During the war in Afghanistan, the military decided to air drop food packages as part of its winning hearts and minds campaign.

Unfortunately, the food packages were very similar in appearance to the cluster bombs they were dropping at the same time. If military decision-makers had spoken to communities, aid workers, military personnel on the ground, they’d have figured out there were smarter ways to deliver food and win the trust of the Afghan people. Listening to those who live a particular problem is essential to effective policy. I’m gonna explain why using two examples. First, the ebola outbreak in West Africa which began in 2014.

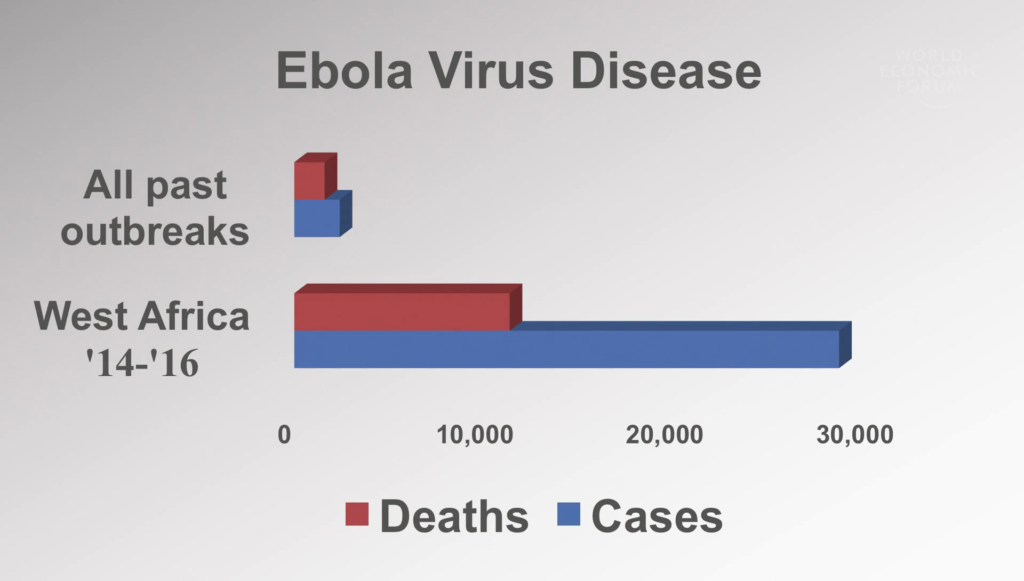

Ebola is not a particularly contagious disease. If those who become sick or die of the disease are cared for safely and buried safely, you can stop its spread. It’s how we’ve dealt with ebola in the past, and it was it’s how in the end we controlled this particular outbreak.

But why did it take so long and affect so many? When I arrived in Guinea early in the outbreak, I was saying cases that we couldn’t link to other patients. And I want to talk now about this question of listening and learning from those who live the problem.

In ebola, it means building fences that people can see through. In the past we used seven-foot high black plastic sheeting. People couldn’t see what was going on. They thought we were doing things like eating the dead—a good reason not to come for care.

It also means visiting patients’ household in an old blue pickup and spending two hours talking to their families. An old blue pickup because shiny white Land Cruisers meant you were an ebola home. Two hours because that’s what it takes in any sitting to convince someone to report a deadly quarantinable disease in those they love. And finally, listening and learning from those who live the problem means taking action.

As I said, when I arrived in Guinea, I was seeing patients who had no other contact with other known patients. A clear sign we were missing cases and we had lost track of the disease. Those of us on the ground knew very early on that a massive scale-up in response was needed.

It took time for those making decisions to hear us. Resources went into managing political risk rather than managing the disease. And in the months it took to hear us, the cost of the outbreak and of its control increased astronomically.

Ebola was one example. The other I’m going to speak about is something perhaps even more complex, gender-based violence. We do a lot to measure the problem now, a lot more, but we still invest very little in evaluating solutions. The area, and particularly in low-resource settings, and the area we have least evidence for, is how to help those already in the cycle of violence. We need not just to measure but to do, and learn from that doing in a range of settings.

A few years ago, we evaluated a health service for survivors of gender-based violence in Papua New Guinea, one of the highest-prevalence settings in the world for this particular problem.

The thousands of women and children who came to the service each year proved that if you provide free, accessible, high-quality care, many would come—something people didn’t think in the past. Almost all of those survivors that were coming to that clinic knew the person who was abusing them.

Many, particularly those affected by intimate partner violence, would stop coming to the service after one counseling session. They were telling us that they didn’t want help feeling better or accepting abuse in their situation, they wanted support to change it. The nurses who worked in that clinic were using their own salaries to give women things like bus fare to escape abuse.

So working with these staff who’d seen the problem and found their own solutions, we started a crisis support service. In the two years that that’s been operational, it’s seen over a thousand survivors, and it’s helped them access emergency accommodation, police, court, and other services. What we’ve learned in that time is that achieving safety and justice is possible, but it can take years and it requires interventions that link communities to effective services.

Building on this knowledge, we’re now starting a randomized controlled trial in Sri Lanka. Its testing low-cost solutions the community themselves have developed to address the problem of domestic violence.

Listening and learning from those who live a problem is essential to effective policy. It doesn’t cost more. It doesn’t waste time. It’s the best, most efficient way of identifying promising solutions to complex problems. And in the end it’s the only way we will know whether they work in the real world. Thank you.

Further Reference

How Ebola Roared Back, Kamalini Lokuge, New York Times