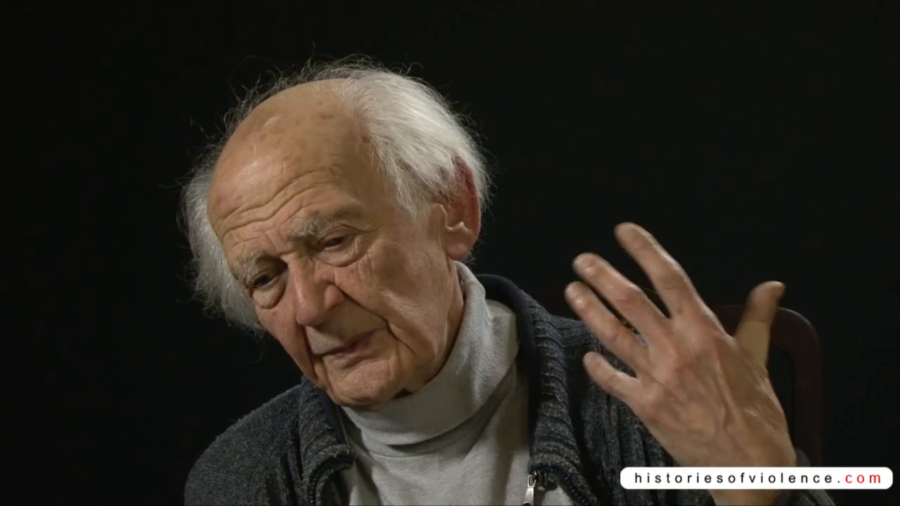

Zygmunt Bauman: Well there are more troubles with modern life, but this one is particularly acute. We feel it very strongly. Namely the obsessive production of redundant people—disposable people. People for whom there is no good room in society, therefore they should be either separated from the rest and put somewhere in an enclosure, or completely disposed of—very often, particularly in our times, just left to their own initiative what to do with themselves.

But why it is so? Why modernity produces redundant people? In pre-modern societies there was no idea of waste; everything was going back into life—recycled, as we would say today. If there were more children coming into the world in a family, then obviously there was room for them, and extra work somewhere in the farmyard, in the field, in the stable. And of course a place around the table. So the idea of being redundant, having no place in society, simply didn’t occur.

But we are living in a different time. We are living in modern time. Modern time has the idea of putting things in order. Modern spirit is about continuing progress, raising the standard of living, increasing the number of products, producing the disposal of people. And the byproduct of all that, or as we would say in contemporary language, collateral victims of this aspect of modernity, are precisely disposable people.

There are two industries typical for modern times which are specializing in producing redundant people. One industry producing disposable people is our obsession with order-building. We remake, we recast, we rehash our order time and again. We are never fully—and rightly so—satisfied with the order of things as it is now and has been created by our previous decisions. And we want to make it better.

Now, the trouble with order-building is that whatever you design, visualize, and try to put in life, in operation a new kind of order, there is always invariably a situation in which some people don’t fit the new kind of order. That’s what changing order, making a new order, is about, about reshuffling the position of people inside and using them better, from whatever point of view. If you have an idea of good society or if you have got the idea of efficient society, greater efficiency, greater productivity—whatever is in your mind—or more coherence, more integration, there’s always a group of people who are disposable, redundant. They can’t be fit into the new order.

The second industry of disposable people is what we call economic progress. Because economic progress means simply that things that shall be done yesterday and before yesterday can be done also today with less investment of effort, with less money, less costs, and less labor employed because of that. And again, if that happens—and it happens day by day—we are constantly under conditions of economic progress.

Now, when it happens, then some people and some ways of gaining living, of earning their living, become redundant. Simply they can’t stand competition with new, more efficient, cheaper ways of doing things.

Two categories of people, people who don’t fit the projected order, and people who are redundant—their skills are no longer usable. Somebody else in the future probably, even robots, will take over the job they have been perform[ing].

Now, they are in two categories of disposable people. Why it is so, particularly in the center of public opinion and politicians’ speeches and so on just today? What is the difference? What’s happened? The production of disposable people started with the beginning of modernity. But, the only part modernizing and therefore producing redundant people were for two centuries almost, Europe. The rest of the planet was pre-modern and therefore they didn’t have redundant people at all.

What Europe did, the uniqueness of this situation of concentration of the modernizing processes in one part of the continent, Euro-Asian continent in Europe, gave this place special privilege which was never to be repeated by anybody else. Namely, Europe could find global solutions to locally-produced problems. Very easy it was to do. One could send the youth, these redundant people to form colonial expeditionary armies, send them there, and then conquer the new lands, and set the local colonial administration there. Again, it was the way to dispose of redundant people who couldn’t be employed in their own country. And so on and so on.

And if you look at European countries, you’ll see that eventually it is impossible to find a family in which some great uncle or great aunt or great-great uncle emigrated to South America, to North America, to Australia, to New Zealand, to Africa, and settled there. And mind you, the present-day Latin America and Northern America is created all by people who left Europe because there was no room for them in their own country. According to some calculations, during the 19th century something about 50 to 60 million of Europeans emigrated to the colonies.

Now 50, 60 million at that time was an enormous amount of people, really. It doesn’t sound very very frightening today, but then it was really movement of nations, so to speak, the wandering of nations around the world.

Now the modern way of life has won, on a planetary scale. More and more countries, particularly all of planet, are now at the modernizing age and they are as eager to modernize as our ancestors in Britain or in France or in Germany or in Russia were. Which means that they also produce redundant people. The production of disposable people is no longer a local trouble, it is a planetary issue. Wherever more efficient ways of producing things are introduced, well, the last part of the local population needs to set off traveling in the search of bread and drinking water. They are all searching wealth, necessarily; they won’t survive. It’s normal survival instinct which pushes them around.

But, they can’t send colonial armies. They can’t conquer other lands. So they are coming to the other country which is already densely populated. It is not an empty room for them to settle. And it looks askance on the coming people, accusing them of all sort of indecent, malicious intentions.

That’s another story, which all should be discussed separately; we don’t have time to do so. How politicians of many [?] are capitalizing on this fear of the locals of the people who were disposable in other countries and came here to settle. They are strangers. They are unknown entities. You never know what they intend to do. You don’t know what they mean when they say something. You don’t know how to decipher, how to unpack, the way they are behaving, the way they are living and so on. It all creates a situation of acute uncertainty. People don’t like it—who likes being in an uncertain situation? So, a fear is emanated from these conditions of uncertainty about their own local condition, created by the influx of people from outside.

So we have a problem. We have a problem of migration. We have a problem—something really shocking. Our minister of home affairs suggests to introduce a new law (I don’t know whether it has been already voted in the parliament or not. It is a fresh matter.), a law which actually allows you to deprive people from their citizenship which they already acquired, on suspicion that they may be a threat to security of the country. Breaking two different things at the same time, two sacrosanct beliefs, principles of what is society and what is civilization.

One, human rights; human rights of the human and citizen—you can’t deprive people of their dignity or their rights which were given to them by the law. That’s one thing which has been broken.

And the other, just punishing people on suspicion. I think there is also a very very longstanding legal principle that a person is considered to be innocent until he, or she, is proved guilty. But here, on suspicion you can strip a person of his right to remain in the country.

Now, this is how far we are— Or “we,” that’s a big question. Who are the “we?” But there it is our representatives, our politicians, how far they are prepared to go, even breaking the principles of our own democracy, of our own liberties, in order to resolve this issue. Of course they can’t resolve it. Of course they can’t resolve it. By the way, there’s a very powerful force which wouldn’t allow them to do [it]. And these are not the voters, these are the businesses. Businesses need cheap labor. Businesses need people who will agree to perform jobs which local, native people spoiled by a hundred years of tradition of trade unions, of working-class struggle against exploitation, they wouldn’t allow themselves to take them up.

So this oppression, it doesn’t hit the first pages of newspapers, particularly the popular newspapers. But it is there, quite a real one. So the introduction of successive strong measures undertaken against immigrants, against strangers which want to settle in this country, they are very often a game of pretend; they’re just making noise around it, which will probably will bring a few more voters into the next general election.

But it is doomed not to be fulfilled, simply because the population of Europe is falling. And according to some calculations, Europe will need actually 30 million more immigrants from other continents in order simply to survive, to protect their own—our own—way of life, which we cherish, and which you wouldn’t like to dispose of.

So we are really in a pretty pickle, so to speak. It is a trouble which doesn’t find an easy solution. Whatever you do, you push it one way or the other, you encounter very powerful and vociferous resistance against doing it. I think that handling the issue of planet-wide migration of people under this condition of overpopulated planet and a planet divided already in sovereign territories where there’s no empty lands left on the map if you look at it… So, all that I think will be one of the major issues, if not the major issue—the most seminal, consequential issue—which people will confront in this 21st century.

Citations

- Chinese Language and Culture Education: Representation, Imagination and Ideology of China in Australian Schools

- The necropolitics of statelessness: coloniality, citizenship, and disposable lives

- Grievable/Disposable lives in the Anthropocene culture: Ecoprecarity, indigeneity and ecological wisdom in Kaala Paani

- Towards a Decolonial Account of Desire: The Cultivation of Desire and Indigenous Women’s Self-Making and Resistance in Early Modern French North America

- Ten Pillars of Neoliberal Fascist Education

- “Underburdened” Communities

- Hospitality and the Ethics of Disposability in Christoph Kuschnig’s Hatch (2012)

- Childhoods in More Just Worlds: An International Handbook

- ‘Sacrifice zone’: The environment–territory–place of disposable lives

- Literature with A White Helmet: The Textual-Corporeality of Being, Becoming, and Representing Refugees

- Hospitality and the Ethics of Disposability in Christoph Kuschnig’s Hatch

- Why do University Students in the UK Buy Assignments from Essay Mills?