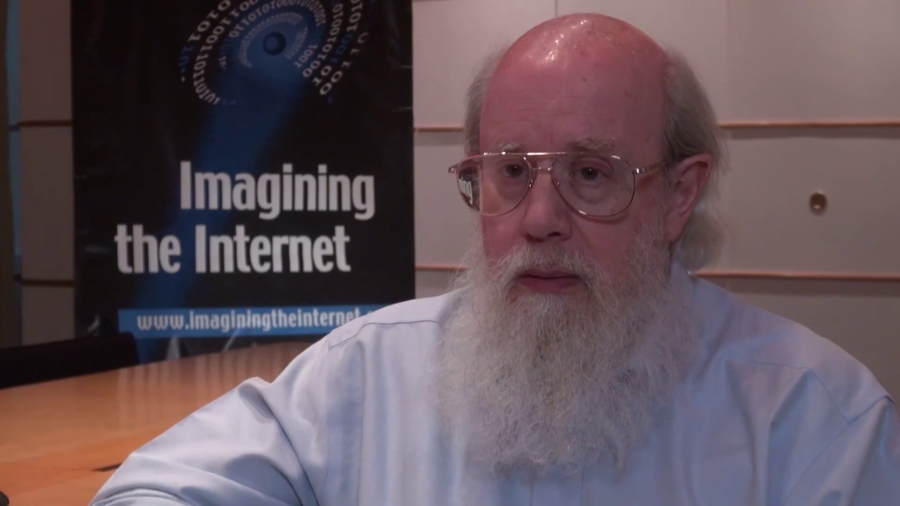

Scott Bradner: I started out working on the Internet Engineering Task Force in 1990, was selected to be one of the managers in the IESG—Internet Engineering Steering Group in about 1993, and was on the Steering Group for a decade. Also in 1993 I was elected to the ISOC board, and was on the board for six years. Then became the ISOC Vice President for Standards a couple years before I got off the board, then stayed in that role til ’95. And in ’95 became the secretary to the board, and I still am. So I’ve been on the ISOC board mailing list since 1993 and worked in the Internet space, in standards in particular, for the decade there and went into management but also in just working groups and the like. I was one of the two people that were given the task of coming up with IP Next Generation, which is now known as IP version 6 and so…was involved.

Helped found NEARnet, which was a regional data network in Northeast US. It was the highest-speed network at the time back in ’88. So it’s been a fun time.

Intertitle: Describe one of the breakthrough moments of the Internet in which you have been a key participant?

Bradner: I don’t know I was a key participant, I was a participant. The breakthrough moment really was the deployment of TCP/IP on the ARPANET. I had gotten onto the ARPANET—Harvard had gotten onto the ARPANET—in 1971. I had an account at that time. But the ARPANET in the early days was a network that connected computers together.

In January of 1983, they deployed the TCP/IP protocol on the ARPANET. And that switched it from something that was connecting computers, to something that was connecting networks. So Internet, as in network of networks, that started in January of 1983. Shortly after that, with the development of some of the regional networks from National Science Foundation, Harvard got connected up to TCP/IP in ’83 timeframe, and to the NSFNET in ’86 timeframe. And those were very important eras because they proved that high-speed packet networks would work. Particularly the deployment of IP version 4—Internet Protocol version 4—meant that we were connecting networks together, which allowed computers in various places to talk to each other rather than one computer at Harvard talking to one computer at Stanford.

Intertitle: Describe the state of the Internet today with a weather analogy and explain why.

Bradner: Just like the world, the world doesn’t have a single type of weather across it. So the Internet doesn’t have a single type of weather. The weather forecast for the Internet is mixed. We are at a very tough time right now. For most of its life up until…certainly up until the late 1990s, most of the traditional world, traditional telecommunications world—the regulators and the standards bodies—completely ignored the Internet because they thought it was a toy. They thought it wasn’t useful for anything. It was only as the usage exploded in the late 1990s that governments, and regulators, and traditional standards bodies began to really understand that there was something here. And they’ve been trying to figure out how to get involved in it since. And we are on the cusp of that. And that means that there’s a stormfront,

Now, whether that stormfront is going to come over us or avoid us, we don’t know yet. But certainly the chances are…there is risk. There’s significant risk of some very rough times for the Internet as we know it. It’ll be a different Internet. If the traditional standards bodies had developed the technology of the Internet, it wouldn’t be what we have today. It wouldn’t be that you could set up a web site. It would be that the carrier, the telephone company, could set up a web site for you. And that’s a different model. And that’s the risk that we’re in right now, is that the governments want to control it. As we’ve seen in Turkey in the last few weeks, when a government gets poked, the reaction is to shut things down. And the developments of the political sphere risk enabling that.

Intertitle: What are your greatest hopes and fears for the future of the Internet?

Bradner: Biggest concern is the one of regulatory impact. There’s an awful lotta governments in the world that don’t like the idea of citizens being enabled. Of citizens being able to talk to citizens. They want to control the data flow, the information flow. And that kind of government would if they could change how the Internet runs. And in that context, that would dramatically change our ability to actually communicate over it. So that’s the biggest fear.

The hope is that the people who’re on the ground, who have used the Internet, the kids and not-so-kids that have been working on this, being enabled by it, communicating by it, whether it’s social media or anything else, whose lives are built around that, will see the danger and will rally against it.

I was having lunch at the Chinese restaurant in the hotel here on Sunday, I guess it was. And there was a young woman and two kids at the table next to me. And the kids were maybe three and four; little girls. And one of the little girls was just buried in smartphone. Just zipping through it to try and get something on it. And that’s the generation which is enabled by this. And if the powers that be try to control it, try to reduce what you can see and how you can communicate, the hope is that those people—and you—and your generation, will see that as a risk, will see that as a threat.

Intertitle: What action should be taken to ensure the best possible future?

Bradner: Pay attention. You can’t leave it to others. You have to pay attention. That this is…while it’s in the political sphere, it is politicians talking to politicians, trying to figure out how to control this thing. It’s in your future. It’s in all of our futures, but you’ve got more of a future than I. And so it’s more important to you to keep track of this, to see what’s going on and to speak up. And to agitate. And to understand what’s at risk.