Ethan Zuckerman: Most of our Forbidden Research conversation so far has been in the realm of the scientific and the technical. But those aren’t always the areas in which research finds itself off limits, somehow difficult to talk about. We’re now going to switch gears quite sharply and move on to a topic where to the extent that research ends up being forbidden, it’s really for cultural reasons. And it’s really people’s in many cases inability to accept the idea that Islam, a religion practiced by more than a billion people worldwide, can be compatible and completely consonant with issues of human rights and women’s rights.

So we have two speakers who are going to talk about this topic in a session that we’re calling “Rites and Rights.” We’re incredibly lucky to have with us Alaa Murabit, a physician and activist, a UN advocate for the sustainable development goals, from Libya. We’re also very very happy to have with us Saeed Khan, who teaches Middle Eastern studies at Wayne State University, researches extensively on Islam and the diaspora, and the politics of the Islamic diaspora in the US and the UK. So let me welcome them both to the stage for Rights and Rites.

Alaa Murabit: That round of applause was both for Missing Pieces, but more for me. Because I narrated it.

We’ve been having this conversation about technology and about forbidden research within the sciences. And while they may not seem very connected, I would argue that they actually are. If we look at a lot of the things we’ve been speaking about today, be it genetic engineering or the things that occur in our daily lives, the challenge of reproductive rights, or global peace and security, a lot of the stagnation, a lot of the challenges, are actually rooted either in the perception of religion or in the political manipulation of religion. People utilize it for their own political and economic advantages every day. And regardless of how much we research, we find that actually putting it into practice and policy becomes quite difficult because we have to deal with one another.

I’m joined by Saeed Khan who is a professor at Wayne State University and has actually done quite a bit of work on Islam and the challenges of modernity. And today we’ll be taking the conversation through about four key points. We’ll be talking about the perception of Islam or Muslim women here in the United States, and then moreso globally throughout the Global North.

We’ll then be talking about why the political climate and security climate are actually quite different than the realities on the ground, and how that translates. And we’ll be referencing specifically current policies on countering violent extremism, because that is such a hot topic both in the Global North and the South.

And finally we’ll be finishing off on what are the key next steps in this dialogue? Is it research? Is it policy? What needs to be done to actually change the situation for the 1.7 billion Muslims and for everybody else?

So I’m going to start by asking you, given the work that you’ve done and the research you’ve done on Islam, what are the perceptions here in the US?

Saeed Khan: Uh…well, not great, I think it’s fairly safe to say. But there is a recent Brookings Institution survey that was done last week, as a matter of fact, which showed that things are slightly improving vis-à-vis the perception of Muslims, maybe not so Islam per se. And it’s interesting to see that this report came out after the tragedy of Orlando. That despite that, there seems to be now the turning of a proverbial corner in how people perceive Muslims. And part of that perhaps is an intensified civic and political engagement by Muslims, particularly those living in America, more broadly North America.

But when I take a look at Islam within the Western context, I actually invert the methodology. I’m more interested in seeing how our Western society’s mutating instead of looking at the mutation of Islam per se. In the United States, we are living through quite a bit of a paradigm shift when it comes to the demographics of the country, particularly as we’re lurching toward 2043, when by most estimates the United States is going to become a majority minority country.

Because taking a look at this phenomenon that is sometimes and colloquially called Islamophobia, I noticed that the perception of Muslims by broader society was eroding the farther one moved away from 9/11. And this seemed to be at least initially counterintuitive, that if there were ever a time when people would have the most negative perception of Muslims, it would be right after the terrorist attacks in 2001.

But there was a slide that persisted throughout the aughts and into the 2010s. And especially culminating around 2010, some of you of course remember the controversy of the so-called “Ground Zero Mosque,” as well as Reverend Terry Jones (not the Monty Python Terry Jones) wanting to come to Dearborn, Michigan and burn Qurans. And this was also coincident with the August 2010 Time magazine cover story “Is America Islamophobic?”

And so I started to take a look at various markers in order to test the hypothesis of in fact, what’s the relationship of Islamophobia with then the changes that are happening to the United States? 2010, the US census comes out and shows that for the first time in American history the number of non-Hispanic white births is being outpaced by non-white births. Fast forward to 2013, and the Pew Center for the study of religious life in America coming out with a survey showing the religious demographics. For the first time in American history it’s a country that is no longer majority Protestant. So we find then that the White Anglo-Saxon Protestant essentialism of American identity was now becoming less white and more brown, less Anglo-Saxon and more Latin American, less Protestant and more Catholic.

And I was trying to situate Islamophobia within this. And for a group which depending on the survey is either 0.6% of the population or 3% of the population, this is a group that is invariably lacking in social and political capital, which makes it a fairly easy target.

Murabit: So I’m going to play devil’s advocate a little bit and say, regardless of Islamophobia in America, I could argue that there seems to be a perception, even from people who may not necessarily be Islamophobic, that Islam does not exist with women’s rights. That the two are mutually exclusive.

Khan: Right.

Murabit: Now, that’s something that’s been very apparent based on almost every research conversation that’s been had. That there’s a moral obligation for the US to promote women’s rights and by default then, minimize the role that Islam can have politically. What are your thoughts on that?

Khan: Well, in the United States in particular, we find then that the Muslim woman becomes the site of contestation. And we see how she is instrumentalized both domestically as well as in a foreign capacity. That somehow or the other she needs to be saved. She needs to be saved from her own religion. She needs to be saved from our own culture. She needs to be saved from her own patriarchal ontology.

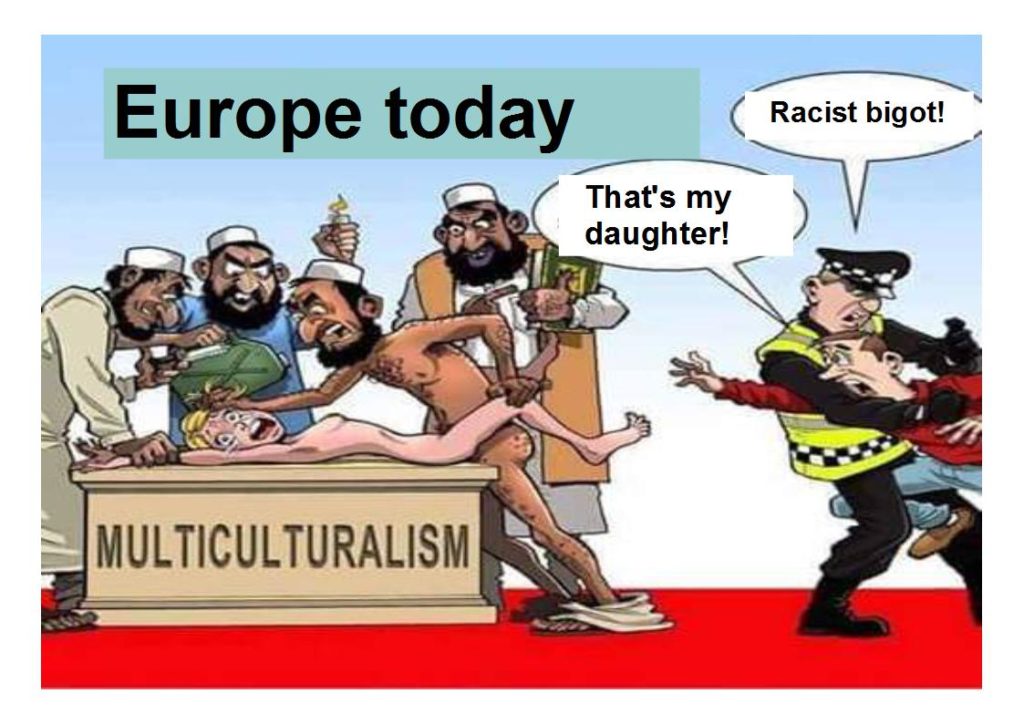

And as a result of this, you find then that the manifest destiny of salvation, of emancipation, becomes such a strong trope. And it’s fascinating in the European context where there’s also a moral panic occurring, that the magnum opus of post-Enlightenment philosophy, the European Union, everyone getting along, seems to now be structurally and systemically flawed.

And as you see with this graphic here, you find of that here are some Muslim men, ostensibly clerics or at least pious, who are raping multiculturalism. And it’s also fascinating to see that it’s not just the Muslim woman who’s being instrumentalized here but it is also Europe that perceives itself as being a woman being raped or having her consent taken away from her.

Murabit: Well, I tie this a lot into the work that I’ve done on sexual violence and conflict, because we often discuss how women’s bodies are seen as the borders of a nation. And so while many people argue with Islam and honor killings, that Muslim society see Muslim women as the honor of that family or that community. But what strikes me is that’s actually quite similar, when we talk about Europe. Despite the fact that it is not a Muslim country, women are definitely seen as the honor of the community. And that’s why we saw the political outrage following the attacks in Germany.

So, I think where I would like to veer this to, then, is from a more global perspective— If we’re now looking okay, so there is this assumption that women are objectified and oppressed, need to be emancipated, as you said, that Muslim women do not have agency or capacity. Then why are we asking Muslim women in particular to be our our tools for first information in countering violent extremism? Why now are we emphasizing the role of Muslim women in global security? Why now, if we have argued for so long and we have spoken for so long about the need to liberate them, be it in Iraq and Afghanistan, wars have have been started based on this assumed morality to protect Muslim women? Why now are we saying okay, so they are key in this fight?

Khan: Well, I think it’s the understanding sociologically of not only their visibility in the public sphere, especially when we see the debates happening in Europe, but also the centrality of Muslim women when it comes to the nuclear family. And so we find that as a keystone or as a linchpin, to go ahead and place this focus and to usurp the narrative of them, essentially to take the agency not just away from them but from the Muslim community, becomes then a very easy and exploitable measure.

Now, in the case of Europe, about a decade ago, at the time president Nicolas Sarkozy when it came to the hijab ban was speaking on behalf of Muslim women. He was saying the reason or the impetus for this ban is to liberate Muslim women ostensibly from themselves. And what was ironic about this is that Sarkozy saw himself as a walī, which is a term in Arabic which means guardian or custodian. And it’s particularly reminiscent to the older sociology of Islam, of tribal society. Now, that society was predicated on three major factors: being patriarchal, being tribal, and being custodial.

So as society has moved on, and particularly Europe with Rousseau’s social contract and most of our interactions being contractual, here was Sarkozy being a throwback to a bygone time in Islam which actually Islam has evolved from. From custodial societies to contractual societies. And he felt the need to now be the tribal chieftain for French Muslim women despite the fact that of course they haven’t asked him to do so.

Murabit: So then how do we marry that, the sense that in the Global North we’ve decided to dictate and say what can be worn, what can’t be worn, what they are capable of, that they need to be protected, etc., with the fact that we politically sit down at tables with the countries which most export and support the negation of women’s rights under the name and under the guise of Islam?

Khan: Well, I think part of it is we have to deconstruct this fallacy of morality being the prime driver of foreign policy. I would say that it’s not—and of course people are free to debate this that it’s immoral—but just for the sake of symmetry I’d like to keep morality and immorality out of the equation and say that at best it’s really an amoral relationship.

And it’s remarkable how, then, the narratives form in the liminal spaces. I think earlier we were talking about how the liminality between a woman’s legs then becomes both how Muslim women are perceived and certainly how Western women are also, with the securitization of the West, need to be protected from this menacing threat that is coming out.

So when we take a look at how, then, an amoral trope is employed, how to reconcile dealing with governments, how to deal with societies that are oppressive, it comes down to the dollars or it comes down to the euros. And it’s fascinating to see these contradictions without any sense of guile, without any sense of self-reflection. And I’ll give you one example, again going to France. And by the way if anyone’s French, I apologize. I’m not trying to be bash French. I love flying Air France, by the way. So hopefully that’ll serve me as cover.

Now, this is interesting. This is actually a Belgian a woman, and these are the catwalks of Paris. It’s perfectly okay to feel as though you’re championing Muslim women and trying to liberate [them] from the “fortress” of their physical countenance being oppressed behind a burqa and the niqab, unless you can profit from it. So whether you are Girbaud or whether you are Dolce & Gabbana, and you are able to then make it part of haute couture, then it’s perfectly acceptable.

In Paris today, a woman wearing the hijab going to Tati, which is a downmarket discount clothing store, spending twenty euros is seen as an existential threat to French values and identity. But, a woman in a full burqa, from Qatar, who’s on the Champs-Élysées at Hermès burning through two hundred thousand euros is welcomed with open arms. So you see it has something to do with economics being if you will the new morality and the new marker by which these relationships are negotiated and contested.

Murabit: But I’d argue that it’s always been the morality. That’s how potent religion became politicized in the first place, was because people realized it would make some money.

Khan: Well, there’s a difference between I think the politicization of religion and the commodification of religion.

Murabit: Fair enough.

Khan: And so I think what we’re finding here now is that everything’s for sale.

Murabit: Fair enough. I’ll agree with that, but I do think that the two go hand in hand.

Khan: Absolutely.

Murabit: So, in Libya a lot of our work has actually revolved around utilizing religion and utilizing scripture and the sayings of the prophet (hadiths) to actually be able to change the conversation. Because while religion may not be the cause of violence, the manipulation of religion is definitely what fires people up or what excuses violence.

And so a lot of our work has revolved around working with imams, so religious scholars and leaders, to actually talk about the underlying origins of where this conversation started. Because when Islam was first brought into our societies, the reason it was in partly embraced was actually because it was seen as liberating women. It was seen as putting them in a better position than they had been in in pre-Islamic times. It had been seen as affording them more rights, affording them more access, affording them more opportunity.

So we wanted to see where that deviated. And it became very very clear in much of the work that we did that there was a great political change in the 1970s and 80s in particular, in my region, in the North African region, that had a lot to do with the exportation of ideals from Saudi Arabia, and the exportation of a particular methodology of Islam from Saudi Arabia. And that was able to reach other countries, because of globalization. Because now we had their radios. Now our scholars went to Saudi Arabia to get education and came back. When the age of satellite came, we got to see, for twelve hours a day, Saudi Arabian scholars speak about the right way a woman should dress, the right way a woman should look, and how important it was to keep women out political and public life to ensure the integrity of the family unit. Because if she is too busy running a country she cannot run a home.

So it became exceptionally important for us to actually attack this head-on. And I still remember one of our meetings in Libya when we were speaking about transitional justice, because sexual violence in conflict had been a great issue. And we were sitting across from the United Nations political mission. And we had quite a few young men who were part of our local transitional justice teams.

And so the UN mission asked the Libyans, “Well, where are your women?” Because out of about thirty people I was the only woman in the room. And they looked back at the UN team and said, “Well, where are yours?” Because the UN team didn’t have a single woman with them.

So it became very interesting to me that we often cite women’s rights as a cause for us to become involved, for us to stand upon. Be it sexual violence in the UK’s initiative there, or Iraq, Afghanistan, and how often we cite Iran as being a limiter of women’s rights. But at the same time, we don’t ever hold to account countries which have fully supported this. And I know you and I had been speaking earlier about the specific relationship that the West has with Saudi Arabia. And given this newfounded or newly rejuvenated relationship with Iran, how that might change.

Khan: Well, there’s a couple of different elements to that, Alaa. I mean, first of all let’s remember back at the 1995 Conference on Women in Beijing, and some very well-intended Western delegations came into the conference asserting the need for greater choice for women when it came to their reproductive healthcare. And particularly this was an issue dealing with how to have access to medical procedures.

Well, it kind of backfired in a place like India, where people started to use the ultrasound in order to then determine the gender of the fetus and then have selective abortions based on that gender. Which created an epidemiological if not a demographic a crisis in some provinces like Rajasthan.

At the same time, it’s also important to take a look at when it comes to the Orientalism by which we tend to look at not just women in these countries but entire regimes and governments. It’s always a matter then of seeing how we can exploit it, what can we sell.

Now, case in point in Saudi Arabia, of course there’s this distraction about an anthropological anomaly. The fact that Saudi women are not permitted to drive. And this becomes then the litmus test or the barometer of an entire society, irrespective of understanding, again, the underlying sociological and anthropological cultures. We’re looking at a population of thirty-five million people. But the reason I use the number thirty-five is that at the same time, not only do we correspond and interact with this country at the highest levels, we also sell them thirty-five billion dollars in weapons.

So the idea, then, that we have a willing market—

Murabit: Which then usually end up in the hands of extremist organizations that we then combat with billions of dollars, twenty years later.

Khan: Whether we turn a blind eye or not to this is I think still an open question that’s being debated. But it’s kind of interesting to see that a year on from signing a deal which ostensibly removes nuclear weapons from the region, we also then highly intensify our sale of conventional weapons to go ahead and deal with a phantom menace that we had purported to go ahead and reduce.

Murabit: And then we’ll be fighting again in twenty years.

Khan: Boy, I mean, you’re waiting that long?

Murabit: So I will open the floor to questions in a moment, but before that I do actually hopefully want to leave you on a bit more of a positive note. Because I would like to think that there is a silver lining. And that is that I always say the future of the Islamic faith, in my opinion, is inarguably and very fearlessly female.

And I say that because in the past ten to fifteen years [I] have seen a complete I want to say revolution of thought about the interpretation of Islam led by women. And civil society has really kind of taken a leading role in a lot of the developing countries and in a lot of the post-conflict and transitional countries in the Middle East and North Africa and Asia Pacific, where we see them saying okay, so this can no longer be what the blueprint for our society is, or for our culture is.

And there seems to be an interest to separate culture, which is a very very strong proponent of a lot of the more traditional and archaic features, from religion, and from the interpretation of religion. And for me this is key because for the past 1,600 years, the interpretation has been very solidly male. And it’s been elite male. It’s men who have authority and have power, and have the ability to create more authority and power based on what they say they find in the word of God. And you’d be amazed at how hard God is to debate with when somebody says that they’re sure that’s what he said.

So for women in particular, it’s been an uphill battle because the second you begin to debate a lot of what has been interpreted, your honor comes into question, your integrity comes into question, your sheer humanity comes into question from a lot of people, some very well-intentioned, who simply practice the faith but feel as though you are going against the word of God.

So I think what I would like to open up questions on is really first, recognizing what we do have and we inarguably have, and we’ve spoken about it a lot, the traditionalists within the faith who dislike this current trend of more open interpretation or at least more inclusive interpretation. But also how we’re going to marry the political and the economic, which we’ve emphasized tend to be driving a lot of the decisions made in our regions and globally, with the moral, and with the religious, and with the social. And with the cultural, which will take much much much longer.

Khan: Oh, absolutely. I mean, I think it’s important to recognize that Islam, when we’re looking at states of matter, and this is something I always challenge my students on, asking them which state of matter it is. And usually you can figure out where they are on the religious spectrum with the answer that they give. And I know there’s four states of matter. I’m here at MIT. I know about the plasma, okay. I took some NatSci courses as well.

But the so-called traditionalists will say, “Oh, it’s a solid.” Some who are perhaps a little bit more ascetic in their outlook will say it’s a gas. And I say no, it’s actually a liquid, because it takes on the volume or the dimensions of the vessel in which it finds itself. And that vessel of course is the culture. And so that’s why you have all this cultural diversity.

But the point that you made earlier is so critical, of in 1979 with the exportation of a very essentialized cultural paradigm from Saudi Arabia. This then ruptured the organic cultural evolution and marriage of religion in so many different parts of the world. And part of the reason that that happened is that these societies started to develop insecurities that their Islam was not authentic. Many of these places were very syncretic when it came to their Islam because of how heterogeneous their societies were. South Asia with Hindus, Sikhs, Buddhists, etc.,

Murabit: They couldn’t read the Quran themselves. They couldn’t speak Arabic…

Khan: They didn’t have Arabic as their lingua franca, so they became highly dependent, then, on the search for authenticity. And of course the Saudis were only too happy to do so with the kind of authority that they were trying to assert.

The rest of the Muslim world, especially South and Southeast Asia and to a certain degree Sub-Saharan Africa, developed a kind of theocultural penis envy, in the sense that they said, “Well, we don’t really know, so we will defer to you.” And so you notice it is from that point where things start to start to tip.

Regarding how women’s agency needs to then be deployed, it has to be both on the theologically interpretive as well as the sociologically interpretive. So in a sense what they need to do is have an intervention of Foucault and the fatwa. They have to understand how social control has really then been such a major part of the equation when it comes to who holds the levers of power, the exclusive levers of power, when it comes to this interpretation.

And you’re finding Muslim women now are not only pushing back and challenging that authoritative structure but doing so in a much more sophisticated way. Some of you are probably aware of—

Murabit: As you would expect, of course. [laughs]

Khan: … Point taken. Now where was I? Some of you are probably familiar with the fatwa that was just released a couple days [ago] from Saudi Arabia saying that Pokémon Go is a sin. Okay. Now, most people have dismissed this off because they see it as being just another embarrassment for Muslims to have to now answer to. Wow, they’re even taking the fun out of holding up your phone and walking into walls and all the other things that Pokémon Go does.

But the fact that the fatwas or the advisory opinions that Muslim women are seeking are much more refined than these kinds of fatwas which are obviously the product of consultation— Somebody had asked the question of a cleric to say, “Can I play Pokémon Go and not go to Hell?” Muslim women aren’t dealing with things that are that argot.

Murabit: No, that’s very true. And I actually want to point out some of the work that we’ve done in Libya and really kind of looking at both the social and political, and religious, involvement of women as I think being the single greatest game-changer. Not only for Islam but I think for every faith. I think when every faith becomes more inclusive it tends to change from being an organized religion meant to control and oppress and gain power, and becoming more of a faith where you can actually feel as though you have a connection.

In Libya we were able to start a campaign called the Noor Campaign. And it’s actually now been replicated globally and has been cited in the United Nations Security Council Global Study on Women, Peace and Security. Because within six months, by working with the religious institutions and getting a lot of— As I’m sure many of you know, women’s rights organizations do not have a lot of innate credibility. So we ended up having to borrow some from a lot of the religious institutions. And we worked very very closely with them as well as with social and political thought leaders within our communities, and some tribal elders, and a lot of the more traditional leaders.

And we went through schools, universities, mosques, etc. on the ground, and within six months were able to reach over 2.2 million people indirectly. And that’s in a country of six million. And over 57,000 directly, having them complete surveys on where they think the root of this problem is. What is the root of violence in our community? And a lot of people will cite answers that are I think often left out of our conversations. So some will definitely say, “Well, you know what, it’s my religious duty.” But the vast majority will say, “Well you know, my grandfather was attacked.” Or, “The land that I don’t own any more is because they came and they took it from me.” Or look at what they’re doing to our neighbors or our cousins in Country X or Country Y.

And by doing this, by being able to actually fully marry this concept of religion as an excuse for violence, and manipulated religion actually as a cause to promote violence, with current geopolitical realities and security realities, we were able to have a more honest conversation about what was happening. And from there create actual strategies which combated extremism. So being able to say okay, so if the problem is that you don’t have a job and they’re providing you money and that’s why we’ve joined, then why don’t we talk about providing you a job in your local area. Rather than saying well, religion is clearly the problem so we have to close down all the mosques. Because by closing down those community centers, we actually have more people staying at home sitting on the Internet and finding what do we call it, the deep web? Finding all those kind of different interpretations of Islam which have actually lead for us to be in this situation now.

So I’ll open up the floor to any questions anyone may have. Do we have any? Easy questions only, obviously. I have a rule.

Audience 1: I have a comment, honestly, more than it’s a question. And maybe this is the first time I’m speaking about this in public, but as someone who’s from the Middle East, I’m all the time very much surprised that we all the time, even when we discuss that in the West, we manage to look at things as we have to be a tribe. One of my major problems with countries like Saudi Arabia or even the moderate Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan [is] that they have a state religion and then there are all the laws and all the things that have to apply to my life have to be coming from that religion. And even today I mean, I was was a woman who wore a hijab when I was thirty, and I stopped wearing a hijab four years ago. And I would even wear the proper full hijab with all of the things.

And one of the things I noticed when I stopped wearing that hijab [was] that I stopped being that “cool Muslim.” Because why do you care if a woman is wearing a hijab or not wearing a hijab? That’s my problem with the whole conversation that is going on all the time in the Western countries, about we do all the time have to prove, as a woman, who is Muslim and wearing a hijab. You know what, I’m moderate. I’m amazing. I can do cool things. And now, with not wearing the hijab or just being like a woman who could be anyone, I’m all the time not getting the same kind of status that I used to have before.

I’m also thinking when we’re all the time trying to discuss the topic of Islam and women, we all the this time go back to the point zero of having us all as one block. My dad’s name is Mohammed, and I travel to Yemen and Egypt, and then I would be going into security checks all the time in London and Paris boarding to America. And in the countries where I come from, they look to me like, “You know, you’re secular. You don’t want to…” It’s just like you’re all the time stuck in the middle, and I feel like… I mean, I’m just raising this idea of we all the time have to touch on the topic as [if] we were all one block, we all were born from Muslim families, and we’d still be the same. And then how I look and what I’m wearing will just affect a lot how people will have stereotypes about my life. And I just kind of find this very— We’re in 2016 and we still need to say, “Oh you know, there are cool women Muslims that wear hijab but they can still be doing amazing things.”

And then the American— Yeah, there are, but there are other women who are also from that region and not necessarily that person, and basically does not want to be ruled or associated with a state that has a religion. There are a growing secular— I have a lot of friends in Tunisia, which I think is the most progressive Arab country, who basically, not wearing a hijab, and they drink alcohol, and they still fast. And they sometimes play. And they have some rules that they follow in their lives.

I don’t want to like— I don’t want to go so long. Okay, that’s the last thing I want to say. The last thing I want to say is just like, because we’re trying here to talk about “forbidden research” and forbidden questions is, why do we all the time have to be looked at as one block with all the same characteristics and category? That’s it. Thank you.

Khan: Thank you. Well, I think your point is extremely salient and exactly why for forbidden research is the metanarrative here. It’s in order to unpack a lot of these monoliths that have been created, a lot of these very reductive tropes that are then ascribed to say well, there’s only two kinds of Muslim women. There’s the either or the or. And the need to then move beyond that.

But the point that you made regarding state religion, if you’ll allow me. The United Kingdom has a state religion, as well. So I don’t think it’s a phenomenon that is just limited to the Muslim world. There is a state religion. It’s about how civil society negotiates and navigates with that state religion, and what is the process of political and civic participation, and then creating some kind of a society around that. So I’m not sure how much the state religion, by itself, then becomes a restrictive measure.

[inaudible comments from Audience 1]

Murabit: I would add, though, in terms of how you were talking about this reduction between being one type of Muslim woman or the fact that we’re all looked at very homogeneously, that’s not isolated only to Muslim women. That’s actually something that the female gender suffers with, or female sex suffers with entirely. And if we look at that from a women, peace, and security perspective, when we talk about women’s inclusion in peace and security globally, regardless of whether it’s a Muslim country or not, they are often looked at [as] victims and solely victims, and now only recently some people look at them as victims and perpetrators, right?

If we talk about it in a social, you are either a prude or a whore. You’re either a…in cultural terms what was it? Kim Kardashian or an Ayesha Curry. You are one of always two, right? So that’s not something that’s limited only to Muslim women. That’s a reduction that exists within the entire sex. And it’s the way that unfortunately unless women take stronger roles, in my opinion, in politics, public life, and security in particular, that will continue to stay, so.

Khan: Well, isn’t the point that John Irving made in The World According to Garp— He said that in this crazy mixed-up world, a woman is either somebody’s wife or somebody’s whore, or fast becoming one of the other.

Murabit: Well, that’s a fair way of saying.

Please say your name.

Michael Sigurski[sp?]: I’m Michael S. In regards to Muslim countries, governments, cultures, that use a particular interpretation of Islam to subjugate women, do you know of any examples or methods to change that? And in a broader sense, do non-Muslim countries have any place to try and change the interpretation of Islam, or does that kind of change have to come from Muslims?

Murabit: So I’ll give you a specific example, actually, of some of the work that women are doing in this space. In Morocco four years ago now, there was a young woman who was raped and was then forced to marry her rapist. And it was under the existing law, based on interpretation which said that if you are raped the man has a choice: he can either suffer the consequences or he can rape his victim. And it was actually a group of women Islamic scholars and civil society activists who said, “Wait a second. If your excuse for this law is religious, then we’re going to find how your interpretation is not in line with the faith.” And it took them about a year but they were actually able to completely overrule that law for everybody following.

In Algeria, you have the [?], which is about 3,000 women who now are really the social and moral compass for their local communities. They’re the ones who go into the community, they’re the ones who actually help to deal with a lot of the more “traditional” resolutions to conflict. So rather than going to an official court, you’ll go through that system. So they do exist. They are still on a much smaller scale and that’s a lot in part because of the political systems which are exercised a lot of Muslim majority countries, where it is very centralized power, very controlled, very muscular type of authority. But they do exist.

Do I think that anybody else has the right to reinterpret Islamic legal structures and systems other than Muslims? I definitely think all voices need to be heard and it needs to be inclusive, but I don’t think it’s sustainable unless it’s indigenous. I think being realistic, if we’re talking about culture, culture is something that people genuinely need to believe needs to change, and want to change it within their own society, right. And and I think if anything is imposed, it follows a historical tradition of things being imposed in a region and automatically becomes discredited, becomes unsustainable, and becomes opposed, just by nature. And it could be something wonderful. It can be vaccines, and people can be suspicious because of the history that imposition has had, right.

So I do think it has to be indigenous, and I think people within the region have to genuinely start saying okay, so what interpretations of faith? Because Islamic law…it changes. It’s based on your own interpretation, or on the interpretation. So what interpretations of faith are influencing our laws? Who are they benefiting? And how do we alter them to benefit the global community?

Khan: I mean, I think the historical colonial record unfortunately provided quite a bit of a taint to the organic development of law and jurisprudence in many Muslim countries with the removal of Sharia and then the imposition of European legal codes. And it’s important to understand that these legal codes come with their own historical, cultural, economic, and political background which is inorganic to the countries in which they are then being imposed. And a lot of what we find now is a kind of walking back to find a system restore point in time where things were pristine. And unfortunately going back three hundred years with a society that has already moved three hundred years beyond and is moving incrementally faster from that point makes it a Herculean challenge.

Murabit: Next question?

Natalie Gyenes: Hi there. My name is Natalie Gyenes and I work here at the Center for Civic Media. And I’m wondering if, similar to for example Christianity where there is a central voice with whom especially in diaspora communities you can esteem them with high regard, and as religion progresses they can have greater influence over the general population within and outside of a particular religion. In Islam, does that voice exist? Who can it be? And who should it be in the future, especially with increasing women’s rights and the voice of women coming to sort of the forefront of religious interpretation?

Khan: I’ll take it?

Murabit: You can go ahead. I’ll [inaudible].

Khan: Sure. The easy answer is it depends. There’s actually certain schools within Islam that have a central figure. So if one were to take the analogy of Christianity, there is a Catholic side to Islam. The Aga Khan, for example, who is the figurehead and authority for the Ismāʿīli community is such an individual. Within the broader Shi’i community, you have what are known as the marjas, the highest ranking clerical authorities. And people whether they are in Tehran or Dearborn will go ahead and follow the proclamations and interpretations of the authority. Within the Sunni constellation, it is a much more decentralized clerical authority.

And it’s always fascinating that when I have discussions within an interfaith capacity, some of the most ardent advocates who are seeking a single voice for the Muslim world are themselves Protestant Christians. And I’ve never really understood that because they’re much more acclimated to the idea of decentralized clerical authority. But I can appreciate why they’re seeking that monolithic voice. Unfortunately what it does is it flattens the landscape. And it doesn’t then take into account the cultural nuances which have to be understood in one way or the other.

And to take a look at Islamic jurisprudence, particularly among Sunnis, the four major schools of law which developed, at least two of them developed because of geographic considerations. The Hanafi school, for example, is a very decentralized school which defers to jurists within a particular locale, and I’ll give like one example.

To go ahead and use the jurisprudence over water access of Medina is going to be different from the water access laws that affect Baghdad, because one is in a desert and one is in a very fecund area. Another which was a consequence and a reaction to that said, “Well, now you’re getting to be too diffuse when it comes to your laws, so let’s go ahead and focus on Medina because this was the Prophet’s city.” So you have to understand that these legal systems work as dialectics to one another. That’s all been in place. It’s more of a matter of who’s holding the levers and who’s trying to assert one of these schools over the others as a form of power.

Murabit: And in today’s political reality that’s unfortunately what’s happening. So in a lot of Muslim majority countries where the religion is part of the state, you actually do have a central figure who is ordained by the political leader. So religion and politics tend to get muddled very quickly, and people are being told things in the name of religion that actually benefit the political authorities. And the best example of that is Saudi Arabia, where they made a clear negotiation with the religious leaders to be able to afford them their own individual power to be able to maintain their political power. And that’s something that unfortunately has shaped, I would argue, Middle East and North Africa in particular, Sub-Saharan Africa, and Asia Pacific as well.

Khan: And I think there’s also this implicit imputation of religious authority which is then conferred upon leaders. And I think the place to watch right now is of course Turkey, and to see the way that people regard Recep Tayyip Erdoğan. Here is a civilian politician, but there are people who regard him as almost being a neo-Ottoman sultan. And if you recall, in the Ottoman Empire after 1517, the sultan was also the calif.

Murabit: So I think we have two questions. We’ll take— Oh sorry, three questions. So we’ll take all three at once, and then we can answer because we have to wrap up soon.

Bennett[?] Krauss Hi, I’m B. Krauss. Something that really resonated with what you said during the panel was how women’s bodies are seen as the borders of countries. And I want to ask if you could further elaborate on that point but also elaborate on the challenges and dangers of securitizing women, as well as… Especially today when we see greater involvement of women in security decisions, how do we approach involving women in these security decisions but also refraining from securitizing women? And what’s the balance there, what’s the approach? Thanks.

Murabit: Next.

Audience 2: Both Ayaan Hirsi and Salman Rushdie of course are still under fatwa of various kinds that prevent them from freely appearing at casual meetings like this one. I was curious as to how one addresses Islamic jurists with regard to the iniquitous nature of some fatwas.

And also I’m curious as to, given the deep tradition of environmental law in Islam, reflected for example in the debate over water policies in Medina or Mecca or wherever, how that longstanding interest in the equitable division of environmental resources can be mapped into the Western conversation.

Zuckerman: So, a brief response to the gentleman and to Natalie’s question. We are unfortunately missing friends from this panel, including Intisar Rabb, who is a scholar of Islamic jurisprudence who’s at Harvard Law School. She got a better offer, which was tonight’s Eid celebration at the White House. And occasionally, Obama trumps even us.

But she works on a remarkable project called SHARIASource that looks at the wide variety of religious interpretation, and really celebrates the diversity of Islamic jurisprudence as one of the great strengths of the faith. And she’s going to be at the Media Lab at some point this fall. I would just ask that you look at the calendar, and if you’re interested in that topic come and see her as well, because that’s really her area of interest.

The question that I wanted to ask, I was really struck by your analysis that since the 1970s this very conservative Saudi vision of Islam has had a great deal of promotion through satellite channels, through networks of schools… I’m curious whether there is the possibility for alternative visions of Islam, more progressive, more feminists visions of Islam, going after that same sort of PR campaign. Where would that come from? How would we start that? And and is that too simple a solution to the problems that you’re so rightly posing today.

Murabit: So, I’ll start actually by first answering your question about really following the path of the 1970s, and I think it’s actually quite difficult. Because the landscape is a lot less focused. Back then if you had one radio station—and in many parts of the world you can still actually have one radio station and reach everybody within that community. But now you’re also competing with numerous forms of media, and numerous voices. And that tends to dilute the credibility to a lot of people.

So I think it’s a lot more difficult to do it with the speed and efficacy that Saudi Arabia was able to do it. And also there is the inherent credibility of being Saudi Arabia. Of being the most holy place in the world. So it it tended to lend the scholars that came from there credibility and support, and the financial support that came from the political arm was key. And I don’t think that we currently have anything which competes with that. I do think that right now in Islam, I think for the first time a lot of scholars have been forced to look at it. To look at the interpretations a lot more closely.

And you can see about two months ago, over 7,000 Islamic scholars released a statement which completely opposed extremism and supported peace and security, etc. And I think it’s the first time that they’ve actually had to be held accountable for in many ways a lot of their actions and the actions of their institutions which have supported a lot of these violent acts, and actually internally start saying okay, so what can we do.

And I think that is how this will have to happen. I think it will have to actually be through existing, established institutions taking accountability and saying, “We’re going to change what we’ve been saying, and we’re going to actually recognize that we have to have religious accountability rather than political power.” But also from civil society gaining strength within the region. And I think from the fact that we do now have different platforms that we can speak from. So you’re going to hear a lot more voices that you haven’t heard in the past.

The question on the securitization of women actually is a wonderful question. Women as borders is something that we’ve seen since the beginning of conflict. If you wanted to invade a country, you were advised to rape the women so that they could have your offspring. Your offspring would not be as willing to fight you in the future. So it was almost a long-term peace process. And so women have often been seen— Because they are the bringers of…whatever, you know, ethnicity, religion, nationality that you are, right? And so they hold a significant power simply in their ability to propagate a group.

Now, in the securitization of women, which is actually since 2000 the United Nations had the Women, Peace and Security resolution which actually stated that women were key agents in security but they also had key vulnerabilities in conflict. And that’s actually been a guiding principle for a lot of women’s rights organizations and activists, myself included, on how we gain access with policymakers to be speaking about women’s inclusion in peace and security. Because prior to then we didn’t have any official documentation which provided us that kind of authority or credibility.

The problem with the countering violent extremism and securitization agenda is that in the past two years, with the priority of countering violent extremism, a lot of research has shown that the degradation of women’s rights is actually the very first indicator that extremism, and particularly violent extremism, will happen in a country or region. And that the very first people who know about it are the women.

So the women will tell you two to three years before it happens, “Bel Haddadi[sp?] said he said he’s going to come and he’s going to start breaking down our walls.” Two or three years before it happens, “We can no longer drive in the night.” “People are telling us what to wear.” “They’re trying to segregate the universities,” right? And the issue here is now the global security complex has decided okay, so if women know this two to three years before, and research is showing that what they say means violence will happen in the long term, we need to start talking to the women.

And so they’ll start speaking with a lot of women’s rights activists, which is a wonderful thing. The problem is in the security of those women when they talk to the global community, right. So those women will go and have a meeting with somebody who comes in a bulletproof car, and they’ll go back to their community where everybody knows their name, knows where they live, and knows how to hurt them.

And so you find a severe increase in the assassinations and in the silencing of women’s rights activists in the region, because they’ve dared to speak up about things without being offered protection. So securitization becomes very very dangerous if we don’t provide the structural capacity to actually support the people on the ground who we’re asking to risk their lives, to be taking these steps to create the kind of cultural and social change we need within women in Islam.

Khan: I think at the same time, just add to that, we have to also take a look at the securitization of the Muslim woman in the West. If one takes a look at the political landscape in Great Britain, groups like the EDL (the English Defence League), Britain First, even BNP, the ban the burqa has been deployed by all of them in their political campaigns because of the danger of the Muslim woman wearing the burqa. What is she carrying with her? Is she a threat to your safety, to your security? Not from a cultural standpoint anymore, but coming into an area and detonating something. So it’s interesting to see how there’s that securitization element that’s going on.

Regarding your question on alternate tropes of Islam, I think that Saudi Arabia for a long time has been a Jenga game. And as people are now starting to extricate each piece from the overall edifice, there is some promise. Otherwise Saudi Arabia has been very effective in allowing people to tacitly see equal signs. Saudi Arabia is in Arabia, is in the abode of Islam, is Islam. And so if you start taking out those equals signs, then it puts their authority, or the perceived authority over people, in a precarious situation.

And lastly, the question that you asked which I think is very important, how to engage with with Muslim jurists. First of all, there is a huge amount of debate and dialogue going on among qualified scholars already. I think some of the problems that we find is on the margins, where people are pseudo-scholars, and those people who are not themselves trained in the Islamic science of jurisprudence. They’ve just simply stayed at a Holiday Inn Express and think that they are in fact a jurist.

What we find is also an inappropriate presumption made by a lot of Muslims that they are bound by every fatwa that comes out. First of all a fatwa is an advisory opinion. It is not a verdict. And the only people bound on it are those who are under the jurisdiction of that fatwa. Which of course makes it very difficult if you’re living in the United States to say that I have to be bound by something coming out of a traditionally Muslim country.

Lastly, the point on environmental resources. This is a huge issue because of of course water rights. And here again you find the kind of disillusionment happening when it comes to civil society, to the decision making that their governments are making when it comes to the exploitation of environmental resources. It is a huge area of debate. Unfortunately it is a debate that is being suppressed in a lot of parts of not just the Muslim world but even more globally.

Murabit: So, thank you for letting us solve all the global political and religious problems. We’ll be here all day to answer any [inaudible].

Zuckerman: Thank you so much to Alaa and Saeed. Just a fantastic panel. Such great food for thought.

Further Reference

Session liveblog by Natalie Gyenes, Willow Brugh, and Sam Klein.