Inke Arns: Thanks. It’s amazing to be here. I hope you can hear me and the technology is working.

So I’m going to briefly introduce you to Afro-Tech and the Future of Re-Invention. It’s an exhibition that is currently on view in the [?] area at HMKV until late April. And it’s just uh…there’s a lot of gold in the exhibition.

So what’s the exhibition about? The exhibition Afro-Tech and the Future of Re-Invention puts Afrofuturism in dialogue with alternative technological solutions and imaginations. The speculative narratives unfolding in the artworks on display (and we’ll talk about them later) are confronted with actual inventions from maker scenes in different African countries. This creates a double shift of perspective: while the artworks project decidedly African and diasporic science fiction visions, the real devices appear as evidence of a technological development that is already underway. The exhibition thus presents Africa as a continent of technological innovation. And I will explain to you later why this is so, why we do this.

This is just an overview of the artists in the exhibition. Twenty artists and twelve tech projects in the exhibition. They are presented together. And I will also explain later how come this is so.

Before I talk about the exhibition and go a little bit more deeply into the contents, I want to tell you a little bit more about the research I did this before doing this exhibition, and the research that was really crucial for developing this project.

So in 2014, with my colleague Anna Bergner, who is a design professor at the University of Applied Arts and Sciences in Coburg and who has been researching a lot in maker spaces and magazines and so on, we traveled to three countries of that big continent. So we went to Kenya at the eastern coast, we went to South Africa at the southern coast, and we went to Nigeria, in order to research what people were doing with technology.

This was the first logo, which Anna developed. I think it’s a really beautiful logo. It obviously shows you the silhouette of the continent with a wheel, which is very important. A satellite dish, a helicopter rotor, surveillance camera, flashlights, and also something like a cable that looks like an elephant’s mouth.

So, when we started we had certain ideas and wishes. We wanted to look at the use, the adaptation, and the reinvention or invention of technologies—new technologies—in those three African countries.

And it was very interesting because in 2014, before going there, we also read a lot of stuff on the Internet. For example there was this interesting article by Ethan Zuckerman, Africa’s hackers are today’s world-class tech innovators which was published in Wired, for example.

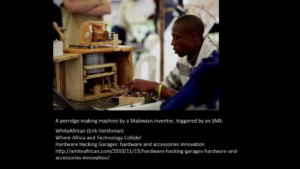

Then there was a very—and I’m just pointing you to these articles in case you’re interested in looking at who’s writing about technology in Africa. WhiteAfrican, who’s actually Eric Hersman from Nairobi, he’s running this blog where you can find lots of really interesting entries.

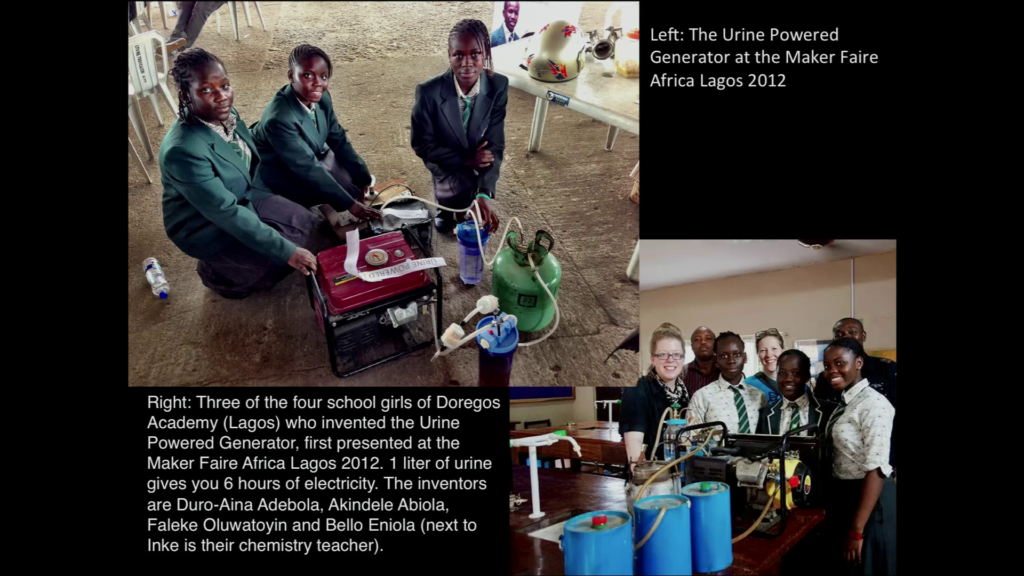

This is a very interesting and important guy, Emeka Okafor. He’s part of a very big family from Nigeria. And he emigrated to the US. He’s living in New York City and he is one of the people who started the Maker Faire Africa project. And he also ran the Maker Faire Africa in Lagos in 2012. So, his online project is Timbuktu Chronicles, so you might want to check out what he’s writing there.

This is just a really beautiful poster of the 2012 Maker Faire Africa in Lagos, which gave us a lot of ideas, actually, where to start our research and where to look at and—okay, that’s another rather funny article, Want to Become an Internet Billionaire? Move to Africa, from 2011 already, and the map actually shows you the projected undersea cables in May 2013.

I’m not going to read you all of this. Just to tell you, we wrote a kind of FAQ before we went, because we wanted to make very clear what we were interested in and what not. And just to give you an idea, we were interested in “people doing strange things with technology, electricity, software. Those who are not contending themselves with corporate solutions designed for the global North and who, out of this dissatisfaction are starting to develop their own solutions.” So, that’s what we were looking for.

That’s just my first impression of Nairobi.

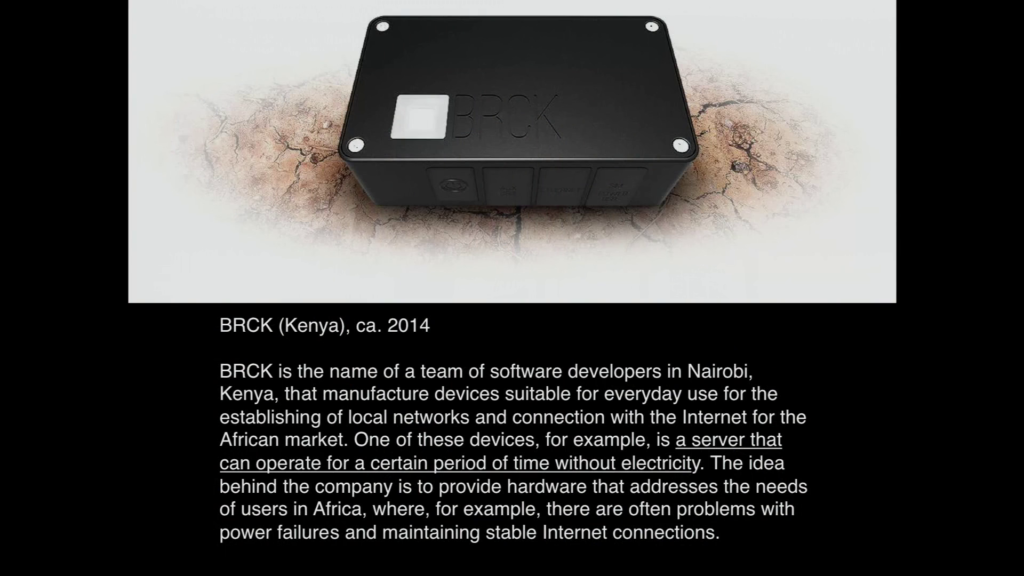

And the people we met were quite amazing. For example here in Nairobi in Kenya, we met this Erik Hersman, WhiteAfrican, who had at that time been developing the first Internet server that could work without electricity—or without constant power connection. Which is something very important in Africa because in some countries, or let’s say many countries, there are constant power failures and many people of course use power generators, which consume a lot of gasoline, in order to become independent of those power cuts. And with a with a laptop like this it’s not a problem because it can kind of survive two hours, three hours without electricity. But the servers for Internet connectivity can’t. And so that’s why they developed this machine which has a built-in battery, basically.

Somebody else I met in South Africa has developed this project Robohand. And the guy who invented the project is Richard Van As from South Africa. You can see him in the yellow t‑shirt. He actually used to work as a carpenter. And at some point in 2011 or so, he had a serious accident. He kind of cut off half of his hand. And so when he went to the hospital and had to face medical treatment, he suddenly realized that so he basically could not pay for an artificial hand. So he decided to make one himself. And at that time 3D printing was just up on the horizon, and he invented the solution for himself. But then in the process of making this fully mechanical, non-electrical hand which is fully functional, he realized that the solution could not only maybe work for him but also for others. And so that’s when he decided to put the files online, and they’re accessible for anybody who has a 3D printer, basically. And that can be adapted to the individual needs. This green one is a hand that we printed out for the exhibition in Dortumd.

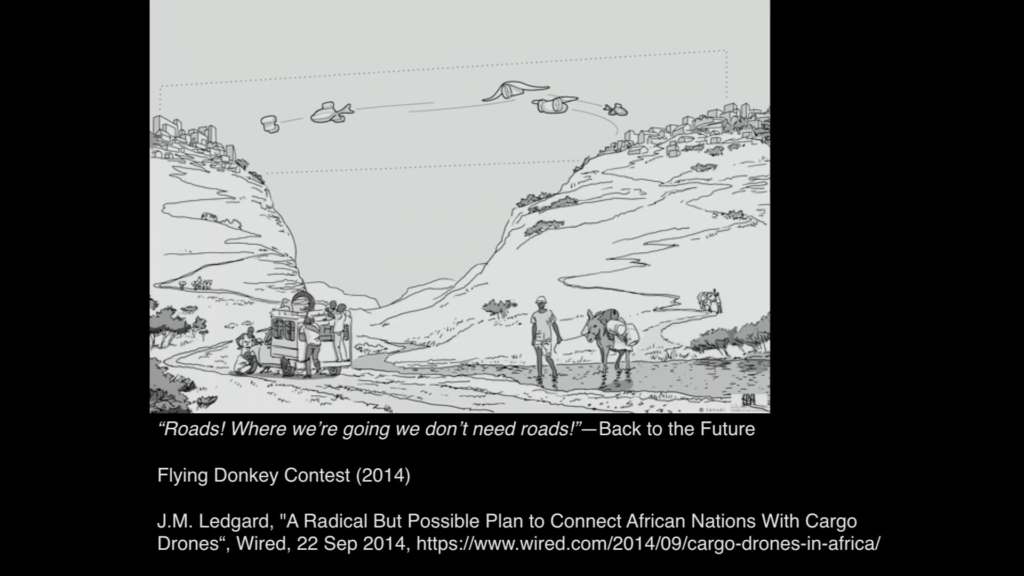

A Radical But Possible Plan to Connect African Nations With Cargo Drones, Wired, 9/22/2014

Okay, the flying donkey challenge, or contest, was also quite popular at the time. I think they kind of discontinued it because of several bomb attacks and they could not follow up on this. But the idea basically, when you don’t have infrastructure, roads and stuff, why not use transport drones.

Another very interesting project is a project that was presented at the Maker Fair Africa in Lagos in 2012. It’s a project by four schoolgirls who built a generator—it’s a power generator—which is not running on gasoline but which is running on urine. And apparently you can produce six hours of electricity with one liter of urine. They were about to install it into their school system.

So, just to give you some ideas that resulted from this research trip. Very often I had the feeling, okay there is a serious lack of infrastructure, a serious lack of material, you know, infrastructure. There’s not a cash machine at every street corner. There’s maybe not roads that are good enough to be used on an everyday basis. So there’s really a serious lack of physical infrastructure.

And what I noticed is that it’s not about catching up but somehow it’s about jumping over, right. It’s about going directly to the next level. So going directly wireless. And I guess some of you know that, or many of you might know, that M‑Pesa was introduced very early on. It’s a way of paying with your mobile phone without the need of having a bank account. Of course the usage of mobile telephony is very widespread in Africa. And so a lot of ideas suddenly somehow became very virulent, so to speak, out of this idea of jumping to the next level.

For the project, it meant that what I had seen in those three countries somehow did not correspond to what you usually see in the media—television, or on the newspaper. You always read about there’s the next famine, there’s poverty, there’s hunger, corrupt regimes and so on. It certainly all exists. Definitely. But there’s also something else. When we had the opening of the exhibition I said there’s normality in Africa, you know. So that’s why we decided to present Africa as the continent of technological innovation. It’s a different kind of extreme.

So, you might wonder how does Afrofuturism come into the game. For a long time I did not know what to do with these findings, you know. I was very unsure how to develop the whole project further and then I started talking to a colleague of mine, Fabian Saavedra-Lara. Because somehow I had the feeling I’m missing a kind of narrative. Okay, this idea of jumping to the next level, it’s a nice idea but…mmm. And the idea of presenting Africa as a continent of technological innovation is also quite interesting but somehow there was a lack of narrative. So Fabian, he suggested to look at Afrofuturism.

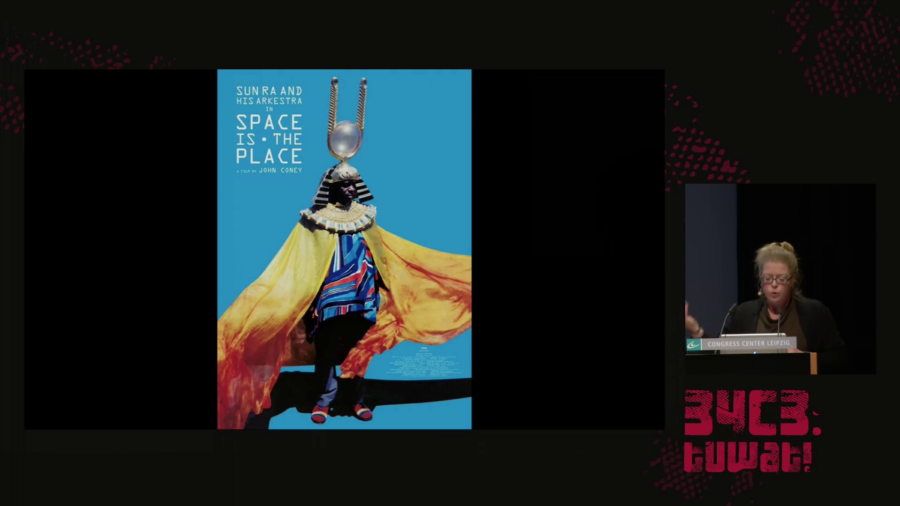

So what is Afrofuturism? Afrofuturism is clearly not something that comes from Africa, interestingly. But it’s let’s say a science fiction narrative that developed let’s say in the 1950s in the US. So it’s Afro-American culture, and one of the protagonists is actually Sun Ra, a jazz musician who always claimed to be from the planet Saturn, not from the planet Earth but from Saturn. And as you can see he loved dressing up like a pharaoh. So those two references were very important. The reference to ancient Egypt, so let’s say high culture in Africa. And at the same time the reference to space, to outer space. And these are two very important references for Afrofuturism. And you will find these references in many let’s say science fiction stories, narratives. So when you’re being denied your own place in the present time, Afrofuturism has been looking for alternative spaces, and also times. So that’s why space is an alternative place. And also let’s say the moving into the future or into the very far away past is an option, became important in Afrofuturism.

So maybe you have wondered why we have such a very strange design. On the right-hand side it’s the building we are located in. It’s Dortmunder U; it’s the former union brewery. And it has this beautiful logo on top of the roof which obviously stands for “union,” this beer brand. But our designers actually found this parallel in Sun Ra’s hairdo, let’s say. So that’s why we actually developed this design.

So let me tell you a little bit about the exhibition. So John Akomfrah’s short and experimental documentary film The Last Angel of History examines the relationships between pan-African culture, science fiction, intergalactic travel, and rapidly-developing computer technology.

The short film Afronauts from the Ghanaian director Frances Bodomo looks at the real history of a planned space program in Zambia of the 1960s, a time at which political utopias encountered technological progress. And this is actually the story of a 17 year-old girl in Zambia who was supposed to be sent to the moon.

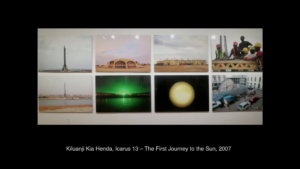

Kiluanji Kia Henda’s photographs show futuristic architectures in the Angolan capital of Luanda. The artist reinterprets those post-colonial buildings in Icarus 13 into proof of the first African journey to the sun.

Kapwani Kiwanga in her Sun Ra Repatriation Project has the goal of bringing Sun Ra back to his actual planet of origin, Saturn. Sun Ra, who died in 1993, was a jazz musician. He claimed to originate from the planet Saturn and represented the philosophy of the Astro Black, which confirmed his extraterrestrial origin. So in this video, she actually interviews a lot of scientists, some of them involved in the SETI program (Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence) how to prove…is there a way to prove that Sun Ra really returned to his planet of origin. And she actually manages to prove it, obviously.

Taking the work of the cosmic jazz musician Ra again as a starting point, the speculative narrative of Soda_Jerk examines the connection between science fiction and social policy in the black Atlantic music culture. In the exhibition, Astro Black is presented as a two-channel video installation with four episodes alternating between the two screens.

So this was a selection of projects that deal with outer space, with space travel. Then we also have a lot of projects that deal with the sea. With the deep sea, with the Atlantic. And I’m going to present you two or three of those.

So Drexciya. The legendary Detroit techno duo Drexciya developed imaginary worlds inspired by Afrofuturism in many concept albums. In their releases, Drexciya is also the name of a legendary city beneath the sea. This Afrofuturist Atlantis is populated by the descendants of pregnant women that were taken as slaves from various countries of Africa and thrown overboard and murdered during the crossing of the Atlantic. According to the legend, their unborn children survived in the womb and developed the ability to breathe and live underwater. They founded an unknown underwater civilization that was in possession of utopian technologies.

The South Africa-based artist Tabita Rezaire deals with the sea as a storehouse for pain, lost stories, and memories in the era of colonialism in Deep Down Tidal. That’s the work we see here. While it also contains the deep sea, it also contains the global infrastructure of our present day telecommunications within it. So she really follows, she actually overlays, she finds a parallel between the undersea telecommunication cables and the roots of the slave ships that have traveled from Western Africa to the so-called New World.

The filmmaker Simon Rittmeier, in his film Drexciya which you can also see tonight, picks up the myth of the same name in order to use the methods of science fiction to tell of the images circulating in media today, and about discussion of the refugee crisis.

Another film that you can also see tonight—so tonight is a video program of three films, which in the end I will show you a slide. This is actually Naked Reality by Jean-Pierre Bekolo. It’s an afrofuturist science fiction film located 150 years in the future. The cities of Africa have grown together to form a gigantic dystopian metropolis in the film of the Cameroonian filmmaker. The protagonist Wanita leaves the house one morning not knowing that her first prayer to the ancestors has initiated her journey to Dimsi, a world one cannot see.

Louis Hennderson, that’s the third film you can see tonight, Lettres du Voyant, Letters of the Seer, is a film essay that uses documentary methods to tell of spiritism and technology in present day Ghana. The narrative of the film revolves around a mysterious practice known as Sakawa: Internet scams, fraudulent mass emails, that is enriched with voodoo magic.

Fabrice Monteiro the Belgian-Beninese photographer comments on environmental destruction in various regions of Africa in his photographic work The Prophecy. In his images he stages fantastic entities he has designed together with the designer Doulsy from Dakar in apocalyptic landscapes. We’re showing four of these pictures here. I only show you one, and this is obviously dealing with computer trash.

I’m slowly coming to an end. The tech projects, I told you in the beginning we have twelve tech projects in the exhibition. They cover a very wide variety of areas. I already told you about BRCK, from Kenya, which is an Internet server that also ensures access to the Internet even without a stable power supply.

M‑Pesa from Kenya is a cash-free method of payment that functions via mobile telephone which requires no bank account.

And there’s the project Uko Wapi from Germany. I mean, the people who develop it, they’re working in Germany and in Africa. Uko Wapi means as much as “where are you?” It’s an innovative address app that reliably also finds locations in areas without an existing address system.

Another important area is that of health and medicine. I already showed you Robohand. Robohand provides prostheses—fingers, hands, and legs—for printing out oneself with a 3D printer at a fraction of the price of conventional medical prostheses.

GiftedMom is an app that provides expecting mothers with useful information and contributes to sexual education.

Chowberry from Nigeria combats hunger through innovative use of the expiration dates of food products. This could also be quite interesting for here. The inventor, Oscar Ekponimo, he wants to avoid food waste.

And then there’s a project called a CardioPad that helps with medical diagnosis in areas with low populations and creates a direct connection with medical specialists.

Juakaliscope from Kenya is a completely functional microscope from the 3D printer.

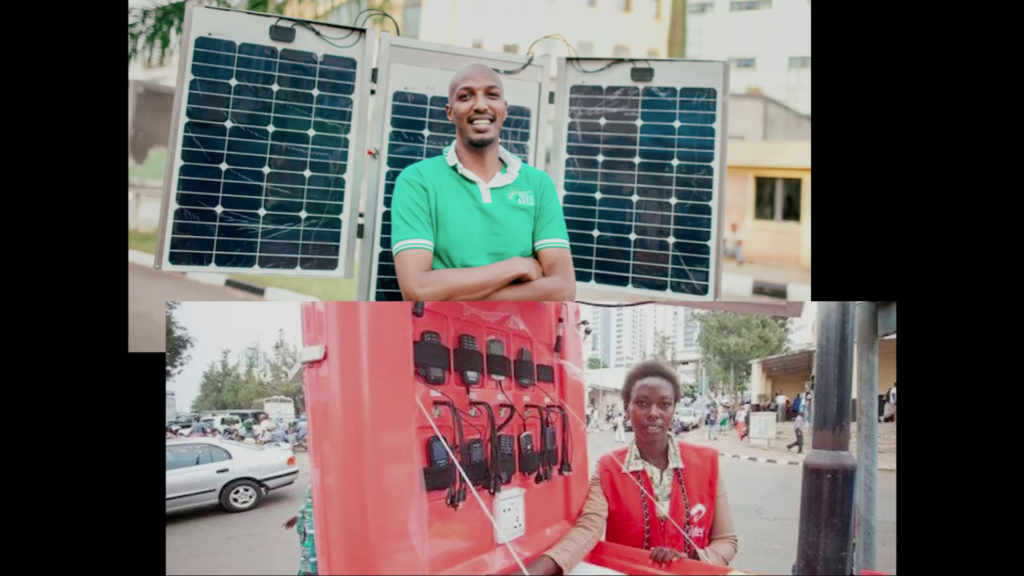

And Shiriki Hub, that’s the last image I would like to show you. This is Henri Nyakarundi from Rwanda. It’s a kind of solar kiosk which people can use for recharging their mobile phones and mobile devices. And Henry, he also came to Dortmund. We had a one-week festival and we invited several of the inventors. And Henry, he told me…because he builds these kiosks and he kind of rents them out to people. So people can rent them and they can make money on recharging telephones. And he told me, “Oh, I’m not employing young men. I want to work with young women, especially young mothers because they feel very responsible.” So he’s predominantly employing young mothers to run these kiosks.

So if you’re interested in more stuff, there’s a travel blog. Obviously there’s a video about the exhibition. There has been some very interesting press coverage. And the film screening I would like to point you to is every night from tonight at ten o’clock in the video lounge. It’s those three films. And I would like to thank you for your attention and I’m here for for questions and answers, obviously. Thank you.

Further Reference

Session archive page