Liz Jackson: Hello. ‘Stick this right here. [hangs cane off front of podium]

That’s me—short hair, smile, cane. Those are my words. Aren’t captions glorious? Let’s just stop for a second and admire them. Eh, they stopped.

Anyway I remember like a year ago I got this email from IDEO. They said they wanted me to come in, they wanted to talk. When I got there they said they had this technology that they had created that was intended to get disabled people hired. And so I said, “What disabled people did you hire to create this technology that’s intended to get disabled people hired?”

They said none.

Hadn’t even occurred to them that they were perpetuating the problem that they had set out to fix.

Not long after, they came out with a card game called Adapt-O-Pack. For brands who I sort of presume are interested in disability. They claimed the goal was to break down bias through play, but to me it looks more like a game for brands who are interested in disability but don’t really want to talk to disabled people. So it seems to me like we’re the bias that they’re trying to remove.

So why am I telling you this? Because I think we need to start thinking critically about things that we perceive as wholesome. Empathy has become a big business, and we ought to be able to examine it. Everyone’s always trying to diagnose disabled people. But I’m gonna have a little bit of fun, and I’m actually gonna diagnose all of you.

All of you are pathological altruists. It’s like Oprah says—and I think she’s the most pathological of all the altruists. Right? Your a pathological altruist, you’re a pathological altruist…everyone here, myself included, is a pathological altruist.

So what is a pathological altruist? Well it’s a person whose well-meaning efforts actually worsen the very situation they had intended to help. So, someone who stays in an abusive relationship for the kids is a pathological altruist. Animal hoarders are pathological altruists. The person who might actually kill you with kindness is a pathological altruist.

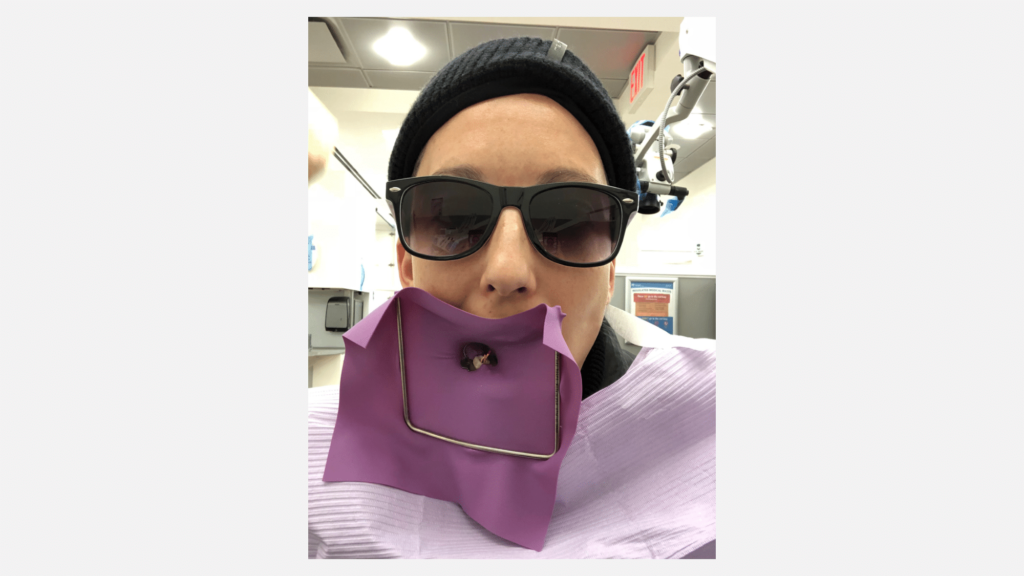

I’m here today to apply the phenomenon of pathological altruism to mainstream disability narratives. I went to the dentist. I mean it, I went to the dentist a few weeks ago. And literally as he was putting this dental dam—I’ll change the picture.

As he was putting the dental dam over my face, he asked me, he said, “What have you been up to?”

And I told him, [covering mouth with hand to muffle her voice] “I’ve been writing about my struggles with empathy.” I’d been writing about struggles with empathy.

And he said, “Really! I struggle with it, too.”

I don’t think you do.

And he posed this question to me, he said, “If a blind woman is crossing the street, do you offer to help and risk offending, or do you stay away and risk that she might hurt herself?”

And literally my mouth is propped open. I am numb as hell. And, I have a dental dam over my face. So I can’t ask the one question that I wanted to ask.

I get home that night, and I can’t hold it in any longer and so I shoot him an email and I say to him, “In this hypothetical that you posed, how did you know the woman was blind?”

And he wrote me back and he said to me, “You know, she was using one of those sticks.”

And it struck me that the very thing that told me that she was fine, she didn’t need any help, was the signal to him that she did.

The world has taught us that a disable— I probably should’ve put a slide here, but you can just kind of imagine me with my mouth agape. The world has taught us that a disabled body is nothing more than a body in need of intervention. And this is what designers do, right. We…we fix things. We design interventions. We dedicate our careers to it. We are here today because of our commitment to this process. We are seekers who develop our skills with rigor. Because we oftentimes want to be the best—there’s a certain glory in being a designer.

And so, I see the natural progression. Of course we’re gonna want to take and apply our highly-attuned skills to something that we think needs fixing. But there’s another side to it, too. I was recently talking to an administrator at a top design school. And she was saying to me that she dreads the start of every semester because she knows that there’s going to be a line of students outside of her office, wanting to fix her cane. But the thing is, is that she likes her cane. Actually it’s a walker. Sorry, that’s my cane.

So these students want to fix her walker. She likes her walker, she doesn’t think there’s anything wrong with her walker and what these students don’t realize is that they are telling her that there is something wrong with her walker and therefore there is something wrong with her. And I suppose that is how this feels, is that we—disabled people—have become a project or a topic. Design doesn’t see disability as a discipline or a craft. There is no rigor. We are nothing more than your portfolio enhancer or your brand enhancer. We are a symbol of your altruism. And that, among so many reasons, is why the very systems that have been put in place to support us end up doing more harm than good.

Let’s think about this in terms of design thinking, which I’m sure you all know is an approach to design that gained steam in the 1960s. It was created, in essence, by white men who had no equals, right. They were at the top of their professions. They were filling millions of homes around the world with products, and they were aligned with the greatest institutions in the world. And what they started realizing was that design wasn’t reaching everybody and so they created this system built on empathy to begin filling in those gaps.

And while much good has come of it, it has inadvertently fueled the narrative that disabled people are recipients rather than drivers of design. This is why I propose a new approach to design thinking that I call “design questioning” because I believe that we we’re finally able to question the systems that disable us, everybody involved stops seeing our bodies as the problem.

So design thinking, right, it starts by building empathy, right. So a designer goes in and through observations and interviews, they learn about the user. But to a disabled person it can little feel a little bit less like empathy and a little bit more like designers are coming in and they’re gleaning our ideas and our life hacks and then they’re selling them back to us as things that are inspirationally done for us without ever giving us credit.

It makes me think about the story of OXO kitchen products. Does anybody here know the story of OXO? So, if you go on the web site, you’ll see a story. And the basic premise is Sam Farber saw that his wife, who had arthritis, was having a hard time peeling a carrot so he decided he was going to make a better peeler for her to use.

Well, it struck me as interesting because I just always thought there was something a little bit off about that story. And I one day decided to call up Betsey Farber and say, “Betsey, you know, can you tell me about OXO from your perspective?”

And the very first thing she said to me was, “I’m going to go down in history as being Sam’s lowly, crippled wife and it was actually my idea in the first place.”

But back to design questioning. So, Step 2 of the design thinking process is defining the problem. But because disabled people are rarely able to lead, it often becomes us that’s defined as the problem rather than the problem being defined as the problem, so it becomes about what we can or can’t do rather than how something does or doesn’t work for us, right.

So you have our insights gleaned. We’re defined as the problem. And then designers enter this iterative process of ideation, prototyping, and testing, which I say leads to the unacknowledged sixth step of design thinking, or as I call it, “design thanking” because we’re expected to be grateful for that which has been done for us.

For example, have any of you seen the recent Nike ad, the one where they signed their first-ever disabled athlete—it came out a few months ago. It’s interesting. So, it’s not even four seconds into the ad when Nike tells us that Justin Gallegos suffers from cerebral palsy. This is on World Cerebral Palsy Day.

Does this look like somebody who is suffering to you?

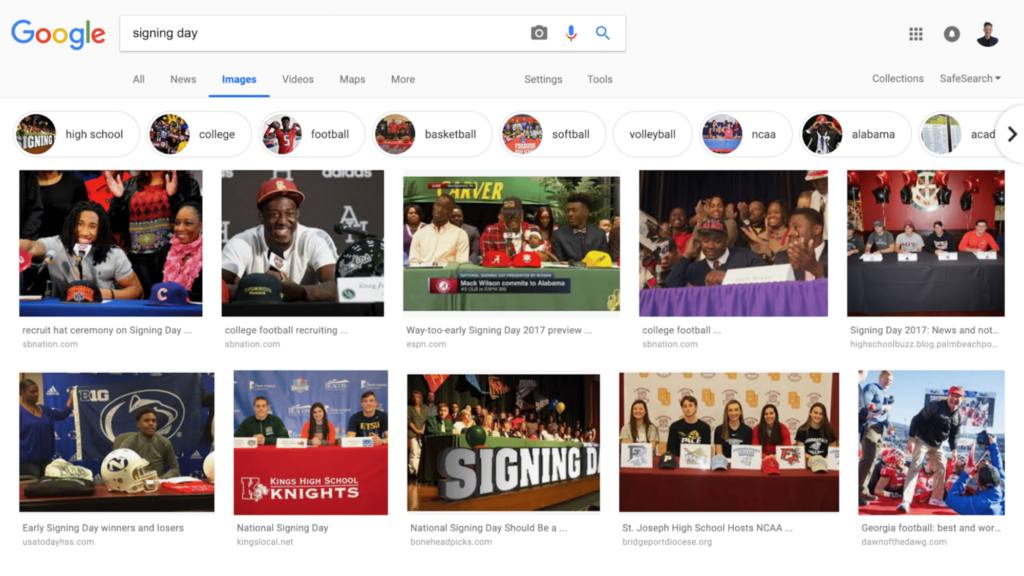

Anyway, as the ad progresses we learn that Nike is surprising Justin with a professional contract—they’re surprising him. But if you Google “signing day,” you’ll see image after image of athletes sitting at a table with a pen and a contract in front of them. Yeah sure sometimes there’s balloons—it’s a great day. But they are treated as professionals because that is what this is—this is a professional contract.

Nike has no idea that what they’re telling us is that they don’t see Justin as a valuable signee. The simple act of turning a professional contract into a gift? tells us that Nike thinks it’s their charitable gesture that creates value. And correct me if I’m wrong but that’s a terrible message to send to disabled people.

But again if you were to really really watch this ad, really pay attention, what you would realize with all these other ads as well is we’re actually…we’re not the intended audience. Everyone else is. They’re simply using us to inspire you. We are nothing more than a brand enhancer.

As a disabled person who is doing this work in the world I now see there are two paths you can take when we find ourselves in these situations. The first path is that you can go the beneficiary route, where we perform gratitude. If we don’t challenge and we do what’s expected, we’re gonna benefit quickly. But it’s never gonna feel quite right to us because we are nothing more than a prop in your stories.

There’s a book called Pathological Altruism; highly recommend it. And there’s actually a really interesting quote in it about how people who hoard animals, their “savior mentality is reinforced because the pet cannot verbally express an opinion of its own.” So “the owner may project whatever interpretation he or she wishes on the pet’s behavior and do so without fear of contradiction.”

And I suppose this is what I’m getting at. Because in that Nike ad, Justin wasn’t mic’d. Nike wasn’t interested in what he had to say. They just wanted his gratitude. And given the build-up and the gesture, how can Justin ask even a logistical question such as how much is the contract for? Or, “Will I lose my eligibility to run at Oregon State if I sign it?” And this is actually what the reality of empathy is, it’s actually more focused on the gesture than the impact. So, empathy.

And I suppose this is really what I’ve come here to talk about today. So, I think a lot of people don’t really understand the history of empathy. The word has only been around for 110 years. It was coined in 1909. And it actually started in like the decade before in Germany. There was a psychologist, his name was Theodor Lipps. And what he saw was that when a person went into a museum and they encountered a great work of art, right, that person they might tug at their collar. They might put their hand on their chests and take a step back, or they might sway.

And what he started to realize was that people were physically moved by works of great human expression. And so he created a word called Einfühlung. And what Einfühlung meant was a person who is physically moved by works of human expression. Anyway, the term caught on. It came to the United States. And the definition shifted. It went from being physically moved by works of great human expression to feeling sympathy, or in the case of disability pity, for a person’s situation or circumstances.

And it’s always sort of struck me as really interesting, right. Because as empathy shifted from inspiration to pity, at the same time disability—this is the last 110 years—disability shifted from pity to inspiration. And I think in all of this we’ve lost the ability to parse out our feelings. I don’t think we know how to separate when we’re feeling pity and when we’re feeling inspiration.

And for me I think this disconnect has led to three outcomes. The first is it reifies class and power structures, right. You always have the empathizer, and then you always have the empathizee, right. The empathizer is cast as the savior, and the empathizee is always the recipient, and those those roles never change.

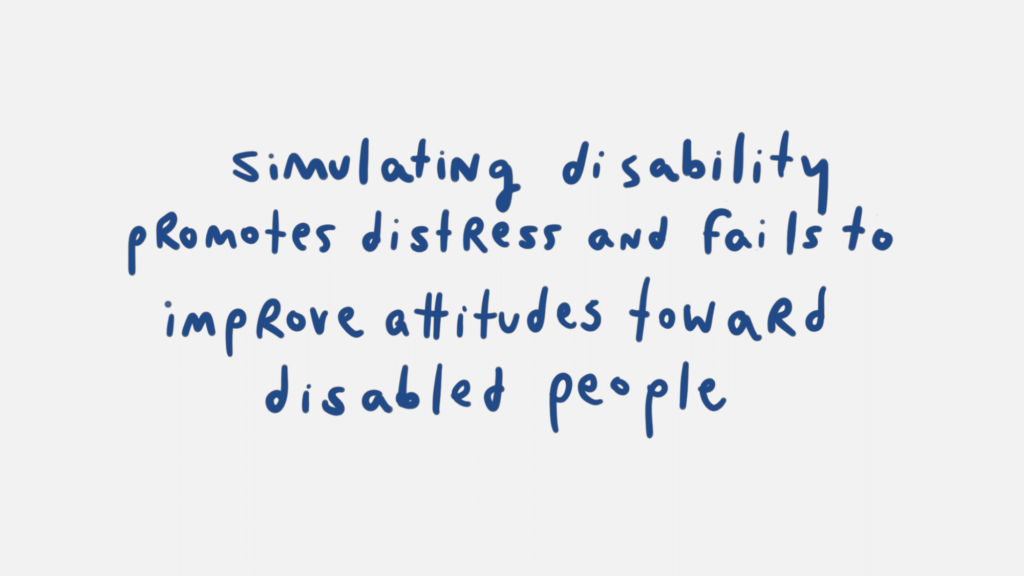

Second, it prescribes emotions. So you know, I think we’ve sort of caught on to this brand of empathy. It sort of feels a certain way. I often say that we’ve convinced ourselves that things that feel a certain way do a certain thing? But they don’t. I would even go so far as to say that things that feel a certain way prevent us from doing a certain thing.

But the third thing is it silences the recipient, right. Because you are expected to be grateful for that which has been done for you.

Anyway, so I said there’s two paths. And what I’m increasingly finding is that I can’t bring myself to go down the beneficiary route. So fortunately, there is a another route which I call the path of mutuality.

So what is mutuality? I define it as a radical act by an individual or group of individuals intended to create space for sustainable participation within a system or institution that benefits from representing or serving us. And what’s that radical act? It’s easy. In lieu of gratitude, we ask questions, right. The only time recipients are valued in this process is when we’re expected be grateful. So instead of being grateful we ask questions. We critique— And I can tell you, from experience after experience, we are usually shown the door.

So this is why I created the WITH Fellowship. So the WITH fellowship is a program within my organization, and what we do is we partner creative disabled people with top design studios and creative spaces. And of course, we are eager as hell to create opportunity. But mostly what we’re trying to do is build an infrastructure that will support those of us who strive for a more equitable and more mutual framework, right. We’re coming together and we’re saying “this is how we want it to be done moving forward.” Because what I’ve learned is that there is no better way for us to honor our disabilities than by committing to the friction of them. We need to be able to interrogate that which feels wholesome.

And it always surprises me when people when people hear of the WITH Fellowship and they say to me, “Oh, you’re talking about codesign,” and I say no. I’m not talking about codesign at all. WITH is the antithesis of codesign.

So what’s the difference? Well in codesign, designers and institutions get to decide when and how they bring in and design with disabled people, marginalized communities, etc., etc. WITH, on the other hand, is disabled people inserting ourselves into that process.

And even if you don’t identify as disabled, your role is absolutely vital in this process. We don’t need your empathy, we need your solidarity. And there’s a really specific way you can provide this. I think it’s time we came up with a new metric.

My organization The Disabled List, we recently announced a new project called Critical Axis where we’re studying disability representation in media by plotting tropes on a matrix. So, if you look at the top right quadrant is filled in, and that’s because that’s what we want brands to strive toward. And basically it’s amplifying and emerging trends in disability.

I do want to sort of take a moment, though, to call out my friends at This Also, which is a brand that helped us bring this web site together, because I feel like they offered…in the process of building this web site they offered a really concrete example of empathy versus solidarity. So I turned to This Also and I said, “Can you help me build this web site?” And like a week later they sent me a sort of contract, a statement of work. And in the contract as I was reading through, I was so excited when I saw that in return for this work they wanted an equitable amount of consulting hours from my organization. And it struck me as so interesting, because it was one of the first times I’ve really seen… This Also wanted more than our gratitude, right. And so I just want to say to you it is okay to want more than just gratitude from us. That’s what we want.

Anyway, our CEO Josh Halstead thought it would be interesting if we treated each of these ads as a minidrama and we looked at them from a storytelling perspective. So we asked our lovely redheaded intern Cameron to dig into a book called The Anatomy of a Story. Later that day, Cameron emails me and he says, “So John the author talks about ‘how when a character is made to be detailed with many character traits, the result is that the audience views that character as superficial.’ ” And I read it a couple times and I was like no. Like, no not at all. And Cameron was like, “Yeah. Way. Like you know, it’s true.” He’s like, “I can prove it.”

So the first thing he did was he showed me a Toyota ad. It was rated the most effective Superbowl ad of 2018. It’s really interesting if you go and look at this ad, there is not a single word spoken by a disabled person. And it relies heavily on tropes. And these were the comments that it received: “I’m not crying you’re crying.” “Gave me chills.” “Wow, Toyota just won an Oscar.” “Man, some brands really know how to advertise.” And, “That inspires me.”

Then he showed me this Maltesers ad which featured a conversation from a disabled person. And she was telling a story, right. And it was a funny story. It received ninety-two formal complaints, and was one of the top ten most complained-about ads in 2017 in the UK. And these were the comments: “I don’t like Maltesers anymore.” “Maltesers ads come across as patronizing.” “Forced diversity.” “Makes me feel deeply uncomfortable.” And, “Blatant exploitation to advance a massive company’s standing.”

And this is the correlation. The more words disabled people speak, the less we are believed. Sometimes I just wanna be like do you have any idea how fucking hard this work is? We’re not believed. This is why we need mutuality. We need to be believed—we need it. Disabled people continually have so many doors shut on us, opportunities taken away because we have the gall to ask questions about something that empathizers feel was generously done for us. I want a new metric, one where we can take pride in the rigor and the substance of disability instead of salivating over generosity and virality. We need to start asking ourselves are our well-meaning efforts causing more harm than good?

So what is interaction? It’s iteration. It’s mutuality. It is the capacity to be open to criticism. It’s collaboration. It is open dialogue. It is the freedom to tell a brand that their narrative doesn’t feel very good, and know that the door is not going to be shut on you forever.

And so I’m here to say yes, it is, this is Interaction Week but it can also be interact with us week. So I hope you’ll come and say hi. Thank you.