorded. So they had all the pieces of the puzzle. They had, in fact, built this brand new box.

And it really was a box. This is how it looked. This how it worked. You would go into a “kinetoscope parlor” and see what was playing. But they didn’t know what to put inside the box. Not yet. So they just tried everything.

They tried athletic demos. They tried beheadings. They tried boxing cats. This is one of the first videos ever made in history. I still think that guy in the back is one of the creepiest things ever committed to film.

You can feel it, right? You can feel that Edison and Dixon know they’re on to something. They know this technology is really exciting, but they have no idea what to do with it. So what we’re looking at here is creative R&D. These are creative prototypes. This feels like such fun to me. I think it must’ve been fun. And that means it’s fun right now, too. Because we too are in the Black Maria.

Who is this? Today in 2012, right now, sitting in this space, all of us. We are in the Black Maria. Do you see it? You will.

Let me make this more concrete. I’m going to move from 1900 to 2012. I’m going to share my own personal tale of media invention. I should start by saying, or establishing, that these are pretty popular, obviously. Perhaps especially among the people in this room. I am specifically interested, almost obsessed, with the creative possibilities of screens like this. I think there are ways to tell stories, to make arguments, on this kind of screen, with its beauty, intimacy, its sort of tactility, that are truly new. Like, truly world-historically new. And I think stories told on the screen could compete with all those other black boxes. You know, with movies, books, and albums, all of it. They could compete for our attention. They could compete in the arena of culture.

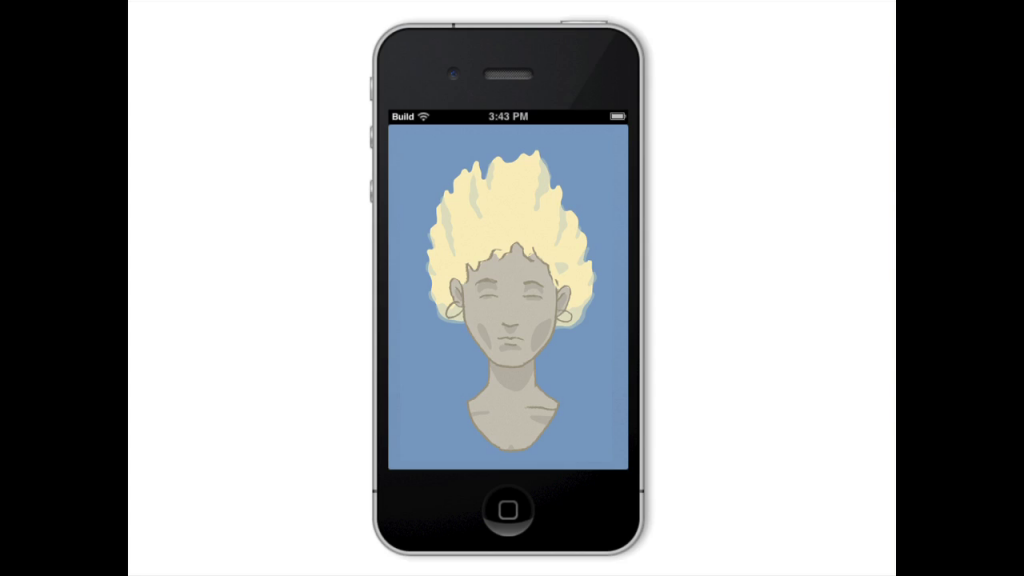

That’s what I believe. So I decided to give it a try. At the beginning of this year, I sketched out a retelling of the myth of Orpheus. Remember, this is the one where Orpheus’ lover Eurydice, she dies. Orpheus is heartbroken, and he won’t accept it. So he goes down into the underworld (as one does) and he plays a tune for Hades. He’s the best musician of all time so Hades decides to give him a break, and he agrees to release Eurydice. On one condition. Orpheus has to lead her back up to the land of the living without looking back. So, nervously he starts the climb. If you don’t know the story I won’t spoil it for you. It’s very dramatic.

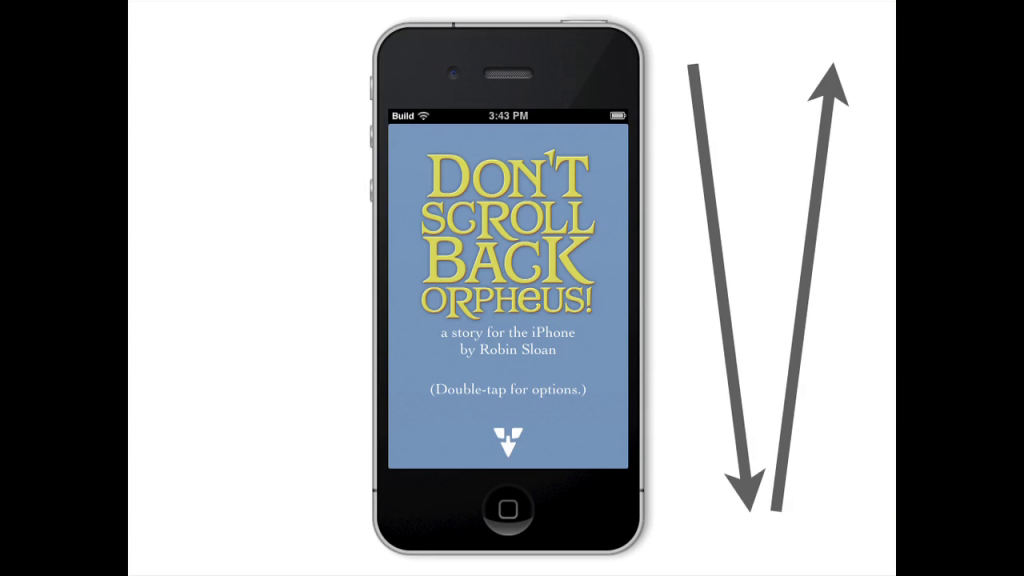

This is what I made, Don’t Scroll Back Orpheus. That was the title. And this is perfect, right? Form meets content on this kind of device. You scroll down for the first half of the story, following Orpheus down into the underworld for his confrontation with Hades. Then the scroll direction actually changed, and you went back up. And it really did feel like claiming. It was harder to make your way back up through the story. Form meets content. I was so excited about this.

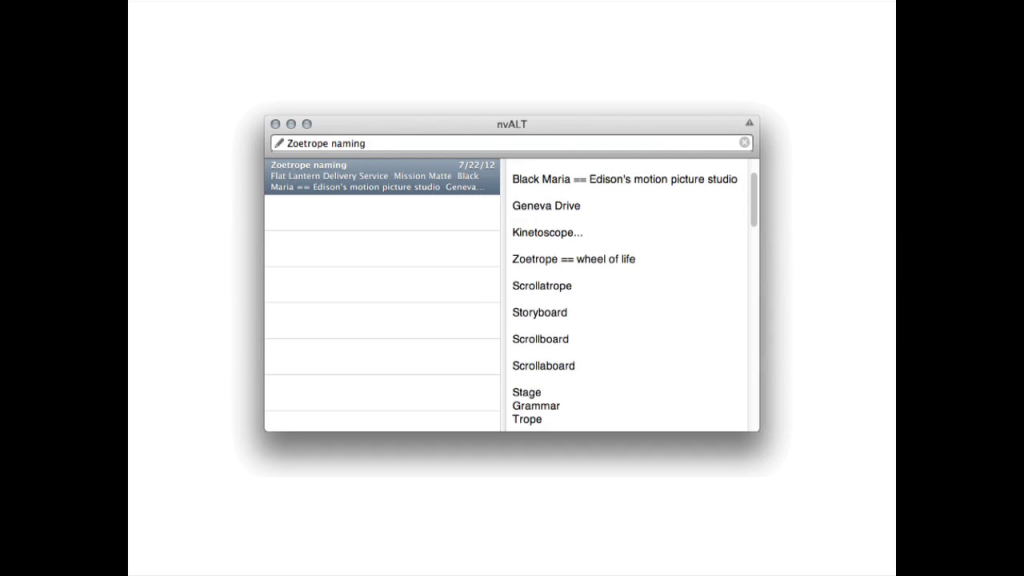

I found this page from my notes where you can see I’m deciding what to call this amazing new format. The scrollotrope, the storyboard, the scrollboard. Clearly this is going to be so popular that it needs a name immediately. I better figure it out fast.

As it turns out it did not need a name. Because it didn’t work. It was like those videos, you know. As a viewer, you kind of look at it and you go, “I get what you’re trying to do there, but this mayyy not be the future of entertainment.” I put this thing together. I showed it to a few people. And everybody went, “I see what you’re trying to do here but…it’s not that good. Not yet.”

So then I went back to the drawing board. And I can’t say I did so armed with any great insight or revelation. I just knew one thing that didn’t work. I still didn’t know what would work. So I just tried again. I started a new story. Actually, this time it was more of an essay. It was about the limits of attention on the Internet today.

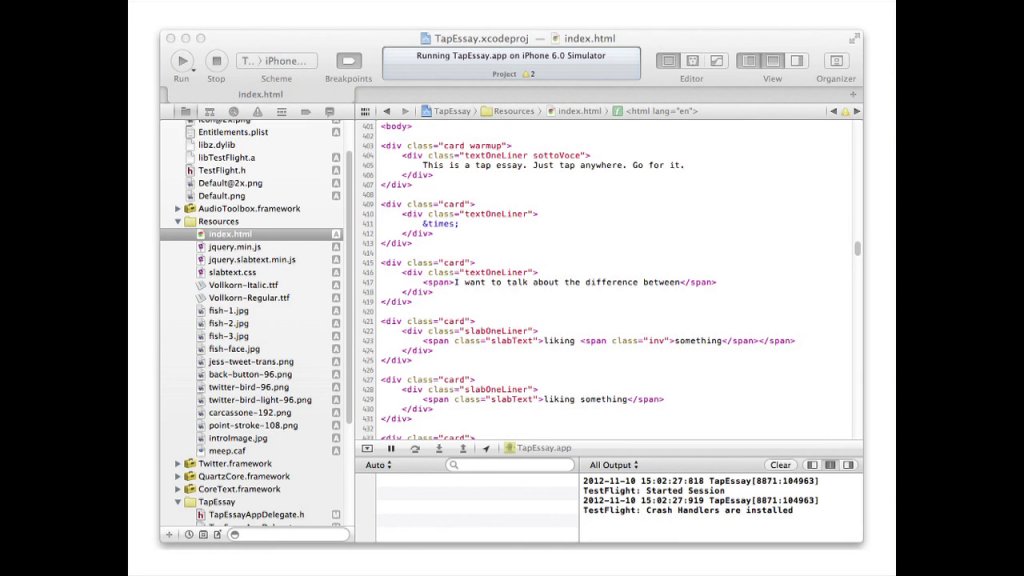

Here’s the project in Xcode. I wrote the text and I built app together at the same time, just as I had done with with Orpheus. I’d be writing, I’d think of something I wanted to do creatively, and then I’d implement in Objective C. I’d run the app again to see if it had worked. Often, it didn’t. So I’d take it back, I’d try something else. I’d do this again and again and again. Compile and recompile and recompile. Read and reread and reread.

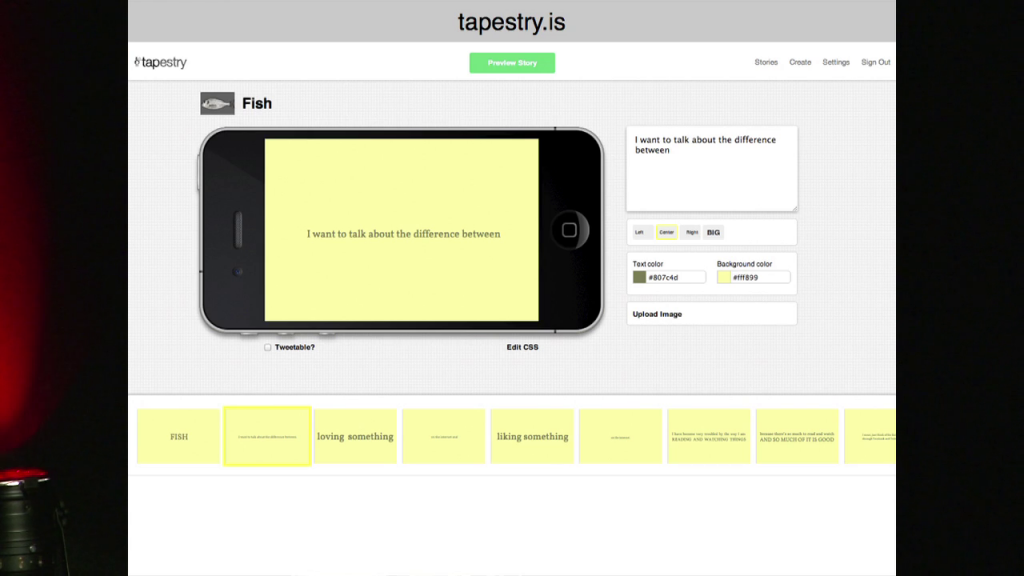

The result of this process was an app called Fish that some of you might have used, you might’ve read. You can download it for free in the App Store if not. It starts like this. It kind of announces itself first thing. I opted against quote marks but you know, I probably should’ve included them. “This is a tap essay. Just tap anywhere. Go for it. I want to talk about the difference between liking something on the internet and loving something on the internet.”

The main thing that distinguishes this form, I think, is the way the sentences are broken up like that, sometimes down into phrases, sometimes down into individual words. It sort of lends the reading experience the rhythm of speech. So this time, I showed it to some people, and it worked. They liked it. It was actually really cool. And I had no idea what to call it at first. Definitely not “scrollotrope.” It’s actually where I came up with “tap essay” and kind of put it in after the fact.

It was a great success. Many people downloaded it and talked about it, both its form and its content, which is kind of exactly what I was after. And even today, months and months after it was originally released, people are still tweeting from inside the app, sharing and resharing these pithy little lines they’re discovering there.

So, after I released this first “tap essay,” of course, I thought, “I’ve gotta make another one.” Or better yet, “I gotta make a tool to help other people make these.” This could be a brand new box. This could be a new format. The tap essay. One day the quotation marks might even fall off.

But I couldn’t do it, you know. The apps’s code was bound really tightly to its content. And I’m not actually a very good programmer, and I had a novel to finish. And then I got lucky. A guy named John Borthwick at Betaworks in New York was a fan of Fish, and he believed that it was a new format, or something on the road to a new format. So he built a little team which included a super-talented designer and developer named Patrick Moberg.

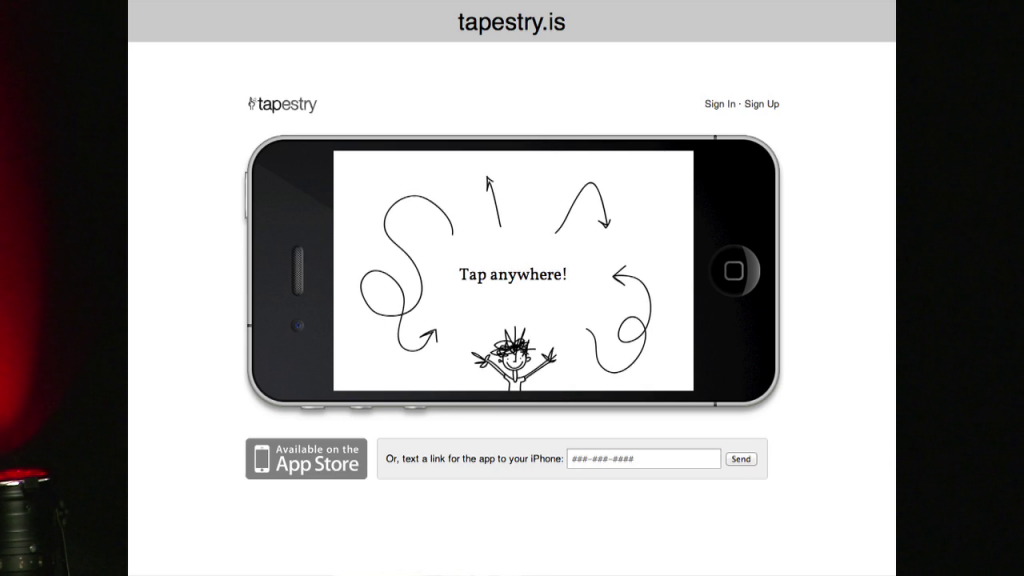

And in a matter of months Patrick cranked out this. It’s called Tapestry. This is live on the web today. It just launched a couple weeks ago. It’s at tapestry.is And it’s a platform for tap essays. Or “tap stories,” actually, as Betaworks is calling them now. Quotation marks still very much in effect. And, you know, it’s awesome. You can make new tap stories, you can edit them, you can see them all laid out. You can sort of see the shape and the structure of these things that used to be totally obscured in code and nested HTML tags. And this is exciting because it means now the work can really begin. We can start to understand, is this really a new format? If so, what are its properties? What are its physics?

I have some guesses. I have some opinions of my own. For instance, I think rhythm is crucial to a tap story. The rhythm of the words and how that rhythm is expressed in the reveals. I think a good tap story is actually more like a speech than it is like a blog post. But who knows? I mean, I don’t actually know any more about this format than anybody else. It’s brand new. It’s fair game.

So that’s a tiny bit of modern media invention. This is a far cry from the kinetoscope, but it is at least a complete arc from notion to failure to prototype to format. Repeatable and explorable. There is now this new little box, something called a “tap story,” that other people can fill up with words, pictures, ideas. With stories.

So why do this? Why bother with anything like that? Well, I think that’s pretty clear, actually. You know, in 1900, Edison and company saw this magical new thing, the recording and the recreation of moving images. They saw that it was possible for the first time. Now, they did not foresee what it would become. They did not foresee Citizen Kane. They did not foresee the BBC’s Planet Earth documentaries. They did not foresee Back to the Future. But they knew there was something there. They knew there was something possible. So they worked hard. They rustled up some boxing cats. And now we owe them a debt of gratitude for all that has followed, all that they could not have foreseen.

Well, I think today we, too, find ourselves with something magical. We have these beautiful, intimate, tactile screens that’re all connected to the internet. There’s something here. And therefore, I think, by power of syllogism, there must be creations just as wonderful and unforeseeable as Kane or Back to the Future waiting in our future that we cannot see, that we cannot imagine, but that we can begin. We can be their progenitors, if we choose.

So who is this guy? This is Fred Ott. He worked on Edison’s team back in 1900. And he is the star of the greatest of these weird little videos. It is a kinetographic recording of a sneeze. And this is actually the first copyrighted movie in history. Edison and his team recorded this on their kinetograph. They printed out the frames, and they submitted them to the Library Congress, and it had the title “Record of a Sneeze.” They had no idea what they were doing.

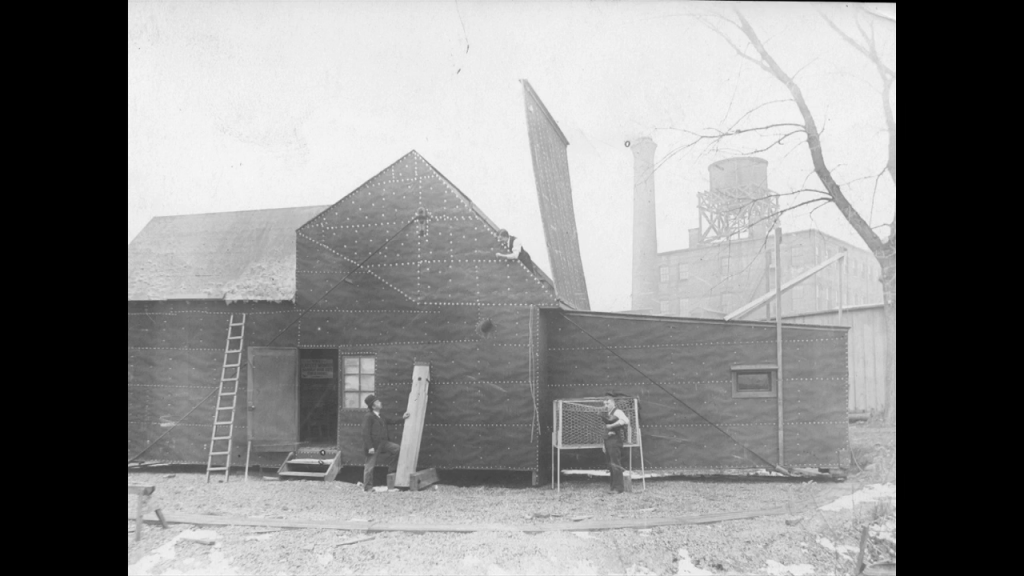

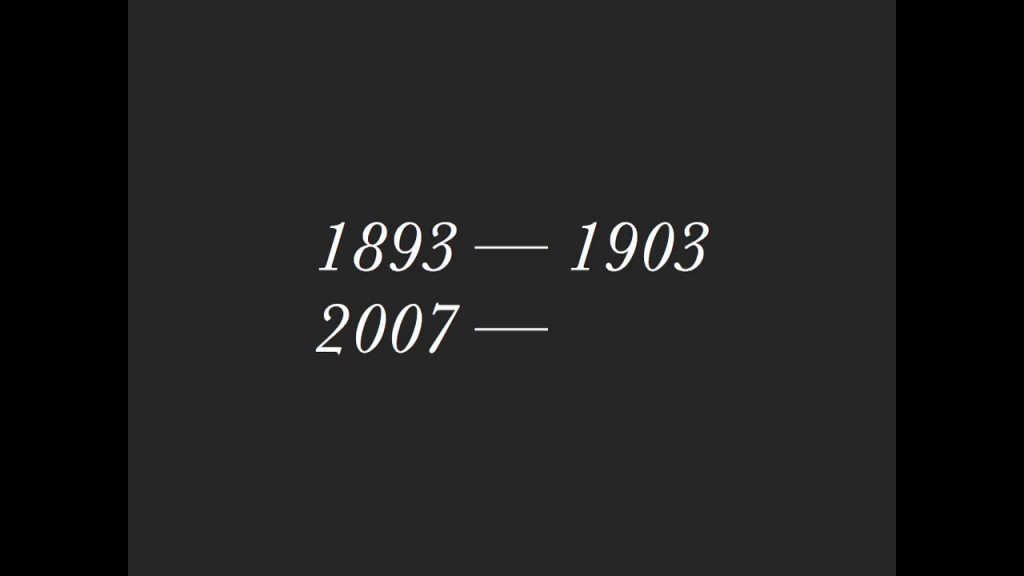

Fred Ott sneezed here. This is the Black Maria, at last. This was Edison’s movie studio. In fact, it was the first movie studio. They called it that, the Black Maria because it was big and black and sort of shaped like a police wagon, maybe. Those were called Black Marias at the time. I think it probably tells you, more than anything, else about Edison’s relationship to his employees. They felt trapped, perhaps. They built this place in New Jersey. It cost about sixteen thousand dollars, in modern 2012 dollars, to build. And was totally a pile of junk. I think you can you kinda tell by looking at it. Basically a big shed. The walls were all just covered in tar paper. This is where they filmed all those early videos. You know, they brought them all here, the athletes, and the actors, and yes the boxing cats. And they went to work even though they obviously had no idea what they were doing. They just tried things, again and again, for just about ten years exactly. They did it all here, in this cramped little laboratory.

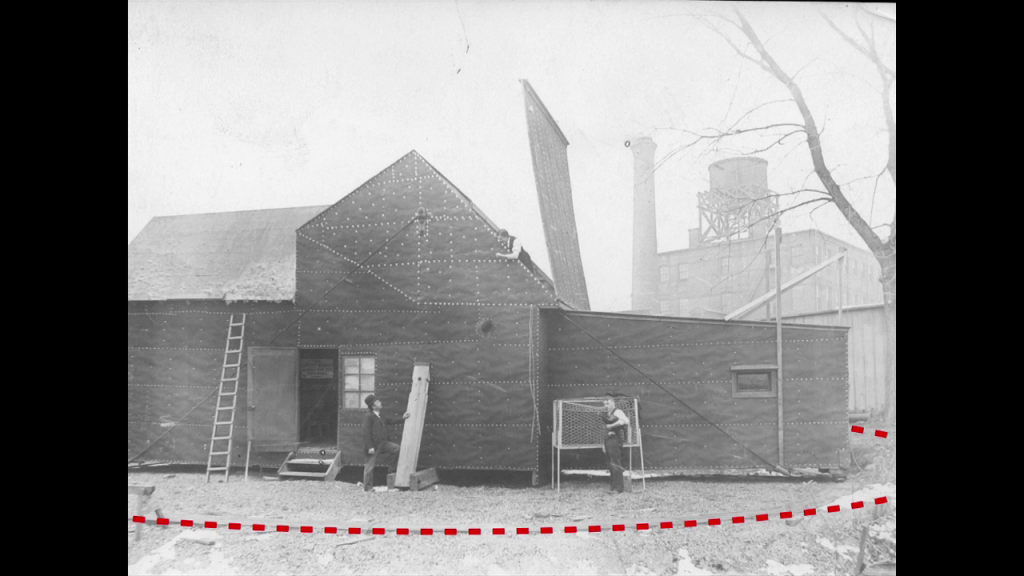

Can you see that faint line, that sort of track in the dirt? The Black Maria was built on a rotating platform. The kinetograph needed a ton of light to operate at all, so they would open that big panel on top and then they would just turn the whole building to face the sun. Which is so janky. And wonderful. I’m sure that some people in this room have made technical decisions basically equivalent to putting the whole building on a rotating platform so it can face the sun. And that’s okay.

What were these guys doing there? They were inventors in the classic sense, sure. They were building crazy machines. But they were making the content at the same time, and I think that’s important. Inside the studio, there was a pile of gears and lenses. But outside the studio, there was a long line of actors and dancers, maybe a few stray cats. And all of that worked together. They were not just inventors. They were media inventors. No quotation marks. This is real, and I think it needs a name. If a guy in 1887 could call something the electrotachyscope and get away with it, I think I can get away with calling these guys media inventors.

And this is what I want to be. I don’t actually think I am one yet. I don’t think I’ve done anything worthy of the name. But this is my ambition, you know. This is my lodestar. And if any of this sounds interesting to you, I invite you to use the term, too.

The truth is you might already be a media inventor without realizing it. For instance, you might be a media inventor if: You don’t quite have the words to describe what it is you do. If you struggle with language to describe your preoccupations. If you routinely feel dumb, sort of stammering, about a possibility that you can see so clearly.

You might be media inventor if you tend to toggle back and forth between technology and content. If you work on ideas and code together. Especially if you love both. If you appreciate the particular pleasures of each. If you find yourself drawn to both, even if it’s clear that you’re way better at one than the other. If your talents are lopsided… Maybe you’re great programmer but a bad writer. Maybe you’re a great writer but a terrible designer. It doesn’t matter. Talent has very little to do with this.

You might be a media inventor if you’re working inside the black box. If you feel perhaps not quite creatively satisfied, shuffling and reshuffling a deck that was created decades before you were born. If you think you might be interested in making a new format.

We are in the Black Maria. Can you see it now? Can you feel it? The future, just out of sight, still in quotation marks, forever trapped in quotation marks, but nevertheless being fashioned right here, in the dark.

We are in the Black Maria. Edison and his crew spent ten years in that shed before they finally upgraded. They moved to New York City and they had a beautiful glass studio built there. When they upgraded, the word movies still didn’t exist. We’ve had these [holds up cell phone] for about five years? So we’re right in the middle of our time in the shed. And when that time is up, we will not have come to the end. No way. We will in fact finally be at the beginning. We’ll finally be ready to find our own “movies.”

Here we are. It’s hot. It’s cramped. It’s stuffy. The wheels keep getting stuck when we try to turn the whole building around. We’ve been up all night. There’s a guy out front with a ferret who he’s taught to play a tiny trombone, and he wants us to put it in front of the kinetograph. And you know what? We probably will.

Right now in 2012, working with screens, telling stories on these new devices, I’m convinced we are in our own Black Maria. And I think it’s a wonderful place to be.

Thank you.

Further Reference

Robin Sloan’s home page