Rebecca Blumenstein: Good afternoon. Welcome to the biggest climate session at Davos, Averting a Climate Apocalypse. I’m Rebecca Blumentein, Deputy Managing Editor of The New York Times. This has already been a momentous day. And this is a very critical discussion to have now. It’s been a year of prominent headlines on climate. Our job at the Times is to show it, not just to write it. The Australian fires consumed an area larger than the size of the entire state of West Virginia, and smoke from the fires was seen even in Chile. There’s been record heat, droughts, flooding; it has now been officially confirmed that the past decade was the hottest on record.

2020 is an absolutely pivotal year for our world’s climate. Some are even calling it the “year of truth.” Five years after the Paris Accord, governments need to reset their goals, and businesses are finally and quickly talking about setting goals. We’re running out of time to limit warming to 1.5 degrees and to avoid 2 degrees. Scientists say we need to keep warming below 1.5 to avoid the very worst impacts on all of us. And the more we delay, the harder it becomes.

We have top voices from across the world to discuss the urgency of the situation and next steps. But we are going to start with some words from Greta Thunberg, who made headlines around the world last year by saying here at Davos that our house is on fire. I am so honored to welcome her to the stage.

Greta Thunberg: One year ago I came to Davos and told you that our house is on fire. I said I wanted you to panic. I’ve been warned that telling people to panic about the climate crisis is a very dangerous thing to do. But don’t worry, it’s fine. Trust me, I’ve done this before and I can assure you it doesn’t lead to anything.

And for the record, when we children tell you to panic, we’re not telling you to go on like before. We’re not telling you to rely on technologies that don’t even exist today at scale and that science says perhaps never will. We are not telling you to keep talking about reaching “net zero emissions” or “carbon neutrality” by cheating and fiddling around with numbers. We’re not telling you to offset your emissions by just paying someone else to plant trees in places like Africa, while at the same time forests like the Amazon are being slaughtered at an infinitely higher rate. Planting trees is good, of course, but it’s nowhere near enough of what is needed and it cannot replace real mitigation and rewilding nature.

And let’s be clear, we don’t need a “low carbon” economy. We don’t need to lower emissions. Our emissions have to stop, if you are to have a chance to stay below the 1.5 degree target. And until we have the technologies that at scale can put our emissions to minus, then we must forget about net zero, we need real zero. Because distant net zero emission targets will mean absolutely nothing if we just continue to ignore the carbon dioxide budget that applies for today, not distant future dates. If high emissions continued like now, even for a few years, that remaining budget will soon be completely used up.

The fact that the USA is leaving the Paris Accord seemed to outrage and worry everyone. And it should. But the fact that we are all about to fail the commitments you signed up for in the Paris Agreement doesn’t seem to bother the people in power even the least. Any plan or policy of yours that doesn’t include radical emission cuts at the source, starting today, is completely insufficient for meeting the 1.5 or well below 2 degree commitments of the Paris Agreements.

And again, this is not about right or left. We couldn’t care less about your party politics. From a sustainability perspective, the right, the left, as well as the center have all failed. No political ideology or economic structure has been able to tackle the climate and environmental emergency, and create the cohesive and sustainable world. Because that world, in case you haven’t noticed, is currently on fire.

You say children shouldn’t worry. You say, “Just leave this to us. We will fix this. We promise we won’t let you down. Don’t be so pessimistic.” And then…nothing. Silence. Or something worse than silence: empty words and promises which give the impression that sufficient action is being taken.

All the solutions are obviously not available within today’s societies, nor do we have the time to wait for new technological solutions to become available to start drastically reducing our emissions. So of course the transition isn’t going to be easy. It will be hard, and unless we start facing this now, together, with all cards on the table, we won’t be able to solve this in time.

In the days running up to the fiftieth anniversary of the World Economic Forum, I joined a group of climate activists demanding that you, the world’s most powerful and influential business and political leaders, begin to take the action needed. We demand at this year’s World Economic Forum participants from all companies, banks, institutions, and governments immediately hold all investments in fossil fuel exploration and extraction, immediately end all fossil fuel subsidies, and immediately and completely divest from fossil fuels.

We don’t want these things done by 2050, or 2030, or even 2021. We want this done now. It may seem like we are asking for a lot, and you will of course say that we are naïve. But this is just the very minimum amount of effort that is needed to start the rapid sustainable transition. So, either you do this, or you’re going to have to explain to your children why you are giving up on the 1.5 degree target. Giving up without even trying.

Well I’m here to tell you that unlike you, my generation will not give up without a fight. The facts are clear but, they are still too uncomfortable for you to address. You just leave it because you just think it’s too depressing and people will give up. The people will not give up. You are the ones who are giving up.

Last week, I met with Polish coal miners who lost their jobs because their mine was closed, and even they had not given up. On the country, they seemed to understand the fact that we need to change more than you do. I wonder what will you tell your children was the reason to fail and leave them facing a climate chaos that you knowingly brought upon them. That it seemed so bad for the economy that we decided to resign the idea of securing future living conditions without even trying?

Our house is still on fire. Your inaction is fueling the flames by the hour. And we are telling you to act as if you loved your children above all else. Thank you.

Rebecca Blumenstein: Thank you Greta for those stirring and provocative words, and for your leadership on this issue. I am going to start by asking our panelists a number of questions. We also want to open it up to you by the end of the session. And if you could please join us on that wef.cs/vote, we will also get you registered because we like to take a couple polling questions in the middle of the session as well.

Ma Jun, I’d like to start with you. China is by far the largest emitter on Earth. And what would your response be to Greta? What will it take for China to really emerge as a leader on this issue, even probably without the US?

Ma Jun: Yeah, I thank I greatly salute Greta’s efforts because it has helped to vastly increase the public awareness globally. I think the public must play a vital role, you know, if we want to avert a climate crisis. And this is quite evident in China, you know, during this economic development in China. Just like in the West, our fossil fuel consumption has massively increased. From the year 2000 to 2011, just eleven years, our coal consumption has been tripled, burning half of the world’s coal. And the original projection is for that volume to be doubled before we peak by 2014. Thinking about this is not sustainable at all. But Chinese people, our citizens, made their voice heard when Beijing and the surrounding regions suffered from a long stretch of smoggy days, demanding for clean air. Millions of citizens on social media.

And then the government responded to by starting monitoring and disclosed PM2.5 and then rolled out a national clean air action plan. And I’m happy to report, though all this public/private partnership during the past seven years, Beijing’s PM2.5—you know, the fine particles concentration—has dropped from ninety micrograms to forty-two last year. So more blue skies. And during the process, the toughest issues of coal— You know, China’s coal consumption increases have been brought to an abrupt stop. Last seven years, not much increase at all. Stagnated.

But that’s not enough. Our mission has not being accomplished. We’re still burning half of the world’s coal, and we need to do more. But now, at this moment, we’re facing the economic downturn locally, and globally we’re facing a trade war, and also the withdrawal by the US government from the Paris Agreement. All these are not helpful. So, we need to find innovative solutions which tap into the market power which can balance growth and protection. But all this needs people to join their efforts. So with that, I truly salute the efforts to raise public awareness.

Blumenstein: Oliver, you head Allianz, one of the world’s largest insurers, and in September along with the United Nations launched a net-zero alliance, which is basically encouraging managers and some of the biggest funds to be carbon neutral by 2050. And it feels uh, you know, to Greta’s point: why does it take so long? 2050 is fifty years from now?

Oliver Bäte: Yeah, it’s a [indistinct]. Not quite fifty years from now but only certain thirty, thankfully. But it’s still too long. So I fully share the outrage of a 19 year-old daughter who is also asking me the same question every day. We heard part of the answer just now. But I want to be a little bit more optimistic. We have to be between outrage, and optimism. I cannot get up every morning and just be outraged. I have to run a large institution that’s the largest institutional investor in Europe, probably. We have to do something. So we’re trying to connect the optimism and outraged by doing stuff…practically. And financial markets have been very weak in supporting, and investors very weak in supporting, the transition.

So I was personally in Paris five years ago, and I have to admit that I think we had much higher ambitions than what has been achieved. But I would like to point out a simple thing. It’s the first time that business is leading, and governments are behind. In the past it was always governments demanding business to change business models, and then we had to adopt. Today, unfortunately I believe that governments are behind the curve, behind the river. I can only speak for my home country. We always talk about the plans when we would get out of coal, but with discussing dates we’re not discussing action. What we are trying to do is put the real action behind it. Now you can debate the 250, but the reality is we started with 2.4 trillion US dollars committed to go net zero—we had nothing before. Probably by the end of the week we will have more than doubled it. And once we are on the track, we can talk about exhilaration.

But all of this, sorry to say, we need to move from outrage also to science. We need to do practical things to say how do we actually address it? But I also will say without proper support of the governments, particular in the United States, in China, and India—which is also planning to massively increase coal emissions…it will futile. So we’re going to do our job, we’re going to exert the pressure that we can, and we work every day to make it faster. But there’s a limit to what you can do.

Blumenstein: So just to just repeat that, you’re trying to get a doubling of the commitments this week at Davos by—

Bäte: Yes.

Blumenstein: —meeting with various investors around the world

Bäte: Yeah. And the key constituents group—and you can all help—is the sovereign wealth funds. The most amazing thing I found out over the last year, that we can convince very strong asset owners—CalPERS and others that have led the way in the United States, Pension Denmark in Scandinavia is always with us, our colleagues from AXA and others—we are committed. The most amazing thing is that the sovereign wealth funds, often by countries that have huge carbon issues, have not yet signed up. So we need to make sure…you know, the Norwegians need to sign up—they make all their money with fossil… We need to get the Japanese involved. By the way, your Chinese government institution, their pension money can be invested so we could mobilize trillions and trillions more into the right direction. And then I’m very happy to talk about acceleration. But first, they need to commit. And then, we speed up.

Blumenstein: Hindou, you come from Chad, which is first-hand experience in the impact of climate change. And you also serve on the board for the Tropical First Alliance. Can you talk about climate change and how it’s affecting the people in Chad, and really the enthusiasm and willingness for them to play a very big role in what needs to happen.

Hindou Oumarou Ibrahim: Sure. Starting just by what Greta said, our house is burning. She said at the beginning, and the end. So for an indigenous people, when we say the forest is burning it’s not just like a language of expressions. It’s our real home that’s burning. Because indigenous peoples from all over the world—it can be from Chad, from the Amazon, or from Indonesia—we are depending on these forests with our food, our medicine, who’s our pharmacy, our education. So, for indigenous peoples in Chad, especially my community who are pastoralists, cattle herders, are still nomadic. We are not depending on the end of the month. We are depending on the rainfall. And the climate impact, it’s on our environment, our social life. Our environment, when the rain becomes much and much shorter, with a heavy rain which can flood all our crops, or with a drought which can follow and dry up all our food. So that leads to the community to fight among themselves just to get access to these resources that are shrinking.

This is today. This is our reality. When the forest is burning in Australia, in the Amazon, it’s forest that’s disappearing. But in my region in Sahel, it’s people dying. Dying because of the climate change, losing their life, who do not think about the future And that’s also when people talk about 2050 for me I’m like, really? Seriously? By 2050, there’s no solution for this planet. We need it now.

So when they fight, you hear about the migrations which become more and more. They migrate just to get access to the resources. And that’s also what’s happening the last months in Burkina Faso, in Mali, in Nigeria, and going on and on. The people who live in harmony among themselves, which is pastoralists and farmers, now they are fighting. So, the nature that protect us becomes the enemy of the peoples. That’s how we’re experiencing every day. And that changes the social life of men and woman together, and we get more of the sever impacts. So the action I think needs to happen now. And that’s also why the company acting is good. China’s acting, it’s good. But are we acting now? Are we acting for the real peoples? If we are doing it, yes. So, don’t talk about [net-zero] by 2050. Talk about acceleration today. Change your policies. Change your business. Because for us, we are already getting it and adapting.

Let me tell you why very shortly. Because indigenous peoples around all the world, we have the wisdom. We are the most impacted. But we understand nature. We developed the knowledge. We adapt. And we know how to restore those forests that are burning. And look at the news in The Guardian where they are saying the indigenous peoples of Australia, the two old woman protecting their land because they know how to keep the fire away, is the case of all indigenous peoples. A grandmother from Pacific, she knows where to get the crops after a hurricane to feed her family; as my uncle and aunties cattle, when they move they know how to restore the ecosystem. So businesses need us, because we are the future. We are the solution as indigenous peoples. So you need to listen to us, learn from us, and get your business sustainable. You cannot keep your partners, because for us nature is our partner we’re protecting. And for you, you need to protect your business and listen to us. We’ll help you to do that.

Blumenstein: Rajiv, you’re the president of the Rockefeller Foundation and also worked in the Obama administration, where you were known for working with both Democrats and Republicans. Is there any hope for climate not being a partisan issue? As Greta said, she doesn’t really care about politics, but that’s usually how it plays out.

Rajiv J. Shah: I think there absolutely is. I’m so glad that Hindou just gave us that passionate description of how climate change affects people and lives, today, right now, not in the future—not only in the future. And I think that’s perhaps the key to getting out of a political debate about climate change and getting to practical solutions. I’ve had the experience of walking on farms in Ethiopia with famous climate deniers from the United States—Congress. And when they talk to farmers who’re growing food to feed their family, barely getting by, and they recall the past famines in Ethiopia and what that was like, and they hear these farmers say every year it gets hotter, it gets drier; rainfall becomes more erratic, and we face a longer period of food insecurity on a regular and annual basis, you can’t argue with that. And that’s not about the debate. That’s something that is the felt experience of hundreds of millions of people. And in fact, climate change today bears its brunt mostly on the bottom 2 billion people on the planet. And so our commitment to Paris, our commitment to be serious and urgent in taking actions to meet those targets is not just about protecting the future, it is also about protecting today people who rely on climate, environment, and those natural resources to survive and to thrive.

At the Rockefeller Foundation we support 15 million farmers in Africa with improved technology and financing. And we see every day practical solutions that should be free from political debate. We know that there are It’s not future technologies, they’re current. Crops, and access to fertilizer, and access to services that can help farmers move their communities out of food insecurity.

We just a few months ago launched a billion-dollar joint venture with Tata Power in India to bring renewable solar microgrid energy to communities that frankly, the government says they’re connected to electricity…but they’re not; they get a few hours a day and they can’t grow their communities that way. We now with solar technology and improved batteries and storage solutions can provide power at a lower cost, fully-loaded, than any coal plant connected to a grid, connected to extension, into those rural communities.

It’s a fallacy to believe that solving climate change has to trade off with the living standards and improved living aspirations of the world’s 2 billion poorest people. And I think in that space we ought to be able to find really practical bipartisan solutions that can solve both challenges, climate and poverty.

Blumenstein: But could I challenge that a bit? I know backstage we were talking you know, is it a fallacy to expect that people who don’t have electricity yet are going to be able to not rely on fossil fuels? Is there like a little bit of a reality check that we need in terms of how we help those people?

Ma: Yeah, I think those who have must carry their responsibility to those who have not. You know, taking China’s example, you put it quite correct that we’re by far the largest emitter in the world. This is a result of China being the factory of the world. Increasingly we’re manufacturing to meet our rising demand, but in the meantime we’re still manufacturing for many parts of the world. And all those exports carry a lot of embedded carbon and pollution. And in 2007 we launched the Green Choice initiative, where we mapped out the factories’ performance in China and found many of them are major suppliers to those global brands’ day-today consumption. And during the past ten years, many of them started responding. And they started motivating thousands upon thousands to change behavior.

Having said that, there are many businesses which are not doing that. We’re tracking 439 brands, and among them, 300 are not really wanting to even take a look at those violation records. We have 1.5 million, 1.6 million records of violations compiled in our database. But if they compare the lists they can easily identify the problem. But many businesses would not take a look at that.

And more recently you know, the green finance policy in China…we responded to that and developed a dynamic environmental credit rating system. And 6 million factories can give dynamic ratings. And there are so many who claim that they want to go ESG investment. Many are making heavy investments in China. We checked some of the portfolios. They’re not all clean. There’s all this data available. I mean, are you really doing that? Are all these ESG investors—

Blumenstein: So there’s a press release saying they’re ESG [crosstalk] and they’re doing something completely different.

Ma: Yes. Yeah, many of them are not factoring in the so-called “scope 3” carbon emissions, meaning the supply chain supply chain. Supply chain usually accounts for 60, 70, sometimes 80% of the total carbon emissions. If we don’t integrate that into the action, if we don’t distribute that to the factory of the world like China, and of course now to many other developing countries, then the Paris Agreement…we won’t be able to achieve that.

Blumenstein: So just keeping your global headquarters eco-friendly does not do it [indistinct]—

Ma: Yeah, changing the lightbulbs or reducing some business traveling, that’s not enough. Because by far the largest emission is during the manufacturing process. And that dirty work, those heavy duties are still being carried by China now. And some other country’s going to take take it over. But this time, we want to stop the migration of all this pollution. With all these new technologies available, you know China have done so much monitoring. We installed automatic monitoring on tens of thousands of major emitters. Now every hour, if you check our mobile app called Blue Map, you can pull out thousands upon thousands of major factories hourly disclosure data. We visualize by helping people to see whether they’re in red or in blue. And major brands like Apple, like Dell, like Levi’s, Adidas, HMM…I mean, Target, Gap—they started tapping into that. But there are so many more which turned a blind eye because…you know.

So I would hope that the people, especially the younger generation, with all this enthusiasm, pay more attention to the businesses’, you know, actual businesses’ action rather than just a press release.

Blumenstein: Oliver, why is it so hard to reduce fossil fuels and to get business to really comply?

Bäte: We’ve just heard it. We have competing objectives, right. People want to have life [indistinct]. They want to grow. They come from very low living standards. And while we see that in Chad and other peoples of India, people say, “I want electricity and I don’t care whether it’s coming from coal,” and they’re precious. But these are all excuses. I want to pick up on what we’ve just heard.

The financial markets have to play a much bigger role, particular banks also in lending and others, not to give money to supply chains that do not listen. So what we really need is transparency, who’s doing the right thing, rather than greenwashing. And it’s very important that policy makers now make a decision that says “we want to understand what happens in your value change in business.” We are doing it individually. We’re doing it with the asset owner lines. We’re asking the businesses. But it’s ten out of hundreds of trillions. So we need to make this change at scale. So I wish we’d get support—not just this week but others—to really increase it by fifty-fold and not take thirty years to do it but over the next week. Because if there’s no funding for the supply chains, there is no business model that can continue to pollute the world.

Blumenstein: Should companies be required to disclose their carbon emissions? They’re not now.

Bäte: Absolutely. Absolutely. But we have many other things. For example Germany, we’re taxing energy consumption, we’re not taxing carbon footprint. So there’s zero incentive to move out of fossils. So pretty please for all the warriors, let’s do some practical things that we can do. And even if the reforestation was just criticized, in many many countries we are giving tax incentives for exactly the wrong type of forest to be built. Not the ones that are sustainable for drought or for fire and others. We’re actually fast-growing [indistinct]. So there are so many things that we can do tomorrow, but it has to be done.

Blumenstein: Hindou, President Trump just announced a pledge to build a trillion trees, I believe, in a reforestation initiative. Is that gonna help, and could you talk about broadly the role that nature, that the natural world can play in reducing climate?

Ibrahim: Okay well. I will come back to this one. But I just wanted to react. We are having like two [separate words?] here. When we talk about people wanting electricity I’m like, seriously? People who didn’t get food for themselves, who can’t eat three meals a day, are they going to think about having electricity they’re going to have to build for themselves? So I think we need to talk about this inequality between what is technology, what is development, what is the need of the peoples, before we talk about how we can tackle climate change or energy or not. So developed countries need to shift, and right now, from the dirty energy, from coal or whatever, to the clean energy. But not for developing countries, because developing countries have the priority to eat first and then focus on energy.

Coming back to your questions— [applause]

Bäte: Sorry about that, [indistinct]

Ibrahim: Trees. When we talk about trees, I think like, most of the biggest powers thing planting a tree is the solution to climate change—that’s it. But planting trees, yes. We need to plant them. But how about keeping those who exist, the ecosystem that exists already? How about restore it? How about protect it? We can’t give the excuse by planting three trillion trees and cutting those that can make paper, that can make whatever they want and make more money for them. That’s the question.

So planting trees, it’s a second phase of the business. And we know how to do this restoration. Indigenous peoples in the Amazon, when you go to their land, is the most diverse ecosystem. It’s better than a national park. Because the government can’t protect the national park from fire or deforestations or from illegal mining. But indigenous peoples can protect their land. That’s why the ecosystem is more diverse there. It’s the same in the Congo Basin, because Chad of course is there as a country but it’s also part of the Congo Basin. That’s how we are protecting it.

So, we have the knowledge to do it. Let me give you one example of how we are restoring it. Like, my grandmother is the best technology ever. Because she can predict the weather, without having a cell phone or Internet. She can predict the weather by observing the wind direction, by observing the birds’ migration, by observing the tree flowers. She can can tell her people where they have to go to get to water and pastures. So this technology to restoring her ecosystem can protect her people. And that’s how we are getting protected even though we are the most impacted, but we are still in our field, and we are going to be in our field for far. So let us restore this ecosystem and join all together to plant the trees after.

Let me give you another example of trees, just very short. The [Great Green Wall] in Sahel. We say Sahel is a big land of desertification. But if communities come together, and each one of them takes the responsibility of restarting his own land, that’s the best way of planting trees. Not throwing in millions of them, but giving the people the responsibility to make them themselves because they know it is their survival. So how I’m seeing these tree plantings can be successful.

Blumenstein: Rajiv, how do you square this conflict between the developed world and the developing world and the role that each needs to play? You have big investments in Africa and in India.

Shah: And I, when I was in the Obama administration was part of both the Paris Agreement and and also the Sustainable Development Goals saying that we can achieve zero poverty by 2030. And both are in fact achievable and both can happen together. And it’s not that difficult to figure out how. First, the twenty largest countries in terms of emissions are absolutely where efforts to get to zero emission should start. And that is hard to imagine that being successful without government policy participation from China, the United States, and India. And right now, I’d say all three are going the wrong way. And even though China has done some things that are quite appropriate and notable, they’re still financing 150 gigawatts of new coal plants in China—much of it is actually in other countries around the world. The low-cost, state-supported financing is in Kenya, it’s in Guinea, it’s in India, it’s in Colombia. So I think it’s important to recognize that this is a global issue and the top twenty countries that emit have to have the politics and policies that say we’re serious about getting to reduction—and with all due respect to corporations, it’s very hard to see corporations using voluntary action to solve this problem.

Second, I actually do think we have to re-focus on the living standards and aspirations of the world’s bottom 2 billion. And it is possible now to provide renewable-based energy to meet the growing needs of that population. And even recent World Bank studies from last year are already out of date in terms of their own assessment of where the lowest-cost electrification strategy is from renewables. And I’m confident this year, in our one project in India we’ll be providing power based on solar mini grids to communities that have never had access to electricity, at fifteen cents a kilowatt-hour. At that price, it beats every other alternative. And I have met women who have sewing machines and say, “You know, I was finally able to get a power electric sewing machine, double, triple my income. Send my kids to school.” A gentleman who works on a farm that’s able to buy a rice huller and improve their post-harvest processing. Those are the kinds of things that will create employment, growth, and opportunity for the world’s bottom 2 billion, and if we do not take their aspirations seriously as part of this effort, we’re failing the other big challenge of our moment which is the deep inequality that threatens the politics, that threatens us from being able to do things on climate that matter.

And finally I would just say I do think there’s a tremendous amount of space to move from divestment to investment. Rockefeller and a bunch of other foundations have moved away from fossil fuels in their direct investments. But even more important than that, having incentives to create investment so we have the trillions of dollars to create the technologies and the solutions that are necessary, it’s not the only solution but it has to be part of the picture, and we’re proud to be associated with a number of those enterprises.

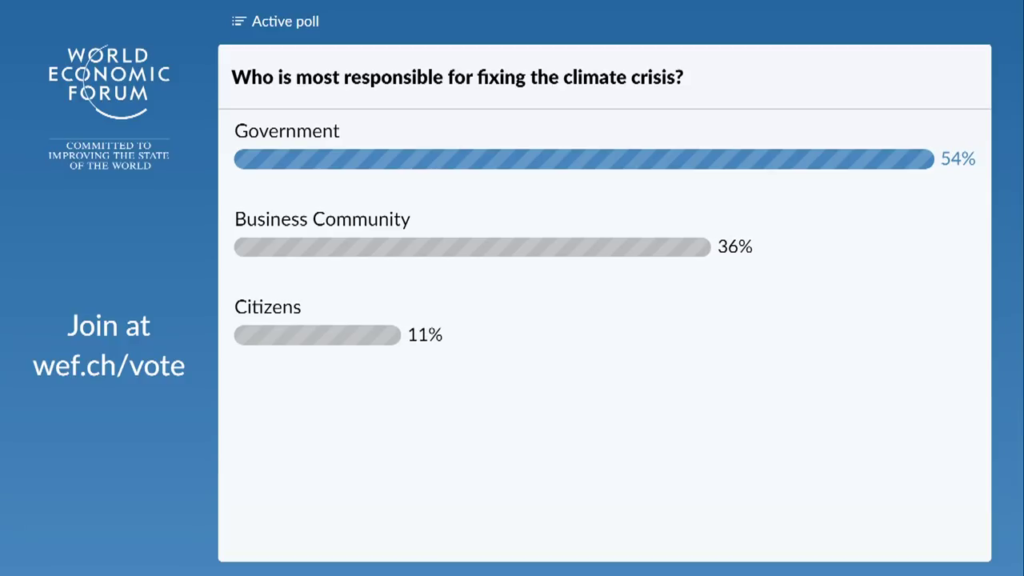

Blumenstein: I want to ask all of you some of your opinions. We’re going to queue to a question over who has the biggest responsibility for reducing emissions? Is it government? Is it the business community? Or citizens? If you could enter your responses. We’re not seeing much for citizens here, which is interesting—okay.

That’s fascinating.

So government seems to be in the pole position here, as many on the panel have said, of needing to play a bigger leadership role.

[Graph was animated through the prior commentary; this was the final position visible in the recording.]

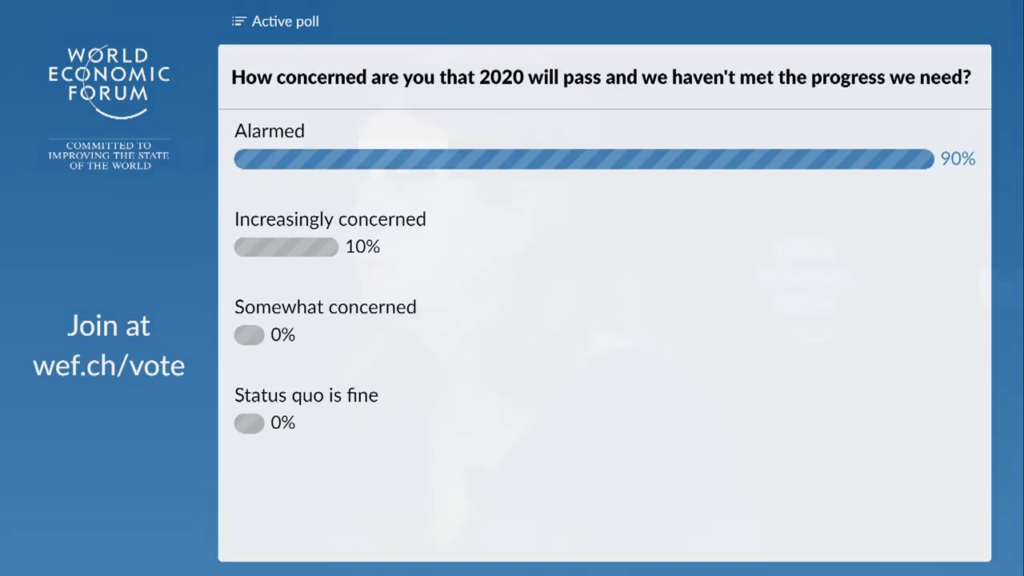

Can we queue to one more question? How concerned are you that 2020 will pass and we haven’t made the progress that we need? Somewhat concerned, alarmed, status quo is fine, not at all concerned.

Wow. Okay. Well Greta, you are…you are getting through, that’s for sure.

We have a lot of questions that have come in and our time is rapidly disappearing here. So, Oliver there’s an interesting question about nuclear power here, and I think to all the panelists. Now, Germany took a step back in nuclear power…you know, obviously with the Fukushima accident. What role does nuclear power play moving forward, in terms of reducing climate warming?

Bäte: I’m not an expert on technology so I’ll just say that up front. And unfortunately a lot of these things are discussed without facts. So—by the way, one of the things that we’re doing with net zero is to have what we call the science-based targets initiative driven by the United Nations. So we need the facts.

There are many ways to bring nuclear into the picture with more modern technology. So we wouldn’t exclude it. I would like to pick up one point that he has. [indicating Shah] The commercialization of new sources, sustainable sources of energy, has happened much faster than we could all imagine. So not just divestment of new fossil fuel but putting a lot more assets behind new technologies, and their scaling. Unfortunately we have many of these examples, but we’re not scaling fast enough.

So, where are the proper incentives, how do we scale that? So what I’m trying to pick up from Greta is, it is taking too long because we’re having too many anecdotes, too many nice stories, and too little systematic planning and execution. We need to move from words to action.

Blumenstein: Mm hm. Ma Jun is there anyway—I mean, the government of China obviously is very powerful. Your approach is to activate the private sector, largely. Is that letting the government off the hook?

Ma: [chuckles] Yeah. The government must play its role, for sure, you know. And the whole reason that we as an NGO can compile so much data is because the Chinese government in response to the public demand for data started rolling out to all this monitoring and data disclosure. And we also changed the legislation, making our supervision much tougher. But I do think that contrary to what many people would think, in China if the government tried to do something it can do something, you know. There’s also a limit there. So the government also needs people, you know, needs the public to send the clear message. And also the government also needs businesses to join the effort, especially now.

And now there’s such a vast developmental of IT technology. I would definitely agree with Oliver. I just recently met with our solar panel manufacturer. During the past ten years, there’s a 90% drop of the cost, and they said they’re on their way for another 90% drop, and we have the first solar panel power plant, which can generate power electricity cheaper than the coal power plants.

So I think all these are major opportunities. But we need motivation. We need the incentive for this to be tapped. All this technology is available. Nuclear you know, pushing the whole cost to the future generations with all this spent fuel disposal.

So I do think that now if we all share this view that our house is burning, our whole plant home is in danger, then we need to come together to make our voice heard, to motivate. You know, as citizens, as consumers, you can do so much. Because the whole business would respond to that if you choose that you care, you know. Changing your day-to-day behavior is important, but if we can play our role more smartly, tapping into all this new—

Blumenstein: Making the data more transparent.

Ma: Yeah. No technology. Then we can scale up our efforts and achieve our target in a practical and much sooner way.

Blumenstein: In meeting Greta’s challenge, I’d like to ask all of you what is the single thing, if you were talking to a peer about today’s panel, what is the single thing that you would recommend that we should do to avert a climate apocalypse? Anyone like to start?

Ibrahim: I can go. I think the single thing that I want, the emergency’s now. It’s not tomorrow. So, the action needs to be now. Because what are we waiting for? Forests burning? Food becoming difficult? But people dying. Nothing more for me than seeing the community that’s dying who do not have a future for tomorrow. Who cannot think about the next fifty coming years. So, the action has to happen now, and Davos is a big opportunity. Fifty years, so it’s now time to open all our minds, our eyes, from business to the big politician leaders who are here to take a radical step further, shift the economy to the clean one, and take the decisions to change all and every system to the sustainable one. To save their people. To save themselves. Indigenous people are saving ourselves with our knowledge, and it’s the time to listen to us. Give us our place. We can talk, and we know how to do it. We know how to protect it. So lie on our back, don’t be in our face, and give us the way to act all together right now. [applause]

Ma: Yeah, I want to say… I just want— Of course this sounds like advertising but you’re welcome to download the Blue Map app. Because you can see the world is…our home is on fire. We track the global air quality. And most of the time you know, China, India, we’re suffering from very severe air quality problems. But more recently we started seeing in the Southeast Asia, Borneo sometimes, all this burning, [crosstalk]and Amazon—

Blumenstein: Australia.

Ma: Australia. It’s hard to imagine. San Francisco. You know, LA. California, there’s bush fires. So we can see it’s on fire, but in the meantime you can see 3 million factories located on the digital map, color coded according to their level of performance. I challenge businesses to look into that because we are tracking hundreds of brands also on the app. You can see as consumers or business leaders how they perform. I hope we can come together based on that data transparency.

Bäte: Very tough. Very tough. I don’t want to say something that sounds great but is not doable. But I’m getting out— At the beginning of the week we said you know, we’ll be successful if we do 2X. We have to think as a startup and not like a 130 year-old company which we have, we have to do 10X in terms of getting the commitments. And we’ll try to do it as quickly as possible.

Blumenstein: So not just doubling, ten times what you started with. In how long?

Bäte: We don’t have thirty years, that’s for sure.

Blumenstein: Rajiv.

Shah: I think my big observation is that this takes all of us. And we you had that chart that said it’s 50-some percent government and the rest private sector. At the end of the day, we need governments to set policies, make agreements, and live up to those commitments and I agree with Greta’s observation that we’re nowhere near meeting those Paris commitments. As so many people felt they were insufficient as they were, and we’re gonna roll into Glasgow this year—at the end of this year, and I think people will see that we’re just not on a path where people are living up to the commitments that were made just a few years ago. So, governments have to offer real leadership. I applaud Allianz, and I think the private sector and companies have to take this on as well.

But I also think citizens matter. And citizen activists that are putting this issue on the map and making it the cause of our time. Citizen scientists who are inventing new solutions. Citizen activists who are working with indigenous populations. It’s so critical that we all think of this is something each of us has to do. Including changing the way we eat, changing the way we buy products, changing the way we live our lives, so that we can be part of the solution.

Blumenstein: I’d like you all to join me in thanking Greta and our panelists for a fascinating discussion. [applause]