I was sitting in the physics department tearoom, and I told an astrophysicist colleague that I’m thinking about public engagement because I’m going to talk about it at this year’s National Digital Forum.

“What’s that?” he says.

“It’s the annual get-together of the GLAM sector,” I reply.

“GLAM?” He looks puzzled, bemused

I realize this is what he’s thinking:

I send through my abstract for the conference describing how across the GLAM and the STEAM communities, we’re all talking about how we do public engagement better, asking if we’re talking to each other, and if we have any kind of shared language between our two sectors that make sense.

I get back this lovely email accepting my abstract, but just checking that I meant STEAM? Surely I mean steam? Maybe I meant STEM.

I’ve avoided using STEM for a reason. STEAM is a little bit like this. I know its cheesy. But STEAM is science, tech, engineering, the arts, and maths. And it does provide a place for me, a historian in a physics department, to feel like I might fit in somewhere.

So before I’d even got here, I’d answered one of my questions. Do we have any shared language that makes sense? Science thinks you lot are a bunch of glam rockers, and you folks might think of us as a lame plant diagram or a steampunk cosplay. So how about the public? They’re the ones we’re trying to engagement through a variety of means.

Public engagement describes the myriad of ways in which the activity and benefits of higher education and research can be shared with the public. Engagement is by definition a two-way process, involving interaction and listening, with the goal of generating mutual benefit.

National Co-ordinating Centre for Public Engagement, “What is public engagement?”

The British National Co-ordination Center for Public Engagement, which assists with and assesses UK universities’ public engagement activities defines public engagement thusly. And I’m really interested in the fact that it’s activities and benefits. It’s higher education and research. And that it’s defined as being a two-way process, with interaction, listening, and the goal of generating mutual benefit. Okay, so far so good.

So what does public engagement in universities in New Zealand actually look like? For a start, forget digital. We’re still thinking of public engagement as schools visits and guest speakers. Our institution see this type of public engagement like the marker Senatus Populusque Romanus. It’s just like a stamp. “We’ve done that.” It’s all done. Put it on your APR, which is your annual performance review.

There is little need to assess or measure, derive benefit, or reach out beyond the schools and public lectures model. So what I’ve been contemplating is the tension between space, place, and multiple publics.

I do not dream of Sussex downs

or quaint old England’s quaint old towns—

I think of what may yet be seen

in Johnsonville or Geraldine.

Denis Glover, “Home Thoughts” (1936)

Space. Where we meet the public matters. A public lecture delivered by a visiting academic in a university lecture theatre is very different to that same lecture being delivered in a genuine public space, be that virtual or actual. When Habermas said we call events and occasions public when they are open to all in contrast to exclusive or closed events, he wasn’t really thinking about the fact that a lecture theatre might feel public for those of us who are used to university campuses. But to negotiate a university campus, follow the arrows to a public talk, and figure out the arcane room nomenclature, all of these things are hard for people who aren’t used to university campuses. And I really wonder whether what we would call a public talk from inside a university is the same thing as somebody outside a university would call a public talk.

So, place. If we conduct our public engagement activities, these schools visits and public lectures, in Auckland, Wellington, Christchurch, Dunedin, are we genuinely reaching out to multiple publics? Confining our activities to centers that have a university again reinforces the sense that it’s people who have knowledge of universities that can access the engagement we’re trying to do. If we are to dream of what yet might be seen in Johnsonville and Geraldine, we need to be present in those places.

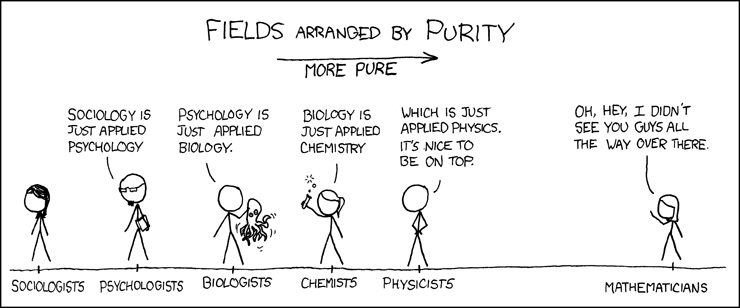

XKCD, “Purity”

Now, presence needs an understanding of multiple publics, and I have to thank Mike Dickinson for reminding me of this. I still recall the first time I used the phrase “multiple publics” in a Te Pūnaha Matatini strategy meeting. And I had a table of scientists, most of whom are physicists and mathematicians, look back at me sort of balefully and go, “Is that even a thing?”

And I explained when you’re sponsoring a lecture series and the events person who’s organizing it tells you that it’s really great to get your eminent science speaker in front of an arts festival because that’s a whole new audience, that’s not really multiple publics. University outreach or engagement tend to have two foci. We concentrate on school kids, who have to be there, right? And we also concentrate on already-engaged publics. So people who know about events and things that happen at universities. What I said to my colleagues at that meeting was we focus on people like us, or people like our students. And that’s actually just not good enough.

So, what does a new model of public engagement look like for science? I’ve got two images at play in my head. The first one is this:

Your local kindergarten or play center collage table, to which each kid brings their subjectivity. Their own choices, their culture, heritage, preferences, artifacts and [tāna/tānga?], and they make something new.

Now, a really good early childhood teacher doesn’t impose structure on the creative acts at that table. They wait. They leave space for the child to make their own meaning with the tools they have in front of them.

Now this is St. Heliers Church & Community Centre. It’s where my eleven year-old daughter has her piano lessons on Wednesdays. When I go there to pick her up, there are always at least seven things going on in that building. Piano lessons, after-school care, children’s choir, dance classes, senior exercise classes, a meeting or two. There’ll be an MP or local board member talking to constituents. And there’s always a table with free excess produce from someone’s garden. There is a tangible sense that this is a public space, teeming with multiple publics using it for the our own purposes.

So what I’m kind of thinking about is that a public space, be that virtual or actual, must be a place that provides both the collage table, quiet space in which people can create meaning, and the community center. Dynamic space filled with meaning makers from multiple publics. As universities struggle to think more deeply about public engagement, we need to learn from you who inhabit spaces that bridge this quietude and this dynamism. So please come and talk to me about it.