Ingrid Burrington: Hi, everyone. Thank you for coming. It’s really humbling to be here, and thank you Addie for inviting me.

So, hi. My name is Ingrid. I’ve been using, a lot of times, as my one-liner artist statement that I make maps and tell jokes. Which is to say I think a lot about power, given that maps and jokes are tremendous instruments for exercising, explaining, and challenging power. And I’m going to just be talking about some work that I’ve been doing for the last eighteen months that started with what I think of as an image problem. When stories about online and phone-based mass surveillance started rolling out, the stock photography was really weak. And the images all seemed to not really capture, to me, what we were actually seeing happen. There were a lot of white dudes looking at screens and a lot of blue-filter, Eye of Sauron shit. And part of this problem is that it’s an abstract thing, right? But the other part is that the parts that aren’t abstract, like the actual places where surveillance takes place, the kinds of images that you can even get are sort of limited.

This is probably one of my favorite photos I’ve ever taken. It’s at a park next to the NSA. It’s for famous fallen spy planes, and not only does it have a list of things you shouldn’t take a picture of, it has a picture of the kind of picture you can’t have. So not only does the NSA have really strict rules about what kinds of images can be put out about it—there’s like that one famous stock photo and then [Caitlin?] made another one—they also have control over an image that is impossible to create.

And then one of the other things like that Eye of Sauron clip art thing I think does is it amps up the mystique factor, and I think kind of adds to this idea that these institutions are impenetrable. This is a mousepad that I bought at the Cryptology Museum next door to the NSA, and um, they can’t summon lightning. This stuff, I think it kind of feeds into a culture of fear around this stuff. And I’m really into exposing the banality of power, the way in which a lot of these things that are kind of sensationalized or terrifying are really just white dudes in suburban office parks. And I started with looking a lot at one particular office park.

So this map, down at the bottom, that’s the NSA. And then a little further to the top and to the left, that is an office park that I first started noticing. I went down to Fort Meade for Chelsea Manning’s trial and was just looking around at things that were in the area and saw all these defense contractors in this office park and was like, “That’s…inevitable.” It turns out this property, which is called The National Business Park, is owned by a real estate investment trust called Corporate Office Properties Trust, and their entire business strategy appears to be “buy land next to major defense outposts, and build offices for defense contractors and the government.” Which is actually a pretty smart business strategy if you’re a real estate company.

This to me, this is where surveillance actually happens. So much of the work that is being done by the government is actually being done by third parties, and it’s a very lucrative business. So I went to this office park and kind of just walked around it, and it’s boring. It’s really kind of weird and boring and it’s weird to think about the fact that these companies that are enormous and involved in pretty unseemly shit appear like this, like this kind of crappy building with this kind of crappy public art. And at the same time, there’s all these sort of little hints to what is actually there. Like, there are certain roads that you can’t really go much further past on without needing to show specific kinds of ID.

I was interested in trying to use that specific landscape and maps of it as a way to see how the military-industrial complex has become increasingly privatized, so I started looking at Landsat satellite imagery. So this is an image of that office park in 2002.

That was the oldest one that I could find. It’s kind of tiled together. So there’s a couple buildings there; they’re currently doing okay. This is 2006.

It’s not a perfect transition, but you can see there are at least a few more buildings. By then there’s about eight new buildings that’ve been added to this. What happened between 2002 and 2006? The obvious one is that we invaded Iraq, but the other one in 2002 was Project Trailblazer was started. I don’t know how many people here are familiar with Project Trailblazer. It was a giant information surveillance program that was contracted out to (I have to always write this down) SAIC, Boeing, CSC, and Booz Allen Hamilton. It was a complete boondoggle. And this was the project that a number of whistleblowers inside the Department of Defense brought to the Inspector General because the NSA could’ve built it themselves for a lot less money. And this is why Thomas Drake was indicted for the Espionage Act.

This is the property in 2012. There’s another million square feet that’s been added since 2006, there’s nine more buildings. So this is a very small but very interesting illustration to me of the fact that the military-industrial complex isn’t just weapons or malware, it’s real estate. It’s property, it’s bodies, it’s humans.

One of the things that I thought was super-interesting as I started looking into this particular real estate company was that they had started this business pivot to running data centers. Which of course is extremely smart. But it led me, in trying to go see their data centers and other data centers, into this kind of misleadingly banal question, which is “How do you see the Internet?” And I guess this is how most of us see the Internet, like we’re interfacing with it:

But when you try to actually explain to someone what the Internet is, or how to comprehend it, you get a lot of really abstract network diagrams and really misleading metaphors and clip art. (Don’t get me started on the cloud.) Cuz like, this is the cloud:

This is an Amazon data center in Northern Virginia and it’s not calling attention to itself. It’s kind of a crucial piece of infrastructure, and it’s something that you would never really even really notice.

So at this point in the year I started to get really obsessed with network infrastructure. This is what happens when you start talking to people about network infrastructure, I have learned.

And I completely understand why, because it’s something that was sort of designed to be ignored. You really only notice infrastructure when it stops working. We can get into whether there is something about the Internet that is no longer working perhaps later. I should probably just move on to a little more of methods.

So it turns out if you want maps of where fiber lines are and want to get a better sense of data center geography, people won’t just tell you. So I kind of had to figure it out myself. And I started out really small. I just wanted to figure out “how can I see the Internet within one city block around me, like walking down the street in Manhattan?” Turns out a really good way to do that is to look down.

I imagine you’ve seen things like this before walking down the street, like spray paint on intersections and streets. This is stuff that’s put down on the street prior to street excavation work, and it’s basically a way for people doing that work to know what’s around them, so that if they’re going to be doing work on a gas line they don’t accidentally cut the power to an entire neighborhood.

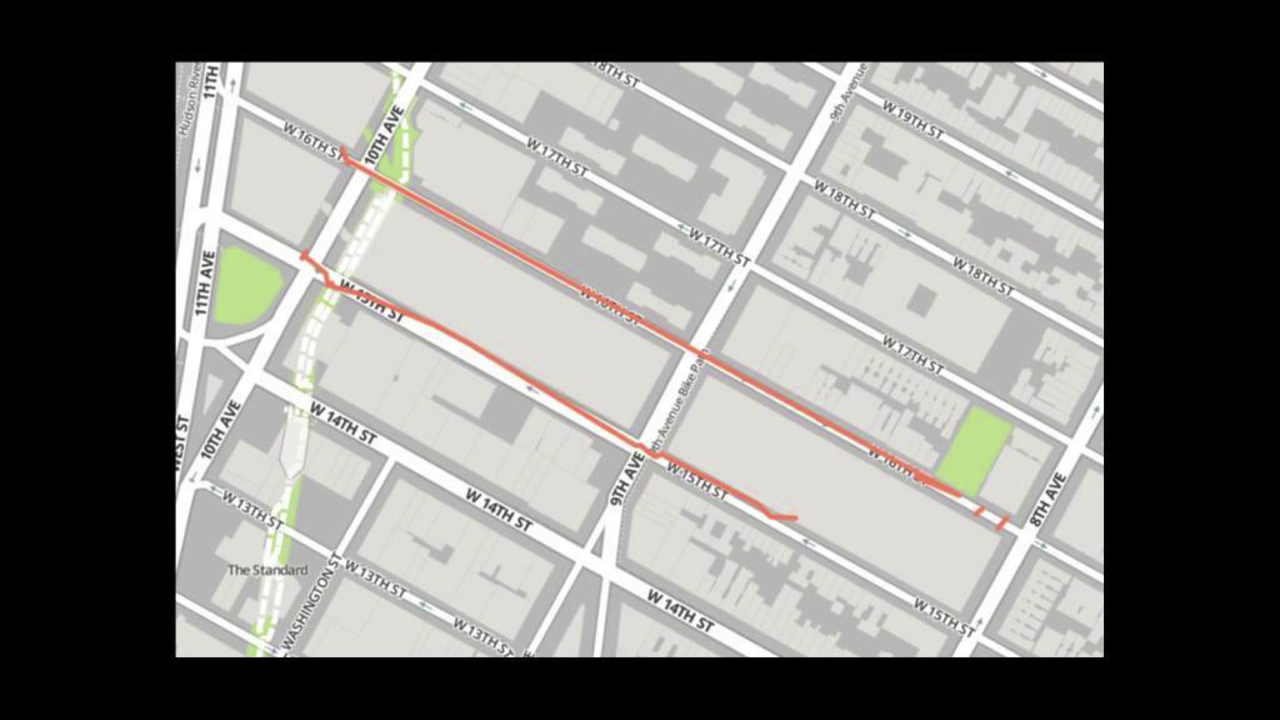

They’re all color-coded, there’s an international standard for this. And all the orange ones are telecommunications. That includes telephone and TV and well as internet. But once you start looking for these, you really can’t not see them. I kind of started to think of them like The Crying of Lot 49, like you could just find the postal horn everywhere. And there’s some fun things you can do with this, so like this is a weird way to kind of reverse engineer where certain fiber lines are.

These are two lines that are running out of 111 8th Ave, which is a major carrier hotel, into 85 10th Ave., which has a Level 3 colocation center. (Fun fact: also home to the FBI Joint Terrorism Task Force offices. IDK)

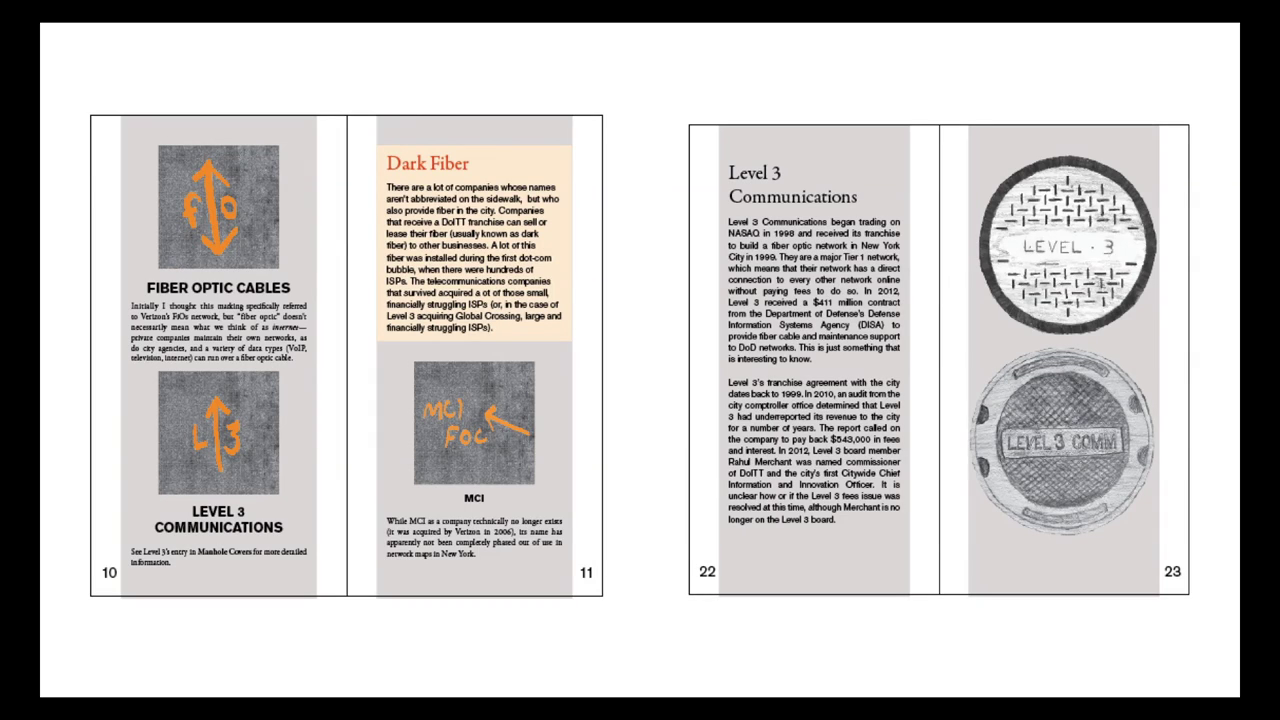

But that’s a very tedious way to work through that problem, to try and walk through the entire city, following orange lines, and eventually I’m going to get hit by a bus. So the other way that I’ve been approaching this problem is by working on a field guide, so that anyone can figure out what these things are, and what they’re looking at, and see the Internet on the street. And this is going to be printed in January. It’s also a weird way to get in a lot of sideways information about the politics of network infrastructure. In this slide there’s an aside about dark fiber. What is it? Why do all these ISPs have it? Why do they sell it for so much money to banks? A version of this also exists on-line, so I’m a little more into the idea of a hand-held experience with it. But if you’re interested, it’s out there.

One of the things that a lot of this work has made me think a lot about is scale. There was a time computers used to be the size of an entire room to function. And while we’ve been able to make hardware that is smaller, I believe that the room has simply gotten bigger, to about the size of the planet. We’re surrounded by sensors everywhere, and a lot of them are fairly mundane, and a lot of them we can kind of easily forget about and have been there for a long time. I think sometimes I get a little side-eye at the hype over the Internet of Things because we’ve had this shit around for a while. And then there’s elements of it that’s kind of insidious and is kind of working as private networks that we can’t really understand and that are increasingly actually on human bodies.

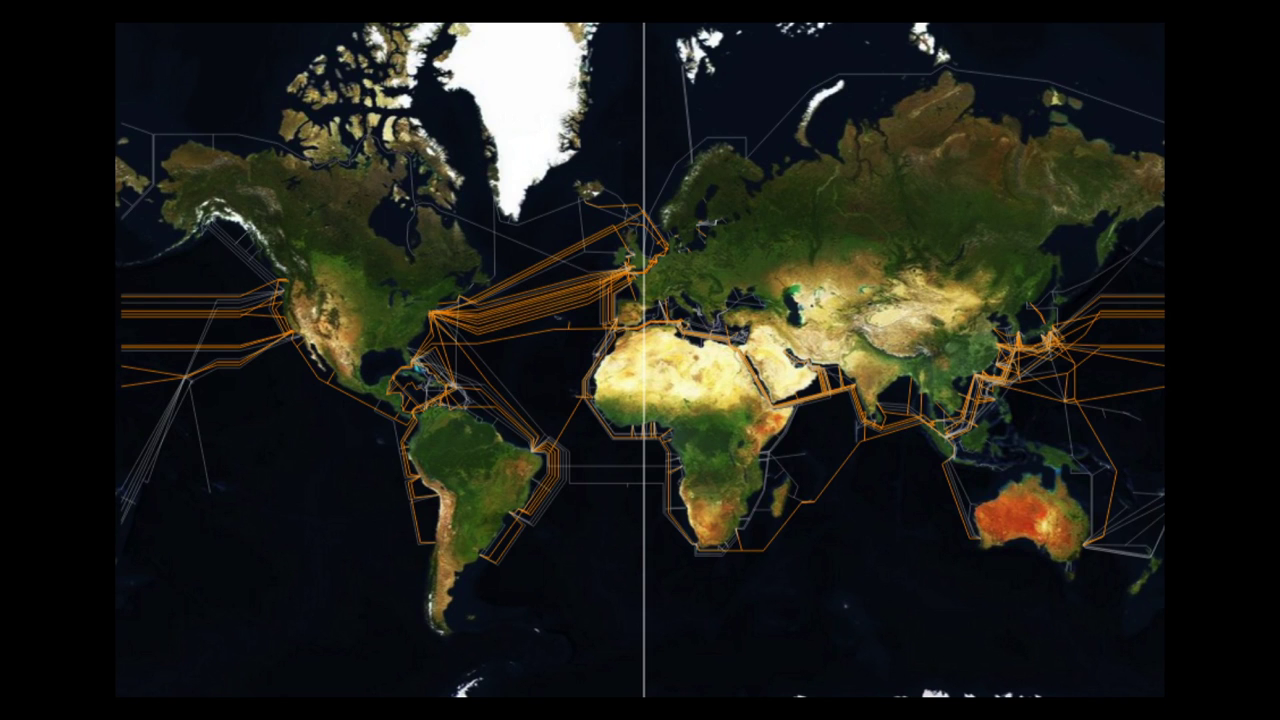

This next slide [screenshot of this article] is going to seem like a detour, but it’s actually just taking the scenic route to a related point, so bear with me. This is a small project that I finished very recently and is kind of related to what I’m trying to work on next while I’m here this week. A couple of weeks ago, a German newspaper released a story about GCHQ’s tapping of some submarine cables, the cables that connect ocean Internets to each other. And this wasn’t new, like people had known that they were doing it, but this was the first article that released a document that had a list of exactly which cables, which happens to be pretty easy to find public information, like just the existence of where cables are. Telegeography maintains a really nice data set about them.

So I just kind of mashed those together and made a map of which cables are being tapped and which ones aren’t, and which programs they’re associated with, and which companies own those cables because that can also give you a sense of what these codename programs, who the partner associations affiliated with them are.

Our Command & Control Networks are truly being transformed into a WEAPON SYSTEM as they get leveraged more and more by our soldiers — and as such, need to be protected from the increasing focus and efforts of our enemies to attack them using any & all means…

Defense Information Systems Agency NetOps Strategic Plan 2006

This was a quote from a Department of Defense document that was essentially making the argument that communication networks are weapons systems. Literally, not like they’re a means to an end, they were basically like, “Communications systems are weapons.” And to me this illustrates a certain urgency for why you might want to care about infrastructure, and might want to know about fiber lines beneath your feet, because they have been weaponized. They have been militarized. And it would be cool if we could make them less that. And what I’ve been thinking a lot about this week is how to follow a thread that connects you from the massive military-industrial networks that are capturing information and separating networks all the time.

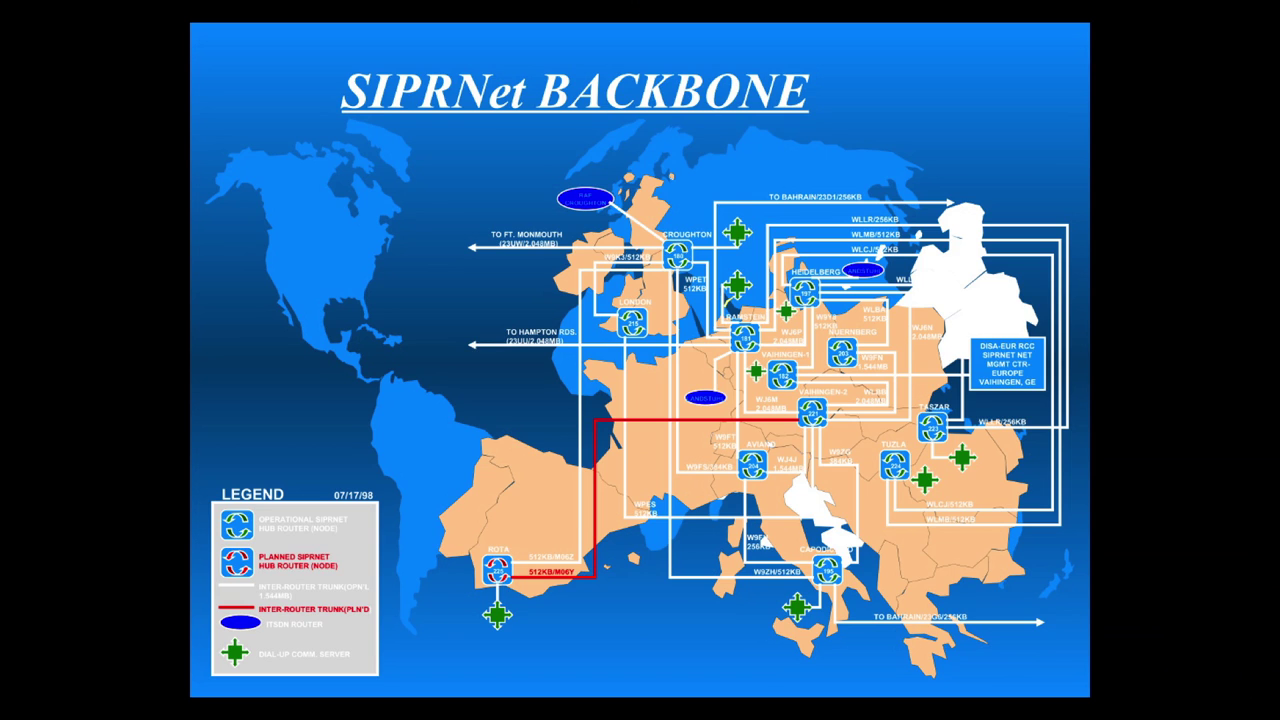

This is a 2004 map of the SIPRNet, which is the Secure Information Protocol Routing Network; it’s the Department of Defense’s private classified network that spans a huge amount of the world. Connecting this to police departments that now are able to collect cell phone data of protesters. There is a link that is bringing things from this really high level, from submarine cables, down to the street, back to that intersection where you’re just trying to find the Internet.

I don’t totally know what that looks like, and I’m hoping to figure it out, and I don’t want to think of it as a demoralizing point. I think it’s a challenge that has to be taken on and is worth taking on. Thank you very much.