[This presentation was posted in three pieces. Section markers appear at the breaks as there were unfortunately brief gaps between them.]

Makani Themba: Hey, what’s up? So I want us to play together… I’ve been thinking a lot about the black future. One, because I want to have one. Personally, I would like a black future. Because I want a future. And then I was thinking about just how many folks don’t actually put black and the future together. And I’ve been thinking a lot about the ways in which we talk, even those of us who are progressive and political about the prospect of the future. I’m probably one of the older people in the room, and one of the things that a lot of us each other is the struggle continues. As if it will be going on for ever and ever, and ever.

And so I decided I wanted to stop thinking like that. So part of my meditation around the black future has been around who are the people who’ve been sort of playing with the idea of the black future as fun? As free? As liberated?

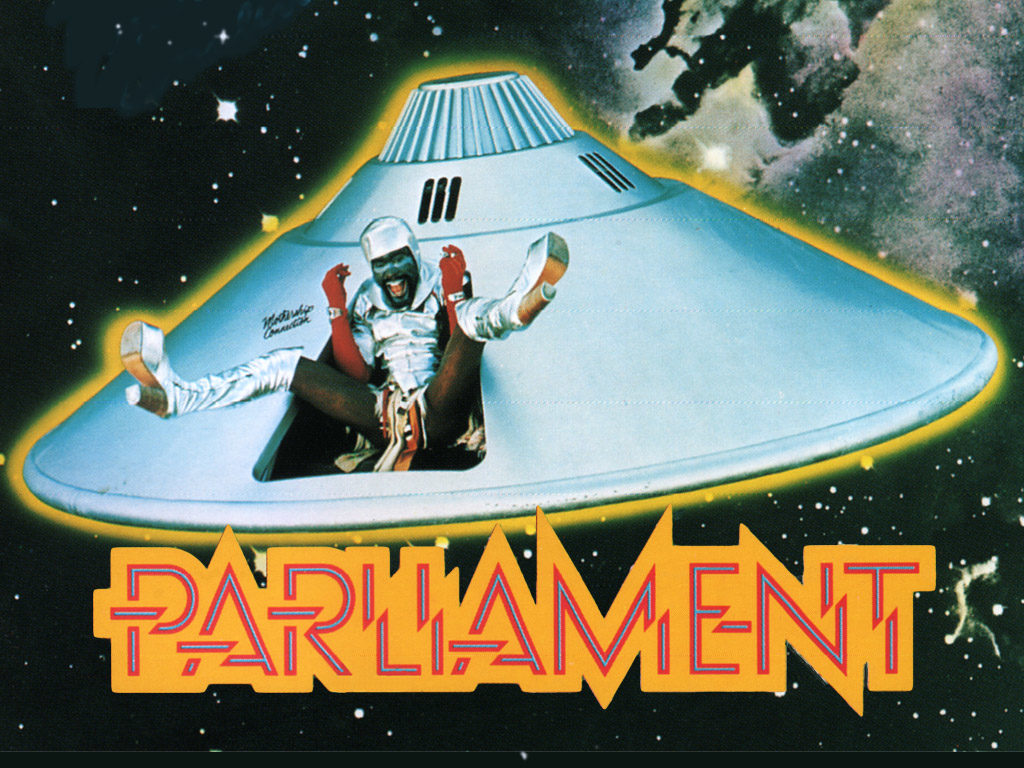

So I started with my man George Clinton from back in the day, because he definitely has been having fun and not limited by the notion of black life and black struggle forever and ever. He definitely took the headrag off and came out in a different way. And there was a couple other people.

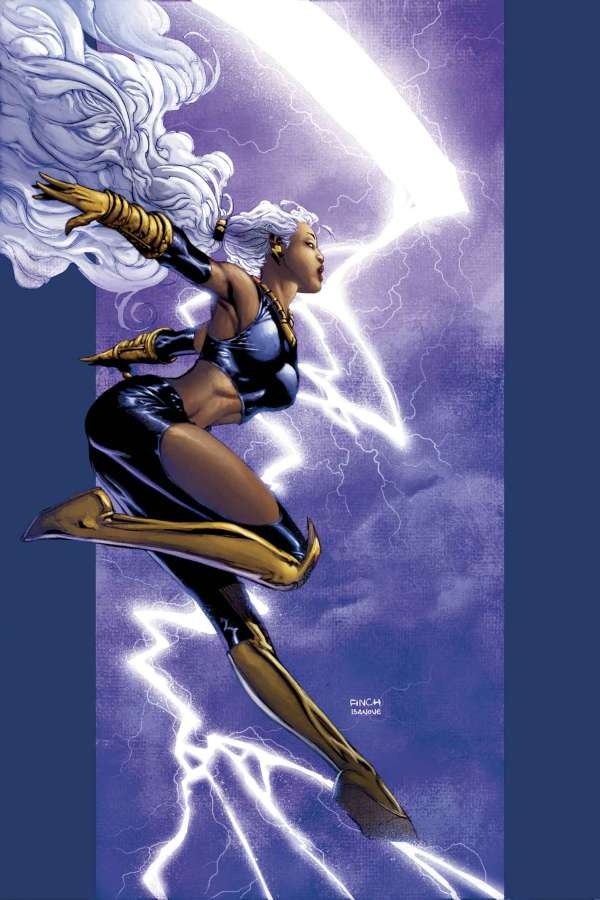

Who knows who that is? You all know who that is. That’s me, right? [Several audience members: “Storm.”] Right. And Storm is about a vision of a kind of a future, right? Who knows the story of Storm? She’s what? What is the negative term they call a mutant? Someone with hyper skills that’s scary, and in many ways a metaphor for so much. And I love Storm, not only because before I cut my hair we had the same hair. And it’s interesting, and many of you guys who are X‑Men fans kinda know the sort of parable that Stan Lee was drawing from, right? He had Professor X as Martin Luther King, right. He had Magneto as Malcolm X. And he was trying to tell this story about alienation and what the future can look like, and this whole struggle.

And what I loved about X‑Men was that he didn’t actually— If you ignore the movies. The movies aren’t really the comic books. The comic books are much better. People know, y’all know. Because y’all my people, you know about comic books. What I always thought was interesting about X‑Men growing up was the idea that unlike the way you grew up learning about the two struggles, they weren’t pitted against each other. So here’s this white man who had kind of figure it out. These are two sides of the same coin, and that’s about love. Mutant love, black love, black people as mutants, whatever. Because there’s ways in which the way this society works, many of us feel like mutants. We feel different, we feel special.

And in some ways we make our specialness a superpower and not the thing that drags us down. And I always think that this is also a powerful image for me, about the black future and the idea of us sort of overcoming and being there, and also running stuff. Because the X‑Men movie they’ll never make is the fact that actually Storm became the leader of the X‑Men fairly early on. And that probably won’t happen, but maybe, maybe. Maybe somebody will make that movie. Maybe one of y’all.

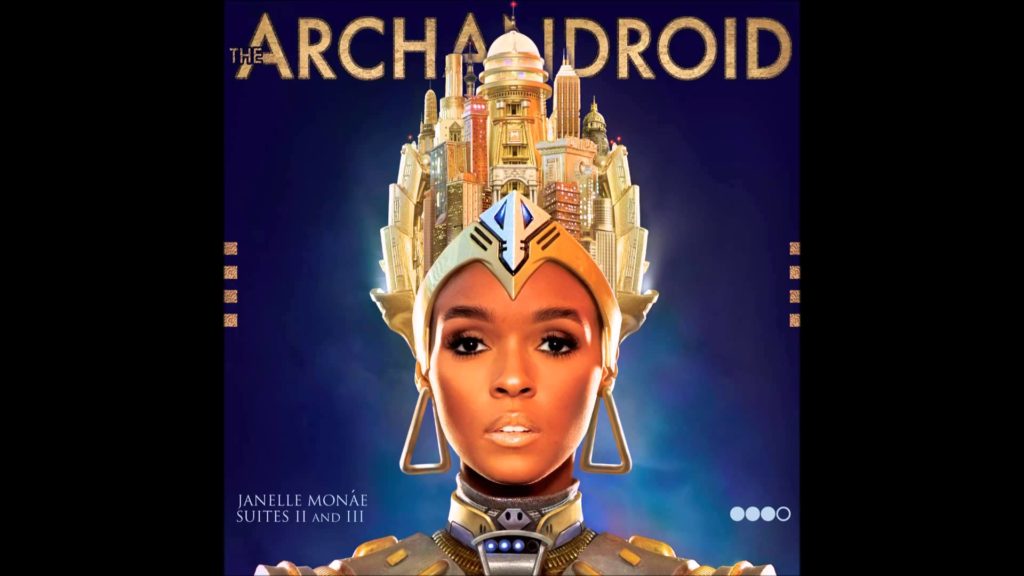

So, you know who this is, right? Janelle Monáe. She also plays with this idea of a black future. The interesting thing, I think, about her aesthetic and her work is that oftentimes people die. I don’t know if people are familiar with her videos, but it has a lot people just dropping dead as the black future, which I find is really interesting. And in many ways it’s sort of like the sort of funk aesthetic in terms of the look, but it’s very sad. And it says many ways about how people feel about hope. So the difference maybe about how folks felt in the 70s about the idea of the black future and maybe how people feel about it now. And I find that sort of an interesting piece.

Now where’s this from? Y’all remember this, right? What movie is this?

Audience 1: That’s from The Matrix, isn’t it?

Themba: This is from The Matrix, that’s right. And despite the star, this movie was really about the black future. And what was the black future like in The Matrix?

Audience 2: Underground. Rough.

Themba: Underground. Hunted. It was hard. [To audience:] Say it again?

Audience 3: Lustful.

Themba: It was definitely lustful, that’s true. People were kinda sweaty and gettin’ at it on a fairly regular basis. That’s true, I forgot about that. That’s true. [laughs] And it’s okay that you remember that. We love you for that. You can’t have a black future without black lust and black love. That’s important.

But what’s interesting about this imagery, too, was that— Interestingly enough for me, it’s one of the few mainstream Hollywood box office movies that showed black people in love with each other. Which is another sort of sense of the black future. And I’m not saying that everybody black has to be in love with somebody black. That’s not what I’m saying. But there’s ways in which in the imagery, and the way the future gets presented, there’s usually just one black person who survives, right? And that’s only when black people aren’t radioactive. Because black people together, it almost seems like there’s a law against that, right? And what’s interesting about The Matrix is that you had a number of couples, a number of people who were really engaged and deeply committed to each other as part of the future.

And the other thing that’s interesting to me about the way black future is presented is that there’s always elements of the past, right? That there’s ways in which it’s hard to imagine. So you have the mothership, right, which is a story about the black future. And that is people are waiting for the mothership to come back, all the original people…you know, we really aren’t from this planet. All the [Silui?] Africans will be levitated up into the mothership and go back to the beautiful place where we came from. That’s one story about the black future, which some people are—I know people waiting outside, for the mothership. Some of them are in the room.

Audience 4: And that’s real.

Themba: Right? It’s real, right?

And there’s also a way in which this whole aesthetic is kind of pimpalicious, right? It’s like kind of like pimp…spaceship combined. And I love that. Because it’s like the mothership is like a Cadillac that’s like extra… And this imagery is just like— I mean, I’m from Harlem. And you actually saw people—you know, I grew up in the ’70s—who actually walked around dressed like this in real life, just at the grocery store getting their Zig Zags and stuff. So…the people who know what that is…

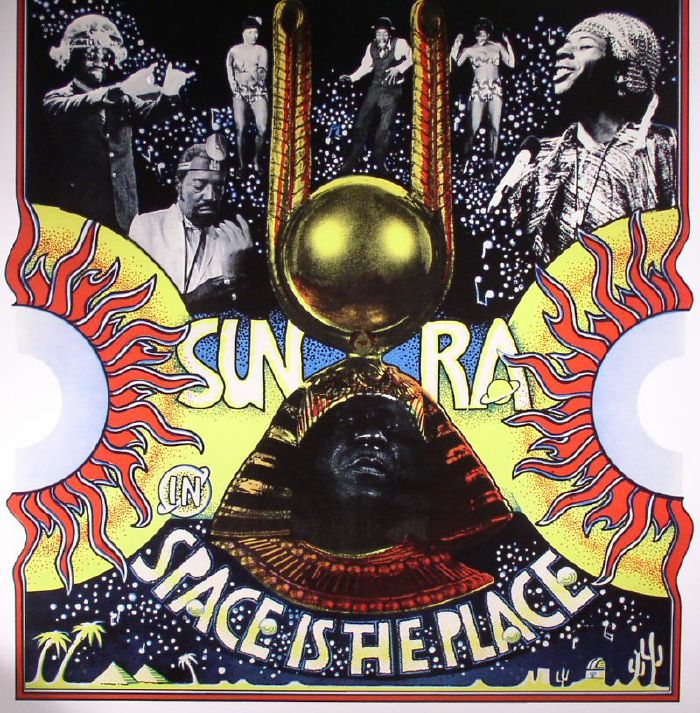

…interesting, too, is that part of what the vision of black future in some ways is about, and I think Sun Ra—who I think is next, yes—probably demonstrated that more than anybody else is this idea that part of what the future is is a going back.

That there’s something that we lost, there’s something that we’re trying to regain. Some of that is about Africa, some of that is about more than that. Some of it’s about kind of a spirit and kind of an energy and kind of a joy that we need to regain. But I always find interesting about picture of the black future is that they almost always have some kind of Egyptian thing happening. They almost always have some kind of West African imagery. Like even The Matrix thing. The Matrix imagery was really African, right? The music, even the sweating. It felt like all your imagery of what you’ve been brought up to think about what Africa is in the imagination. And there’s a way in which that stuff comes together.

So let me just get a little academic for like two slides, and then I’m going to read you a children’s story. And then we’re going to talk.

So one of the things that we talk a lot about when we talk about communications about race and communications about blackness, in many ways, which is caught up in this, is that a lot of times when people talk about the imagery they get caught at the level of imagery. Like, okay this is this image; this image is racist, or this image is great. And we’re not necessarily looking at the history and the context that roots the imagery. Because how we understand a thing has everything to do with how we’re socialized and how we’re educated to believe what the thing means.

So in every idea, in every moment, there are layers. So you have the thing that you’re looking at, you have the context in the way you’re looking at it. So that picture from The Matrix would look one way to us now, and another way to us in the 50s. Because you had people who would just be like…who would have a fight with you if you called them black. That would be something they would want to beat you up over. But that doesn’t happen now. Hopefully. Maybe somewhere, but not many places I know. So context changes things.

And then related to that, the next layer is what do we believe? What’s the history? How do we understand it? What does it say about what we believe about who we are, what the aesthetic is, what’s important?

And all of that, at the foundations are the power relations. Who gets to determine it? So we go to school. Then this takes me to the next slide.

So, we go to school and we learn these things. We learn things about…you know, that color is what race is. As if that’s what race is, right? Or that blackness is all about pigmentation, as opposed to it being socially constructed. I have two brothers who look white. When I say “look white” I don’t mean light-skinned. I mean they look white. They have completely straight hair. No melanin. And there’s no way you’d know unless they revealed themselves. One of my brothers is always walking about like that CB4 line, “I’m black y’all. I’m black y’all.”

And I have another brother who is actually… My brother who is like with the sign, basically, is forty. I have a brother who’s in his twenties, who’s passing. He’s passing. Some people don’t even know what that means. It’s like I’m so old, right? Basically, he operates as a white man in the world. And he’s in his twenties, and you’d think a person in his twenties would feel freer to construct himself, maybe even between races. But he basically operates as a white person, and we send him a communiqué across the lines. His wife knows that he has black family, but she’s never met us. He has like escaped over the edge. And it’s so interesting to me. It’s an interesting thing. We have different mothers, obviously, but the same father.

And what’s so interesting to me about watching my two brothers construct themselves and how they operate and how they live is that among other things it says race is a social construction. You can say it’s about blood. You can say it’s about this. So this idea of people being colorblind, it’s like what does that really mean?

And then they think well, if you shift it and if we move out of that framework, what we’re really talking about is… You know, the political notion for us is more about—it’s really about being privilege-blind. Because there isn’t anybody who doesn’t notice who people are. Anyone who says to me, “I don’t see race,” they are lying. They’re lying. They will be the first person to be like…well, who robbed the store? “Well you know…the person was about 6’3”, he was black,” right?

But there are other ways in which these things are constructed. We talk about historically black colleges, universities, we never say “historically white.” You never do, even though they are.

And if we did, how would that shift the story? If you said, “I went to Harvard, a historically white university,” how would that change it, and what would that mean about what Harvard would have to do to shift and change? To be a historically inclusive university.

But more importantly about how these things are structured and what gets embedded in our psyche about the black future and about black life and about black possibility has a lot to do with how we understand history. And a big part of that is about the fact that we are taught that history is essentially a series of wars. And that the people who win are good people and the people who lose are bad people. No matter what they do. Unless it’s the Holocaust. I think that’s probably one of the few examples of where people were victimized where folks can step back and say, “Okay, you know what? That was bad no matter what.”

But slavery, there’s still a debate on whether that was good or bad. Which is kinda interesting, right? In fact, we don’t even refer to the people who were slaves…they’re not people. They’re just slaves. They’re not even human beings. We don’t talk about them as enslaved human beings, we talk them as just slaves. Which is different, right?

And even the way we understand the way history happens in the US and the whole conquering of the indigenous people is just— The fact that we learn history from East to West instead of West to East has everything to do with that. So those frames become really embedded. And so the idea of sort of imagining ourselves free is hard, because one, who’s worthy of being free? I mean you know, these people came and they had better guns… That’s the story, right? They had better guns and they were smarter. And so that’s how you know whether people are smart or not, because they can kill you, right?

That’s not barbaric, that’s—which I would think would be barbaric and awful, right? That that’s how you would get your wealth, that you killed a whole bunch of people. But no, that’s considered heroic. That’s how we learn it. Manifest destiny, all these other really strange ideas that are really just inhuman and violent and awful. And so there’s only one way you can incorporate and internalize that in your life. If you accept that to be logical, then the only thing you can accept is that the people who it’s done to aren’t human. And so then that makes the idea of the black future hard to hold. Because who’s worthy or deserving? They can’t be the people who just…let themselves be enslaved. How could that be?

And you don’t even learn about rebellion in school. Most of the stuff you learned about all that, somebody handed you a book, or you went to some black history thing, or some cool person in dreads steered you the right way. They’re just like your little guardian like, “You know what? I’m going to wake you up, my brother, my sister.” And you end up in the meeting and you’re like, “Oh my God, I didn’t know this!” Someone hands you that book.

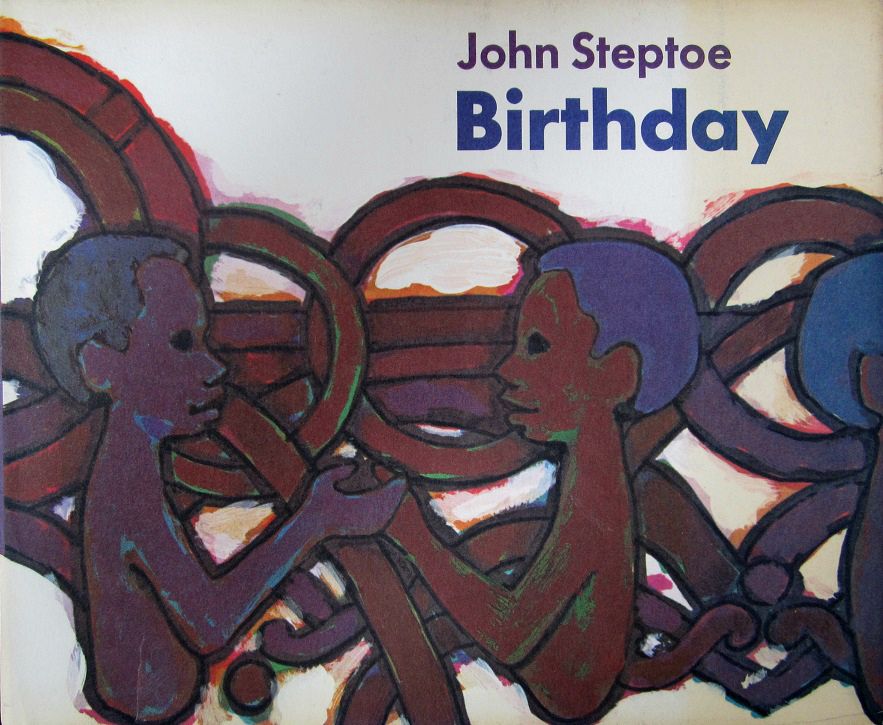

John Steptoe, Birthday; image: Pitt Special Collections

But the thing that to me is really interesting, and I put this up so you guys can see… How many of you have seen this children’s book before? Have you seen this before? Now, what’s interesting to me about this book is that the brother who wrote this book wrote a whole lot of children’s books, most of which are very famous. This is the only unfamous one out of the many—he wrote Willie’s Not The Hugging Kind, which is a very famous book on Reading Rainbow. This book is never on Reading Rainbow.

…started his career doing children’s books and he does the art as well. And one of the reasons why I fell in love with this book when I first saw it was because this is a children’s book about the black future. And I’m going to read some from it because I just love it so. And I can do this without my glasses, that’s why I had to check to check to make sure. The print is big enough.

So this book, I said it’s called Birthday, and it’s about a young man who turns eight on this day. And so I’ll just say that and then I’ll read an excerpt and then I’ll show you a few pictures. And then I’m going to shut down so we can talk.

Today is going to be the best day of my life, and I’m going to have the most fun I’ve ever had. Today is special and I’m special, too, because I was the first-born in our new place. The first child of a whole thing. My name is Javaka and today is my eighth birthday.

We live right outside the brand new town of Yoruba. My Daddy and his friends have farms around it. Yoruba is the name of a nation of people in Africa, and my Daddy and his friends decided to name our place after it.

My Daddy always tells me about the times before we came here to live and the old America, where him and my Mamma used to live at. He says the people there didn’t treat him like a man ’cause he was Black. That seemed stupid to me ’cause my Daddy is the strongest and smartest man alive.

Him and his friends couldn’t live there no more ’cause if he didn’t fight to leave, his life would be no good. When I grow up, I’m going to be strong like my Daddy. I’m almost grown now, ’cause today I’m eight years old!

John Steptoe, Birthday

And so the whole idea of this book, and this is some of it, is that this is about a whole new nation that was founded. People came together—so this is post-struggle. This is after the struggle is done. Which is why it ain’t on Reading Rainbow, I guess.

And basically the story of this new nation is told through the eyes of this young man who’s so excited. He’s the first child free child, I guess in the history of the universe. He’s the first black free child. So this is all about their town and the fact that they have this huge celebration to celebrate his birthday.

And one of the things I love about this and Sun Ra and other imagery is that there’s so few glances that we have of the future. But what we know about the science of strategic communications is that in order for people to understand and believe and engage in the work, they have to actually believe that what you’re doing is possible.

And so the idea of creating art, creating imagery, creating words, that help people imagine themselves free is the most important thing that we can do to help [shape?] this work. And then a lot of times when we think about the work, we use the word “struggle,” and we’re trying to engage people to struggle with us as opposed to be free. You know what I’m saying? And what I’m hoping we can begin to do is step back from that.

I was at a meeting in Oakland at Marcus Books, which is a sort of hangout around—it’s like a blackness-central spot in Oakland—on Martin Luther King. So you know it’s like a black bookstore on Martin Luther King. That’s like, as black as you can get, right? And the conversation was called “Redefining Black Power”, so it was super black. And there was these young men, and they had berets on. So they were extra black. They had black t‑shirts, they were ready. And you know, they stood like this [stands at attention with arms behind her back]. They were ready and they were all in their twenties and they were in the stance, because they had seen the movies with the Black Panthers and everything.

And I loved them, and I loved the energy, you know. And my partner’s someone who’s a leader of the reparations movement. So we were just in this extra black space, right. And one of the young men got up and he started talking, and he was like, “You know what? What y’all need to understand is you have to be ready to die! You have to be ready to die for the struggle. If you ain’t ready to die, then we don’t have nothing to do with you.”

And I was thinking you know, I remember feeling like that. I do. But I do get to the point now where I feel like I’d like to have a moment where you know what, if someone wanted to bring me a pound cake…they could do that. They don’t have to die. If they wanted to like, you know, put some chairs up, sign some people up, make a few phone calls, they could do that, too. And if they wanted to ease up to dying, that’s fine. But you know, they don’t have to start off with that level of commitment, right?

And so part of what I’m hoping we can start to think about when we think about black future is black future as fun. Black future as sexy, yeah. I’m all about that, you know? Black love is to be in black future, right. It should be about music, it should be about all of those wonderful things. And that we work and create and we think about our frames as something that invites people to step into a future where we thrive and that we can help people actually imagine black people thriving, black people getting along, right? Just having fun.

So I want to open up for questions, but before we do this, I just wanted to play a song and let that be the last thing I say, if that’s okay. Just because it’s fun to do that, right, and see how that works out. This’ll be my East Coast contribution, since I talked about Oakland.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WIoNBknkUV4

Further Reference

A blog post about this presentation at the DS4SI site.