Henry Jenkins: As the head of comparative media studies, I have to say that one of the things I admire most about Neil is the degree to which his work spans so many different media.

If we think about comics, we of course immediately think of Sandman and Death: The High Cost of Living, but also we’d want to think about Books of Magic, Violent Cases, The Tragical Comedy or Comical Tragedy of Mr. Punch, 1602, The Eternals, many many other books. He’s a figure in children’s literature, the author of The Day I Swapped My Dad for Two Goldfish, The Wolves in the Walls, The Dangerous Alphabet, which is about to come out. And prose works, American Gods, Anansi Boys, Angels and Visitations, Coraline. Television, the “Day of the Dead” episode of Babylon 5, an BBC’s Neverwhere series. And film, Mirrormask, Stardust, Beowulf, the English translation of Princess Mononoke. And audio recordings, Warning: Contains Language, which is perhaps my favorite title of Gaiman’s oeuvre.

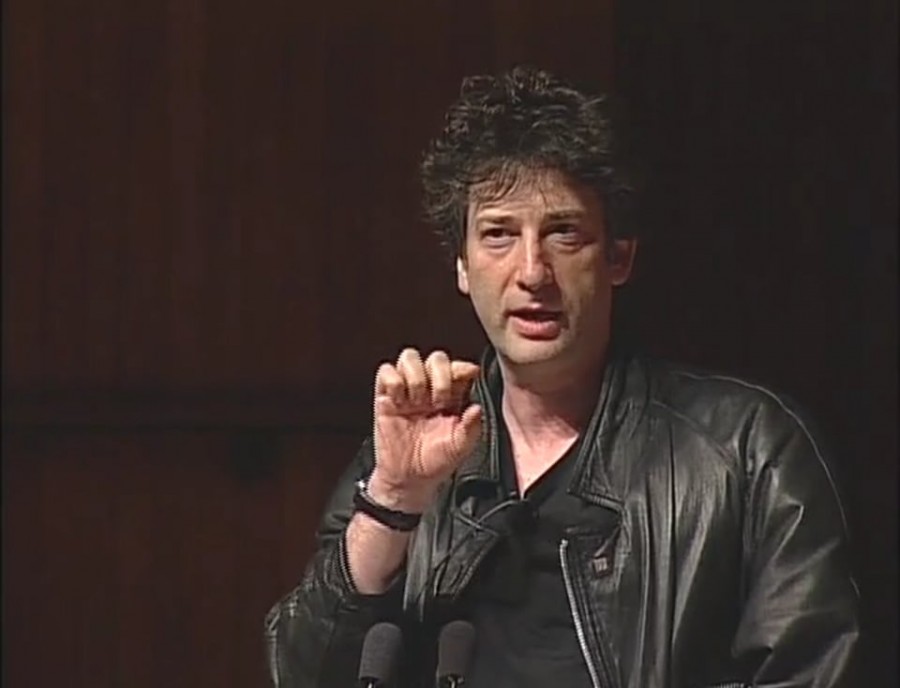

That said, I think you’ve heard enough from this stuffy old guy, and let me turn the floor over to Neil Gaiman, who I’m delighted to bring to this audience.

Neil Gaiman: It was a terrible title, Warning: Contains Language. It took us about a year and a half to persuade Diamond not to carry it in their catalog as “Untitled Neil Gaiman Album” and then “Warning: contains extremely bad language” as a warning. We kept going back to Diamond and saying, “No no, that’s the title.”

And they’d say, “What do you mean that’s the title?”

“That’s the title. It’s called Warning: Contains Language. It’s a joke.”

Last clever title I gave anything.

So, thank you, and thank you all for coming. I thought before I actually did the talk, I would begin by reading something by somebody else, which is not something I get to do very often in public. This will be the second time that I’ve read this, and this is a speech that Alan Moore wrote when Julie died, and sent me to read at Julie’s memorial. And how often do you get to get up at MIT and read an Alan Moore speech?

Just off the plane from England, anything except fresh out of Kennedy, within an hour or two we’d all been introduced to Julie, all us early-80s economic migrants, awestruck, wide-eyed, staring like religiously-converted lemurs as at last we met our childhood’s god, the intergalactic cabby who wouldn’t shut up, the curator of the space museum.

We loved Julie in the way that we’d love anyone we’d known since we were small, who’d shared with us that secret rustling flashlight-dazzled space beneath the midnight counterpane. We loved him in the way that we loved covers with gorillas on.

We followed at his heels, a quacking flock, along the migraine-yellow dot-toned hallways of the DC offices, and if he thought of us as irritating Carl Barks nephews, as the Hueys, Deweys, and Louies that he’s never wanted, then he didn’t let it show. Quite the reverse. Julie indulged us like a visiting school trip for pale, consumptive, English orphans. Fragile, coughing invalids at Fresh Air Camp.

He sneaked us presents. File copies of some treasured Mystery in Space pulled from the morgue drawers in his office, from which rose the perfume of his life, long decades of pulp pages, 50,000 comic racks in every corner magazine store that you ever visited or dreamed about.

He knew a captive audience when he saw one, and appreciated our appreciating. All the anecdotes were new to us, the creaking, chair-bound jokes fresh as this morning’s lox. The funeral for a much-feared fellow editor he told us of where at the section of a service set aside for testaments and kindly words concerning the deceased stretched into long, embarrassed silence, until someone at the back stood up and ventured the opinion that the late lamented’s brother had been worse.

We were a pushover. He made us laugh, he knocked us dead, and then there was the scrapbook with its pages full of letters, pictures, signatures. “I am, sir, your devoted servant, H.P. Lovecraft.” Photographs of Julie, young with diamond-cutter eyes behind wire-rimmed spectacles. Men in dark coats and homburg hats on winter corners in New York, gray vapor twisting up from manhole covers, from cigars. “You see the crewcut kid, that newsboy there? That’s Bradbury.” We’d gape and nod. Could not possibly have been more impressed if he’d said, “See that old guy in the toga standing by Ed Hamilton? That’s Zeus.”

And now we hear that Julie has been…discontinued? Cancelled? But they said the same about Green Lantern and The Flash back in the early 50s, so we can’t be certain. This is comics. There’ll be some way around it, be some parallel world. Earth‑4 Julie, born thirty years later to account for problems in the continuity, and decked out in a jazzier, more streamlined outfit. A funny, brilliant, endlessly enthusiastic twelve-year-old got up in an old man suit, Julie spent his life mining the gold seam of the future. He is too big then to ever truly be swallowed by the past.

He was a friend, he was an inspiration, he was the founder of our dreams. He ruined my reputation as a gentle pacifist by claiming that I’d seized him by the throat and sworn to kill him if he didn’t let me write his final episode of Superman. And how now am I supposed to contradict a classic Julius Schwartz yarn? So, alright it’s true. I picked him up and shook him like a British nanny, and I hope wherever he is now he’s satisfied by this shame-faced confession.

Goodnight, Julie. It’s been our privilege to have known you. You were the best.

Alan Moore, Northampton, March 17, 2004

Right. So this is the lecture‑y bit.

There are about 1,200 of us here, and at least one of was still sitting in his hotel room at 4:45 scribbling bits of this.

It’s the job of the creator to explode. It is the task of the academic to walk around the bomb site gathering the shrapnel, to figure out what kind of an explosion it was, how much damage it was meant to do, and how close it came to achieving that. As a writer, I’m much more comfortable exploding than talking about explosions. So if I pull examples of something, it’ll be from other peoples’ work and not mine. This also will make me look like less of an egotistical maniac when clips from this talk go up on YouTube.

Last time I was here it was 2001, and it was in the shadow of September the 11th, and I learned a lot about MIT by making a joke in an unpublished short story that I read about a web site, which by the end of that evening, the title, the web site had been registered and had a webmistress.

What is genre? I think it’s probably a set of assumptions, and it’s a loose contract between a creator and an audience. But for most of you, genre is something that tells you where to look in a book shop or a video store. Because there are too many books out there. So you need to make it easier on the people who shelve them, and on the people who are looking for them, by limiting the number of places they’re going to be looking. So you give them places not to look. That is the simplicity of book shelving. It tells you what not to read, and it tells you where not to go.

You go, “I’m not interested in Romance.” You can skip great big areas of a book shop. You go, “Young adult fiction, why would I want to go there?” You don’t have to walk down there. Now, the trouble is that Sturgeon’s Law (I’m at MIT, I can quote Sturgeon’s Law.) is a law propounded by Theodore Sturgeon, a science fiction writer, who in an interview was talking about science fiction. He said, “Well of of course 90% of science fiction is crap, but then again 90% of everything is crap.” And Sturgeon’s Law applies to the fields that I know something about, which would include science fiction and fantasy and horror and children’s books and mainstream fiction and non-fiction and biography, but I’m sure it equally applies to the places in the book shops that I don’t go, including the cookbook area and the supernatural romances. Because the corollary to Sturgeon’s Law is that 10% of whatever you’re looking at is probably going to be anywhere from good to excellent. And it’s true, I think, for all genre fiction.

Genre fiction, it’s always worth remembering, is relentlessly Darwinian. Books come, books go. Huge turnover, lots of them get published. Many have been unjustly forgotten. Very few get unjustly remembered. That rapid turnover tends to remove the 90% of the dross from the shelves, replacing it with a different 90% of dross. But it also leaves you (particularly with something like children’s literature) with a core canon that tends to be remarkably solid.

Now, life (and this is something you think about a lot when you write fiction) does not obey genre rules. It lurches easily, or uneasily, from soap opera to farce, office romance to medical drama to police procedural by way of pornography, sometimes in hours. On my way to a friend’s funeral, I saw an airline passenger stand up, bang his head on an overhead compartment, opening it, sending the contents over a hapless flight attendant in the most perfectly-timed and most perfectly-performed piece of slapstick I’ve ever encountered.

Life lurches. Genre offers predictability within certain constraints. But then, especially if you make the stuff, you start asking yourself “well, what is genre?” Because it’s not subject matter. It’s not tone. For me, the answer came when I read a book more or less by accident. It was sent to me to review, and it shouldn’t have been, but it turned up and so I read it. I read a book by an American film professor named Linda Williams, and it was her study of hardcore pornographic movies called Hardcore and sub-titled “Power, Pleasure, and the ‘Frenzy of the Visible’ ” which made me rethink everything I thought I knew about what made something genre, and what genre was. I thought I would share those insights with you.

Just as a sidenote here, before I get on to this, because this is one of those moments where I can leave you on tenterhooks and know you will still be here for me when I get back to my subject. I was in Melbourne, Australia a few weeks ago at the Children’s Book Congress of all Australian teachers and academics, and I had to give a talk. I was writing the talk and really enjoying it, and I suddenly got onto the subject of genre and I suddenly found myself writing a lot of stuff about hardcore pornography and going, “I really cannot give this talk at nine o’clock in the morning to a bunch of 6th grade teachers and children’s librarians. It will not work.” So I put it all aside and went, “I bet they’ll lap it up at MIT.”

So back into genre.

I’ve always known when you’re reading fiction, and especially when you start writing it, you know some things are not like other things. But you’re not entirely sure why. For me, the moment that my eyes peeled was the moment that Professor Williams suggested that pornographic films could best be understood by comparing them to musicals.

In a musical, you are going to have different kinds of song. You will have solo numbers, duets, trios, full choruses. You will have songs sung by men to women and by women to men. You will have many men singing together. You will have slow songs, and fast songs, and happy songs.

Now, you stop and think about that. You go, “Well, in a pornographic film you need the same kind of variance.” And in a musical, the plot exists in order to allow you to get from song to song, and also of course to stop all of the songs happening at once. So the hardcore pornographic film. The plot exists to stop all of the sex happening at the same time.

Furthermore, and possibly most importantly, the songs in a musical are— They’re not what you’re there for, as you’re there for the whole thing, the story and the songs and the dancing and the scenery and everything, but they are the things which if they were not there, you as a member of the audience would feel cheated. You’ve gone to a musical and nobody sings…? What kind of a musical is this?

The same goes for pornographic films. Many many years ago, I was on a signing tour with Dave McKean, and we were in a small English town trying to finish a comic which we were doing for Bryan Talbot’s birthday for reasons that I have long since forgotten. In England at that time, television was done by midnight, but we’re still sitting there doing this comic. So we turned on the only thing that there was, which was the pay-per-view porn channel. But in this particular little English town, they’d done something very very clever to the pay-per-view pornography, which was remove the sex from it. And Dave and I drew this comic watching a film which as far as we could tell was about a bunch of tourists who went off to a little Greek island together, and every now and then for reasons that you could never quite follow, they would go off in groups or one, two, or three. They’d head off into a little cottage. And then the sun would go down.

This was not a satisfying cinematic experience.

If you take the sex acts out of a porn film, if you take out the songs from a musical, if you take out the gun fights from a Western, then you don’t have the thing there that the person came to see. And when I understood that, I understood so much more. It was as if a light had been turned on in my head because it answered the question I’d been asking since I was a kid. I knew that there were spy novels, and I knew there were novels with spies in them that weren’t quite the same. I knew that there were cowboy books, and cowboy films, and there were also books and films that took place amongst the cowboys in the American West that weren’t cowboy films. But I didn’t understand how to tell the difference, and suddenly I did.

If the plot is a machine that allows you to get from set piece to set piece, and the set pieces are things without which the reader or the viewer would feel cheated, then whatever it is, it’s genre. If the plot exists to get you from the lone cowboy riding into town to the first gun fight to the cattle rustling to a showdown, then it’s a Western. If those are simply things that happen on the way, then it’s a novel or a film or a comic set in the West. If every event is part of the plot, if the whole thing is important, if there aren’t any scenes that exist to allow you to take your reader to the next moment that the reader or the viewer feels is the thing that he or she paid her money to get in to see, then it’s a story, and genre becomes irrelevant.

Subject matter doesn’t make genre. Having said that, there are some huge advantages to genre, one of which is as a creator it gives you something to play to and play against. It gives you a net and it gives you a court to play on. (I wrote “Sometimes it gives you the balls” but then I decided not to say that line.)

Another advantage of genre for me is that it privileges story. Stories come in patterns, and those patterns influence the stories that come after them. In the 80s as a very young journalist, I was once handed a very high pile of best-selling romances, books with one-word titles like Lace and Scruples. I was told to write 3,000 words about them. So I went off and I read them with initial puzzlement and then slow delight as I realized the reasons why they seemed so familiar was that they were. They were retellings of stories I knew, old ones since I was a boy, all retold in the here and now and spiced with sex and money. And although the genre in question was known in British publishing at the time as “shopping and fucking,” the books were really neither about the shopping nor the fucking, but mostly about what would happen next in an utterly familiar structure. It was the structure of the fairy tale.

I remember coldly and calculatingly plotting my own when I’d finished reading my way through that pile, and it concerned, from what I remember, an extremely beautiful and incredibly rich young woman plunged into a coma by the machinations of her evil aunt, so she was unconscious through much of the book as a noble young scientist hero fought to bring her back to consciousness and save her family fortune, until he was force to wake her with the Shopping And Fucking equivalent of a kiss. And I never wrote it. I wasn’t cynical enough to write something I didn’t believe, and if I was going to rewrite “Sleeping Beauty,” I was sure I could find another way to do it.

But story privileged is a good thing for me. I care about story. I’m always painfully certain that I’m not really much good at story. I’m always happy when a story feels right, especially when they feel inevitable, when they come out properly. I love beautiful writing, although I’m never convinced that what the English think of as beautiful writing (which is writing that’s clean and straightforward as possible) is what the Americans think of as beautiful writing. And it’s definitely what the Indians think of as beautiful writing, or the Irish think of as beautiful writing, which are other things entirely. But I digress.

I love the drive and shape of story. As I get older, I’m more comfortable with genre. I’m more comfortable deciding what points a reader would feel cheated without. But still my main impulse in writing is to treat myself as the audience, to entertain an audience just like me, who like what I like. That way in a worst case scenario one person enjoyed it.

People ask me what I mean by story. It’s the kind of thing that you get asked and you ponder a lot. And I got it down to my favorite definition. I made a very very long definition then would cross bits out, work it down. And I got it down to “anything that keeps somebody watching, or reading, and then doesn’t leave them feeling cheated at the end.” That’s my definition.

Henry Jenkins: As we’d been getting ready to do this event, I’ve talked to a variety of people, many of whom said the event’s likely to attract multiple constituencies who’ve become interested in your work through the years. Some will know you primarily from your comics like Sandman and some will know you primarily from your prose fiction. And perhaps there are now a few who know you primarily through your TV and film work.

Neil Gaiman: Don’t forget the blog. There’s people who never read a word that I’ve written that just like the blog.

Jenkins: The blog’s amazing.

Gaiman: They want to know how the bees are doing.

Jenkins: So what would each of those groups have missed if they only knew you through a single medium?

Gaiman: In a lot of cases, they’d miss the good stuff. It’s very hard for me to explain to people who are incredibly proud of having read every word that I’ve written and love it and think it’s great that actually, they should read Sandman. It’s really good. They’d like it. And they explain that no, they don’t read comics. And it’s like, “No, read it. You will get the same kind of peculiar buzz that you get from the fiction.” And vice versa.

Probably the one that I hope people don’t miss is the children’s stuff, because I think some of the best stuff is in the children’s fiction. Incredibly proud of The Day I Swapped My Dad for Two Goldfish, of The Wolves in the Walls. I think Coraline is one of the coolest things I’ve done. I think The Graveyard Book is probably the best thing I’ve written. And there’s that weird kind of knowledge that a large adult constituency will not pick up The Graveyard Book because it will be published as a children’s book.

Jenkins: A high percentage of your work has either been written for children or about children. What is it that has drawn you so consistently to children both as a theme and as an audience?

Gaiman: Partly it was having them. I definitely started writing about the point where I was a fairly young father of a very very young son. Violent Cases, I think, was the first thing I wrote that was any good and sounded like me. And a lot of Violent Cases came out of having a three year-old son and remembering what it was like to be three, and seeing things from different angles and trying to explore the nature of memory. So definitely having kids around is part of it.

Also, I used to get really really irritated as a kid reading kids’ fiction with kids in it, where I’d go, “We’re not like this. What have you been drinking? This is weird.” You’d read these books, and you’d go, “You must’ve been a child. By definition, if you are an adult… How can you have forgotten so completely what it’s like? It’s nothing like this.” And occasionally, most of the time that would be aimed at really irritating, bad— The kind of writers who wrote down to you. I remember reading Dandelion Wine by Ray Bradbury, which was a book I loved, and then you get to this chapter about this kid who’ll do anything to get these sneakers in which he can run forever, and I’m reading it going, “This is bollocks. I’m twelve. I don’t want a pair of sneakers I can run forever. Hey, anyone around here, you’re all twelve. Anyone want sneakers you run forever?” And everyone’s going, “No [mumbling].”

“Anyone here who would actually do a job to get the joy of wearing sneakers that would be enough to keep you running all over Waukegan, Illinois delivering things because you got sneakers?” And everyone’s going, “No…sounds a bit weird.” Terrible of me. But mostly, it was a determination at that age not to let that go. A determination to remember. A determination if I ever got to be a writer, to write about that, too.

Jenkins: Many other critics have observed this kind of darkness in your children’s fiction, but in fact the best children’s fiction has always been incredibly dark. We tell stories at bedtime to kids to scare them to death and then to reassure them that it’s not going to happen to them.

Gaiman: I think kids are lot crueler than adults. You discover that when you start talking to kids, telling them stories. They want the bad people to die. Preferably in pain. You don’t want to get into a story with a bad queen or an evil wizard and say, “And then he died in his sleep.” It’s like, “No!” Adults, we are fallen in nature, we are forgiving, we can see our own imperfections, we do not demand painful justice. Kids do. I think that’s part of it.

I actually hadn’t realized that my kid’s stuff was darker than my adult stuff until Kim Newman pointed it out in a review in the Independent of Anansi Boys. He said “this is one Neil Gaiman’s adult novels, which means it’s much lighter in tone.” And I thought, “My God, he’s got a point there.”

And the first three pages of The Graveyard Book is probably the scariest thing I’ve ever written. Not a sensible commercial move. I’m going to make this very very clear. If you want to worry your publisher, write a children’s book with three— Make the first three pages a man with a knife walking around a house in the dark. There were four people living there, two parents, a child, a little toddler. He’s dealt with all of them except the toddler. He’s walking up the stairs.

If you’re going to write a scene like that, what I figured out I should’ve done is slide that in and just make the first scene all about flowers or something. Then parents or teachers who would pick it up and say, “I wonder what’s on the first page,” would go oh, it’s flowers.

As it is, the first line’s “There was a hand in the darkness, and it held a knife.” It never gets that bad again. Kids don’t mind it.

Jenkins: In preparing this, I ran across the quote from you that says, “We have the right and the obligation to tell old stories in our own ways because they are our stories.” I’m wondering in what sense that’s a right and in what sense it’s an obligation.

Gaiman: I think it’s a bit of both. I think if you’re a writer, you want to try and leave things a little different to the way you found them. You want to try and leave stuff behind. And part of that is the idea that you’re allowed to pick up the stuff from the back shelves that has got dusty and people aren’t looking at it anymore, and just buff it up and move it to the front again. It’s not necessarily an act of creation, it’s much more…sometimes just act of saying this is a really good thing and everybody’s forgotten about it. Or, saying this is a really interesting thing and nobody’s looking at it from this angle.

I remember the very very strange feeling I got reading— I was lying in the bath reading Neil Phillips’ Penguin Book of English Folktales. And mostly reading it for new and interesting and odd little folk stories, and then I get to something that’s a retelling of “Snow White.” And I’d read the story of “Snow White.” This is Snow White and robbers, not Snow White and dwarves, but it was the same story. And she’s eaten the apple, she’s unconscious, she’s believed dead, they put her in a glass coffin, prince rides up and says, “I’m in love. I must have her. I must take her back to my castle.” And I thought, what kind of a prince, what kind of a person, says, “Oh, look at this beautiful corpse? I’m taking it back to my castle with me.”

And once you’ve thought that, the next thing that happens is she coughs up the apple and she’s alive again. And I thought, what kind of person has skin as white as snow and lips as red as blood and hair as black as coal and gets to lie in a coffin for six months or whatever and then get up? I’m going, “This is a really peculiar story, actually.” And it was that lovely moment of going, “It’s “Snow White” and why don’t I just retell the story of “Snow White” from the point of view of the wicked queen in which we learn that she wasn’t wicked at all. She just never went far enough?” and make her story about the way that stories are told by the survivors? Stories are told by the winners. And it was enormous fun.

But what made it odder was going, you know that story, people have been tripping over it for years. It’s probably the first, maybe the second story I remember learning. And you don’t inspect it. And then I just sort of looked at it from an odd angle and inspected it, thought it would be a really good thing to retell, and did.

Jenkins: Are there stories that shouldn’t be retold? I don’t mean the 90% that Sturgeon’s talking about, but I mean stories either that are so well-told the first time, that we simply want to leave them lie, or stories that are sacred that we don’t want to meddle with, or for whatever reason.

Gaiman: No, I don’t think there are. I probably would’ve given you a slightly different answer a few weeks ago. But one of the things that I stumbled over when I was in Australia was a graphic novel adaptation of The Great Gatsby by Nicki Greenberg, in which Gatsby is a seahorse and Daisy—I’m not entirely sure what Daisy is, she seems to have a sort of head that’s maybe a puffball. She could be some kind of flower or maybe a bird, or maybe a kind of rather pretty mushroom. You’re not quite sure. And her husband is apparently a troll. It’s a completely straight retelling of Gatsby, done with this amazing cast of grotesques which somehow manages to be so much— Why would it be more moving that Jay Gatsby’s a seahorse? It does not make sense, and if they ever sort out the copyright problems and actually allow it to be sold over here, I think that would be a wonderful thing.

I think my answer to that question would’ve been different pre reading Gatsby, because I would’ve said, “Well, I think there are stories that you shouldn’t…” Now it’s like, “Nah.” Retell it. Use seahorses. It’s brilliant.

Jenkins: You raise the villain in the piece, which is at least sometimes copyright, right? How do we reconcile our right to tell our stories with a world certain characters, Miracleman among them, gets tied up with copyright issues for extended periods of time.

Gaiman: You cope. I don’t know. It’s a balancing act. On the one hand, I love copyright. Copyright’s great. Copyright is what puts food on my table. There is nothing more joyful, as an author, than receiving a check from somewhere like Indonesia for the rights to a translated and published book that you wrote 15 years ago. And look, here’s $600 I didn’t earn. It’s the best thing in the world. I get checks now coming in from countries I didn’t know exist. Sometimes I get copies of books. I have to go on the Internet, typing out words that appear on what seems to be the copyright page to try and figure out, as I desperately Google, what tiny Middle-European country this was actually published in. It’s wonderful.

On the other hand, I think that there’s definitely copyright stuff that has been pushed as far as it gets pushed. And I think there’s places where the concept of Fair Use is one that it’s too easy for it to get eroded. And I think it needs to be vigilantly patrolled. I’m really wishy-washy on the whole copyright thing. I’m absolutely rubbish. Because on the one hand, and then on the other. But I do think that you should be allowed to do things that are transformative. The Jungle Book is still in copyright. It was out of copyright back in the mid-80s for a couple of years.

There was a little period, copyright was originally death plus 50 years, and then they made it death plus 75 years. A lot of books that had wandered out of copyright just leapt back into copyright again. But The Graveyeard Book is absolutely inspired by the central idea of The Jungle Book, and it’s almost like a dialogue with it in some places.

It’s the oldest idea I’ve ever had. I was 25, something like that. The oldest idea that I’ve had that I hadn’t used. There were ideas I had as a kid that I wound up using on The Sandman, but I was about 25 and we lived in a very tall, spindly house over the road from a graveyard, and we didn’t have a garden. So when my son Mike needed to ride his little tricycle, I would take him down the stairs and over the road into the graveyard, and I’d sit and read on a bench and he would ride his tricycle between the gravestones, very happily. And one day, I just remember looking at him and going, “You know, The Jungle Book was all about a kid whose family were killed and got adopted by wild animals, raised in the jungle by jungle animals, taught the things that jungle animals know. I could do a book about a little kid whose family are killed, wanders into a graveyard and is adopted by dead people, and taught all the things that dead people know.”

And it was this immediate point of going okay, well if I did that then my Bagheera character, the black panther, would be a vampire. And I’d probably have a werewolf in it as my Baloo, and that would work. All of this stuff sort of clicked, and when I wrote the book, there were a couple of stories that are directly bouncing off. One of my favorite stories in The Jungle Book itself is the one where Mowgli is taken away by the apes, or the monkeys kidnap him. And I thought I’d do one like that, only they’ll be little ghouls. So these strange little ghouls kidnap him and they call each other the Duke of Westminster, the Bishop of Bath and Wells, and the Honorable Archibald Westgate, and they… There are more ghouls, actually you meet more. You meet the 33rd President of the United States. After a while you figure out they aren’t actually those people, they just got to name themselves after whatever they ate first after becoming a ghoul.

Jenkins: Many of your stories repurpose and expand upon themes from classical mythology, folk tales, and fairy tales, we’ve already alluded to. What writers about those themes have informed your work? Joseph Campbell, Robert Darnton, or…?

Gaiman: No, actually. Joseph Campbell is one of the very few writers who I gave up on intentionally. [I] quite enjoyed the first couple of the Masks of God, which weren’t really about mythology, but when I got to The Hero with a Thousand Faces, I got about 20 pages into it, I thought, “I shouldn’t be reading this.” This is like a schematic for how these things should work. This is wrong. If I’m doing my job, it’ll work like this anyway.

Mostly it’s primary sources, wherever you can. I mean, the people who got me addicted to myth would’ve been people like, there was an English writer called Roger Lancelyn Green who wrote books with titles like Tales of the Norsemen and Tales of Ancient Egypt. The kind of stuff that you’d pick up as a kid.

I love myth. Wherever I’d be, going around the world, I’d always pick up local books of myths, figuring they’ll probably be slightly more likely to be closer to primary sources. But I’m really rotten at reading what people have written about myths. I just like reading myths.

Jenkins: Are there mythologies in the world today that we’ve undermined, that you think would be rich sources for future stories?

Gaiman: I think there are definitely a few myths that we’ve sort of lost, which I think is really sad. When I was researching American Gods, I fell in love with the sort of Eastern European/Russian stuff. I put Czernobog and The Zorya in there, and found just one book on myth which had a little chapter on them and determined to go out and find all the rest of it, because obviously there was so much more. And after about six months of writing letters to people and going to libraries, I realized that there wasn’t really that much more. You had an incredibly efficient Eastern church who got rid of a lot of this stuff, and you had nice people like Napoleon busily burning things as he marched to or from Moscow, and we don’t really have much. Which was rather sad, because it looked like there was something just as interesting and just as odd as we’ve got in Norse.

But then again we’ve only got Norse more or less by accident. There are very few manuscripts that’ve survived, and there are probably huge quantities of Norse mythology lost. Norse is the one I always keep coming back to as well. I just love how deeply, utterly fucked up on every level… The Romans and the Greeks were alright. They’re busily running around and getting laid and turning people into flowers… The Norse, they’re cold, they’re miserable, they’re grumpy, and it’s all going to end in tears and death. And in the meantime, let’s get drunk. It’s great.

Jenkins: One of the things that I always love about your stories is the way you brush up against mythical themes and very mundane details of our everyday life. I’ve often wondered if that’s partially a product of trying to immerse a world that sees itself in highly rational terms, that doesn’t believe in magic, often is post-secular, with this kind of mythology that comes out of a world where people did believe the mythical figures were all around them and maybe they want to hold them at bay. But they saw the world as a magical place, so is there a challenge in writing such stories for today’s society?

Gaiman: No, it’s fun. You do it for different reasons, though. There are completely different reasons why you’ll go off and decide you need to yank a myth and drag it over and polish it up and do something with it. In American Gods, I’d been living in America for I think about seven, eight years. I was very puzzled by it. I thought it was a really interesting place that bore much less resemblance to the America that I’d seen on the movies than I was expecting. And it was filled with odd little bits off at the side that I didn’t quite understand. And I was very puzzled by things like the way that people’s relationship with their homeland as immigrants, and the way that America seemed to treat other cultures. In England, if you got Poles coming into England, or Italians, they were very Polish or they’d be very Italian, and that would continue. In America you got the feeling that that was… I would run into people who there was no sense of continuity. Maybe some food, maybe something.

Then I ran into a quote by Richard Dawson, the folklorist. It was just this odd little quote where he was talking about the fact that there was no magic. The old people who he would go around and interview would tell stories about fairies or about magic, but they would set those stories in Greece or wherever they came from. And when he would ask, “Well, what about America?” they’d say that stuff doesn’t cross the seas. It didn’t come here.

That kind of went into, I was reading a lot of the Jack stories at the time, the Appalachian Jack stories, which are these stories that came from England with the first settlers, they moved into the Appalachian. They kept telling these stories long after they’d stopped being told in England, which meant that folklorists could go around in the 1920s and 30s and collect them. And what’s really odd is the magic had gone. You’d get stories that in England were all about giants or witches or Jack doing something very clever, which would involve some magic, and the American version would just be about him doing something quick-witted, without magic. You’d still have kings in there, although they would keep explaining the king was just a man who had a big house, which I loved. And the kings would still have beautiful daughters, but the magic had gone.

I was pondering that, and trying to ponder if there was some way out of that, and something I could do with that, something I could use to tell a story. I was incredibly tired. I had to go to Norway to sign some books, as one does. My travel agent at the time said, “Did you know you can stop over in Iceland for 24 hours for nothing, if you fly Iceland Air from Minneapolis.” I said I didn’t know that. (It’s not the kind of thing you know.) So I got the plane. It was July 2nd, 3rd, 4th, somewhere around there. I flew to Reykjavik, got off at Reykjavik airport. It was 6:30 in the morning. It’s a very very short flight, because you just nip over the pole. I left at seven o’clock that evening, it was now midnight but now it’s six o’clock in the morning, and I thought I’ll just keep going til it goes dark, then.

So it’s three o’clock that morning. It is still daylight. There are incredibly thin, white curtains. My body is going, “I’ve no idea what you’re doing. We’ll just keep going.” There is no sleep, of any kind. Around mid-day the following day, it’s Sunday. I’m walking around Reykjavik, I pass the only sushi restaurant in Reykjavik, and notice in my sleepless delirium that they have what appears to be pony sushi and I’m very glad that it’s closed. I wander into a tourist display, and the tourist display shows the little map of the voyages out to Newfoundland to found the Viking colonies, and I thought “Gee, I wonder if they took their gods with them.”

And all of a sudden, everything that I’d been pondering just fell into place and I had a story. And I thought I can absolutely talk about the immigrant experience, I can talk about what it’s like to leave cultures behind, I can talk about America, I can talk about all this stuff that I don’t understand like why people go to see the second-largest ball of twine in Illinois. I can put it all in here. And I did. Mythology became a wonderful tool at that point.

Jenkins: We both began by paying tribute to Julius Schwartz, and one form of American mythology is the superhero.

Gaiman: Absolutely.

Jenkins: What do you think about that Silver Age period has proven so fertile to subsequent generations of writers? What emerged then about the figure of the superhero that makes it a rich resource for us today?

Gaiman: I think what Julie did was absolutely fascinating. Without Julie and without Stan Lee, probably without Jack Kirby as well, there would be no superheroes today. What Julie did was reinvent them, and reinvent them very cleanly and simply. The DC universe was a very odd sort of place. It was really good if you were in England, and you were about 8, maybe 9, 11, 12, somewhere around there. The reason why it was really good was because they pressed the reset button at the end of every comic. At the end of every story, you reset. So you really only had to know who Batman was, and you would get a full Batman story, which if your comics are coming across as ballast in boats and you’ve got Batman #171 and the next one you’re going to see is Batman #183 is really good.

Stan Lee…bit problematic. People would keep swinging off and you’d have a little thing at the bottom saying “Continued in Daredevil #36 —Smiling Stan” and you would know your chances of ever seeing Daredevil #36 were right up there with your chances of your seeing a unicorn. That has absolutely nothing to do with Julie Schwartz, I just wanted to throw it in.

You people, who had proper newsstands, you didn’t know how lucky you were. We didn’t have direct market comic shops back then. We had to carve our comics on the side of a brontosaurus.

Actually what was really interesting is what Julie did was very different for each of the things he did. He took a science fiction sensibility, first of all, and infused that in. You’ve got the whole Mystery in Space, Adam Strange, you’ve got a Green Lantern who was an absolutely brilliant ripping off of E.E. “Doc” Smith’s Lensman series. (Talk about the interestingness of copyright.) And actually in many ways were better, and cleaner. But it was taking that idea, you would take a standard science fiction idea. Making the Flash much more a science hero, these wonderful clean Carmine Infantino lines. You got the very clean SF influence on the early Silver Age.

You get the Justice League. The way that Julie told me, he said the guy who ran DC Comics was incredibly pleased with the orders on Justice League #1. He played golf with Martin Goodman, who owned Marvel and was more or less ready to shut the whole thing down, and bragged to Martin Goodman about Justice League, and Martin Goodman went into the offices and told Stan, “Superhero team, it’s working for DC.” And Stan spoke to Jack Kirby and they came up with The Fantastic Four. That was how Julie told it, and wherever it’s Julie Schwartz’ word against the truth, I always go with Julie, anyway.

Jenkins: As John Ford said, “Print the legend.”

Gaiman: Absolutely. I got into trouble once with that on an introduction to an H.P. Lovecraft collection. Because Julie had bragged to me several times that he sold At the Mountains of Madness to Astounding Science Fiction and it was the only sale that H.P. Lovecraft had made that wasn’t to Weird Tales or to the lesser pulps. So I put this in my introduction and one of the many H.P. Lovecraft scholars explained that this was rubbish. I’m going, “But Julie told me! It has to be true. It’s better than true. It’s Julie.”

Jenkins: You mentioned Jack Kirby a minute ago and you’ve recently revisited some of his fiction with The Eternals. What did you find interesting about the Jack Kirby world?

Gaiman: Last time I said this, I got people online, John Byrne or somebody completely misunderstanding what I’d said and writing screeds online about how dare I compare myself to Jack Kirby and stuff like that. What I loved about The Eternals was that it wasn’t top-notch Kirby. It was problematic Kirby. I would have had no interest in doing something like The New Gods, which I think is perfect. Why would you mess with it?

The Eternals had problems, and a lot of the problems were actually problems that I then found when I started trying to write it. But The Eternals was also something I did to a brief, and it was a very specific brief. It was Joe Quesada saying to me, “Neil, do you remember The Eternals?” And I said, “Yes. How could you forget something in which Ikaris goes under the nom de plume of ‘Ike Harris?’ ” Great Kirby names.

And he said, “We don’t really know what they are. They’re part of the Marvel Universe but they’re not really. They’ve been off to one side, and we want to try and do a thing where we have the mutants and we have the heroes and we have the Eternals. Can you just sort of bring them back and clean them off and plug them in?”

So I went back and reread all the Jack Kirby stuff, and you could feel Jack’s frustration. You could feel Jack’s frustration because he obviously had come up with this wonderful idea which is, okay I’m doing Chariots of the Gods? and the idea is these are the characters who inspired the legends of the gods. Which means by definition they can’t really be part of the Marvel Universe, because how can you have the characters who inspired the legends of Thor or Hercules in a universe where you’ve got Thor and Hercules wandering around? It is a bit problematic, to say the least.

And you’d watch Jack obviously getting orders to make this more part of the Marvel Universe, his ways of trying to get ’round it. There’s one which as The Incredible Hulk on the cover, but then you discover that it’s not actually The Incredible Hulk. It’s a robotic, cheerleading mascot of The Incredible Hulk that then goes wild and does all the things the Hulk does.

I loved it, but you could taste Jack’s frustration. He’d come back to do something and people were pushing him around, and it didn’t end… Obviously it was going somewhere and suddenly it just stops. It actually seemed like a really interesting project to go okay, well this thing was not built to be part of the Marvel Universe. I wonder if I can unscrew it, clean it off, polish it up, plug it back in, and see if I can get it to work as part of the Marvel Universe.

Jenkins: Recently a number of people have begun playing around with the Sandman mythology that you helped to create. What has that experience been like, to watch other people monkey with your stories?

Gaiman: It’s hard. A lot of the time it’s like watching your kids go off to college. They come back with nose rings, then the next time you see them they’ve got a lip ring. And then you’re going “not a facial tattoo, dear God, not a facial tattoo.”

Mostly I like it. DC Comics and I drew some early lines in the sand a decade ago when I finished with Sandman. I said, “Look, all of this stuff you can play with. You can play with anything that existed before I started that I dragged in. That’s all yours, anyway. And you can play with this, this, this, and this. And furthermore, I think something like this would be great.” It took me about five years to persuade them to do a Lucifer comic. I kept saying, “I think he’s really good. I think he could do a spin-off.”

They said, “Well, we’re not sure.”

“No, he could.”

And Mike Carey did the Lucifer comic and it was wonderful. I loved it. That was, I think, my favorite of all of them. Just because it wasn’t what I would’ve done. It wasn’t somebody trying to do me, but it was somebody taking a character or character’s background and just going off and having fun with it.

Jenkins: Various writers have described you as creating comic strips for intellectuals, or have noted the literariness of your comics work. This is in some senses a back-handed compliment. They’re treating you as a serious artist only insofar as you break with other comic writers. What do you think or feel about this representation of your work? It seems like while many people who break with paraliterature as it’s been called and move into the mainstream or the slipstream as you talked about earlier, sort of break with their pulp roots. But you seem to thrive on it. You seem to constantly come back to it. So I’m curious about how you see yourself negotiating between high and pop culture in your work.

Gaiman: I guess I feel like I’m from the gutter and I don’t ever want to forget it. And I’m proud of it. And I think there’s an incredible amount of life in the gutter. It was much more fun, Henry, doing comics and coming to universities. Back in about 1996, I think, I was invited by a St. Louis university, and I went out there. The English department boycotted it because I wrote comics. That was so cool. I miss those days.

I’m very impressed when people get away from their pulp roots. I like my pulp roots. And I think possibly that’s because I have a lot roots, and some of them are pulp and some of them aren’t. Kipling is as much part of it as Julie Schwartz, and I wouldn’t put one of those two as more important—well I would, actually. Julie’s more important than Kipling.

But what actually fascinates me now is you’ve got sort of the reverse going on in a few places. Michael Chabon is edging closer and closer. He starts off being incredibly respectable and then you get Kavalier & Clay and it wins the Pulitzer. Now he’s much happier because he’s winning Hugos and Nebulas. Oh, he hasn’t won the Hugo yet, but he’s won the Nebula. He’s up for a Locus Award. I think it’s so cool. I think watching him gradually edging into our camp… It’s nicer here in the pulp world.

Jenkins: Jonathan Lethem’s writing comics.

Gaiman: Jonathan Lethem now doing Omega, yes. It’s lively. The parties are better. Or at least louder.

I think there was probably a period of time, particularly in the 70s/80s when it actually was important for writers to go, “No, I am not a science fiction writer, I am a proper writer.” Or whatever. There was a period in there where the Bradburys and the Ellisons and various others sort of made their bid and staked their claim for literary credibility.

I don’t really care about the literary credibility stuff. I started in comics. That’s so much further down. The first major award I got was the World Fantasy Award, and I was told the day after I got it that they’d changed the award to make sure no more comics got it. I say I was told the day after because I notice there is now a small faction that says, “No no, that never happened.” It’s like, “Did.” [nodding head]

Jenkins: You were part of a generation of comics writers who came from the UK and shook up the American comic scene at a certain point. Why so many British writers all at once? What was in the water over there?

Gaiman: You just took my joke, Henry.

Jenkins: Sorry about that.

Gaiman: No, it’s alright. That was what I was going to say to give me 30 seconds thinking time.

What was it? I think part of it was the strange way these comics turned up. Part of it was how very very different the entire culture was. And part of it was the fact that you had a generation in England who loved American comics, starting out with Alan Moore. You had me, you had Grant Morrisson, loads of us. We loved American comics, and we loved other things, too.

And we didn’t see why you had to keep doing the same things in comics. It just seemed like a wonderful medium that you could do cool things in. I’d wanted to write American comics since I was 12. I’d never, ever wanted to write English comics. I wanted to get my hands on those wonderful Julie Schwartz four-color characters.

And also I think part of it is that Alan Moore set the bar really high. Alan came in and started doing Swamp Thing, did his amazing last Superman story. Did Watchmen. It was a really high bar, but you’re also going, “Oh my gosh, you can do cool stuff.” And that in itself I think was an inspiration for us.

But mostly it was, I don’t know, the right time. We’d grown up in the 60s. We’d watched the Batman TV show. We hadn’t quite understood it. In England, it wasn’t just the death traps. In England, they actually had a film clip filmed especially for the UK in which Adam West and Burt Ward stand there and point out that they can’t fly. Actually Adam West points out that he can’t fly, neither should you, and then Burt Ward goes, “Holy broken bones!”

This was not necessary in America. Nobody in America went, “I’m Batman. I can fly.” For some reason the English, these kids kids jumping out of windows all over the place, off bridges.

Jenkins: It’s clearly all those missing issues that you were talking about.

Gaiman: If only we’d read them.

Jenkins: Shifting gears, you’ve been very active in the Comics Defense Fund. Why do you think comics have proven to be particularly vulnerable to censorship through the years?

Gaiman: Because they’ve got pictures. Because you can take things out of context in comics better than you can with anything else. If you want to show somebody why a book is offensive, you’re going to have to reprint a great big slab of prose. You want to show them why a film is offensive, you have to show it to them.

Comics is brilliant. It even gets down to… Frederic Wertham’s book Seduction of the Innocent has a sequence in it where he actually just takes out individual panels, and probably my favorite of all of the panels is one captioned something like “There are hidden pictures everywhere for those who know how to look for them.” It’s man at a beach in front of a girl who’s also on the beach. And if you sort of squint and turn your head sideways, and have a really really filthy mind, you could sort of imagine that maybe somewhere in the muscle structure of the man’s shoulder, there is some sort of something faintly pubic going on.

It’s a stretch. It’s a very very long stretch, but Frederic Wertham made it, and the truth is that there are a lot of panels you can find that are much less of a stretch. EC comics were particularly vulnerable to this. EC Comics did these wonderful horror comics, particularly in the 50s, and they were deeply moral, and filled with delightful and awful retribution. They were dark and they were wonderful. And you’d just have to take a few panels out of context, and suddenly we’re banning horror comics.

Comics are vulnerable because it’s really easy. Comics these days are still vulnerable because you can still just about, if you are a news reporter on a slow news day, somewhere in a very boring town, you can actually go down to your local comic store, stand in front of the kids’ comics, and say, “You thought that comics were all Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles and Archie, but look what your kids are reading” and then grab something from the adults-only shelf and put it in front of the camera, and you’re away. You’ve got five minutes of “this filth should be put out.”

We just won the Gordon Lee case in Rome, Georgia. Gordon Lee, very nice man, comics retailer. For Halloween, they gave away comics to the kids in the neighborhood for free. Kids walked in, they’d get a comic. This is done by a junior kid on the till. Gordon’s doing the till, junior kid is giving away comics. They checked them through, but not thoroughly enough, and one nine year-old, possibly—actually let’s go with “allegedly at least in one version of the police complaint” because they actually changed it after 18 months. It got a bit puzzling. But, probably, a nine year-old was given a comic that he shouldn’t have been given. It wasn’t a porno comic. It was sort of an anthology title, and one of the stories featured Pablo Picasso in France in the 1920s, painting in the nude. Which is how Pablo Picasso painted, apparently. I didn’t know this. These tiny, weeny little panels of Picasso. This tiny tiny tiny, weeny weeny weeny weeny little Picasso pee-pee.

Now, any sane parent whose kid says, “I’ve got this, this is inappropriate.” would go back to the comic store when it opened the day after Halloween and say, “You guys gave my nine year-old this. This is really not on.” And they would say, “We are terribly sorry. Here is a Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles graphic novel, with our apologies.” and that sort of how these things go. But what this parent did was call the police. And they threw the book at him. This was not just minor offenses, these were felonies, they found obscure Atlanta statutes about nudity, and they went for it. And they were planing to send Gordon to jail.

It took about two and half, three years to get that one sorted out. And they got weirder and weirder… We were a day away from going to trial and the prosecution suddenly announced that all of their evidence was wrong, and that actually the comic hadn’t been given to the nine year-old, it had been given to his five year-old brother. Then the next time we went to trial, which is another seven, eight, nine months later, we finally get back to trial, and the prosecution, who’d been told that there’s stuff that they cannot mention and have agreed that this stuff cannot be mentioned, stand up and in their opening speech mention it. So the judge declares a mistrial and starts it all over again, which apparently they did because they just didn’t like the look of the jury.

So about a month and a half ago, we were up to the point of getting to the next version of the trial, but at this point the DA was coming up for re-election. The editorials pointing out that she was making a laughing stock of Rome, Georgia were starting to get to her, I think. And they agreed that in exchange for an apology from Gordon Lee for giving the kid this book, they would drop all the charges.

Now, the dark side of this is that it cost about $100,000 to get to that point in the American justice system, especially when you have to prepare for three different trials. This is witnesses getting flown in, expert witnesses are coming in to try and point out that your tiny little Picasso pee-pee is not breaking laws. It’s expensive, and so that’s why I do it. But that’s the kind of vulnerability that comics have. The fundamental vulnerability is very very simply just the idea that comics are for kids, and that by doing comics not intended for kids, you are somehow doing something wrong.

Cases like that are the high-profile ones. Right now, as much of what the Comic Book Legal Defense Fund is doing is things like educating librarians. They’re getting calls from librarians all the time saying, “Somebody’s put in a formal library complaint that we have Daredevil on our shelves, or whatever. Somebody’s decided it’s offensive. How can we defend the Frank Miller Daredevil?” So they’re putting together education packets and offering help to librarians, who right now are getting it hardest.

Jenkins: Shifting gears a little bit, many of your works circle around themes of games, toys, dolls, and puppets. What relationship do you see between these childhood playthings and the process of storytelling?

Gaiman: They’re just really sinister, aren’t they?

I’m not sure if I’ve ever seen anything as creepy as an old doll. There may be something, but old dolls, really dusty Victorian ones made with glass eyes and wigs slightly askew with that expression on their face… You put that next to an original, functioning iron maiden, and the doll is creepier. Especially if they’ve got mold going on.

I don’t know. It’s always dangerous, or non-productive, or you get lied to, when you ask a writer about themes. Because the truth is I don’t think we know. I’m not saying it’s all unconscious, but I’m saying that themes pick us as much as we pick them. From the perspective of being a writer, what you’re desperately trying to do each time (or at least for this particular writer) is you’re trying to do something new. You’re trying to do something you haven’t done before. You are desperately trying not to repeat yourself. You’re convinced that whatever you’re doing next is absolutely and utterly different from anything else you’ve ever done. And then you do it. And then people come along and point out how exactly and precisely it lines up with everything you’ve ever done, and they point to all the common themes.

I remember once, somebody asked me about the kiss that would occur in my books three-quarters of the way through to indicate that we were now moving into Act 3. And I said, “What?”

And they said, “Well you must be conscious, you do it every time.”

“What?”

“There’s always a kiss. Rarely sexual, it’s sort of a not-sexual kiss.”

And I’m going, “Okay, well I’ll make sure I don’t do that ever again.” At the time, I was finishing off American Gods and I handed it in, and I’m sitting there rereading it very proudly, and suddenly there’s this completely asexual kiss between Shadow and Sam, and they’re kissing in the pub, and we’re now into Act 3, and it’s like, “Oh, bugger.”

Jenkins: I will try to avoid falling into the trap of interpreting your work.

Gaiman: But actually what I was saying right at the beginning of the speech— I think it’s completely fair game for anybody to interpret the work. And I also think it’s completely— I am not a writer who believes that my point of view about something that I’ve done is necessarily right. Obviously I’ve probably thought about it longer and harder than you have. But I could be wrong, and I think sometimes I am. I will always try and correct people on matters of fact if they say, “I’ve done my PhD on you. Here you go.” I will go through and say, “That issue was actually published before that one so it can’t have influenced that” or whatever.

But beyond that, once it’s published I figure absolutely anybody has as much right to an opinion about it as I do. That I’m the person who wrote it doesn’t necessarily privilege my opinion.

Although obviously really it does.

Jenkins: Given the apparent persistence of games as a theme in your work, it’s curious that that’s the one medium so far at least that you haven’t worked within.

Gaiman: That wasn’t really intentional. It had more to do with my slow-growing conviction that I was a Jonah. The first time I was ever approached to do a game was about 1986⁄87, and Kim Newman and I were approached by this guy to do a game and we came up with this game. It was text games at the time, and the whole thing was you woke up in a hotel room, and if memory serves you needed to figure out (you had no memory) that you were a bomb. And actually there was no way that you couldn’t not explode and die. But if you did it in the right place, the right time, you could actually win the game. We came up with that and we did the whole thing, and we handed it in, and the people went out of business.

At the time, I thought nothing of it, until 1991-ish when I did the Alice Cooper project The Last Temptation, and was asked if we’d do a game to go along with it, and worked on a game. Did about a week’s worth of work for a game that was going to go along and get released with it. And watched as the company went out of business.

During the 90s, companies would approach DC Comics and buy the rights to Sandman, which they would plan to do as a game, and I would come in as a consultant. And they’d go out of business.

By the end of the 90s, everybody had gone out of business that I’d ever been involved with on a gaming basis. Nobody had ever stuck around long enough to pay me. So although I had spent many happy weeks in hotel rooms and offices plotting things, I’d never been paid— Actually I did sort of get paid once. I got a phone call from a company, the very first thing they were going to do was give me a new notebook computer. And I got a phone call from this guy saying, “Just letting you know, we’re going out of business and tomorrow the official receiver’s coming in to lock the doors and shut us down. But I have your computer on my desk so I’m about to post it to you and lose all documentation on it. If anybody asks you, we never had this conversation.” So I did actually get a notebook computer.

So at the end of the 90s I thought I am bad luck. I destroy… All I have to do is say, “Yes, I will be part of this thing” and they’d go out of business. And I retired from the business of not making computer games at that point. Maybe I will one day return to the business of not making computer games, causing otherwise harmless companies to go out of business.

Jenkins: Many American farmers have lived for years off not growing crops, so it’s… This event would not have been possible without Gene Fierro and Geoff Long. Geoff sent me a question that sort of grew out of his thesis research, and I thought I’d read it and get a response for him.

One of the things that makes Sandman work so well is its artful deployment of negative capability, the constant use of characters and events outside the central narrative that keep readers guessing about what your characters are talking about. How much of this is intentionally planned? Was this planned out from the beginning, or added as you went along? Where did you pick up this technique? And are we ever going to find out how Delight became Delirium?

Gaiman: I like the way he slides that last question in. I don’t know. To be honest, it depends a lot on DC Comics. I would love to get together with Jill Thompson and do that story, but whether or not it will happen is much more to do— I thought we were probably going to do that or something like it for Sandman’s 20th anniversary, but it was impossible to get the behind-the-scenes stuff to come together. Is that suitably cryptic?

Jenkins: About negative capability more generally…

Gaiman: There we go. Yes. Anything to avoid talking about contracts with DC Comics.

Was it intentional from the beginning? No. But it became fairly apparently fairly quickly in Sandman that I was writing a story in which I was going to have 12 issues a year to tell a big, overarching story that was going— I didn’t quite know how long it was going to take, but I knew the shape of the story I was telling. Sort of like if you set out in Boston and you’re going to hitchhike to Manhattan. You know the shape of the journey, you don’t know everything that’s going to happen on the way, and you don’t really know how long it’s going to take.

So I’m writing Sandman, and really while I’m on the way I figure out for myself that if I keep him off-stage sometimes, if he becomes negative space, if people are talking about him, if we see the impact of what he has and does, you get to see him from a completely different angle. As long as you’re inside his head looking out, you’re seeing things one way, but he became so much more, for want of a better word, mythic. Also more important, when he was off.

When Geoff asked me this very same question in the taxi on the way from the airport to the hotel, in the manner of somebody who has a thesis to write and is going to make damn sure his question gets asked and is not going to rely on Henry to ask it for him in front of an audience of 1,200 people, I tried to say look, when you’re doing something at that scale, it’s almost like drawing a character. You can draw a picture of Morpheus, and then cut it up into little squares. He’s not going to be in every square. Some squares are just going to be corners. Some might just have a bit of foot in. But the overall thing that you’re doing is always describing this character, whether he’s on or off.

And that was really how I felt about it when I was writing it. There was definitely the knowledge that a storyline like “Game of You,” in which he’s barely on, and when he is it’s pretty much as a god would contrast really nicely with something like “Brief Lives,” where we’re down at his level being driven across America looking for his brother. And it was much more intuitive. It’s the kind of thing that you definitely don’t sit down there— You would have to be mad and some kind of egomaniac to sit down in 1987 and go, “Right, I’m going to do this whole thing, and I will have these comics which there will be negative space there and the character will be defined by his absence, ha ha.”

What you’re sitting and thinking in 1987 is, “Okay. So. I think I’m writing something that will probably be a minor critical success, which means it will be a completely commercial failure. The way that DC are currently behaving is they give everything a year so as not to lose face. Which means I get 12 issues. Which means the call that will come in cancelling me will be at issue #8. So what I need to do is plot out the first 8 issues so that’ll be a story arc, so when they phone me at issue #8 to say that we’re cancelled and they’re running to issue #12, I can do four short stories and then we’ll finish up there.”

So that’s about what you’re thinking when you start out, and everything else that you’re building in, all the grandiose and bizarre plans that you have for the end of this thing, are just that. They’re bizarre, grandiose plans that you’re not even— Some of them you’re admitting to yourself, none of them are you telling your editor. And then you get to issue #8 and it’s selling more than anything of its kind has sold before and they aren’t cancelling you. So then you start going, “Okay. I think I can do this thing now.” And you’re going I have this storyline which at the time in my head was called “Suppose They Gave an Inferno and Nobody Came” but in the end I called it “Season of Mists.”

I thought, “Everyone’s going to love that one, so I’m not going to do that next. I’m going to do this other stuff next that they won’t love as much. But that’ll give me this thing” and you’re sort of working out things in a really strange kind of way in order to get to the end. It was another couple of years before I idly started saying in conversation to my editor and then to the publisher of DC, I would say things like, “You know, I was thinking it might be a really good idea if Sandman finished when I was done, and you didn’t get another writer in.”

And they would say things to me like, “Neil… You know that’s not what happens in comics. When it’s done, it’ll be Paul Kupperbeg’s turn” or whatever.

And I’m going, “Well, but [indistinct noises]” And then I didn’t mention that again to them. But in interviews over the next few years, I would casually say when asked what would happen in Sandman, “Well, I hope it finishes when I finish, because otherwise I’ll never work for DC again.”

And somewhere in there, we’re 18 months/2 years before the end, I get a phone call from Karen my editor saying, “You know, we’ve been thinking. We can’t carry on after you’ve left, can we?”

I said, “No.”

And she’d say, “You are planning to finish the story.”

I said, “Yeah.”

She said, “Well, maybe we could do a spin-off and call it The Dreaming.”

I said, “What a good idea.”

There’s a level on which you have to— You’re playing an incredibly complicated game when you’re doing a monthly comic that runs over seven, eight years and is all telling one story. And honestly I’ve been spoiled now, going off and doing novels. Novels are magic. There’s this thing you can do with novels where if you’re on the last chapter and you have a really good idea for something that you could set up in the first chapter, you just go back and set it up. Nobody knows.

In comics, if you have a really good idea for something that you’ve set up in the last chapter and it wasn’t in the first chapter, people have owned it for five years. You can’t sneak back and draw something in to everybody’s comic, much as you’d love to. If that gun wasn’t in the drawer… So you had to sort of put it in. And sometimes you’d put it in knowing what it meant, and sometimes you wouldn’t.

Reading Dickens, always very odd for me because I’ll read Dickens and my Sandman head, my little Sandman brain starts clicking and whirring, and little lights start flashing because Dickens was writing serially and couldn’t go back and do anything. And I will read him going, “Okay, that’s part of your plot. That’s something that you don’t know what it is, but it’ll be useful later. That’s something that you think is just a way to pull two pages together but I bet you’ll find you actually needed that.”

Which is the really weird thing about writing. At some point in a story, you’ve always built something, that sort of really oddly-shaped wrench, and you’re not even sure why you put it in. You thought it was just for fun, and then three-quarters of the way through the story you’ll go, “I’m really in trouble here. If only I had a really oddly-sha—oh!”

But it is that feeling with reading Dickens of going okay, I know what you’re doing here. This is part of your overall story, this is stuff that you’re doing to entertain yourself, this is going to be useful, this is a ball in the air and you’re going “it will come down later” and you’re not quite sure when but you know that it will.

Jenkins: Thanks so much for everyone coming, and thanks to Neil, and thanks to Gene and Geoff.