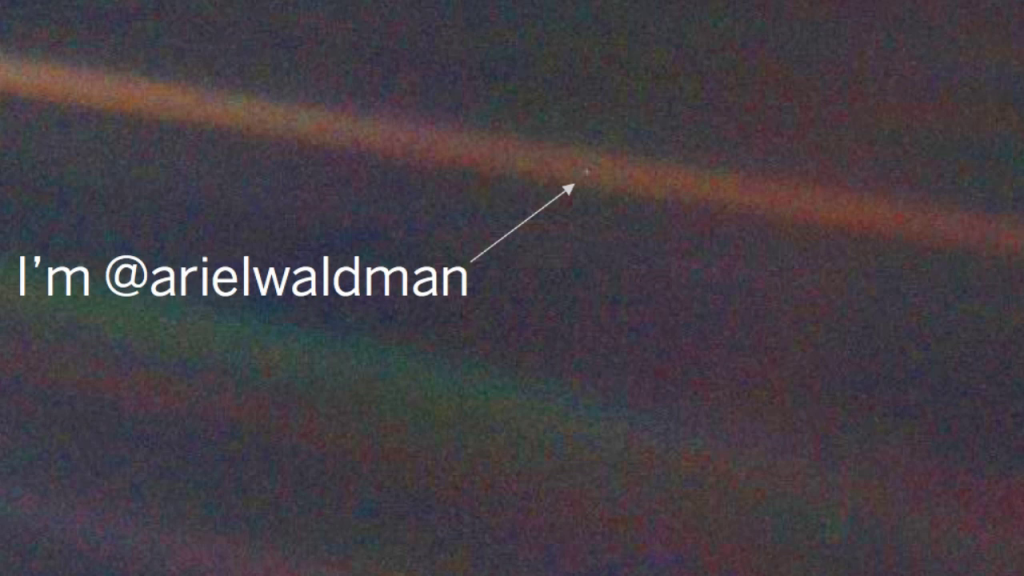

This is an image taken from one of my favorite spacecraft, the Voyager I spacecraft, that’s going to the outer reaches of our solar system and beyond. And if you can see that tiny little pale blue speck of a pixel there, that’s Earth as seen from about four billion miles away. So that’s where you can find me if you need me. But the reason why I really love images like these is because it really encapsulates how space exploration often changes our view of ourselves and our place in the universe. But similarly, I think we should change how we view space exploration.

As an example, how many of you are familiar with this image? Raise your hands. A good number of you. Great. Yeah, this is from Apollo 8.

And how many of you are familiar with this image? A few more of you. Okay. This is one of the well-known images from Hubble taken in 1995 of the Eagle Nebula.

And what both of these images have in common, obviously, is that a decent amount of us are fairly familiar with them. We’ve grown up seeing them in various places online and in schools. And we’ve kind of just seen them everywhere. But that’s kind of all we’ve ever done with them, is just see them. We haven’t really interacted with them, or tinkered with them very much.

And so when I talk about hacking space exploration, I’m really talking about hacking space observation. Because that’s really the relationship that most of us have with space exploration, is really just observing government agencies and astronauts exploring space on behalf of us. But we ourselves aren’t really exploring that much.

So, some of the history behind that. In 1969, we had a fairly historical event. We sent a man to the moon. But also in 1969, we sent the first message over ARPANET, the early form of the Internet. That message was “Lo” for login, and unfortunately the computer crashed shortly thereafter. But that said, with about forty years of hindsight, which one of these events has had a greater impact?

So, it’s 2011 and now the Internet has millions and millions, and actually close to two billion users. And yet with fifty years of space exploration behind us, only a little more than five hundred people have actually ever been in space. This to me is incredibly sad and broken. Because when you look at all those images from NASA that you’ve grown up with, while they’re breaking through sound barriers, they’re not really breaking through much else. They’re not really that open.

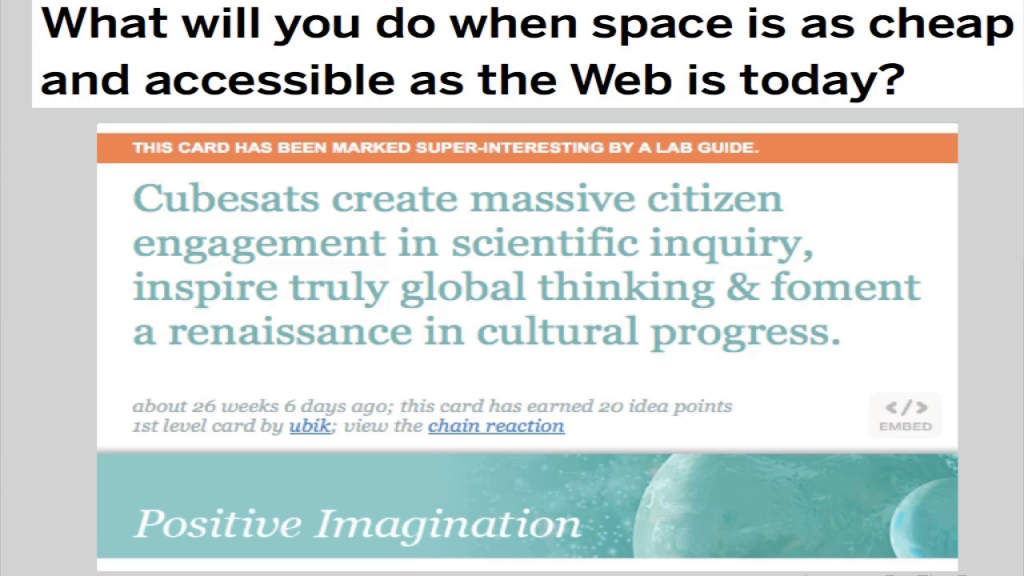

But what if space exploration were open? That’s a question that myself, the Institute for the Future, a great think tank here in Palo Alto, Jane McGonigal, a well-known game designer… We ask that to a number of people. We asked, “What will you do when space is as cheap and accessible as the web is today?” So if you can imagine owning a cube satellite for around the price of an iPod, how would that change us? We asked people to forecast how it might change us positively and negatively. And people talked about how it might change our environment, and how it might change our psychology.

But one of the most important things that I thought people forecast[ed] was that they thought it would create a citizen science renaissance. That simply having access to space exploration, similar like we do the Web, would actually inspire people to actively contribute to it and actually get involved in it. And this is because doing something changes how you see it. So actually doing science and doing space exploration, actively changes your relationship with it from something of observation to something you’re actively participating in and actively contributing to.

And this relates to my personal story. Because back in 2008, I was watching a great documentary that I recommend called When We Left Earth. It was a documentary about the Apollo missions and about NASA over the last few decades. And I found this so incredibly inspiring that I decided I wanted to work at NASA. But I had no idea if they needed someone like me. I have no formal science background whatsoever. My degree is in graphic design. I’d been working at VML, a WPP agency, for a number of years. And so I really didn’t know if they needed someone like me.

But I sent them a shot in the dark sort of email saying that I was a huge fan of everything that they did, and if they ever needed a volunteer or if they ever needed someone to work part-time or anything, I was around. It was little fangirl moment. And it was really interesting, because serendipitously, I was able to get a job based off of that email at NASA.

And it was this incredibly inspiring event. I got to learn from scientists about dark matter and robots and… Working at NASA is like getting paid to go to school. It was a really inspiring event. I got to learn so many things.

But one of the most important things I ended up learning while I was at NASA was that I didn’t need to be an astronaut in order to explore space. Not only did I end up learning I didn’t need to be an astronaut to explore space, but I ended up learning I didn’t even need to work at NASA to explore space.

And so I left. And this is something that a lot of people are realizing, is that like the Tron Guy who wants Tron to become a reality now, we want a space exploration to become a reality now. We don’t want to look like dorks for asking for space exploration. It shouldn’t be science fiction, it should be a reality. You shouldn’t have to be one of the lucky few who works at NASA.

But how can space exploration also goes one step beyond the sort of Instructables, DIY culture of doing something just for yourself. It’s about saying, “You know what? I have no idea how to build a robot, but I’ll be damned if I’m going to let that keep me from sending stuff into space.”

And this isn’t Photoshop, this is a real image. Kids from the UK actually built a system in which they can actually launch their teddy bears into space. So, these were eleven and thirteen year-old kids who who partnered with the University of Cambridge to do this, and they actually sent their teddy bears into space. they didn’t say you know, “Well, I don’t know how to build a robot, so I guess I can’t launch anything.” They didn’t really have any access barriers.

And so hacking science and space exploration isn’t just about getting excited and making things. But it’s about getting excited and making disruptively accessible things. Things that really disrupt the current state of science and a lot of the elitism around it, and truly make it accessible for everyone.

And there’s a lot projects that are already doing this. One of which is the Google Lunar XPRIZE which is a thirty million dollar competition to build and send the robot to the moon. And the really great thing about this is that it’s not government agencies who are doing this. This is teams of individuals from around the world who are doing this.

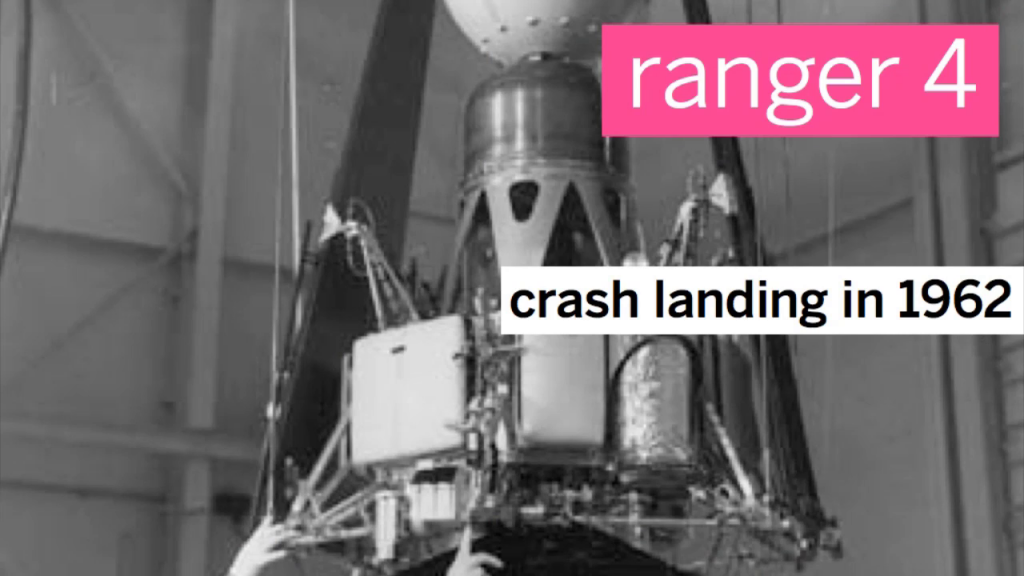

And it’s pretty exciting. Because if you can just imagine, just think for a moment, seven years before we landed a human on the moon, seven year time span, we were crash-landing robots there. So in seven years, we went from not even being able to successfully land a robot on the moon to landing humans there. As you can imagine within the next couple of years these teams from around the world will be launching their robots to the moon, it’s a pretty exciting decade for space exploration.

But if you think robots are kind of dumb, that’s okay. Robots are actually fairly dumb still. There’s a lot of things that humans are good at robots kind of suck at. And with that in mind is a project called Galaxy Zoo. And Galaxy Zoo is essentially an online interface in which people can go and classify, and potentially even discover, new galaxies that have never been discovered before. And Galaxy Zoo also solves an important data problem. Because as technology advances, we’re able to take in more and more data, which is great, but it becomes harder for people to go through it on a human level because robots still aren’t that great at it. But Galaxy Zoo solves this by having the sort of simplistic interface.

Galaxy Zoo essentially gives you an image of the galaxy, and it asks you some very basic questions about it like, is it a spiral galaxy? Is it elliptical? It asks you to classify it. It’s fairly low learning curve in order to a get involved in this, and it uses uses open data from the Sloan Digital Sky Survey and from Hubble.

But the important thing about Galaxy Zoo is that they don’t believe in using data monkeys. So this isn’t some sort of Mechanical Turk operation where you do work and some scientist takes the credit for it. The work you do on Galaxy Zoo actually gets credited to you. So, if you’re one of the people who discovers a new galaxy, your name goes on the scientific paper for it. So it’s pretty awesome.

And this actually happened in the case of the Green Peas galaxies. These were galaxies that were discovered entirely by Galaxy Zoo members and it’s because Galaxy Zoo not only gives you that pretty picture of an image, but it also allows you to dig into the data behind it. So if something looks a little bit peculiar or odd, you can begin to investigate it. And that’s actually what happened in the case of the Green Peas galaxies, and pretty soon after you had people on the forums, some with science backgrounds and some without science backgrounds, collaborating to try and figure out what these were. And they ended up finding one the most efficient star-forming galaxies discovered to date.

And if you’re feeling bad for the robots, don’t, because all of this human work leads to better machine learning. So hopefully the robots can get a little bit better at doing this without overtaking us. Hopefully.

So, if you’re intrigued about projects like these and ways in which you can actively contribute to space exploration, a lot of these products can be found on spacehack.org. And so you can find products like Planet Hunters, in which you can try and discovered new exoplanets that’ve never been discovered before. Projects like the University Rover Challenge, in which you can build the next wave of Mars movers. Projects like Citizen Sky, where you can investigate why a star gets eclipsed by a huge mysterious black object every so often. And projects like the TubeSat Kit, in which you can build and launch your own satellite for eight thousand dollars flat. So, all that’s on spacehack.org, which is a directory of ways to participate in space exploration that I created when I left NASA.

But all these projects follow sort of these different modes of invading space. They’re all about open collaboration and disruptive accessibility. So, really opening up the stage for people from all different kinds of backgrounds, not just developers, not just hardware hackers, not just designers, all different types of people, coming together to collaborate and really push space exploration forward. And they’re also about active contribution. So, these are projects not exactly like @-replying NASA on Twitter and hoping that they might listen to you. These are things that you’re actively contributing to scientific discovery through.

And one last point I want to spend a little bit of time on is the idea that open doesn’t mean accessible. And by “open doesn’t mean accessible” I mean that there’s a lot of data already out there and open in the scientific community. But it’s either buried deep in a government website, or it’s really difficult to understand. And so it’s not really that accessible. If you think back to the Galaxy Zoo project, that data was already open and out there. But it wasn’t until someone built an interface to it that it really allowed hundreds of thousands of users to go through and be classifying and discovering galaxies, which they are.

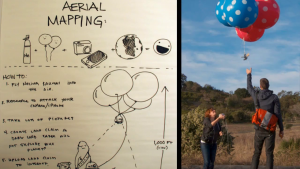

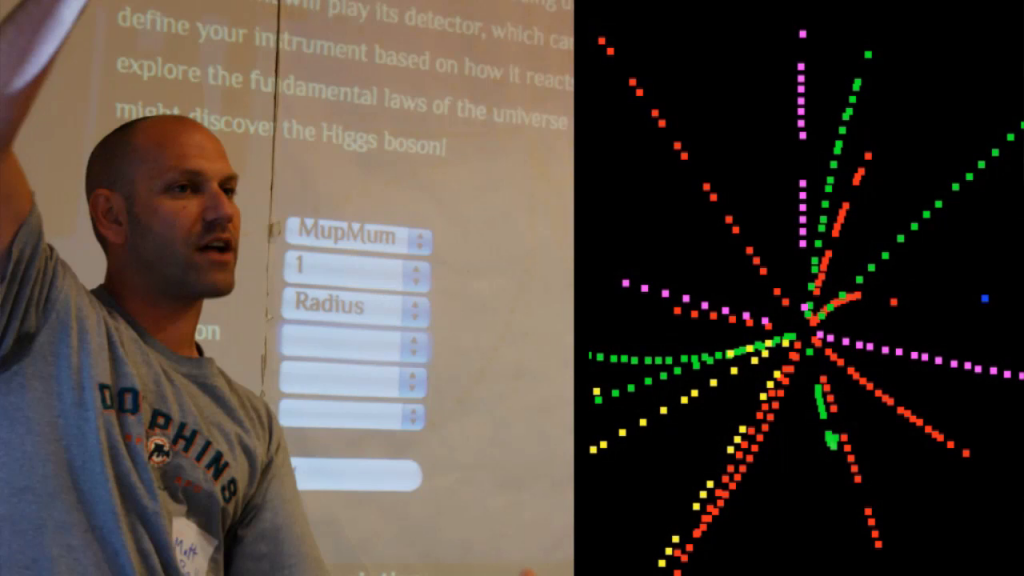

So out of this frustration that there’s a lot of open stuff out there but no one’s doing anything interesting with it came event called Science Hack Day. And Science Hack Day is essentially an event that brings together designers, developers, scientists, and just any enthusiastic person, in the same physical space to see what awesome, amazing things they can build with science over a 24-hour period. And people build some pretty amazing things.

They build high-altitude balloons that map the Earth’s surface below. We had someone build a lamp that would light up every time an asteroid flew by the Earth, so is sort of like a death lamp. We had people build DNA ties, so that it was a tie that would light up in your individual DNA sequence, depending on who wore it. The cool thing about this is that it was made by a couple of biotech students, and it uses Arduino, the microcontroller platform, to power up those light. But prior to coming to Science Hack Day, they had never used Arduino before. So it’s not just about people coming to learn about science, though you can definitely do that, but it’s about learning new ways of prototyping and really contributing to science and interacting with science.

We also had someone come and take particle collision data and map it to sounds. So if you could imagine instead of seeing a visualization of what a particle collision looks like, you could actually hear what a particle collision might sound like. It’s pretty amazing and, it was pretty amazing to listen to.

And right about now you might be asking, “Well, these are really cute and adorable and fun, but how are they actually contributing to science?” And the great thing about this particle wind chime is that it’s actually being looked into by accelerator laboratories as a sort of augmented diagnostic tool for people to be able to not only be surrounded by a bunch of screens telling them how the accelerator is doing, but also get used to the sounds and how it sounds and be able to tell if something sounds a little bit off about the accelerator.

So that’s really kind of the great thing about Science Hack Day, is it’s really meant to be a spark for future collaborations and future inspirations and future ways of contributing to science in unexpected ways.

So, since we’re in San Francisco, the next Science Hack Day is actually in November, and you all are invited to come. And I really hope and, with having all these designers and creative people here, that you all start thinking about unexpected ways in which you could contribute to science and space exploration. And I really hope that we all leave here, and it’s my dream that we all leave here, and get excited and make things with science, and really make amazing new ways of interacting with it and contributing to it.

Thank you.

Further Reference

“Galaxy Zoo Green Peas: Discovery of A Class of Compact Extremely Star-Forming Galaxies”, Carolin N. Cardamone, et al.

A post about this presentation at the PSFK blog.