Michael Platt: It’s wonderful to be here in Davos sharing our commitment to improving the state of the world. And the recipe is really I think quite simple. All you’ve got to do is grow the economy, increase participation in that economy, within a rapidly-changing world, with increasing automation and technology, on a planet that’s straining to meet our resource needs. Piece of cake, right?

Well I’ve heard a lot of optimism over the past couple of days that we can do this using our human powers. We can of course use our innovative capacities. Employ a little self control and delayed gratification. And of course, increase our compassion, our connectedness to others.

So, how are we going to do this? This is a big challenge. How do we unlock this potential? Well it turns out that brain science may provide a key to unlocking this potential. So over the last ten to fifteen years, the new science of neuroeconomics has begun to provide some compelling answers about how the human brain makes decisions. And this field basically marries contemporary cutting-edge techniques in neuroscience to the mathematical formalisms of economics, and to psychology. And I’m sure you’ve read a lot about this in the media. There’s really been an explosion of findings over the last ten years. And you’ve probably wondered yourself, how do you separate the fact from fiction, the hope from the hype?

Well, I’ve done the hard work for you. So I’ve sifted through a lot of that material, and I’m going to give you four principles you can take to the bank. I think these are rock-solid, because they have been observed in humans, verified in animals, and tested in many ways, as we’ll get to.

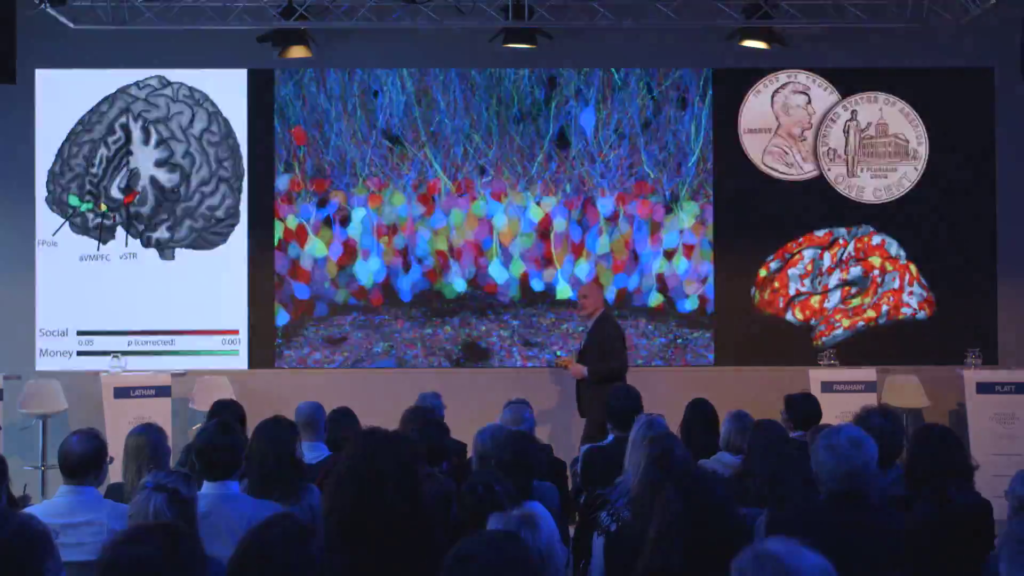

Okay, so the first is we can measure how much you value something by looking inside your brain. You don’t even have to tell us anything about it. So, we can measure your preferences by putting you in an MRI machine and taking snapshots of your brain in action. And we can predict your decisions.

The brain weighs evidence and value, separately, to make a decision. So consider this challenge, which you probably confront many times a day. You’re approaching an intersection, and there’s a traffic signal. And you have to decide whether it’s yellow or red, and what you’re going to do. Are you gonna give it the gas or stop. Okay, that probably depends a lot on whether you’re racing to get your kids to school; this is a problem I face all the time. How about if that traffic light is obscured by fog, as it was last night down in Klosters? It makes the problem more challenging because the information, the evidence, is much noisier.

Turns out the brain has evolved an elegant and it turns out mathematically-optimal way of solving this problem. This was actually written out by Alan Turing when he came up with a method for predicting the locations of Nazi submarines. And all it involves is a little bit of integration. Don’t worry if you don’t remember your high school calculus.

All this means is that you’ve got two buckets in your brain. And each time you get a little bit of evidence saying the light is red, it goes into the red bucket. If you get a little bit of evidence that the light is yellow, it goes into the yellow bucket. Whichever bucket fills up first, wins. That’s the decision that you make. If the evidence is clear, there’s no fog, the buckets fill up quite quickly. You make a quick and correct decision. If the evidence is weak, it’s harder to fill up those buckets. It takes a lot longer. You’re more likely to make an error.

Now, it turns out that value, how much we value one outcome over another, simply acts like a volume knob, okay, that changes how quickly that information flows into either of the buckets. So if you’re feeling like time is of the essence, that yellow bucket’s going to fill up more quickly and then you can press the gas pedal and go through the light.

The third principle. Brain physiology limits the number of options you can usefully consider. It performs all these computations drawing the energy of a low-wattage light bulb. And the way it does this is that every neuron, when it responds to a stimulus, suppresses the activity of its neighbors. That’s great if you’ve only got one thing to consider. How about when you walk into the grocery store and you’re confronted with this? Now you’ve got hundreds or thousands of neurons suppressing each other. Think back to the last slide and those buckets. What you’ve done now is turned down the flow of information to any of those buckets. It’s a lot harder to make a decision in this context. And usually you feel worse about it afterward. The tyranny of choice.

Principal four, probably the most important. Our brains are wired to be social. We can’t help but consider the social context whenever we make any decision. Even the simple decision deciding whether or not to approach a particular person. We’ve performed this experiment. When you ask people whether or not they like this face, you actually get brain activity in areas that respond when you receive rewards like food or water or money. Social rewards activate these areas. And we’ve shown by directly recording the activity of individual neurons in monkeys who are paying for the opportunity to see pictures of attractive monkeys (we can go into to that later), that there are specialized populations of nerve cells, neurons, in these areas that are exclusive to social rewards. So evolution has produced a parallel reward system for social behavior. This is probably why it’s so difficult to disengage from social media. Go get something to eat. (I know this is something my 16 year-old has incredible difficulty doing.)

So, you might imagine there are a lot of applications that might derive from this. We could use neuroscience as a marketing tool. Use this information perhaps to home in on your buy button and press it a little harder. My colleagues at Stanford University, for example, have shown that by scanning the brains of a limited number people in the laboratory, they can predict the effectiveness of microlending campaigns on the Internet. That seems like a good thing. We could also use the same approach to fine-tune our messages to help people make healthy choices. I think another area of potential application is aligning consumers with products. This is sort of precision marketing.

So by understanding something about consumer experience, we can go beyond using demography, where you live, to more effectively deliver products to you that you like. And finally, I think we can also use this information to help align people with their talents and goals. How do you know what you want to do and what you’re going to be good at? We can potentially use neuroscience to either put you on the right path, or help you achieve the right training you need to get there. So my colleagues and I for example have looked at brain responses to risk and uncertainty. Some people can handle uncertainty and some people can’t. If you’re a person who can handle uncertainty, maybe should go work for startup instead of a blue chip company.

In the final few seconds, I want you all now to take a deep breath. It’s a tremendously exciting time to be in neuroscience and think about its potential for transforming society. But there’s a yawning gulf between what we can study non-invasively in the human brain when it’s making decisions, and the actual fundamental cellular processes that make it all happen, that do to computing. And to kind of circle back to Nita’s talk, a lot of the same questions, where we think about the use of drugs that have legitimate purpose in your neuropsychiatric care, such as oxytocin which can be used to improve social function in autism and schizophrenia but may increase trust in people; simple nasal spray. Or stimulants that can be used legitimately to help people with attention deficit focus. These drugs actually act on the same chemicals that underlie our motivation. And of course as Nita brought up, we’ve already accepted as a culture many enhancers that’re going to affect the way we make decision. So, thank you for your attention.