Paula Gaetano Adi: I want to thank of course everyone for being here again, and Damian for putting this together. My name is Paula Gaetano Adi and I’m an associate professor here at RISD in the division of Experimental and Foundation Studies. And I’m here to introduce our next panel, that is titled Liberatory Aesthetics for a Just Transition? And it was formulated as a question mark rather than an affirmation, with the hope that we could really instigate a much-needed conversation about the role of aesthetics in shaping more socially and environmentally just futures, and in particular the ways in which the Green New Deal could bring us an opportunity to rethink and decenter the aesthetics and cultural production that had emerged out of the dominant imaginaries of white US-centric environmentalisms.

So for that, I’m just going to introduce our three panelists and our respondent here. I’m going to do them all, so that I can just be out of stage and allow them to speak.

We have Yuriko Saito, who is joining us to speak about the aesthetic experience of everyday life and the many ways in which our daily aesthetic reactions form preferences, judgment, design strategies, and courses of action. Professor Saito is a professor emeritus of history, philosophy, and social science here at RISD.

Artist and designer Anastasiia Raina will introduce us to her posthuman aesthetic and will invite us to speculate and imagine just transitions for our cyber future, or cyborgian future I’ll say. And Anastasiia is also a RISD person. She’s an assistant professor in the department of graphic design.

And lastly it’s a real great joy for me personally to invite Dr. Priscilla Ybarra, from whom I’ve learned everything I know about Chicano literature, I guess. In this panel Dr. Ybarra will show us how Latinx cultures hold the potential to make visible key aspects of the exploitation of the Earth and how the mainstream environmental fails to account for the diverse environmental ethics at work in communities of color, including indigenous and Latinx people and scholars. Priscilla is an associate professor of English at the University of North Texas, and she’s the coeditor of Latinx Environmentalisms: Place, Justice, and the Decolonial. And you can read more about everyone’s bio…there’s more details of their bios in the paper that you have there.

And our respondent, lastly, who’s going to give us a nice summary at the end of this panel is Nicholas Pevzner, who is a full-time lecturer at the department of Landscape Architecture in the University of Pennsylvania.

So with that I’m going to introduce Yuriko to the stage. Thank you.

Yuriko Saito: Well thank you very much for inviting me to this wonderful panel, out of my retirement. And it’s my pleasure to be here. And one of the disadvantages of going after the morning sessions is that so many wonderful things have been said, so I feel a little bit… Well, anyway. And also, my talk is on environmental aesthetics and everyday life, so what I’m going to be talking about is very very mundane. So I hope you’ll bear with me.

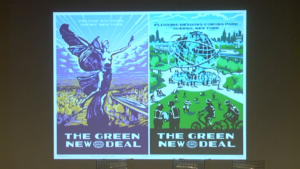

It is commonly recognized that artistic strategies are effective in promoting social, political, and religious agendas. We only have to think of the popular music accompanying the American civil rights movement, RISD’s own Shepard Fairey’s Obama poster and “Yes we can” campaign (by the way, he was one of my first students here), and the utilization of arts and media by Nazi Germany and today’s terrorist organizations.

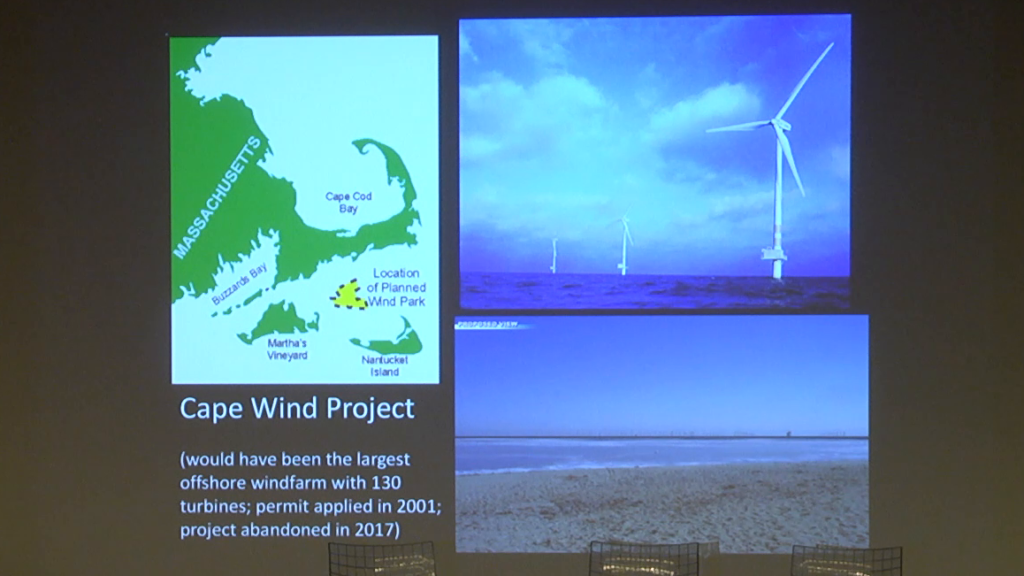

What is less recognized is that many decisions and actions we make in our daily life are also guided by aesthetic preferences and judgments. In the United States today unfortunately, the popular aesthetic taste seems to work against the ideals of sustainability and justice proposed by the Green New Deal. Green objects and practices are often rejected for aesthetic reasons. The prime example is wind turbines. And we talked about this a couple times already.

Take Cape Wind Project, which was never realized. The talk given at RISD by the head of this project, and my subsequent research, confirmed that the public outcry over this proposal was primarily aesthetic. Wind turbines in the ocean are considered to be an ugly eyesore that destroys a pristine natural beauty. The power of the aesthetic to make or break a project is surprisingly strong. However this initial bad news also suggests good news. That is, this power of aesthetics can be harnessed to support the environmental goals outlined in a Green New Deal. Indeed I believe it is imperative that an aesthetic paradigm change accompany the Green New Deal initiatives so that supporting and practicing sustainability and justice can be aesthetically enjoyable rather than denying pleasure. The aesthetic appeal of objects and practices is more likely to encourage us to promote, protect, and care for them than if we do so purely out of a sense of duty.

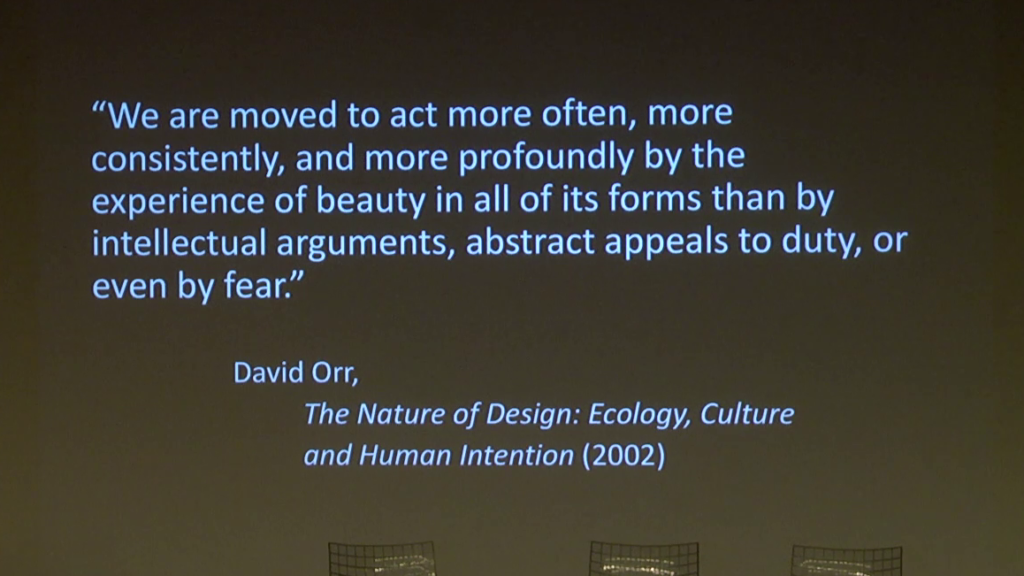

As pointed out by David Orr, We are moved to act more often, more consistently, and more profoundly by the experience of beauty in all of its forms than by intellectual arguments, abstract appeals to duty, or even by fear.

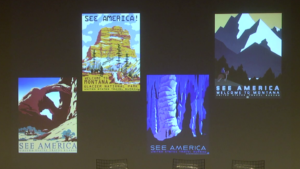

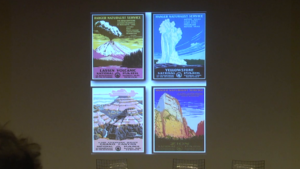

Because of the Green New Deal’s obvious reference to the original New Deal, as reflected in the posters, I want to examine the aesthetic implications of some of its legacies. One of the best-known programs of the original New Deal is the See America First campaign that was designed to promote tourism of the American national parks. True to the original purpose of national parks to protect sublime and mistakenly-regarded as untouched wilderness, these posters highlight the grandiose landscapes of the West to characterize what is distinctive of this nation.

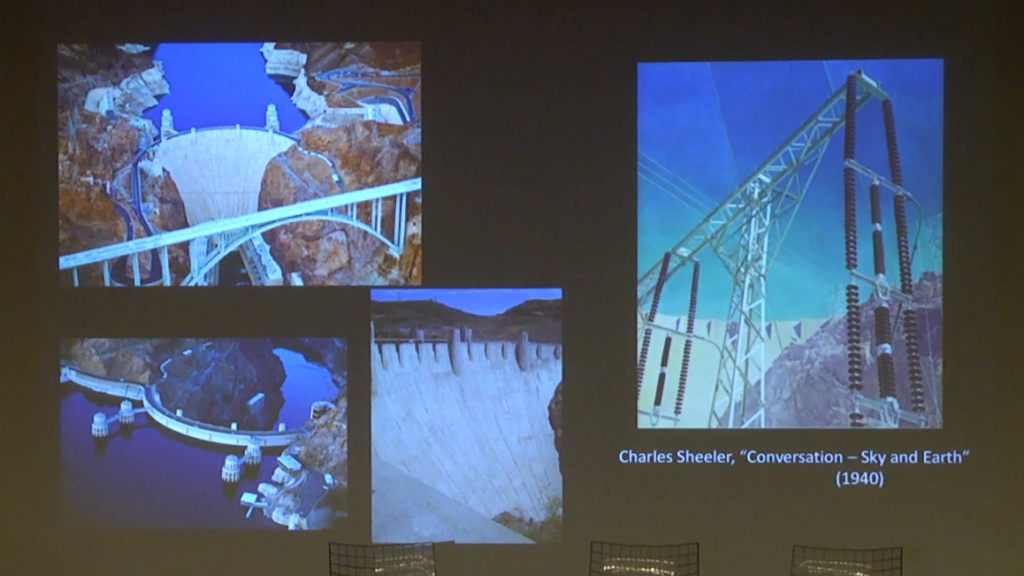

This American sublime was further enhanced by another well-known tourist destination of the New Deal, Hoover Dam, which was also referenced before. Not only was it a technological wonder but also a carefully-crafted landscape to compel a maximum dramatic affect. The visitors were awestruck by the tangible evidence of human control over nature, which helped instill a sense of optimism, as illustrated by Charles Sheeler.

This distinctly American landscape aesthetic was thus created by focusing on the dramatic and the extraordinary, often places away from our everyday environment. In comparison, the general populace remained indifferent to less-dramatic landscapes such as prairies, wetlands, and our backyards, making them vulnerable to exploitation and development. Aldo Leopold’s land ethic and aesthetic are thus concerned with the fate of those vulnerable lands.

There are those who are waiting to be herded in droves through “scenic” places; who find mountains ground if they be proper mountains with waterfalls, cliffs, and lakes. To such the Kansas plains are tedious.

The weeds in a city lot convey the same person as the redwoods.

Aldo Leopold, A Sand County Almanac (1949) [slide]

The legacy of this scenic aesthetic still remains, as it is easier to gain public support and funding for protecting awesome-looking species and landscapes compared to other nondescript species and landscapes.

In addition to creating this quintessential American landscape, the aesthetic of places away from our everyday environment, the original New Deal was also responsible for establishing a landscape aesthetic closer to home. The green turf became a signature feature for various public works projects such as urban parks and playgrounds, which also provided the aesthetic norm for domestic landscapes.

Accordingly, in the 1930s, many articles appeared to advise homeowners how to produce and maintain a perfectly-smooth green carpet with no weeds or brown spots. Furthermore, this task was often associated with civic duty and work ethic.

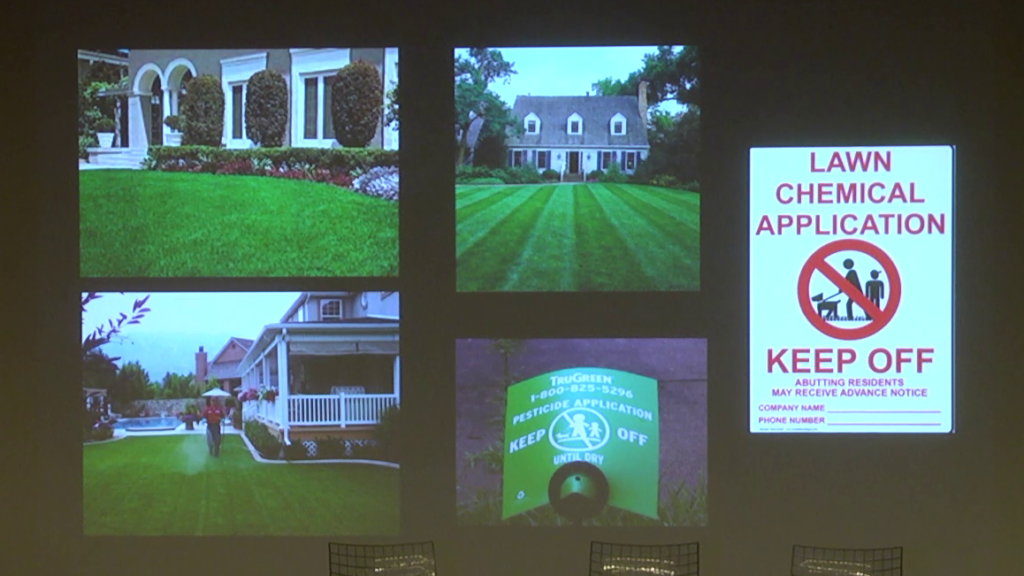

Today we know the heavy environmental cost incurred by maintaining a lawn, particularly because this aesthetic ideal was adopted without considering the specific geographical, cultural, and climatic context.

We also need to be aware of another legacy of the original New Deal era promoted by industrial production as a way of creating more jobs. In 1932, Bernard London, a real estate broker, penned an influential essay extolling planned obsolescence titled, “Ending the Depression through Planned Obsolescence.” He proposed that the government mandate a relatively short lifespan for all manufactured products, and the consumers return the product at the end of its life to be disposed of, regardless of its condition, and gain credit toward purchasing a new product. Promoting more industry production is necessary for the economy and job creation because, according to him, the problem underlying the Depression is that People…are using everything that they own longer than was their custom before the depression,

thereby disobeying the law of obsolescence.

I don’t know where the law comes from.

I find it rather fascinating that he characterizes obsolescence as an aesthetic matter, foretelling the contemporary notion of fast fashion. When he describes how people used to replace old articles with new for reasons of fashion and up-to-dateness

because furniture and clothing and other commodities should have a span of life, just as humans have. When you used for their allotted time, they should be retired, and replaced by fresh merchandise.

I couldn’t help thinking about people, too.

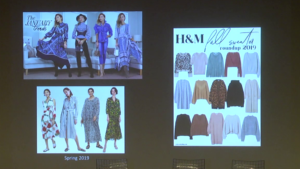

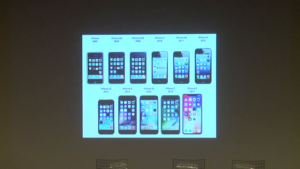

For today’s fast fashion, newness is a desirable quality in two ways. One sense of newness refers to being up-to-date and fashionable, as mentioned by London. Today’s frenzied pursuit of the most fashionable and up-to-date is well-documented, particularly in the apparel industry and high-tech industry. Today’s new style is sure to be replaced by another trendy style tomorrow, creating a host of problems including resource depletion, environmental harm, and human rights violations where fast fashion items are manufactured and eventually dumped. Although artificially-manipulated by the industry, this fast fashion taste in favor of the fashionable or trendy is a powerful aesthetic persuader to direct consumers’ purchasing decisions.

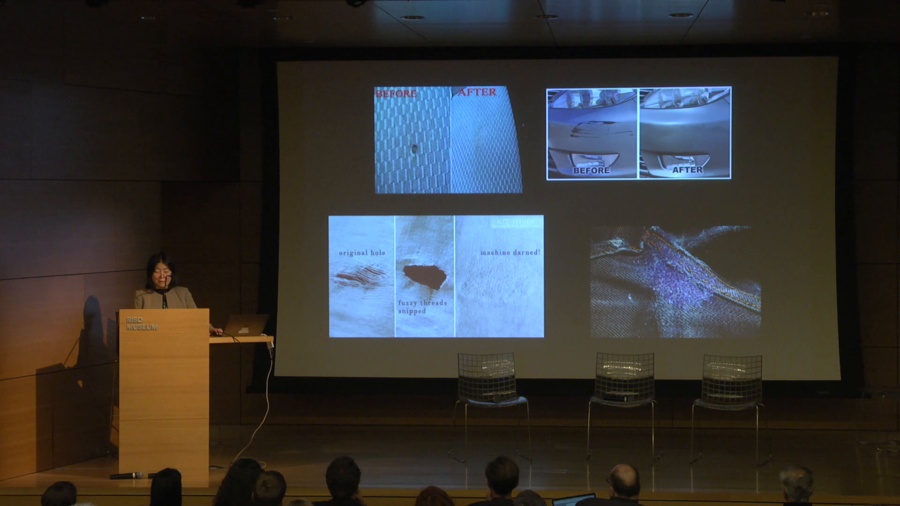

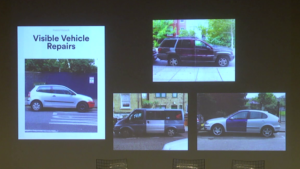

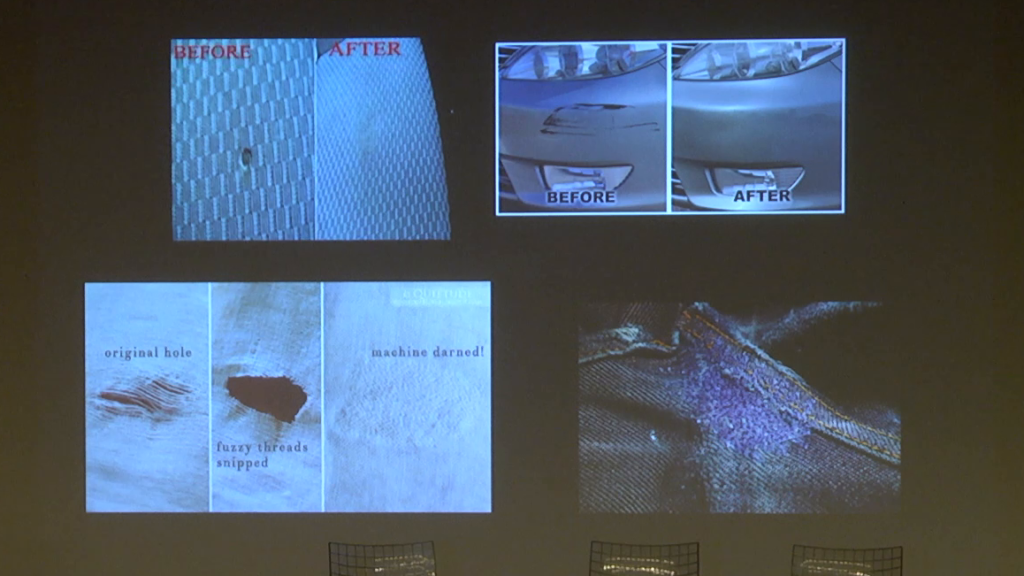

The other sense of newness fast fashion pursues privileges objects that are free of inevitable aging effect due to wear and tear and damage. This aesthetic desideratum encourages consumers to discard old objects in perfect working condition in favor of the brand new ones, except for items like well-seasoned jeans and tools. Furthermore, this aesthetic obsolescence is exacerbated by the difficulty, even the impossibility, of repair. Unrepairability of many products today regards no longer functionality but also the smooth, uniform, and slick surface appearance that does not tolerate scratches and dents.

Even when repair is possible the preferred mode is invisible repair that hides the signs of damage and repair. Those of you who are at RISD know the wonderful exhibit at RISD Museum last year on the notion of repair, which featured both visible repair and invisible repair. It was wonderful. There is a booklet to go with that. It’s called Manual, a RISD museum publication. And I really encourage you to take a look at it.

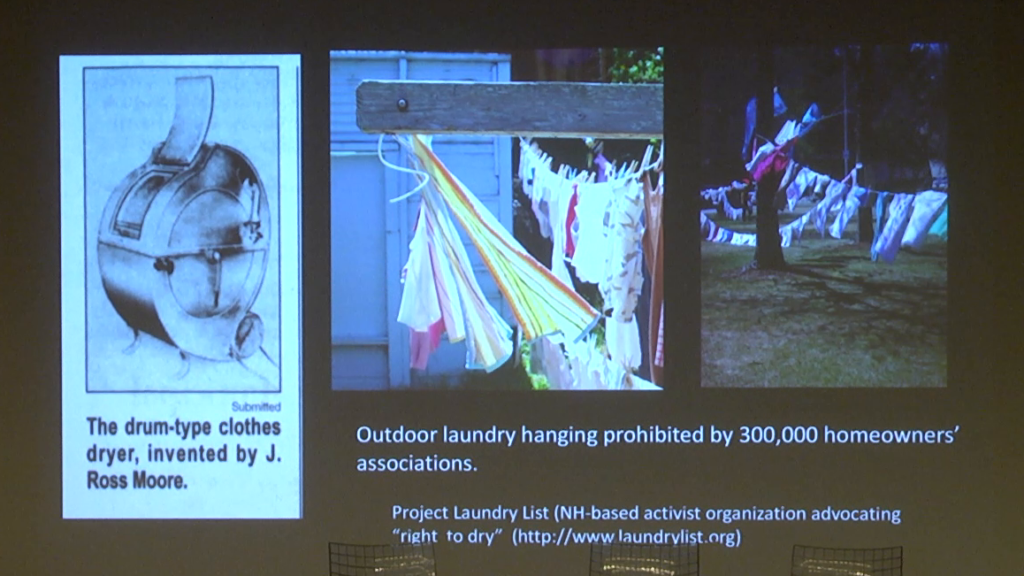

Another aesthetic consequence of promoting individual industrial production under the original New Deal era regards clothes dryers. First invented in 1938 by J. Ross Moore in North Dakota, of all places, to address the problem of drying laundry outside in winter there, it was soon promoted by GE as a means of freeing housewives from the time-consuming and weather-dependent drudgery of hanging laundry outside and supporting them to join the workforce outside of home. Outdoor laundry hanging soon became associated with poverty. Today it is estimated that 80% of American households own a dryer, considered to be the second most energy-consuming home appliance next to the refrigerator. What concerns me is that as of ten years ago, 300,000 homeowners’ associations in the United states prohibited laundry hanging, because it is considered an unsightly eyesore. So an aesthetic reason.

So these are the bad news regarding the aesthetic implications of the original New Deal program and the long-lasting legacy of that era. The question then is how the Green New Deal can and should address this bad news. In light of the rather surprising power of aesthetics, I don’t think we should dismiss its role in guiding our decisions and actions. Instead, we should harness its power to help shape the future outlined by the Green New Deal. It is true that aesthetic matters are the prime candidate for people’s right to exercise individual liberty. We can not, and should not, legislate aesthetic taste. However, the fact is that aesthetics has been operating as hidden persuaders effectively. And, Richard Thaler and Cass Sunstein point out, There is…no way of avoiding nudging in some direction, and whether intended or not, these nudges will affect what people choose.

Fortunately we don’t have to start from scratch when trying to shift the aesthetic paradigm to align with sustainability initiatives. There have been promising grassroots movements as well as art projects already, and these bottom-up initiatives should be supported and developed even more. One of the predominant themes embraced by the conventional aesthetic implied by the original New Deal and its era is uniformity. And actually, listening to Daniel’s presentation about comfort this morning, it struck me that the notion of comfort by air conditioning and so on—that’s also sort of aiming for consistency and uniformity of the temperature and so on.

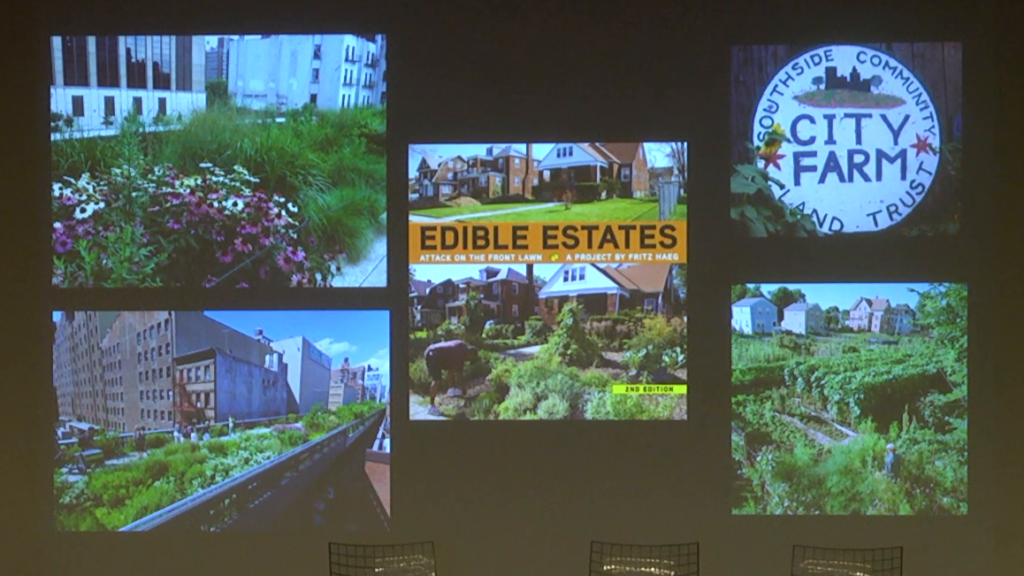

For one, this uniformity guides the monoculture aesthetic of green lawns. In response, wildflower gardens, community gardens, and edible estates proliferating today challenge this aesthetic desideratum by celebrating the cacophony of various sensory qualities provided by diverse plants. These gardens are also lively and vivacious due to the visits from birds and butterflies as well as community members, passersby, and neighbors, who become engaged in conversations and caretaking. In light of their landscape aesthetic, the conventional monoculture of green lawns starts appearing eerily sterile and devoid of life.

Countering the aesthetics of uniformity can be extended to farm produce as well. In response to the fact that one third of fresh produce in the United States was thrown away for aesthetic reasons, some supermarkets are selling them by featuring their unique aesthetic characteristics. The right side, by the way, that’s from a French supermarket chain. But the left one is American, Pittsburgh-based I think.

The norm of uniformity also underlies the industrial production because the products at the end of the assembly line must be consistent and perfect. What some thinkers call “productionist bias” discourages consideration of the life of the object after production that continues to evolve with the inevitable aging process, breakage, and interaction with the user.

An alternative, “broken world thinking” is proposed to highlight erosion, breakdown, and decay, rather than novelty, growth, and progress as the primary focus

. While erosion, breakdown, and decay all have a negative connotation, the new aesthetic paradigm can turn them into a springboard for creative, imaginative, and aesthetically appealing solutions that embrace diversity and imperfection.

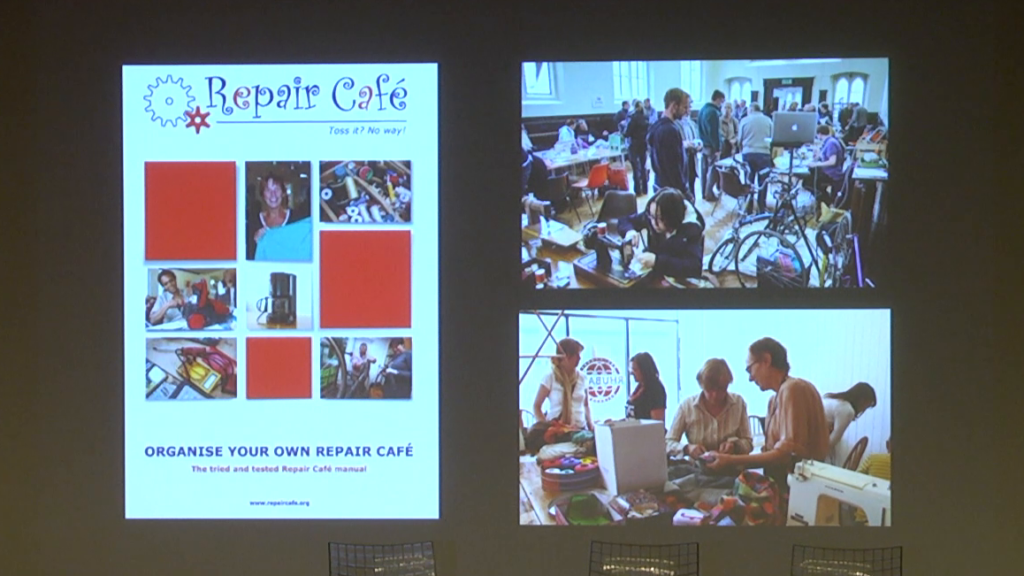

In this regard, consider various grassroots initiatives that promote the practice of repair. Repair Cafe, established in the Netherlands in 2009, is slowly but surely spreading in the United States with ninety-eight locations now. To date, twenty states have passed right-to-repair legislation to counter the industry practice of making repair difficult or sometimes impossible and forcing consumers to purchase new products.

What is noteworthy from the aesthetic point of view is that today’s repair activists promote visible repair, challenging the conventional aesthetic that favors objects that are in mint condition or hide the signs of repair.

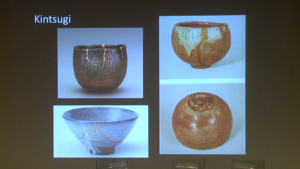

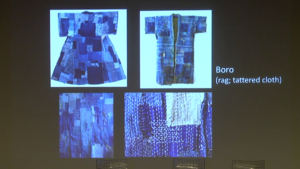

Often inspired by the Japanese tradition of kintsugi (repair by gold), and boro (tattered clothes), not only can visible repair have its own aesthetic appeal but also it cultivates an aesthetic that celebrates our active engagement with the material world.

Activists in support of outdoor laundry hanging, spearheaded by Project Laundry List’s right to dry initiative helped pass legislation banning prohibition of outdoor laundry hanging in nineteen states to date. The arguments in support of outdoor laundry hanging include not only the environmental benefit, but also the various aesthetic appeals such as the fragrance of dry clothes and the joy, rather than the drudgery, of sensory engagement with the sunshine, wind, and fresh air.

Thus, aesthetics has a critical role to play in supporting Green New Deal’s environmental initiatives. We can learn from the original New Deal that the aesthetic paradigm resulting from its political economic initiatives has had significant power to shape people’s everyday life. It therefore behooves all of us as citizens and consumers to raise awareness about the role aesthetics plays in our everyday decisions and actions, and to cultivate both aesthetic literacy and vigilance.

Finally, and most important, the artists and designers have both the opportunity and responsibility to invite citizens to embrace and celebrate the new aesthetic paradigm that supports diversity and imperfection. Thank you.

Further Reference

Climate Futures II event page