Anastasiia Raina: Thank you so much for inviting me. And something that I would like to talk about is actually coming from my courses and— Although I was supposed to talk about cyborg aesthetics, I decided to actually take a step back and focus on biocentricity in design and pedagogy and the way it affects the way we think about nature and sustainability, and how could we possibly move beyond that, and what are some of the methodologies that I’m utilizing in my classes in order to do that.

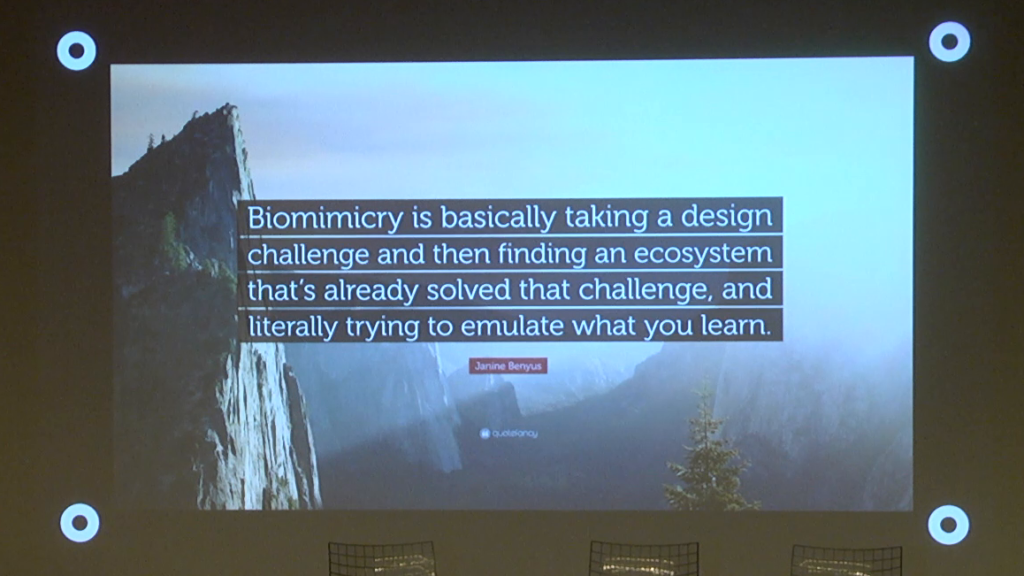

So today, we will examine the historical and philosophical roots of biocentrism, biomimicry, explore the quality of the relationship it presupposes with nature, and question its ecofriendliness. We will introduce emerging alternatives to biomimicry and discuss the challenges it promises.

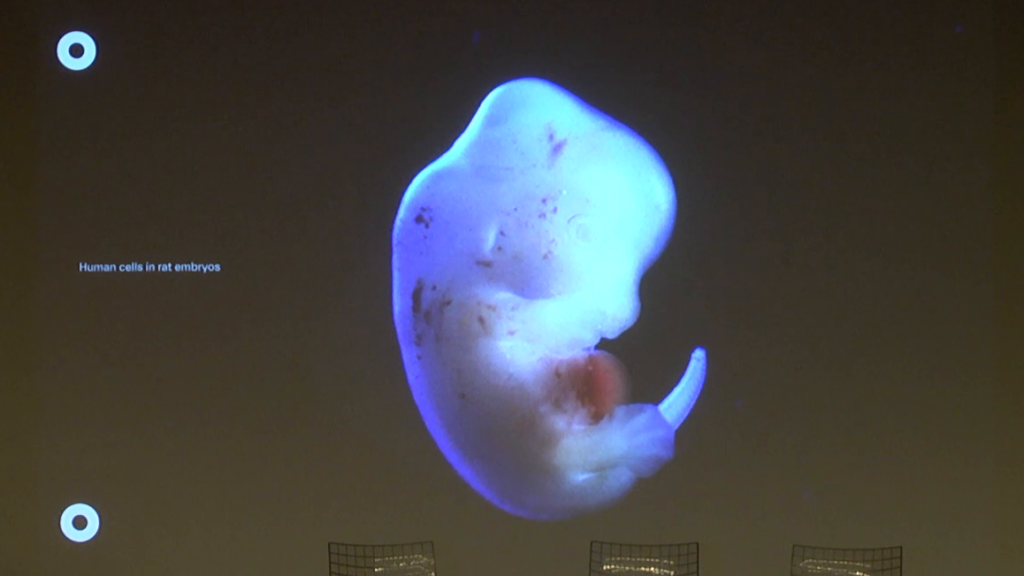

You’re looking at Ambystoma mexicanum, or an axolotl. This salamander is routinely used as a model organism in biological research because of its ability to regenerate limbs, jaws, and even vital organs such as the brain. Scientists hope to use evidence gathered by studying these creatures to eventually endow humans with the ability to regenerate body parts. I came across this wonderful creature a few years back when I was in the process of writing my thesis, and since then I have been interested in the role of nature systems, animals, and their use in art and design.

Few ideals have been as exalted and permeated in the design field as deeply as biocentrism and what we know today as biomimicry.

The formal imitation of nature in the design of objects dates back to 19th century Art Nouveau, notably reemerges in the design philosophy of the Bauhaus, and continues through many works today.

In art and design, biocentrism may draw upon the superficial likeness of nature for decorative, symbolic, and metaphorical effect. And alternatively, biomimicry may study the forms used to accomplish specific goals, inspiring innumerable highly practical human inventions.

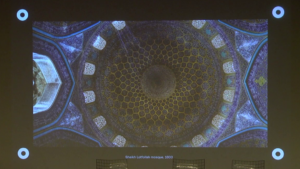

Nature’s influence on design unsurprisingly dates back to antiquity. And organicism, the predecessor to biomimicry and biocentricity in art and design can be traced back to Vitruvius’ writings and Goethe’s work on morphology.

Organicism art is based on the conviction that art should not imitate nature, not with the aim of producing perfectly faithful copies but with the aim of creating the illusion of life, of conferring the qualities of living nature upon the products of man in the hope of effectuating the metamorphosis of dead matter into a living being.*

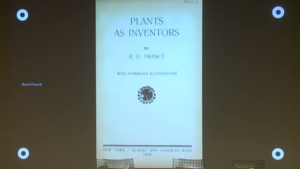

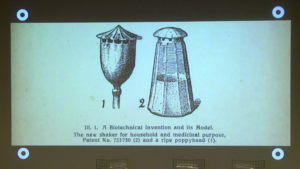

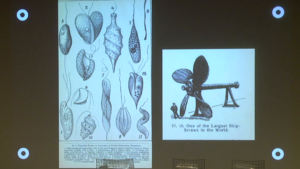

Examination of nature in design gained much momentum in the 19th century, paralleling advances in biology. Notable biologist naturalists of the time including Darwin, Lamarck, and Haeckel detailed how morphological differences served specialized function roles. And 1923 saw the earliest formal conceptualization of biomimicry when Hungarian-born botanist Raoul Francé published a chapter of his book Plants as Inventors in an art journal.

In this text Francé discussed how the idea of Biotechnik, the technological mechanisms of living beings, provide a rich basis for the belief in integrating biological processes in technologies*, and his books are full of illustrations coming from the natural world and they’ve become the source of inspiration for constructivist artists such as El Lissitzky, Wassily Kandinsky, architects and designers, and Bauhaus educators such as László Moholy-Nagy.

The new connection between form and function resonated well beyond its scientific origin, popularized in the Art Nouveau style in France and spread in iterations across Europe. Without a doubt, biomimicry, biocentrism has been a very successful strategy for creating and designing nature-inspired innovations for humanity. Furthermore, for many biomimicry has transcended its practical value, transforming into a quasi-spiritual way of honoring nature.

However, biomimicry may not be the nature as it appears explicitly. Most of the inventions inspired by nature have been used towards the express goal of benefiting humanity and not nature. Through industrialization, producing our nature-inspired novelties are often not made from sustainable materials. Moreover, the methods employed in biomimicry act to reduce, obstruct, and simplify nature into common explodable features, warping the way we think about our relationship to our supposed source of inspiration.

Lastly, rooted in the empirical study of plants and animals, creations employing biomimicry borrow credibly from both biology and nature, appealing to people’s scientific and spiritual sensibilities. Such romanticization of biomimicry leaves it particularly vulnerable to exploitation by marketing powers, through nature-inspired advertising and design contains [mask?] many unsustainable business practices.

So, how do we move beyond biomimicry, avoiding the pitfalls of the past? If biomimicry permits a frame of thinking that allows humans to use nature for its unilateral benefit, though not all bio-inspired innovations exploit nature. In a lot of cases this crude imitation of nature ultimately serves production of objects under the guise of eco-friendliness, sustainability, greening initiatives, afforestation, and other environmental do-goodisms that paradoxically proliferate at the expense of plant life. How do we move beyond biomimicry, and what would more just design innovations look like? And is it possible to collaborate with nature?

The notion of what it means to be human in the 21st century no longer reflects the ideas of humanism. We gradually become aware that the man is not the center of the universe and that we need to expand our understanding of what it means to be human today, and the notion of what constitutes design in the post-human age.*

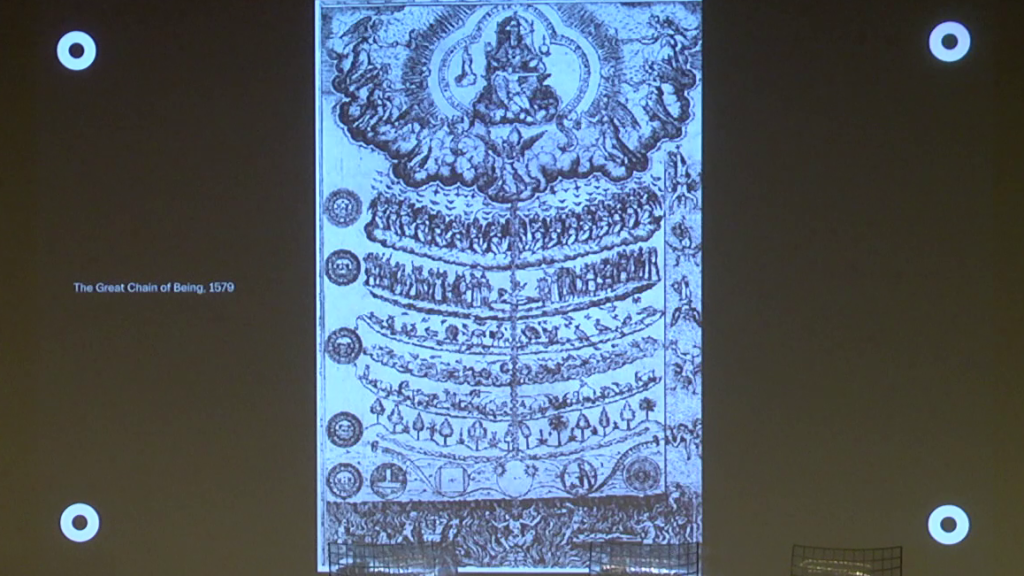

The Great Chain of Being serves as an excellent illustration of the fact that our understanding of the world and design has always been shaped by the act of elevating man over known human realm on a hierarchichal scale.*

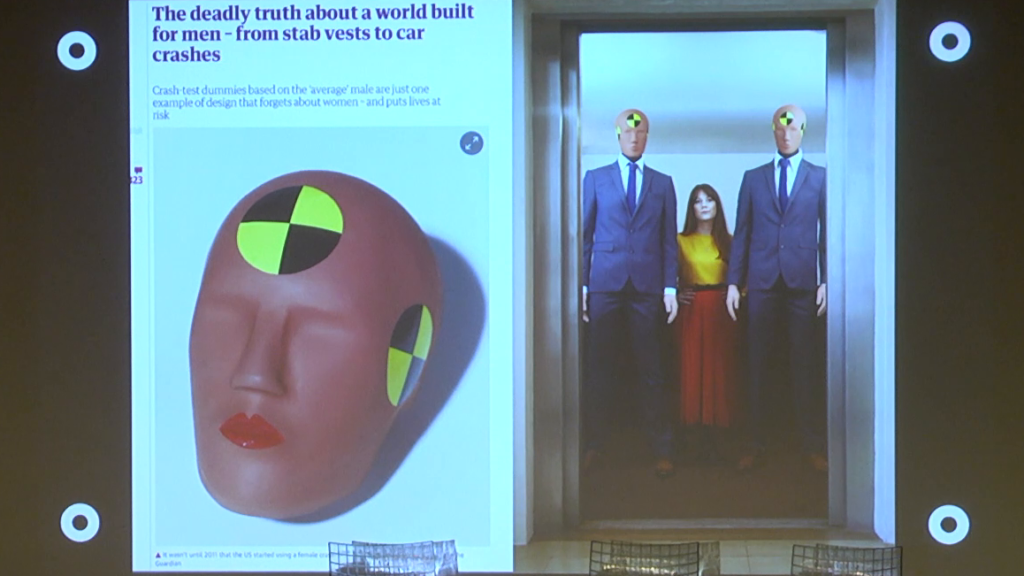

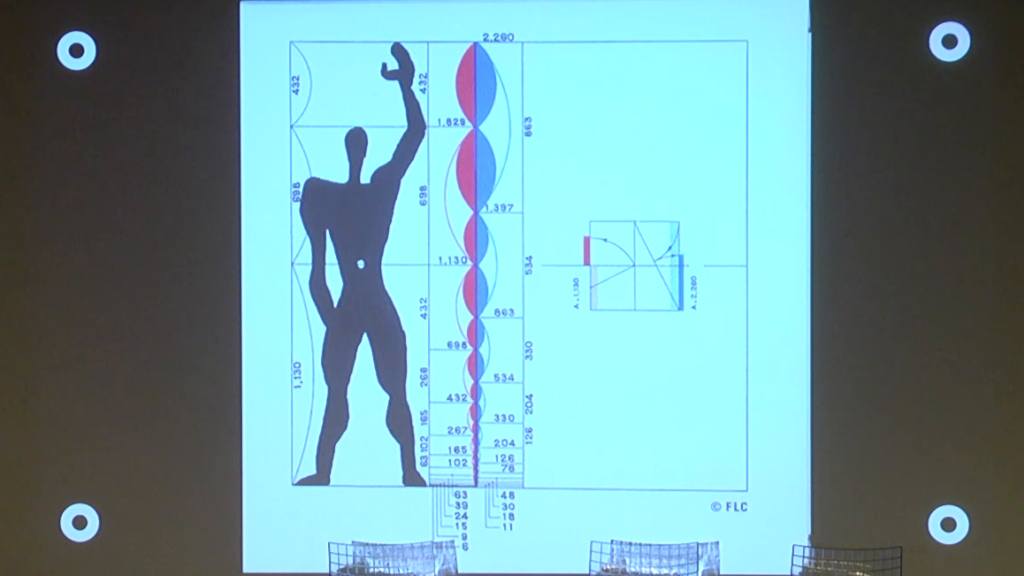

Moving to modernism, we see this idea proliferating in architecture and design in 1930s influential Swiss architect Le Corbusier decided architecture needed a revolution. “Buildings should be designed to fit people,” he declared, and so he set about designing his human scale to do just that.

There was just one minor problem. Le Corbusier’s iconic Modulor Man was in fact well, a man. To be precise, a six foot-tall man, and to be even more precise a six foot British detective with his arm raised to reach the top shelf that I can’t even reach.

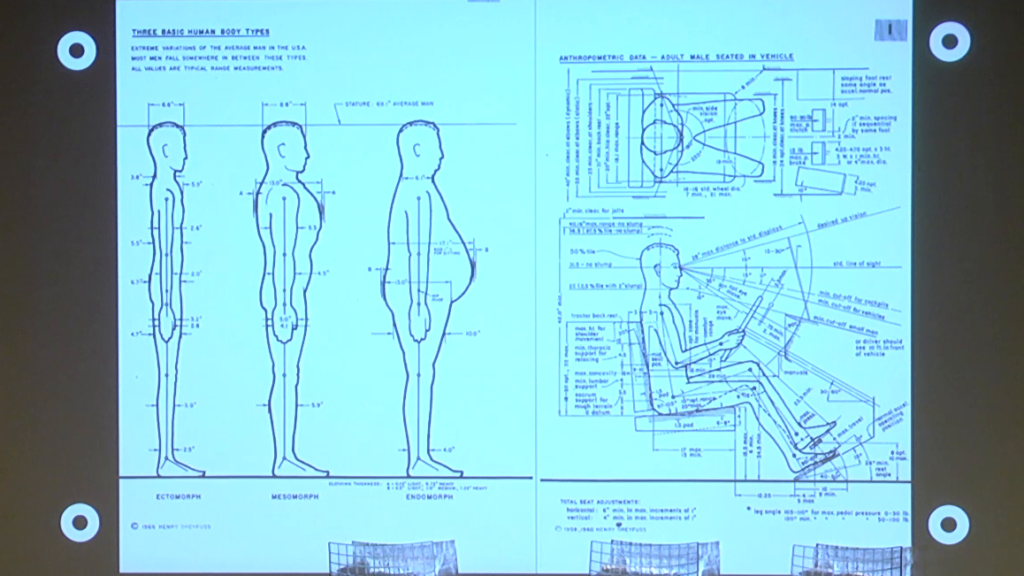

Rather than using body parts as we have been using before as a body measurement, the body itself has become the unit of measurement of the body and standardization of design the rationalization of the body modernism has strived towards.

And as today we see that continues to perpetuate in car design, air conditioning, and further architectural design problems. So an average woman is regarded as an out-of-position driver to reach the pedals and see over the dashboard because women sit too far forward. So they’re likely to be involved in a car crash and less likely to survive the injuries.

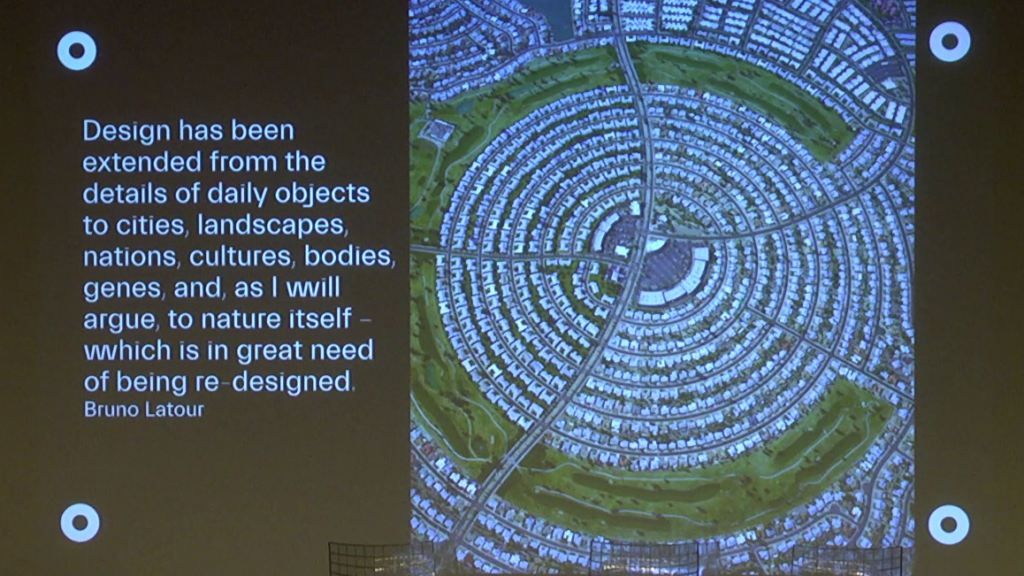

As we can see that every element of our world is being designed, from businesses to government that deploy design thinking, and the planet itself has become an artifact of anthropocentric design that needs to be challenged.

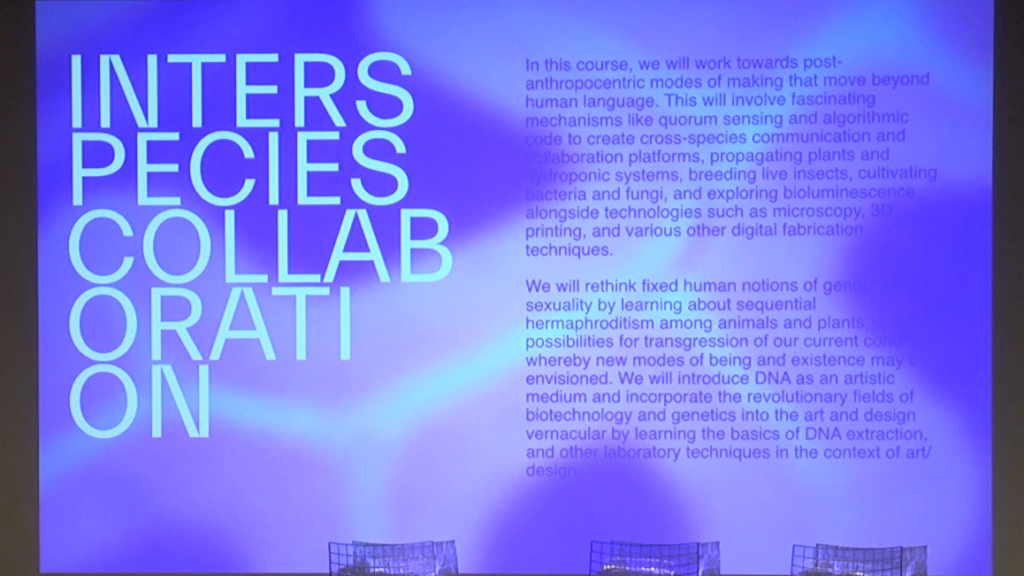

My classroom serves as a place for experimentation beyond commercial design, which has been traditionally true for graphic designers. In my class Design in the Post-Human Age we challenge human-centered design, design thinking, and what it means to be a designer when our client partners, collaborators, are robots, artificial intelligence, and even non-human lifeforms.

So usually when I get students in the classroom they think that this humanism has to do with Ex Machina. But the way I teach it, I believe that humanism at its core is exclusionary and perpetuates binary notions of the human and the other. Posthumanism deconstructs any ontological hierarchy*, to include perspectives of people who continue to struggle to be considered fully human: women, LGBT, post-colonialist persons with disabilities, animals, plants, cyborgs.

We directly engage within RISD’s Nature Lab, which allows us as designers to gain an understanding of scientific approaches, tools that probe the question of what it means to be human today.

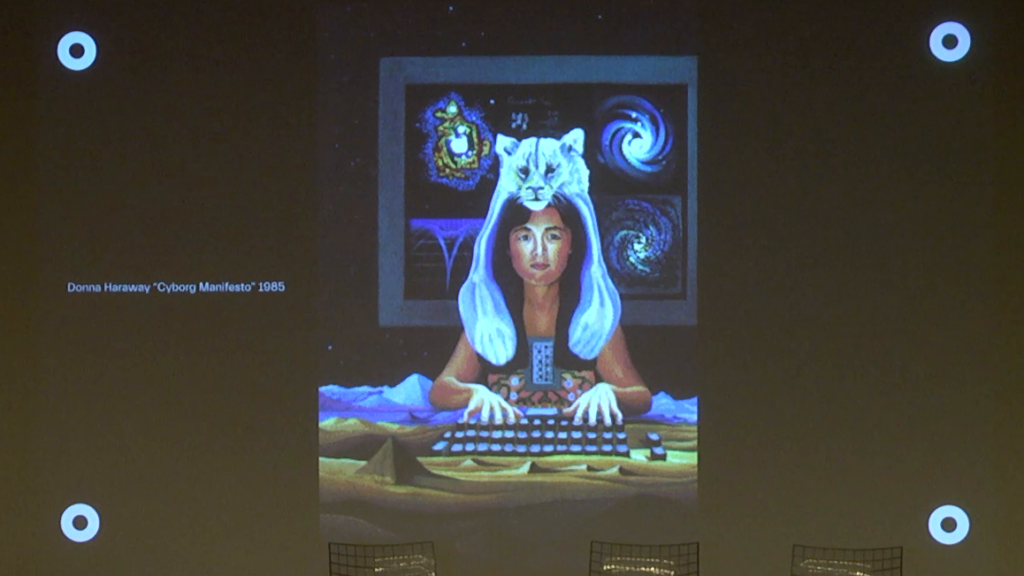

The openness of posthumanism is placed in a hybrid vision of humanity itself, through the cyborg specifically located in the critical reflection of Donna Haraway* and her dismantling of dualisms and boundaries, in particular the boundary between animal, human organism, and machine*.

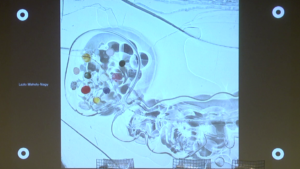

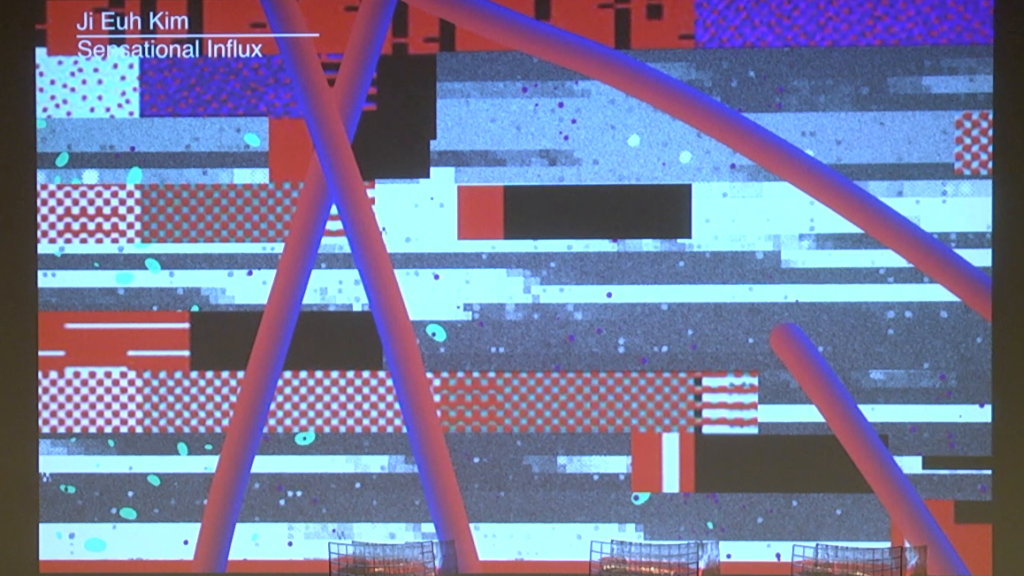

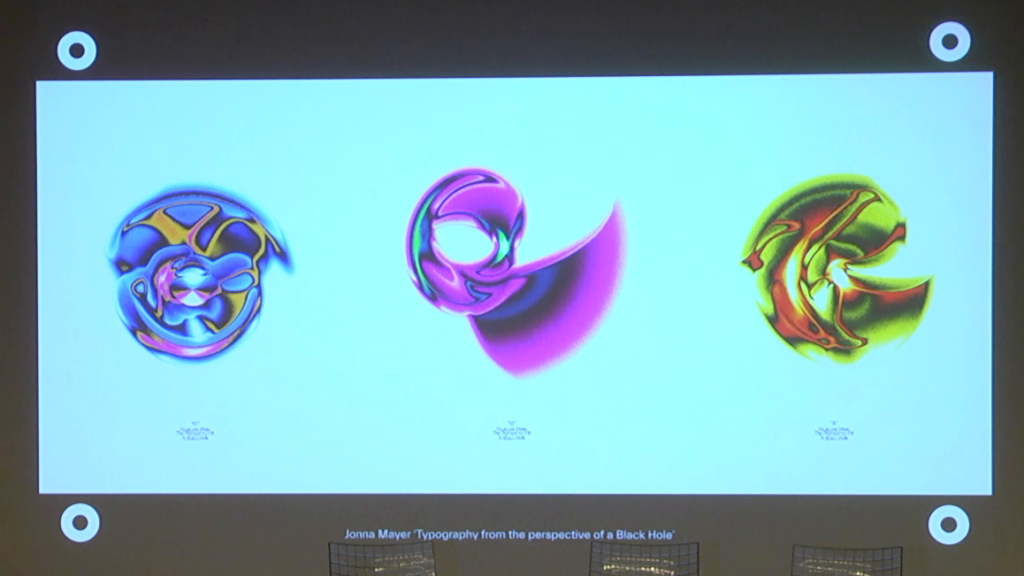

So coming back to the question how do we move beyond biomimicry, avoiding the pitfalls of the past, and is it possible to collaborate with nature? In one of the projects, we explore— Well, I believe that non-human perspectives need to become an active part of design knowledge production. And we may even need to explore worlds beyond human perception such as natural events that occur at a quantum scale. So one of such prompts was based on Thomas Nagel’s What It’s Like to be a Bat, where students were asked to imagine the universe from the perspective of a non-human organism or an algorithm and to embody and document this non-human perspective.

As a follow up students attempted to recreate formal principles of designs from this newly-acquired vantage point. This is typography design from the perspective of a black hole.

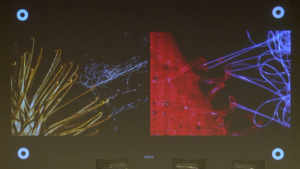

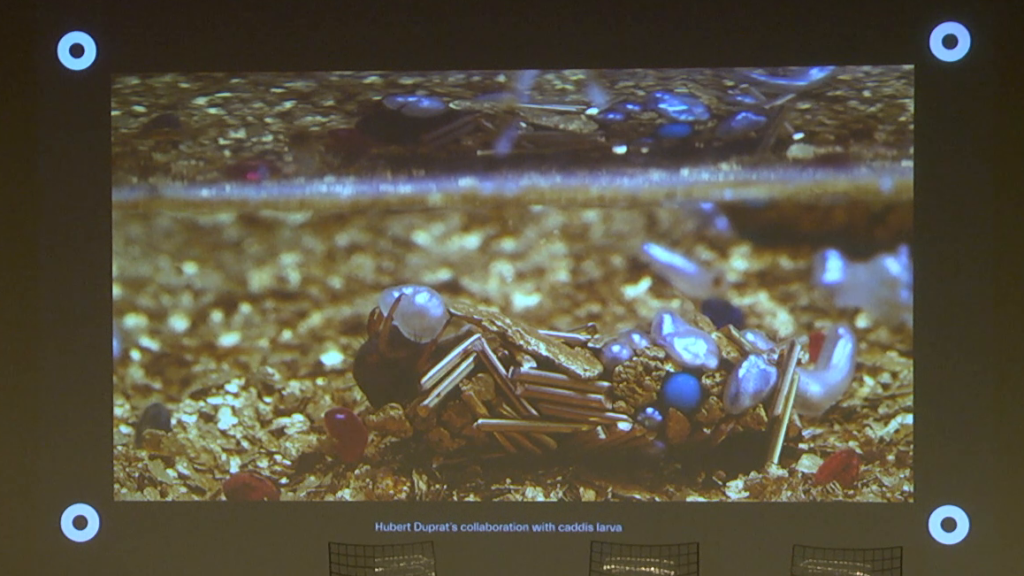

Next, we need to reconceptualize nature as our collaborator, inviting non-human partners to freely participate in creating with us. Collaboration is understood as the act of working together. But what does it mean to collaborate with someone who’s impossible to understand, or whose intention, agenda is not fully known. The crucial part is to learn how these new types of practices can emerge in reciprocal relationships or coproduction between organisms, algorithms, and humans.

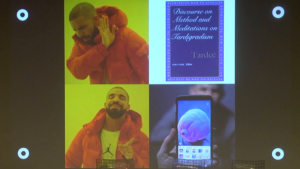

To invite someone into a collaboration is to acknowledge that there is someone. Therefore by imagining and conceptualizing collaborations with other species, humans will be forced to question our self-proclaimed center position in the world, a position that has led to immense destruction of the planet, as manifested by pollution, climate change, and mass extinctions of species.* This is the project that was done by Sarah Park who’s sitting in the third row, where she’s imagining what if a tardigrade made TikToks. She had invented tardigradism, the discourse and method and meditation on what it’s like to be a tardi? who’s the vessel to disseminate the effects of climate change and new modes of survival through the use of meme culture to Gen Z, millennials, and Gen X.

By introducing the term “collaboration” into our work with animals, be it artistic or scientific, we are compelled to acknowledge their agency and personhood, thereby making it much harder and more ethically complex to put animals through the suffering we do today. Instead of using nature systems for our personal and professional gain, we need to invite them to be our intellectual emotional partners in quest for sustainable environment for all of us to thrive within.*

As we develop a more nuanced understanding of the relationships between technology, society, and non-human worlds, we become acutely aware of our all-too-human nature. Our human-centrism and exceptionalism is now juxtaposed with incredible capabilities of other species and algorithmic intelligences. Even when we try to make the leap to embody non-human perspectives, we recognize our inability to escape our human-centrism. I think exactly this failure to embody other perspectives is an important safeguard from false empathy and imposition of our personal understanding on other entities, instead allowing space and possibilities to imagine other types of intelligence that are completely different from our own.* Thank you.

Further Reference

Climate Futures II event page