Frank Pasquale: So I’ll start with the subtitle of my paper, which is about reputation and search. And we heard Tarleton in the last talk talk about media studies and the study of the algorithm. And the sense that the algorithms were increasingly important in terms of how we are known by the world, and how the world knows us. And for me I try to translate this into the ideas of search and reputation. Essentially search…the study of search, be it by people like David Stark in sociology, or economists or others, I tend to sort of see it in the tradition of a really rich socio-theoretical literature on the sociology of knowledge. And as a lawyer, I tend to complement that by thinking if there’s problems, maybe we can look to the history of communications law. And that’s been a lot of my work on Google and other sorts of search engines.

And the other side is the reputation side. This sort of existential experience of being searched for. And that experience, I try to look to norms of due process from law, in terms of if our reputation is unfairly constructed or that we have some chance to contest that. That we have some chance to understand what went on and that we can contest that.

The other thing that I wanted to note here is that where does the algorithm play a role here, right? Well the algorithm in some sense— There’s all these algorithms which we’ll discuss today in the financial context in my talk which are about interpreting signals. How we interpret signals about certain individuals? How do say traders at large investment banks, or people who’re making decisions for pension funds, how do they interpret various signals sent out by the market or the high frequency traders?

And another is sort of a thought about… and in terms of reputation, how are reputations constructed based on various signals that are assembled about us by particularly the credit bureaus, when processed through credit scoring or other forms of scoring?

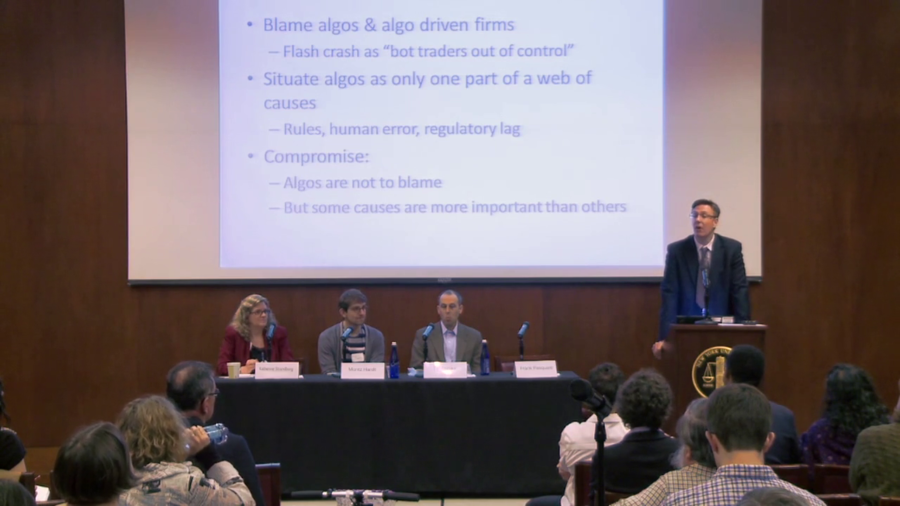

Now, one thing that I noticed as I was reading— And you know, I didn’t give them enough attention as I should’ve but I was trying to read some of the other conference papers. They’re very rich papers. And you see this sort of dialectic building in the conference papers in many contexts. One is to sort of say well there’s this literature out there that says “blame the algos and algo-driven firms,” this sort of separate, accountable entity. And that when you see something like the Flash Crash or the crash of 2:30 PM on May 10th, 2010, that you would see those sort of flash crashes as that’s bot traders out of control.

Now another group of theorists—I tend to think of Neyland’s paper and some others in this area, and Tarleton’s and others in this area, sort of come back and say, “Wait a second. You can’t blame the algorithm. No, the algorithm is just one part of a web of causes. There’s this very large…you know, just situated it,” and for example with our Flash Crash example we could say alright, there could be all these algorithms that sort of drive high-frequency trading or algo trading or other things. But the only reason why they had such disastrous effect is because of human error, and the rules, and say regulatory lag. Problems at the SEC, its budget is only a billion dollars and Mary Schapiro said that their computers are two decades out of date. She said that about three years ago so maybe hopefully they’re catching up.

But, I tend to think that—you know, I worry that essentially that might be letting the algo off a bit too easily off the hook? Or at least it’s not focusing us on where we might more fruitfully focus. So my compromise that I’m going to try to get across in each of these different areas in my paper is that algos are often not to blame but some causes are more important than others.

And the metaphor I like to use is something from Nancy Krieger, an epidemiologist. And she says there are many situations where there are problems, and other epidemiologists say well there’s a web of causes. But Krieger always asks, “Where’s the spider in the web of causes?” And I’m not trying to say that there’s some sort of entity that’s actually orchestrating the problems, or the excessive profit-taking, or the the instability that we’re seeing, or the unfairness that we’re seeing in the areas that I’m discussing in my paper. What I am saying is let’s look very carefully at who benefits the most from these, and how they keep these systems in action.

Another group of metaphors that I think is very rich for this conference is… You know, we’re all aware of a Don MacKenzie’s an engine, not a camera-sort of metaphor, right, for various aspects of financial modeling and other things. So, he sort of gets us to say wait a second you know, these models that were used in the financial crisis that were ultimately sort of derived into algorithms or sort of used and formalized in algorithmic systems, that they did not merely reflect financial reality but they help create it.

What I’m going to try to say in this talk is to say the camera metaphor was bad and MacKenzie was right to critique that, especially in articles like [The Credit Crisis as a Problem in the Sociology of Knowledge]. But that the engine metaphor is not quite right because there is a fundamentally communicative dimension to these algorithms and the things that they’re communicating about, say people’s reputations and the value of different entities that are out there in the financial sector. So I’m going to compare them a little bit more to Photoshop. And a version of Photoshop where could be true, it could be false. And particularly a quote from Iris Murdoch where she said— I just love the quote where she said, “Man is the creature which paints pictures of itself and then becomes the picture.”

So let’s start with our first example in the paper, credit scoring and the type of picture that it’s creating about people. And so I’ll escape for a bit. I just wanted to try to show you all this one commercial. And I don’t know if the A/V is hooked up but let me see if it’s actually on. It’s not? That’s fine. Well I actually have the audio on my phone, so I can sort of try to sync this. We will see if it works. Are we ready?

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ea0bwbtWvWQ

Isn’t that heartwarming? Isn’t that wonderful, in the age of the algorithm we can still have human concern from these companies?

Unfortunately for poor Stan, what we find out from consumerreports.org is that creditreport.com is owned by one of the credit bureaus, Experian. That the score they sell you is not the FICO score that as Martha has shown in her terrific, rigorous work is so important. But rather it’s something else that really…maybe it’s relevant, maybe it’s not. And the charge you a dollar…that’s very charitable. But then, the fine print says that after a seven day trial you’ll be charged twenty dollars a month. So, poor Stan.

So coming back to our sort of metaphor of creating reputations and the web, what we see is essentially this sort reputation creation mechanism where at least for some very disadvantage or marginal people, they’re sort of drawn into this discourse and this way trying to create their own reputation or trying to take control over it. But in fact if you went into this, maybe if you are as financially troubled as Stan, that $204 a year you might end up getting charged might really hurt you. And you know, that might be a real problem there. And I’ll get a little bit more into this idea of algos.

Now, let me talk a bit. Because I know the paper’s a little lopsided toward credit scores. What I want to try to do with this slide is just talk about what are the problems that are across all these different areas. And the troubling aspects of the financial firms’ use of algorithms I think are are at least six-fold—there might be more.

One is this nature of secrecy, okay. Because the algorithm is secret in say credit scoring, people might say oh you know, should I pay off this bill with a payday loan and pay I don’t know, 80% interest on that payday loan or whatever it is? Or, should I not take the payday loan and then take the hit on this bill? Well you can’t really tell a lot of the times what would be better, and that’s very troubling. And I’ve talked to people in the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau who I think are troubled by that as well. It’s very hard to know.

Second is that there’s sort of a self-fulfilling prophecy aspect of it. If you get a 580 score, that score’s essentially communicating non-creditworthiness. But also when you have a 580 score you may have to pay a 15% interest rate, which in turn feeds into non-creditworthiness because it’s hard to make a 15% interest rate, right. That’s really hard. So there’s a self-fulfilling prophecy aspect of it.

Another aspect of it is this high-volume processing. The credit score you know, again pointing to Martha’s work, came up in the context of a lot of these securitizations. It comes up in the desire among a lot of lenders and others to sort of make a lot of loans all at once. And we have to wonder who exactly is benefiting from that.

A fourth aspect is this government/firm symbiosis, okay. It’s not as if this is sort of a creature of the market and then it sort of is being regulated from the outside. And the regulation of the credit scoring system is so sort of pervasive, under things like the the Equal Credit Opportunity Act, other sorts of aspects of regulation here, that there’s something like in the financial sector. And we see this in a lot of the “too big to fail” discourse. A real intertwining between government and the private sector. And this is something that I find very usefully described by Charles Lindblom as the concept of circularity in his work on political economy. More colorfully evoked by Hanna Pitkin’s book on Arendt as “the Blob.” There’s this blobbish aspect of sort of revolving door regulators, and financial firms, and sort of rules that are meant to sort of create this patina of regularity and fairness but that ultimately do very little, I find, in each of these areas.

Another example is overconfidence because the data underlying all of this often is very bad. I cite in the paper a report by Steve Kroft at 60 Minutes where he talks to a number of people that worked at the credit firms in order to hear from people who wanted to challenge aspects the data that was put into their score. Many of them simply said the creditor was always right. That was the nature of the decisionmaking process. It was a Potemkin process, you know. And this is very troubling. And I’ve never seen any sort of convincing retort by FICO or by the credit bureaus to reports like that. Mike DeWine at the Ohio Attorney General’s office also is doing this. I cite lots of things like this report Discrediting America in the paper.

And I worry ultimately…you know this question of self-reference comes back to self-fulfilling prophecy. It’s more of a distinctive concept in the other areas. But I really worry about that as well.

Now what about these six aspects in another context? Let’s say the mortgage-backed securities and securitization? You might’ve seen this NPR reporter who got fired for holding this sign which said, “It’s wrong to create a mortgage-backed security filled with loans you know are going to fail so that you can sell it to a client who isn’t aware that you sabotaged it by picking the misleadingly-rated loans.” And the question I think for our purposes is, are the people—the quants in these firms—do they have any independent power to say, stand against if they see a situation like this materializing? Are they too isolated to even recognize what they’re doing, what it’s being used for? I know that in Jonathan Zittrain’s work when he looks Amazon’s Mechanical Turk, he worries about situations where you could have all these Turkers—you know, the Mechanical Turk workers that’re all distributed under Amazon’s labor distribution system—who each particular task they do they might think, “Oh, this is great.” But then it turns out that as they’re aggregated it does something really bad. And that’s the question I think we often have to have about people who are involved say as quants or sort of developing algorithms at these firms. You know, do they really understand what’s going on—can they?

When we talk about those six problematic aspects of algorithms here, again there’s a lot of secrecy. Now in terms of these mortgage-backed securities it wasn’t necessarily the nature of the securitizations themselves. That was more about complexity. But what people didn’t understand was that they only made sense in many cases because of what’re called credit default swaps. And these credit default swaps were an utterly opaque market. Nobody really understood what was going on there, I feel. Or the regulators—at least you can say that the people in charge did not really understand what was going on. There’s also an account of AIG, which wrote many of the credit default swaps, a book called Fatal Risk, talks about this push and pull between AIG and its accountants and other people in terms of actually understanding what was going on. But that secrecy was very problematic, and that is what let a lot of self-dealing flourish in the years running up to the financial crisis.

It was also about high-volume processing. It was about essentially trying to make as many loans as possible so that there could be as big a cut of fees as possible. There is a second-hand rationalization that would be we’ve got to get as many people into houses as possible. But really? I mean, I don’t know, it’s doesn’t sound terribly convincing to me. We can get into that a bit later on.

And also there’s overconfidence in the face of bad data. And I think the best example of that might be the credit rating agencies. We had a lawsuit by S&P where essentially there was a complaint about the about the S&P rating practices. And by the way, S&P always said about their rating practices, they said essentially, “We are objective. We are independent. You know, don’t worry that we’re paid by the people who are selling the securities. We are objective and independent.”

But then as the lawsuit comes out, and as we learn more and more about internal communications, we get quotes like, “It could be structured by cows and we’ll rate it.” We have people within the firm who sing “Bringing Down the House” to the tune of “Burning Down the House,” in terms of making fun of what was going on. I mean, it just seems as though this sort of thing is really problematic. And then, when they’re later called on this, and I think this is a point that Mordecai made in his comments earlier, or question earlier that you know, when they’re called on this and sued over liability, they’ve actually put out an answer that says that was, “When we said it was objective, that was puffery.”

And puffery is a legal concept where essentially…the legal concept there is that let’s say that I want sell you a car and I say, “Oh it’s the most awesome car ever.” And then it breaks down after three weeks. You probably can’t sue me for saying it’s the most awesome car ever because it’s very hard to really prove that that opinion was wrong. And so that’s the worry I have, and also it gets back to Tarleton’s point about the sort of, in the Google DNA when they say “we are objective and pure” and all the other things as far as the assurances about what we believe in— “This I believe,” you know. That sort of stuff. We worry about essentially if that can be cheap talk, right. And a lot of this is sort of a problem of cheap talk. Is the signal sent out, are they cheap? Because essentially they can all be sort of… Any liability for them could be deflected in the form of saying oh they were merely and opinion. That’s what S&P is trying to do now. They’ve got some of the best First Amendment lawyers in the world pushing their case. We’ll see how it works. They they may well be able to do that.

There are other levels of concern here about sort of models, and the nature of models, and modern securitization, and modern accounting, and finance. One sort of three-fold level of problems here is that often the modelers may not know the history, so you may bring in a whole bunch of people who say are brilliant physicists, brilliant mathematicians. And then you say, “Create some sort of models about the housing market based on this 1995 to 2005 data involving housing prices.” They might well tell you “Wow, they only seem to go up,” you know. But the question is you know, is that really a good thing to be basing your model on? And a lot of the modelers, they may well have gone…for physics, they may not know about the Great Depression, they may not have particular interests in other sorts of things in terms of where have housing prices gone in the past.

Another thing is that the managers don’t understand the modelers’ methods. So you can have a situation where essentially you know, I’m sure anyone who’s an attorney in the room has had the experience of maybe a partner telling you, “Hey, we really need this certain result in this memo.” And maybe you find a lot of cases on one side and a few on yours. But you know, it’s a hard dilemma, right?

And this could be the same thing for a lot of the modelers involved. They could face the same dilemma where essentially it’s sort of understood what they have to come up with. And so, if you have sort of plausible deniability among the managers, where they can say, “Oh. I had no idea that there was something problematic with the models they had.” That’s really a problem. And I think that you can understand a lot of corporate organization and corporate structure as ways of creating corporate veils, plausible deniability, other things like that. And the role of particularly complex algorithms or other things like that is to sort of create this patina of respectability, of mathematical rigor, over what may well be a process that’s overdetermined to simply sort of line the pockets of insiders and people at the top of the firm.

Another example too is that there can be these daisy chains of value, okay. So, ideally when chains of value are created or when value is created, we’d like to believe that it reflects something real about the world, okay. But in fact, and as I show in parts of the paper about securitizations, what might end up happening is that certain captive entities are sort of orchestrated to buy parts of different securitizations. And then once those captive entities buy them then it seems oh wow, people are buying. And then this sort of creates this type of again, self-fulfilling prophecy where everyone’s saying oh, that’s great, let’s all jump on this bandwagon. But only a few people on the inside know what’s really happening. And again, the models can be used as sort of ways of rationalizing that.

And sort of I feel this reaches a bit of a reductio ad absurdum in algorithmic trading, particularly certain types of high-frequency trading that I focus on in the paper. I tend to think that you know, the metaphor I try to use is this this concept of war and finance. So I have a quote in the paper from Milton Friedman, where Friedman says he was a ballistics expert, and he felt the often in the realm of ballistics in World War II you had to decide did you want to have a big bomb on one target where you knew people were? Or did you want to have say 300 little bombs? You know, divide your power over 300 little ones over all these different areas and have little impacts?

And this type of idea of the flexibility and malleability of force comes in in say the algorithmic high-frequency trading type of area. In terms of, you can sort of go for say one big bet on something. Or you can say have these methods where, to give one example say, someone could buy ten thousand shares of a stock and then could immediately cancel 9,999. Then could jump back in. And the question is what they’re trying to do is part of the strategy there, you know, to put it very simply in terms of that strategy, is you’re trying to create an illusion of a certain amount of value there. And when people are fooled…maybe they followed after you, but then you can come in behind and take advantage of arbitrage, this sort of temporary fluctuation of values created by your attack strategy.

So, this is a real problem. And the question might become well, what’s the big deal, they’re playing this game. It’s Ender’s Game in the finance markets or something, you know. BattleBots, as [Nanak] sometimes analogizes them to. But the problem is that the game… This gets back to the Blob idea of government regulator and regulated entity circularity. The game itself creates tons of money for lots of the folks in it. For example [Thomas] Peterffy, who was one of the leading people who were behind these sorts of…who was a pioneer here, you know. He was a pioneer to the point where he was told by the SEC that human beings had to enter the orders so the orders to be— He was told the orders had to be typed. So he developed sort of mechanical thumbs to type, and fingers to type in the orders. So he was this sort of real pioneer.

And you know, the people like him that have billions of dollars can put up ads where they say, “I grew up in a socialist country, and that’s why I’m voting Republican and putting this out on television.”

Now if you look at the sort of results of a lot of what the finance sector does, and the algorithms in it, it enriches a lot of folks who essentially want to say to you, and who want to create say, “Hey. If you’re looking for value in security, don’t look for it in government. Look for it in our algorithms and also in our sophisticated methods.” That may be puffery.

But really that is the problem that I see in a lot of these areas. And so my agenda for reform is essentially— And that’s towards the end of the paper. I get into this idea that essentially you’ve got a group of people that’re sort of trying to socially construct an expertise around what they do. And the algorithm plays a very important role in that social construction of expertise.

And I would say that my agenda for reform, to go on the reputation side because I know I’m running out of time, is that I would say— This is a very mild reform. Which is to say I just want to see experimentalism for open and contestable reputation creation, okay. Given that there’s this Blob issue of circularity where the government is so involved in the credit markets, why doesn’t the government say, “Hey let’s have an open source credit scoring system that we’re going to use in some situations.” I mean the conservative Jim Manzi talks about the importance of experimentalism. Let’s experiment.

And people are going to say, “Oh, they’ll game the model.” But first of all I kind of like Kathy O’Neill’s point. She blogs at Mathbabe, and she says let them game the model, you know. Let them game it because it’s essentially that important us. And she gives a lot of rationale there. Just mandate it in 1% of the contexts.

The other, and here’s a much more controversial point, is in terms of value in finance and all these securitizations and other things, and HFT that I talk about in the paper is, we’ve gotta go back to what FDR was choosing in the 1930s when we had the last massive crash. And, the path he took was disclosure, okay. He looked at Brandeis and he said, “We’ve got to disclose. We’ve got to essentially make sure everyone can understand what’s going on in the finance sector.”

The problem is the more I look at this problem…and you know, Dodd-Frank was based on this. The more you look at this the more you feel like this can be defeated so easily. It’s so easy to create complexity. We see even in the past couple of weeks in the House Financial Services Committee a coalition of all the Republicans and a number of Wall Street Democrats, banding together to sort of get rid of certain aspects of Dodd-Frank and and to sort of blow holes in Dodd-Frank, you know. And it’s just so hard to understand. Henry Hu’s article Too Complex to Depict? is particularly good on this topic.

There were other folks like Moley, Berle, and Tugwell who said we’ve got to actually correct the misallocation of capital.

And if I had to offer one positive vision for the role of algorithms and mathematics in finance, I would look at Sandor’s book Good Derivatives. He’s a very esteemed person in this field. He’s talked about the use of derivatives to sort combat climate change, etc. in the context of climate exchanges. He’s somebody that shows that essentially, the algos…let’s stop blaming the algos. Let’s create some public purpose behind them so that they can be utilized for better ends than enhancing bonuses for top managers. Thank you.

Further Reference

The Governing Algorithms conference site with full schedule and downloadable discussion papers.