Kevin Slavin: Alright. So we’ll kick this off. I know people keep coming in, because that’s that’s what we do here. I’ll start by introducing Warren. I know probably a lot of you saw him yesterday. but just to make clear. So, Warren was born in Australia, lives in Paris with his wife and two children. Studied violin and flute, and went on to become a member of several groups, Dirty Three, Nick Cave and the Bad Seeds and Grinderman. He’s also composed film scores with Nick Cave, plays violin, piano, guitar, flute, mandolin, tenor guitar, and viola. Been a member of Nick Cave and the Bad Seeds…

Sorry, wrong Warren Ellis.

Warren Ellis: Yeah.

Slavin: Warren Ellis is an English comic book writer, novelist, and screenwriter. That’s you.

Ellis: … Yeah.

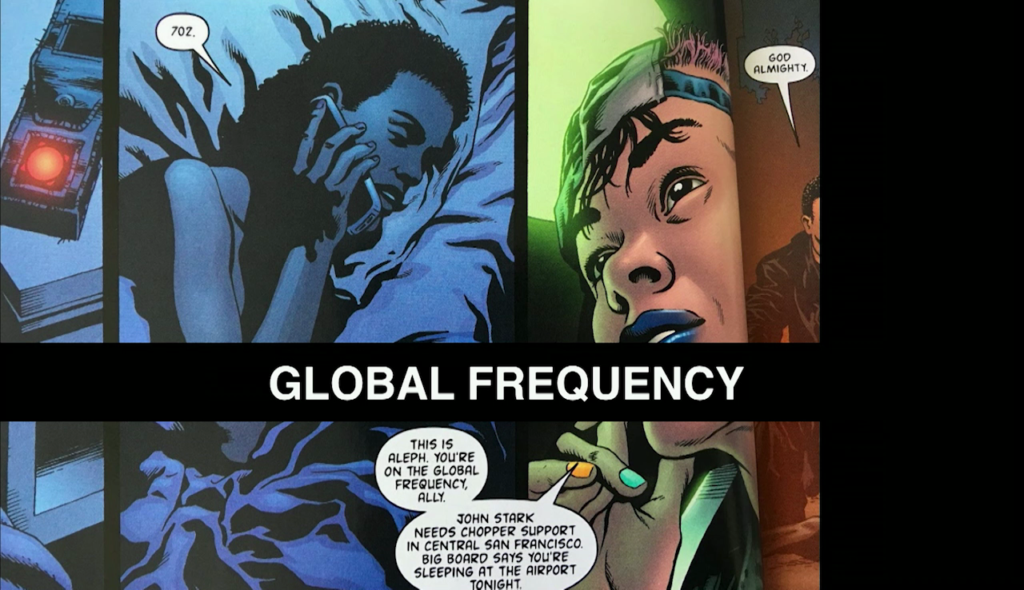

Slavin: Yeah. Okay. Best known as the cocreator of several original comics series, including Transmetropolitan, Global Frequency, Red (adapted as the feature film Red), Trees, Injection… I have some images from all those. We’ll be talking about all these. Also the author of the novels Crooked Little Vein, Gun Machine, and very recently, Normal. Also a lot of other stuff that we’ll talk about. But it’s a big deal to have you here. I’m really excited about it. And I think it’s a very necessary kind of counterpart to, I think, what the Media Lab already has and is good at.

I think the role of stories and narratives and the ability to funnel imagination into stories isn’t superbly well-represented at the Lab, and it’s becoming increasingly important. And I think having an hour for us to be able to sit with you and sort of think about and learn about some of the ways that you think about this is really really valuable to whatever it is that anybody is doing.

So, trigger warnings include powerful swear words to come, ebola—which comes up frequently in your work, a couple of people get burned to death in some of these slides, cosmology, and some politics. So if any of those offend you—or you, really—

Ellis: I’m way past the point where anything offends me at this point.

Slavin: Yeah, okay. That’s… Okay, great. So I want to just talk for one minute about stories and their role in our lives. Because I think it’s really easy to kind of to give— Oh, and I should add that normally this formats, the conversations format, is usually three people. And since we’re only two, the third will be played by the role of…

Ellis: Tom.

Slavin: Tom. So. To Tom. [raises glass]

Ellis: Cheers, Tom.

Slavin: Cheers, Tom. Okay.

Ellis: Sorry, if they’re going to ask me questions at this time of day I need anesthetic. This is my morning.

Slavin: It’s medical.

Ellis: Yes.

Slavin: Okay. So look. Whatever it is that you’re working on, it’s easy to kind of give the inappropriate weight to the science or the technology of it. And I think that if we look—especially in 2017, but this has always been the case—whatever science or technology that you’re thinking about—whether it’s stem cells or vaccines or just anything around human health, these things are being dictated, at least in the United States at the moment, much more by stories than by science. And let’s be very honest and clear about that. That all the science and technology is only going to go as far as the stories that can transmit that in a capable and meaningful way. And that’s why—you know, I think a lot of times in this kind of environment, when we talk about stories it feels like it’s kind of—soft, you know. Like it’s kind of like a soft art. But it’s actually really really important. It’s as important as anything else that we do here.

Slavin: with that, I just want to say that I introduced the wrong Warren Ellis in part because one of my students said, “Are you really gonna have that guy from Nick Cave on stage?” And I was like, “I uh…no.”

Ellis: It happens. Other members of these bands have emailed me thinking I’m the other guy. I got this long email once from Blixa Bargeld… I hadn’t seen him in six months. Here’s a list of all our mutual friends who’ve died or gone insane in the last 6 months. And I had to write back and say, “I’m not that guy.” And he said, “Oh. Would you like to know more about my friends who have died and gone insane?” And we were emailing for about a week. Then he had a gig on a Saturday and dedicated a song to me, so.

But when the other Warren Ellis grew a beard…

Slavin: I know, it’s confusing.

Ellis: When the other Warren Ellis grew a beard, a girl at his record company emailed me and said, “Our Warren Ellis has just grown a horrible beard. I blame you. He was beautiful and now he’s ruined.”

Slavin: Well, to the other Warren Ellis.

Ellis: Well, no. Fuck the other Warren Ellis. He tried to have me killed. There’s b-roll of Nick Cave and the other Warren Ellis during an interview in Paris. And they just kept it rolling. And the other Warren Ellis starts complaining about other people bringing him my books to sign. Which, he obviously found quite annoying. And Nick Cave turned round to him and said, “Well, we could just have a hit put out on him. We could just have him killed, would that sort it?”

Slavin: On film.

Ellis: And then that got put on YouTube, so yeah. Thanks for that, guys.

Slavin: Well, it’s worth noting that where I’m from, you’re the primary Warren Ellis.

Ellis: [laughs]

Slavin: I’m sure you know— I mean, this is in Brighton. And it’s funny because I had forgotten about this, but I was doing a Google Images search in my own photos and I found this. And this is amazing. This is just some cafe in Brighton that this is what you have to sit through if you want to eat there.

Ellis: I was in Brighton last September. I haven’t seen that before.

Slavin: You don’t know about this.

Ellis: No.

Slavin: I mean, I’m sure there’s lots of things you don’t know about, but it’s a really—

Ellis: No, I haven’t seen that at all.

Slavin: It’s a really good one. So okay. I’ll tell you the story of how… So I knew I knew about you for a long time, but the the story how I first got really really interested in you is—forgive me for putting these faces in front of you—

Ellis: Oh, the BERG boys.

Slavin: The BERG boys. So, these people are connected here in that Matt Jones there worked for Marko Ahtisaari at Nokia probably about a year before this was taken. And Jack Schulze sat right here and gave a talk about two years ago. And there’s also a Timo Arnall, who’s not in this picture but so I put in there, just to say that he’s an important part of this. And there were a couple things that we had in common. They liked beer, they liked Fuck Buttons, and they liked comic books.

And so they were the ones that really kind of brought— Like, I didn’t really know about Planetary before Jones put me onto it. And so it was really sort of becoming aware of—for me personally, becoming aware you work through their filter. And now I should say that these guys are bunch of designers. This is a firm that’s now defunct, which I guess you named, technically.

Ellis: I actually named them, yeah. They were Schulze and Webb [crosstalk]

Slavin: Yeah. Not a good name.

Ellis: And then Jones joined. And they needed a new company name. So, they were called BERG, but that was an acronym for the British Experimental Rocket Group.

Slavin: Which…they are not the British Experiment Rocket Group. But they are BERG.

Ellis: And then had lab coats made.

Slavin: They did have lab coats made, it’s true.

Ellis: And they made one for me, and they made one for William Gibson.

Slavin: Aw. It’s good. It’s good. So I’m bringing them up in relationship to you because I think that there’s this thing that I want to kind of tease out, and maybe this is totally specious—

Ellis: Yeah, I mean it’s worth mentioning at first I actually met you through them.

Slavin: Yeah, yeah.

Ellis: Yeah, I was at that shitty pub on Elm Street with no signal that they liked.

Slavin: No, it was at Geoff Manaugh’s thing at the AA.

Ellis: Was it?

Slavin: Yeah. Anyway, that was a long time ago. Anyway. But I think that there’s something with the work that these guys were doing— And I should say that they all went through, or most of them went through the Royal College of Art.

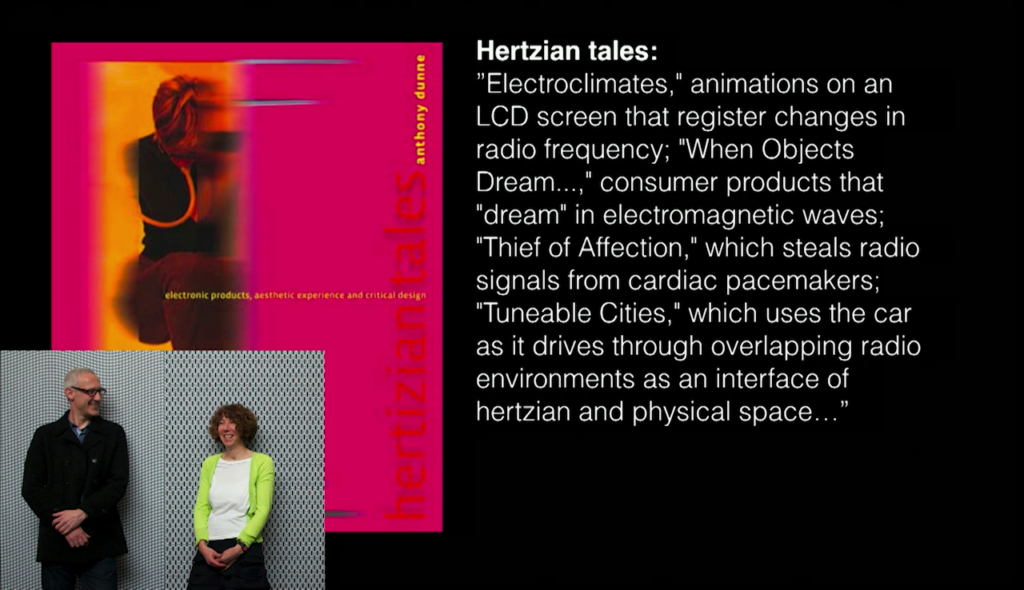

And you probably know these guys by now, Tony Dunne and Fiona Raby. They’ve spoken here. They were part of Knotty Objects. I think that they might have been [?] tutors at the RCA. And Tony wrote this book called Hertzian Tales, which is very good, that includes these sort of ideas of like, electroclimates, animations on an LCD screen that register changes in radio frequency; consumer products that dream in electromagnetic waves; Steve of Affection, which steals radio signals from cardiac pacemakers; and that this was sort of like, that these guys were sort irradiated, you know, by that world. And then they were really really interested in this this kind of work, which— [following video is played from ~1:13–1:45 as they speak]

Ellis: Oh, this’ll be the RFID tag.

Slavin: Right, sort of trying to find— This is Timo Arnall and Jack Schulze—

Ellis: In a basement in in Oslo.

Slavin: In a basement in Oslo. That’s the only place it’s safe to do this, really. And they’re basically trying to find the boundaries of the RFID transmissions, to start thinking about these things as material, and to make these things visible. [following video is played from ~4:02–4:45 as they speak]

And the same thing with WiFi—very clever idea—to show WiFi signal strength and then you do time lapse exposure, etc. But the thing is that they were interested in those things, but they were also really interested in you. And I think, I guess what I want to suggest is that maybe that’s part of what they were interested in, and that it’s made concrete in that you guys did a collaboration together, right?

Ellis: We did in the end, yeah.

Slavin: And this was the writing credit for it, right? Is that right? Do I have that right?

Ellis: Yes. Yes, Jack being Jack.

Slavin: And it was a comic book called SVK. So you can talk about this better than—

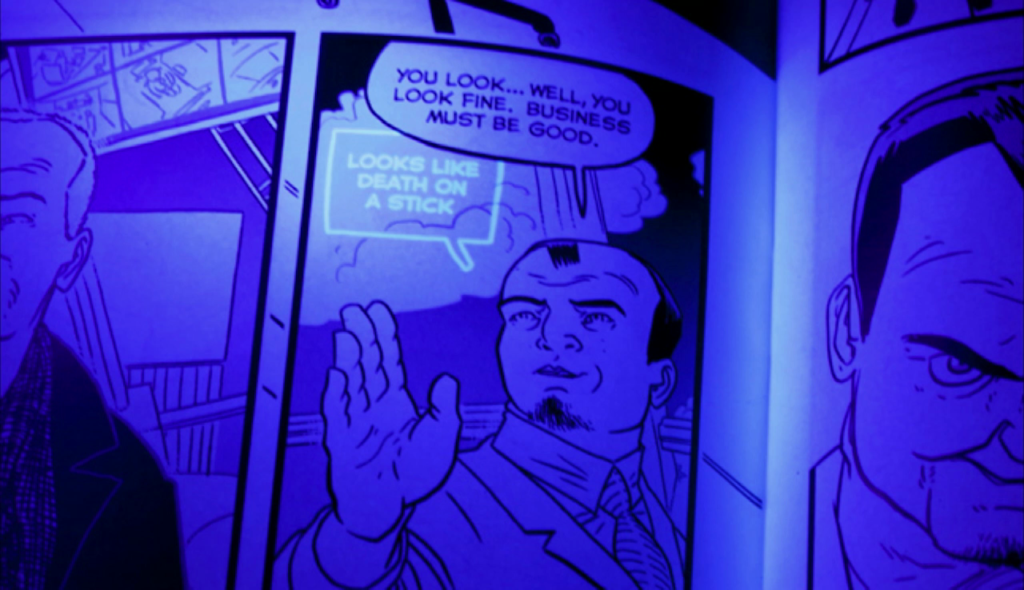

Ellis: Well I mean, they had this idea of a comic book that we printed in black and white in one color, and also UV ink that would be completely invisible until you shone a UV torch on it. So Jack had the idea you could have a story nested within a story. And you would reach a point in the story where you were told to use the UV torch in the same way that in old 3D films you’d be told when to put the 3D glasses on. And then you discover this whole new level to the story that you didn’t know was there before. And then you could read backwards with the torch and find out aspects of the plot that were hidden from the protagonist because they were happening in this invisible space.

Slavin: And I mean, it’s very BERG, it’s very Jack, but I think it’s also kind of, it’s very you.

Ellis: It’s kind of paranoid…

Slavin: Meaning, like—

Ellis: Paranoid and shitty. Just always assuming that someone is hiding something from you. I mean, I don’t want to go the whole Burroughs route of being paranoid.

Slavin: You don’t want to go full Burroughs.

Ellis: Yeah yeah. You don’t want to go full Burroughs. But that said, all our public and private spaces are largely defined by what’s being hidden from us. And what’s being done with the data we generate that we don’t know about, and what we’re not being told.

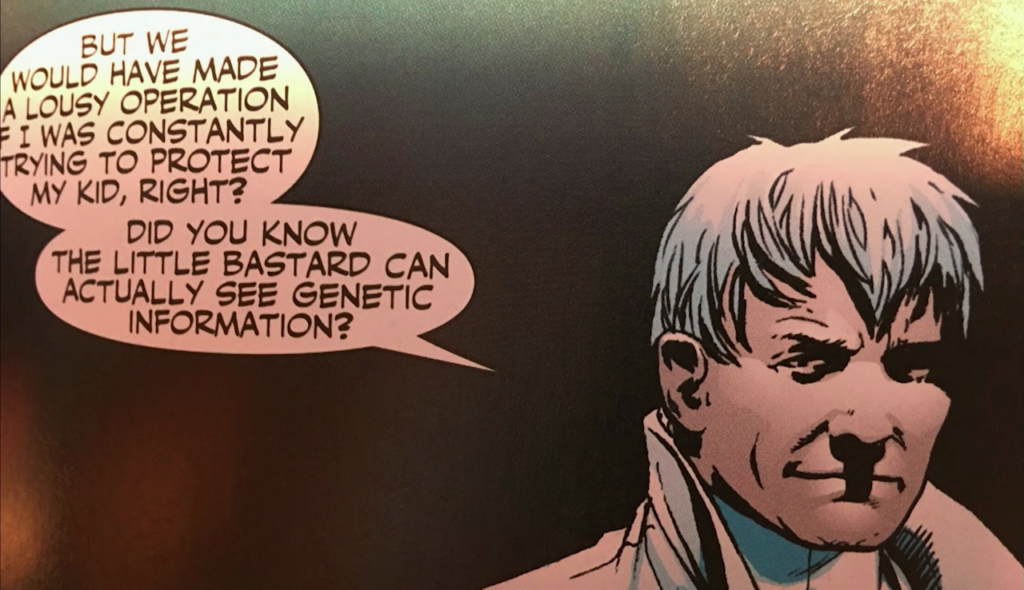

Slavin: So, I feel like there’s a lot of characters in a lot of your work that basically are like, they are the person that can see the things that nobody else can see, in one way or another. [crosstalk] It’s like that they’re these perceptive—

Ellis: On one lever or another. I mean that was the point of SVK, in fact.

Slavin: Right, and here it’s blatant, right.

Ellis: Yeah. In other stories…

Slavin: Here, like there’s The Drummer…

Ellis: Right, magic is code and code is magic.

Slavin: Right. The whole point of magic being you are entering into conversation with something that is not necessarily there, or at least not necessarily visible unless you do the things required to have that conversation. Crowley called it conversation with the angels. But what he actually—that’s just dressing up our being able to access parts of your own subconscious that are usually available. That was the point of those rituals.

Slavin: There are a lot of things, particularly in big, mythic storytelling. There are a lot of aspects of that that are about being in conversation with something you otherwise cannot ordinarily see.

Slavin: Yeah.

Ellis: But yet exerts a pressure on the world.

Slavin: Exerts a pressure on the world…like, it can in some way have you know—

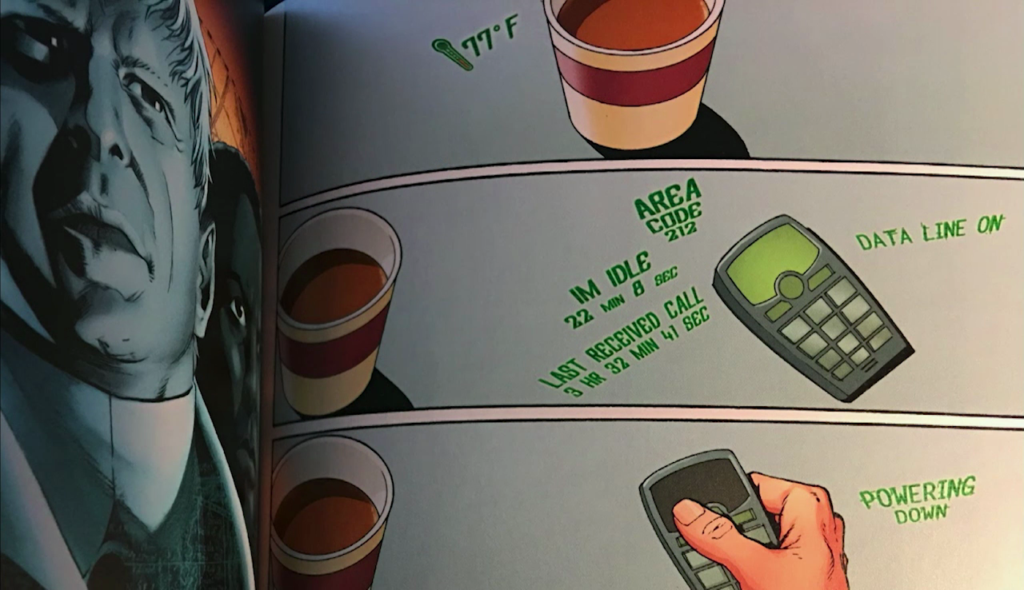

Ellis: No I mean, this one here. There was a whole sequence there about just being able to see actual like, temperature readouts.

Slavin: Right. And I think there’s one where…

Ellis: Yeah.

Slavin: Yeah, right. Like that idea that The Drummer can actually understand—

Ellis: He can actually spot base pairs from sixty feet, yeah.

Slavin: It’s so good. And I think that I’ve seeing that I guess in different ways, and sometimes you explicitly link it to magic and consciousness—

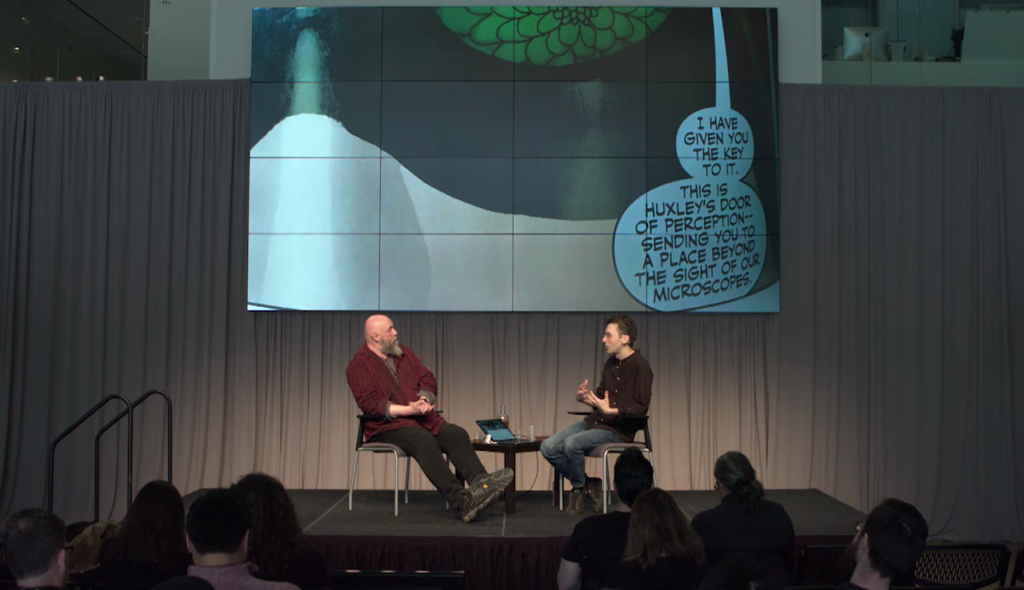

Ellis: Well, I mention Huxley there. That was the whole last half of Huxley’s life. He did psilocybin, and ten minutes later he was looking at his own trousers and saying to himself, “Yes, this is how one ought to see.” There was a whole new level of detail and art to the world that almost appeared to him like it must always have been present but he simply wasn’t able to see it until he took the drug.

Slavin: So does that superpowers?

Ellis: Yeah, I think that’s a big part of the appeal for a lot of people. I think if you ask anyone who’s smoked DMT, for example. It’s the whole just going into hyperspace aspect of it, and moving at light speed. You know, any good drug does convey that sense of being able to do or perceive something that you couldn’t do before.

Slavin: Yeah. I think also…I mean, you you seem also interested in… Like, putting drugs aside for a second. You seem interested in aspects of science and technology that also allow these additionally sort of enlightened ways of seeing.

Ellis: Yeah. I mean, this is why I get lumped in with the transhumanists a lot of the time. Which I tend to reject because all you’re talking about is tool-using. I just want bigger and better and fancier and cleverer tools. The whole transhuman thing interests me much less than continuing unabated the stream of technological process that includes your glasses. Improving our ability to perceive our environment.

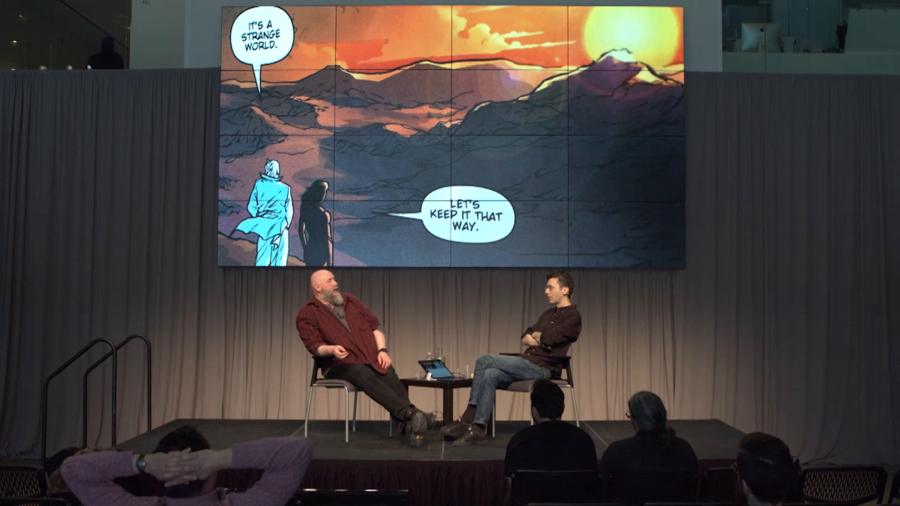

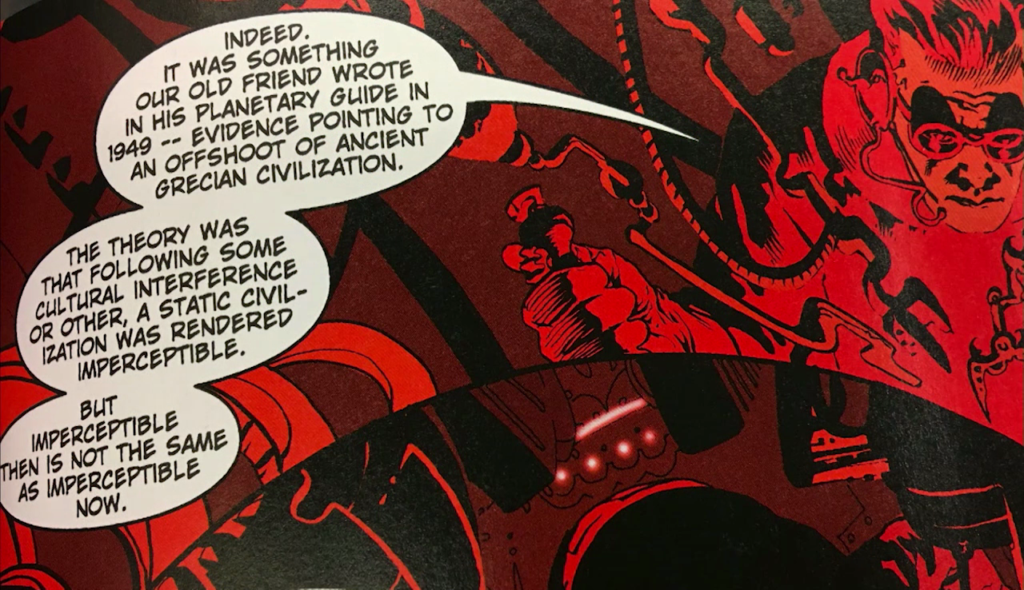

Slavin: Yeah. Yeah. It’s woven so thoroughly— This is such a beautiful thing from Planetary. And this is a very different point. But one of the interesting things about Planetary is that it’s sort not speculative fiction about the future, it’s sort of speculative about the past.

Ellis: Yeah.

Slavin: Right, I mean that’s one of its magic elements.

Ellis: Yeah.

Slavin: But it’s such a beautiful thing, right. And this is in reference I guess to Wonder Woman’s island, something. But it’s that thing, imperceptible then is not the same as imperceptible now. And it’s such a nice idea that just putting aside superpowers, just human perception shifts as we evolve. We evolve with these tools. And it’s a beautiful thing.

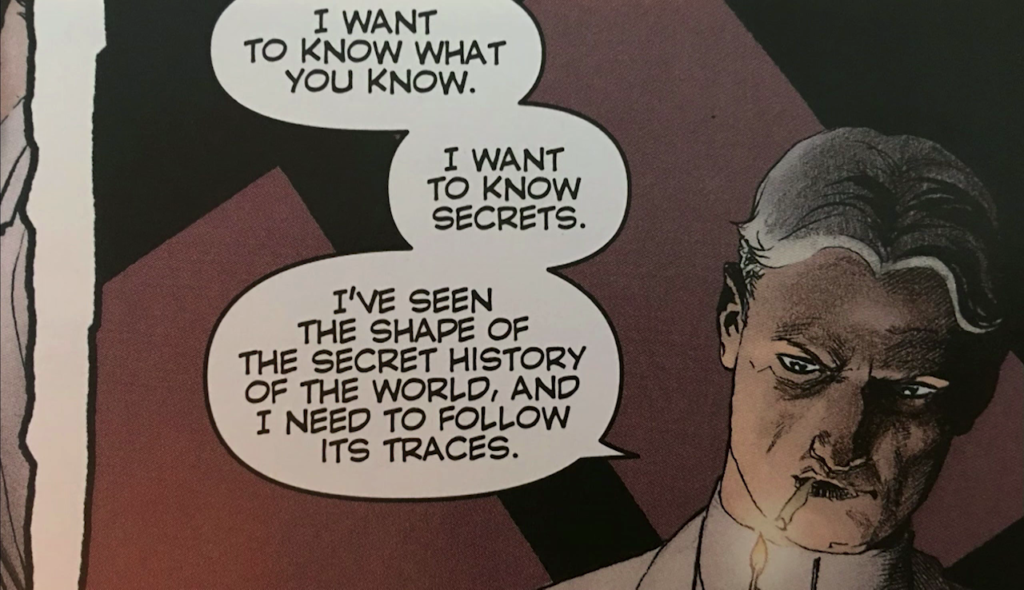

Slavin: just here where you link information directly to magic. There are all these interesting things… Like I say, for me although I’d known some of your work before, Planetary was the first time where it was just like oh God, it’s like “the box is much bigger on the inside”-type experience. And one of the interesting things about the characters in Planetary is their job, right. They’re anthropologists.

Ellis: They’re archaeologists.

Slavin: They’re archaeologists, sorry. Which is not the conventional superhero role, right.

Ellis: No. Planetary is one of those odd books where it’s about superhero fiction, and particularly the roots of superhero fiction, without necessarily some of the time being a superhero book.

Slavin: Right.

Ellis: So yeah, they’re archaeologists. But that in itself plays into some of things we understand about adventure fiction. Because of course Indiana Jones was an archaeologist.

Slavin: Right, that’s true.

Ellis: And yet we don’t think of those as films about archaeology.

Slavin: Right. Conventionally. Yes.

Ellis: Conventionally. I mean, I would’ve been up for that, certainly. Because you know, I’ve got these two great loves, history and the future. I love futurism, I love history and archaeology.

Slavin: Yeah. And I think— I mean, part of what you do explicitly in Planetary, and I think in other things too, is looking at the futures that we could’ve had, should’ve had, might’ve had, might be having, [crosstalk] all at the same time.

Ellis: Yes, yes. The roster of disappointing non-futures. Jetpacks and flying cars and wrist radios.

Slavin: Yeah. Which is…it’s the explicit subject of your new book, right, of Normal, which is the idea that this is about people who are scenario planners. You divide it up into two different types—

Ellis: Yeah, I divide them up into into foresight strategy, which are people who work at institutions and nonprofits; and strategic forecasting, which are people who work for private security corporations and spook houses. But they’re all futurists. They’re all engaged in the process of trying to figure out what’s coming next. And I’ve done a lot of these futurism conferences and festivals over the years, and eventually I saw a pattern. Which was these people get really, really fucking depressed.

Slavin: Yeah. You call it the abyss gaze.

Ellis: Abyss gaze, yeah. If you’re working, for example, in forecasting climate change or climate mitigation strategies, you’re gazing into the abyss all day and the abyss gazes back into you and tells you we’re all doomed. So you can do that for a while, and then eventually someone has to give you a shitload of Valium and put you to bed for six months because it’s a really really depressing gig. You’re thinking about the end of the world all day.

Slavin: Right. And so this is about the sort of recovery facility.

Ellis: This is where they end up, Normal Head.

Slavin: Normal Head, Oregon, right.

Ellis: Yeah, Normal Head, Oregon. Which is a hospital in the middle of an experimental forest, for broken futurists. It’s a rest home for mad people who think about the future. And everyone asks me the same question. And I don’t know if you’re going to do it, but I’m going to preempt. No, I didn’t write it so I could go there.

Slavin: I…I wasn’t going to ask that. I was going to ask you if you’d been there.

Ellis: [laughs]

Slavin: But that’s different.

Ellis: I’ve been in the area.

Slavin: That’s a different question.

Ellis: I used Oregon because I’ve spent some time there. And just the landscape is fantastic for that.

Slavin: But there’s…I think through a lot of your work, the people who can see the things that nobody else wants to see or can’t see, whatever, they’re not as happy as everybody else, right? In general, although not all the way. But in general, it’s not revealing wonder, necessarily, right?

Ellis: I mean, for the purposes of the books, no. Because if these people were happy in their work it would be more difficult to write drama about it.

Slavin: Yeah, funny that. Right.

Ellis: If nothing else, I’m probably not going to sell a book called you know, “The Glitter and Unicorns of the Future.” I’m probably not going to—someone else might. No one’s actually going to believe I wrote that, for one thing. I’d have to use a pseudonym.

But at this juncture, a lot of the time, when you’re working in very specialized areas like for instance climate change mitigation, you’re not looking at a happy ending. The best you’re looking at is holding fast, holding a plateau is probably victory condition. It’s a depressing gig.

Slavin: It is a depressing gig. But I think there are also the moments in a lot of your work where it does reveal a kind of wonder and weird magic underneath it.

Ellis: Oh yeah. I mean, the future is on the whole a wonderful thing because it will bring us new things that we haven’t seen before. And that’s why we stick around.

Slavin: It’s one good reason, yeah.

Ellis: Yeah.

Slavin: Yeah.

Ellis: That and the fact I don’t want to die.

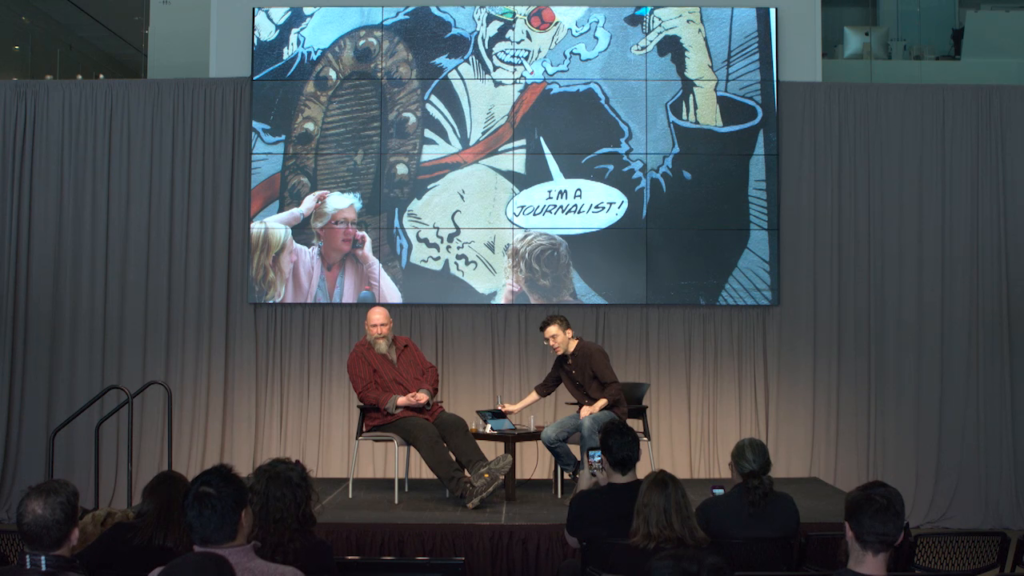

Slavin: There’s also the idea that… So, some of these characters are archaeologists. But it would be remiss to not include the journalist, so—

Ellis: Ah, that old bastard.

Slavin: Yeah. So, for people here who actually came to see the other Warren Ellis [Ellis laughs], can you explain who this is?

Ellis: That is Spider Jerusalem, a journalist in an undefined future point. It’s basically Hunter S. Thompson in the 21st century, was my initial idea. He didn’t turn out quite like that, but yeah, he’s a version of gonzo journalist in the future that I started writing…about twenty years ago. A little over now, actually.

Slavin: I mean, a lot of what you have in there, it’s twenty years ago and a lot of it is sort of stunningly prescient.

Ellis: Some of it’s disturbing in that way, yeah, because science fiction isn’t or shouldn’t be a literature of prediction. It should be a literature of speculation that acts as an early warning weather system. And writers should never set themselves up as making predictions, because not only is it a really really fast way to make yourself look really bloody stupid— I mean, you might as well be predicting the end of the world in 2012, you know. But also it misses the point of what we do. It misses the point that we use aspects of the future and speculation as tools with which to examine the present-day condition.

Which is why this book in particular, there were two politicians in there. one characterized as The Beast and one characterized as The Smiler. And every two years I’ll get a slew of email or tweets or something telling me that wherever in the world they are, on that election cycle, they think they’ve got a politician who’s The Smiler and one who’s The Beast.

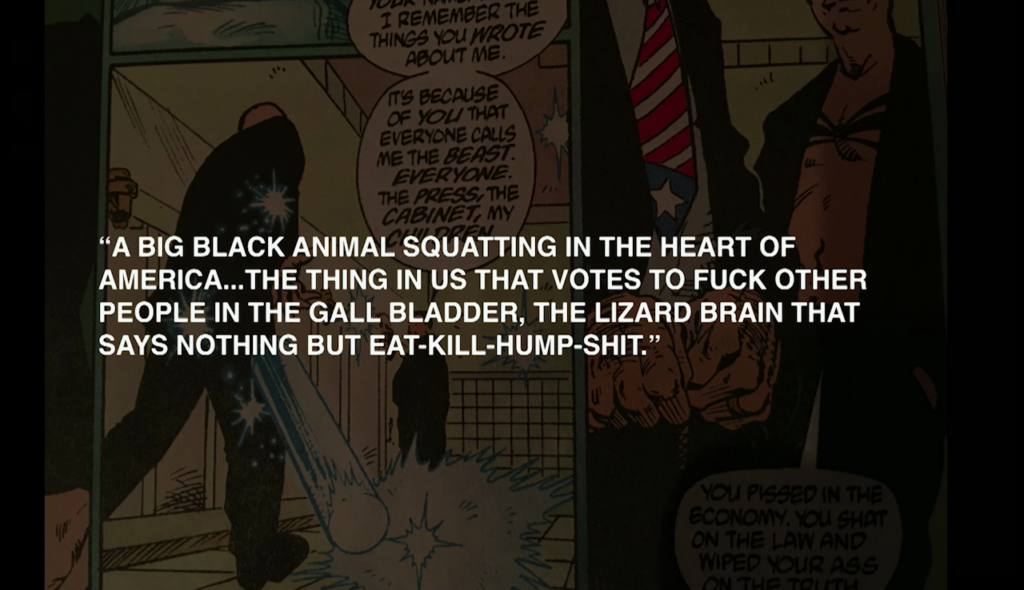

Slavin: This this is the quote from your character Spider Jerusalem about The Beast that is just so amazing, “A big black animal squatting in the heart of America… The thing in us that votes to fuck other people in the gall bladder, the lizard brain that says nothing but eat-kill-hump-shit.”

Ellis: I used to drink quite a lot.

Slavin: And that’s… In the scale of things, right, that’s kind of, not the good guy but it’s not the worst thing that could’ve happened.

Ellis: Unfortunately it’s not the worst thing that could’ve happened.

Slavin: Right, yeah.

Ellis: Did I tell you that I absolutely terrified Stoya the other month in New York. Actually she turned white. Because there’s The Beast and The Smiler, and there’s another character in here called Heller, who’s an independent politician who essentially throws rallies. And it’s all very reality television and glitzy and all. And she said you know, “Who’s Trump?” Is he The Smiler or The Beast. And I said what if he’s Heller. Heller actually quotes from Mein Kampf at one point in the book. And she just went dead white and, “Holy shit, no.”

Slavin: I mean, you you kinda nailed it in general, right, where we’re at, politically. No?

Ellis: I would hesitate to agree, um…just because I don’t want to be right.

Slavin: Okay.

Ellis: Because you know, I was writing something really kind of fucked up and I’m not sure I want to cop to, “Yes! It’s all my fault. I wrote 2017. Just leave your tip by the door.”

Slavin: But I think it’s also interesting that the central character in this dark political future/present is a journalist, in that they’re declared now by White House spokespeople as the enemy—

Ellis: As the enemy of the people, yeah.

Slavin: —explicitly.

Ellis: Having him as a journalist was actually a science fictional choice. I’d been approached to write a piece of science fiction about the future. And nobody bought science fiction in comics in those days. It didn’t sell. Science fiction in comics—in Anglophone comics—was assumed to not work, unless it was Judge Dredd in Britain. So I wanted to find a way to once again make visual science fiction in print work for an American audience.

Slavin: I went back to the start of American science fiction, Hugo Gernsback, whose first big science fiction story, which is one of the defining pieces of the genre and it really kickstarted science fiction in America, was called Ralph 124C 41+. And that character, I think he was like a pop star surgeon or something—and this story was written in like 1925. But the whole point was he led us through the world. He was Ralph 124C 41. He was that character who was able through dint of his profession and his place in society to explain this future society to the readership as he went through the story. He was the griot. Who are our griots? Who are the people we have to explain society to us? To say, “Here’s where I think I am today. This is what I think it looks like.” That’s a journalist’s job.

Slavin: Right. Yeah. But twenty years ago… I mean okay, yeah. It has the gonzo quality of Hunter S. Thompson and—but it’s much… Putting aside the traditional idea of gonzo, it’s very close to how journalists have to operate today.

Ellis: Unfortunately that’s one of the things that happened that people have cite me for from time to time. That it now happens on the street now with the digital connection.

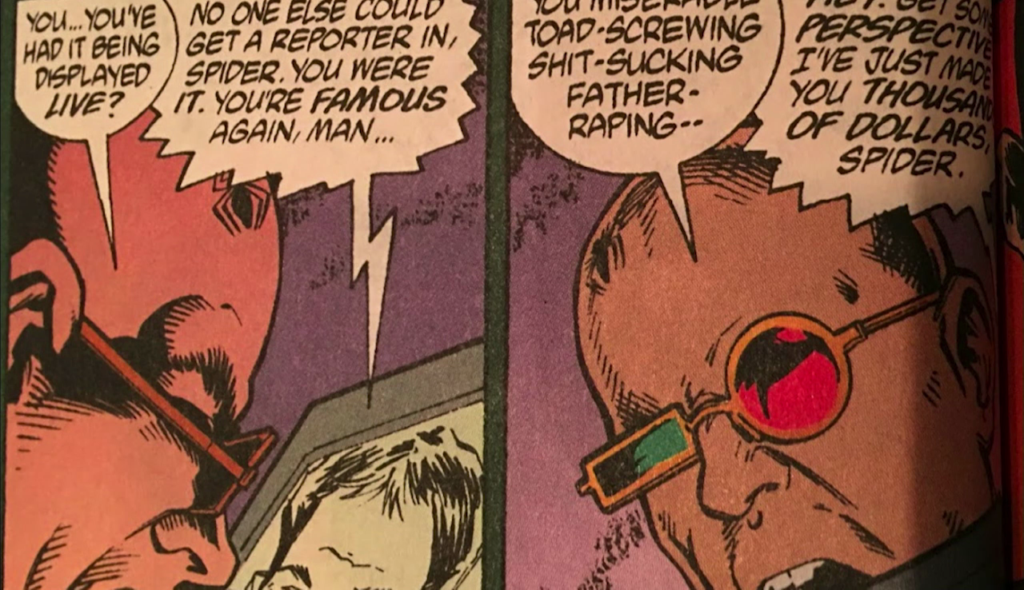

Slavin: There’s a scene where he’s filing a story on his typewriter—

Ellis: Laptop, yes. Typewriter laptop. I stole that from the Max Headroom TV series. They have these big desktop computers in the Max Headroom TV show, but they all had Underwood keyboard chassis.

Slavin: Nice. But in this story, he’s filing a story online and the editor basically flipped a switch and has it—

Ellis: And streams it.

Slavin: Streams it, yeah. And it’s like man, that’s tweetstorm, right? Or that’s live blogging. Or whatever it is that we’re calling it now, the idea that journalism is kind of a performative act I think is really… Just like, you saw it, I saw it here first.

Ellis: Right.

Slavin: Or maybe George Plimpton first. But still. And also we should talk about his glasses, right. Which is also…I it’s not bad, right. I mean, what is it, the right lens is recording?

Ellis: I don’t remember which lens is taking the photos, but you know, I thought was so clever. I think there’s a comment in one issue about how it’s got 20 gig of onboard memory. Which in 1997 just sounded monstrous. That’s a computer the size of a room in NASA. Twenty whole gigabytes.

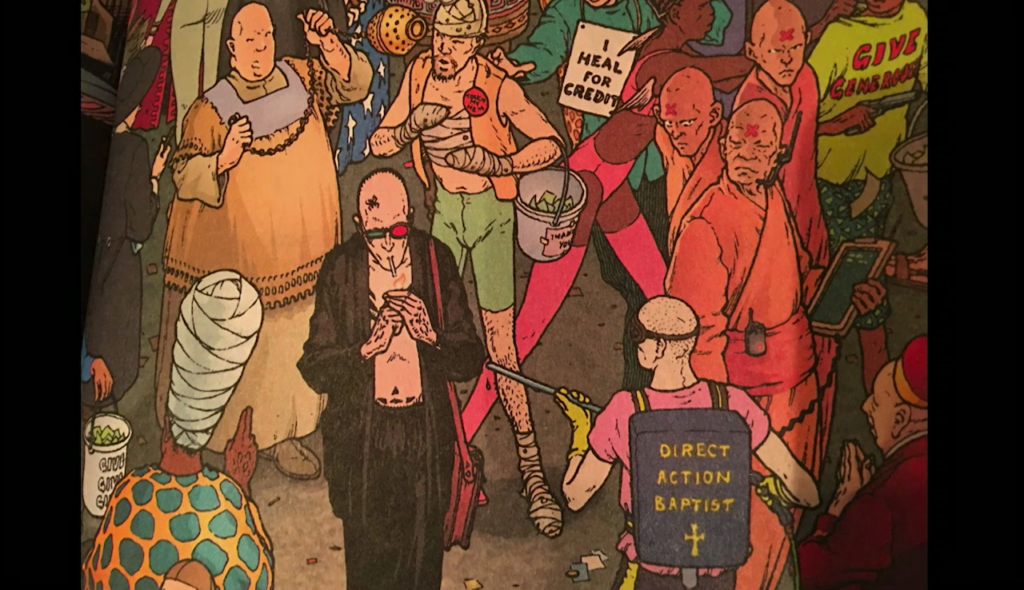

Slavin: Of all the things in Transmetropolitan’s future, the thing that was most familiar to me when I first saw it was that vision of the city, which reminded me— I grew up getting kind of like, they would just fall off trucks, like loose copies of 2000 AD. And they were weird, because they were sort of about…they were British comics about American culture—

Ellis: Yes.

Slavin: And sort of like a hyperbolic American culture. But part of what was most interesting was the vision of these cities as somewhere in between like you know, Brueghel and Bosch, right. Like where the sensibility of everyday life is just everywhere. I think I grabbed one of them. Like you know, this city:

This was kind of like the city that I grew up looking at in 2000 AD, Heavy Metal… And the idea of using comics to describe that world with such detail and precision and the kind of heterogeneity of it was just like…

Ellis: Well I mean, I was lucky and I had great artists.

Slavin: Yeah, also.

Ellis: I had Darick Robertson drawing the book, who was amazing. And he really grasped that I was after that fusion of the European comic style with a more textural and slightly more open American feel to it. Because what we get wrong in Britain—or what we used to get, of course—was due to the fact that we were only exposed to landscapes of America through television. We got the sense of American cities being hypercompressed places like ours, because we have no sprawl because we don’t have the space. You’ll fall of the end of the country into the bloody sea.

Slavin: we imagine… When we se as a shot of Manhattan, we assume it’s the size of London and everything’s just rammed in there and straight up. So you get these American fantasies from European writers and artists of these places being hypercompressed melting pots.

Slavin: It’s like Karl May writing westerns, never having left Germany.

Ellis: Right. But with an American artist like Darick Robertson in there, he actually grounded it a lot more and made it feel more like an American space. But still with the mania that the Europeans get when they look at America.

Slavin: So, there’s Alex McDowell—have ever crossed paths with him? He’s a production designer. Works a lot with Spielberg, and has a lot of connections to the Lab. Has often…well I don’t know if often, but he has occasionally come to the Lab and sort of tried to get a sense of what the Media Lab thinks the future looks like, and it makes its way into things like Minority Report or other things. But he’s a production designer—he’s probably one of the best production designers in Hollywood. And he has a whole thing about like, that you can start a film by thinking about the city that it takes place in, rather than the characters or the narrative per se. And that if you can do that with with absolute precision, then characters and narrative start to unfold.

Ellis: Yeah, I mean you can start a story anywhere. But I’ve quite frequently started building a story with the location. Because the kinds of story and the kind of people that will eventually populate the story are suggested by the location.

Slavin: Right. That’s interesting. Because a lot of… I mean, the comics that I’ve been most interested in, they hop all over the world. And then they’ll land here, and it will be very very precise. And so you’re thinking about those cities as kind of—

Ellis: Well yeah. I mean every job’s different, every story starts a different way. But something like Ignition City, which was an alternate history set around 1950 in a place called Ignition City, which was Earth’s last spaceport on a circular artificial island. And the launchpads were all around the edge, and there was a settlement in the middle. And I came up with that first and what the weather would be like there. And then you start thinking well, who ends up in the middle? Why would you live in the middle of a ring of launchpads? And the characters and the conflicts and the storyforms get generated out of that. You can start a story anywhere; starting with the city is as good a place as any. I’ll take it any way it comes.

Slavin: So, a lot of your work is working with existing IP. Like Iron Man, or—

Ellis: Has been, yeah.

Slavin: Has been, okay. How do you… I mean, a lot of people give you the appropriate credit for really rethinking what Iron Man is and does and means. How do you turn a corner of something that has so much weight underneath it?

Ellis: You mustn’t think of comics like an industry that functions the way you would think a business filled with adults would.

Slavin: It is how you imagined it.

Ellis: It is the most wildly…random…unfocused, ass backwards business on Earth.

Slavin: There’s a lot of competition amongst it.

Ellis: Oh yeah. Oh yeah. So here’s what happened with Iron Man. Joe Quesada emailed me one night and said, “We don’t know what to do with Iron Man. What would you do, if you were doing Iron Man, because we’re stuck?” And I had a coffee and I thought about it for about ten minutes and I sent him an email, saying, “The whole point of Tony Stark is that he’s the test pilot for the future.”

Slavin: It’s so good.

Ellis: And he emailed back and said, “You start Monday. I need six issues.” That was literally it. There was no plan. It was like, “Okay. Yeah. That’s great. We like that. You’re writing Iron Man for six issues now. The help is out here. Thanks very much. Done.” That was the extent of it. So it all came from that. Comics is a really loose business in a lot of ways. And once you’ve done a certain amount of work and people know how you think and when to expect the scripts, and how late you’re going to be…it gets very loose. Much of the work I’ve done at Marvel Comics in the last fifteen years I haven’t actually written pitches for. it’s just been a series of emails and then there’s, “Great. Off you go.”

Slavin: Is there a lot of revision and going back to—

Ellis: Not a lot. They don’t ever trust me with anything important, is the thing. Anything that’s actually valuable to them that I might break they won’t let me near. They kind of keep me in the basement. It’s a basement laboratory, where I’m allowed to experiment on anything that might get pushed through the door, but I’m not allowed to go roaming for fresh meat in case I touch anything important that’s valuable to them. So they largely leave me alone to see what I’m going to grow in the lab. And I’ve got a similar situation at DC right now, where I wrote a slightly more expansive outline, but it was really “let’s just see Warren builds in there.” It’s a Tom Waits song. What is he building in there?

Slavin: There’s this idea that…

Ellis: Oh bloody hell. I should’ve known James Bridle would be in the room at some point.

Slavin: Yeah, I don’t do any of these without invoking James Bridle at least once.

Ellis: I did a thing in New York a couple of years ago and I talked about James and joked that he was probably hiding under a table somewhere in the room. And then afterwards he appeared.

Slavin: Yeah, he’ll do that.

Ellis: Yeah.

Slavin: Yeah. [crosstalk] And then disappear with a puff of smoke.

Ellis: A fucking apparition, it’s terrifying.

Slavin: This is James Bridle—

Ellis: Hi, James!

Slavin: And he gave a talk probably like five, six years ago that really stays with me about how writers work. And he talks about— So, he notes this interview with William Gibson, an interview evidently conducted by a bot. And he says, “No, I’ve got Word open on top of Firefox.” And the idea that he’s writing in a hyperlinked way. It’s not about closing himself off to everything in the world, it’s as actually about keeping a strong line open and that you can start to see that in his fiction. You can see those lines going out to Google or whatever it is. And I don’t know, is it different to write on top of Twitter? I mean, do you you write on top of something?

Ellis: I mean, you could tell when it shifted for Bill, because you could spot when he’d gone down a wikihole.

Slavin: Uh huh, yeah. Yes.

Ellis: It’s like…Israelite tactical sneakers? Hmmm. How many hours of your life did you lose on that one?

Slavin: Right. And as James points out, then you Google and you realize like wow, I’m looking at the exact same fucking thing that he was looking at.

Ellis: Exactly, exactly. Because there’s only one page like that that on the Web, so you know you found the same one he found. I’ve got Word open on top of Chrome. Because I like living in 2017 and I like not having to go down to the bloody library and order books. Or not being allowed to take a book out of the building and having to read it there in the room to get it what I need. My stuff has always been research-intensive.

Slavin: Yeah I mean, the science in your science fiction is no bullshit.

Ellis: It’s a little bullshit, it’s a little skewed…

Slavin: It’s stretched. I mean, it’s science fiction.

Ellis: Yeah. I mean, I have no educational background whatsoever. I’m basically as stupid as mud. So, I understand science in terms of the story it presents, in terms of the picture it paints. Science stories appear to me as instances of art and that’s how I understand them. So my use of science is probably usually three degrees south of correct.

Slavin: Sure. But I think—

Ellis: But it [crosstalk] hangs together.

Slavin: You go deeper than any other comic writer, for sure, right?

Ellis: I’ll take your word for it. I don’t get to read [inaudible] anymore.

Slavin: But I just mean that you do seem to put a lot of work into getting it right.

Ellis: Yeah, as right as I can.

Slavin: And I think in the same way that you can tell— There’s a certain sense with William Gibson, or anybody else, where you can see like oh, this is he went down a wikihole, there are these moments where it’s like wow, Warren really went off for a while on this one and came back with this thing. And you know, it’s interesting. It’s just like reading comics that you did twenty years ago, where it’s like you know, that science was actually pretty state of the art in that moment.

Ellis: Yeah.

Slavin: And you you seem to be very good at being right on the edge of whatever is happening.

Ellis: I’ve always tried to be, because that’s just where the really interesting stuff is, it’s where the stories are. It’s where what’s gonna to happen next emanates from. And I wanna see what’s next.

Kevin Slavin: We should open it up for questions, speaking of what’s next. And I don’t know exactly how to do that… Okay, I do know how to do that.

Warren Ellis: We needed the bouncy microphone from yesterday.

Slavin: Okay, here’s one question that somebody asked on Twitter, which is which potential future scares you the most?

Ellis: The thing about answering that question is you have to understand it doesn’t scare me for myself, because I will be dead long before it happens. I’ve got maybe twenty years. So when we talk about the future, we’re talking about a time where I will already be dead. So it’s you people who’ll have to live through it, which you know, obviously I apologize for but on another level I don’t care because I’ll be dead.

It’s climate change. My daughter’s 21, it’s climate change. It’s the environment turning around and just killing us because it’s broken. That’s what scares me more than anything.

Slavin: Yeah, seems pretty straightforward. I don’t know, anybody have a cheerier question?

Audience 1: Hi. How do you depict sitting in front of a computer all day, visually, without it being super boring? Because that kind of feels like the present and the near future.

Ellis: It’s a really tough one. It’s a really tough one. I mean this is something I had to solve in Transmetropolitan, or try to. Because before I got going I’d read an interview with David Cronenberg, who’d just made The Naked Lunch as a film with Peter Weller. And Cronenberg had to try and solve the same thing, how do you make writing look interesting? Do you give the guy a hat? Well shit, no one’s going to stay in the auditorium because you gave him a fucking hat, what do you do? So you start to try and apply a mythic sense to it. It’s exaggeration. And it’s terribly self-serving if you are a writer, writing a writer somehow acting or being depicted mythically. You just got you know…two-feet long ego boner with a cheeseburger on the end, “Yes! I am mighty!”

But trying to externalize the act of writing when you’re writing well is actually less interesting on the page than creating a sense of what that writing is doing to the world. Because great writing changes you, changes other people, and changes the world. So if you can depict that in a way that feels mythic in some sense, you have the sense of the world whirling around to that writer, and those words moving out through the screen to impact the world, or even the world coming back through the screen so the writer can see what he or she hath wrought, is always more interesting than trying to externalize whatever that writer is feeling.

I mean, Cronenberg had some really interesting solutions. I mean the insect typewriter where he had to rub bug powder in the anus. I guarantee you there’s not a writer on Earth who didn’t see that and went, “Yep, sometimes that’s what it’s like. You’ve just gotta rub drugs in your typewriter’s anus.”

I hope that line was too long for Twitter, otherwise I’m going to see that, “Sometimes you just have to rub drugs in your typewriter’s anus,” is just going to scroll up here.

Slavin: Uh, any other questions? I have other things I would bring up. So I really want to talk about Global Frequency. So, Global Frequency I think of all your work for me personally is the one where I read it and I was I was like, that changed how I thought about what the notion of superheroism is. So you tell me if I’ve got this wrong, but it’s basically a thousand people around the world. They may or may not have “superpowers.” They may just be really good at something, like parkour.

Ellis: None of them actually have superpowers.

Slavin: Okay yeah. But they’re a very good parkour runner, or very good at bomb defusing, whatever. They’re all very good at their thing. They’re superpower is in having an operator, Aleph, who can coordinate them, right?

Ellis: Yeah.

Slavin: That to me was like man, I don’t know anything in the genre of comic books that that reminds me— Because that’s not the Justice League, you know. That’s not like a bunch of mutants coming together. Because, you don’t even see the same people from one book to another. So basically there’s only one consistent character—

Ellis: Two.

Slavin: Oh yeah, Aleph and…

Ellis: And Miranda Zero.

Slavin: Yeah. And basically there these thousand people around the world who have a phone that’s on the Global Frequency and can call them at any—

Ellis: There are a thousand and one people on the Global Frequency. It’s a network of experts in any field you may name, who can be brought online at any given moment to effect a rescue of some kind. It’s rescue fiction. I wrote it, actually…the germ of it was after 9/11 I saw someone say, “I wish there’d really been a Superman so he could have saved us that day.” And while I got the sentiment, it felt to me like exactly the wrong thing to say. Hoping for Flying Space Daddy to turn up is gonna get you killed. The only thing that’s going to rescue us is us. And that’s what Global Frequency came out of.

Slavin: And that the power is in coordination and cooperation.

Ellis: Mm.

Slavin: It’s so… I mean it’s really…it’s weird, right, as—

Ellis: It’s weird. Feels a bit dated now, but it’s weird.

Slavin: To me, I mean okay yeah the phone looks a little big.

Ellis: Yeah, a little bit.

Slavin: But actually, that notion of a thousand people being able to coordinate from all over the world at a moment’s notice, I mean that feels totally contemporary. That feels like Anonymous to me, you know. That feels like ISIS to me, right. That feels like this is actually how the world is working, for better and worse.

Ellis: Yeah, this is fifteen years old. This was 2002, 2003, around there.

Slavin: And all the details of it, just the idea that she’s not in an office somewhere. And then you go on to the next one and it’s just like, well who are these two people? Well, they’re also on the Global Frequency and we’re going to go off this way. And it just seems like such a fundamentally powerful…I don’t know, like sort of distillation of the moment that we live in.

Ellis: Maybe? As I say, to me this is fifteen year-old work. And I haven’t thought too hard about it since. It’s been nearly made into a TV show I think four times now.

Slavin: Five’s the charm.

Ellis: They never quite get it there, for some reason. And every time it comes around again, someone will say to me this feels like the conversation of the moment. Obviously you know…not enough to get the thing made. But still, it does seem to be one of those weirdly evergreen ideas, I don’t know how much longer for.

Slavin: I don’t know. I mean, I feel like the world’s going to work more and more like this. I feel like this feels like some authentic vision that—

Ellis: The world is either going to work more and more like that or it’s going to work less and less like that.

Slavin: It’s probably one of the two.

Ellis: In 2017 frankly, I would say less and less. If the world is going to start working in any, way it’s going to be with hyperlocal groups who leave their phones at home before they go to meetings.

Slavin: Yeah. But like… I had something that I was working on and I needed I needed help from…I needed forensic accountants, basically. And so I ended up through a very weird series of whatever, I ended up contacting Anonymous Analytics, which is sort of division of Anonymous that just focuses on forensics, so on and so forth. They were able to turn around…basically I sent them 900 pages. I have no idea who I’m talking to—just Aleph. They turned it around in like an hour.

Ellis: Damn…

Slavin: And I was like shit, that’s some sophisticated coordination on their side. And I’ll never have any idea who I spoke.

Ellis: No, but that’s throwing a lot of bodies at a problem very quickly.

Slavin: Yeah, right. And like, how does it… You know, it’s like people who have jobs. And just the idea that those kinds of machinery exist in the world, and that they’re ethereal and they’re distributed, and there are ways to tap into them through a node is such a… I don’t know, that feels like the poetry of the moment to me.

Ellis: Well, yeah. Maybe someone will make the next generation of that here. Tell that story.

Slavin: We have another question?

Audience 2: Just with Global Frequency, it’s potentially interesting to compare it to Injection as well.

Ellis: Can you raise your voice, young man, I’m old and deaf.

Audience 2: I think it’s interesting to compare Global Frequency to Injection a bit as well, in terms of like, can a group of people, very skilled, coordinating, actually change anything or are they just as doomed as the rest of us, right? And I think what my question is is related to the Global Frequency kind of coordination, but more to the storytelling, where all these stories have these very deep references. We were talking at the wikiholes and things like that. But they’re always talking about the genre, the notion of the story having a specific genre, like you mentioned rescue fiction. Which is a concept I’d never heard before but it made a lot of sense with Global Frequency.

And I think that the notion of having very very strong references just pulling in this grab bag of things but still having a notion of the core genre is an interesting one because I think that my approach to having read a lot of these growing up, my approach to actually working on technology is very much is grabbing random technologies and marinating them and seeing what kind of bubbles out of the muck. And genre is still a real thing, but the notion of discipline has changed, become a little bit more I think like the kind of notion of a genre. Like you’re still pulling in elements from wherever. But you’re telling a mechanical engineering story. And I feel like that’s a kind of Media Lab-y thing that I was also curious to hear your perspective on.

I was wondering if that made sense in terms of understanding the Media Lab as well in terms of thinking of technological disciplines as genres, where you’re pulling in these odds and ends from elsewhere.

Slavin: Oh. Well I mean, I think there’s a stock answer, but it’s a true one, of this idea that what happens at the Media Lab is the things that are between these other things and you’re basically pulling from two things that shouldn’t necessarily connect. I think it’s authentic. I think you see it in the work and in the people. I don’t know another way to work. I mean, I’m no good at discipline.

Ellis: Don’t look at me. My job involves sitting in a room on my own for sixteen hours a day making shit up. I don’t know if it’s a discipline, a curse, or an illness.

Slavin: But you don’t have to choose.

Should I do some of the questions that came in on… From Shay on Twitter, “What role does religion play in the future?”

Ellis: Nothing good.

Slavin: Nothing good.

Ellis: I don’t know if I’ve got a better answer than that, frankly. I would rather religion did not play a part in the future. And it’s like you know, the religions of the world historically, I’ve not enjoyed their work and do not look forward to their next release.

Slavin: You don’t find anything in Scientology kind of cool? A space alien, tied to a volcano, come on.

Ellis: I can appreciate the stories of religions while not appreciating the religions. I mean yes, these are huge mythic constructs. And Scientology is just mad in its iconography and its storytelling. Because it was created by a mad science fiction writer who wanted to get rich quick, went around all his friends and said, “I want to get rich quick. Do you think I should start a religion?” And all his friends laughed and said, “That would be really fucking funny. You should do that.” And he did.

Slavin: Have you ever thought about it, just starting one?

Ellis: Have I ever thought about Scientology?

Slavin: No no no, starting a new one.

Ellis: No, because I used to like meeting those people in the street— Because back in 80s of course they’d say, “Let me tell you about the immortal L. Ron Hubbard.” And of course word of his death did not necessarily get out to all the Scientology churches on time. So I was one of the people who was on the street one day when one of them walked up and said, “Let me tell you about the immortal L. Ron Hubbard.” So I got to say, “I’m really really sorry kid, but he’s dead.” A lot of people got to do that because they actually withheld the insulation—

Slavin: Perfect.

Ellis: —to the churches, so it was in the media before the churches were informed. A lot of Scientologists had very very bad days.

Slavin: One of the conceits in the Transmetropolitan world is that there’s a new religion every six hours, I think, right?

Ellis: Yes.

Slavin: It’s a really nice idea. I think that’s part of what is represented here.

Ellis: Have you ever been to Charlotte, North Carolina?

Slavin: No.

Ellis: Alright.

Slavin: A lot of religions?

Ellis: You pull out of Charlotte— [dogs barking in the background] Jesus, they’ve set the dogs on me. Are you shitting me?

Slavin: Feels like a solvable problem.

Ellis: Alright, there’s actually a horde of dogs be released on the ground floor for me… But you come out of Charlotte airport onto, I swear to God, the Billy Graham Expressway. And there is a line, a row of tiny clapboard churches down the side of the highway, little more than huts. And each one is a different church, a different denomination, of a church. They’ve all got names out of fucking Flannery…Wise Blood. You get to the end and you’re pretty sure it’s the Church of Jesus Without Jesus. They are all technically separate religions, they’re denominations, they’re sects. And there’s a few dozen of them down the side of the highway. So after seeing that, a new religion being generated every six hours doesn’t seem that much of a stretch.

Slavin: Right. Yeah. That’s a plausible outcome. A lot more religions, as as opposed to a lot more religion. Who knows. Anybody else?

Audience 3: I want to follow up on a lot of what’s been said. The basic question is can you talk about some of your inspirations? What I’m really interested in is when you look at something like like Global Frequency, aspects of it are reality today. You can coordinate a global hacking ring with IRC if you wanted to. Some of that is very real. Some things don’t necessarily have any basis of reality. You talk about making things more mythic, which to me means necessarily something that isn’t real. Can you talk about what you look for when you’re looking for “I want that mythic thing. I’m gonna impart this boring activity with something mythic. I’m gonna take this real thing that exists today and make it fit in my universe.” Or for example you’ve been talking about places you’ve been going. You talk about Oregon as an important inspiration. You just told us—

Ellis: Yeah, I’m trying to get at the nut of your question. I’m trying to figure out what the single question was in the middle of that.

Audience 2: Inspiration. So what would you say is your…where do you look for for inspiration?

Ellis: Um…oh God. This is an alternate version of the dreaded “Where do you get your ideas from?”

Audience 2: Yeah.

Ellis: Yeah. In Britain we have people like you taken out and beaten.

Slavin: That’s not fit for the dogs? Fed to wild dogs.

Ellis: They would literally [inaudible] on either side of you, they would lift you up, take you out to the back room and do your kneecaps, son.

Slavin: Is that final answer?

Ellis: It might be. No. Let me at least take a crack at it, bearing in mind this is academe and that I should be more polite than to have you kneecapped.

The honest answer is probably that I simply find it everywhere. Storytelling has to be on some level a response to life, a processing of life, and a re-presentation of life for our consideration. Being able to take a thing in the world, to take an experience, a feeling, an idea, a piece of art, and to make it bigger and turn it around so we can see all its facets and try to understand it from new angles. To me that is just a big part of what storytelling is, and I can’t commit storytelling without being engaged in the world. Even from my distant hermitage on the banks of the River Thames I’m still running three or four screens, I’m still going out every day, I’m still talking to people, I am as engaged in the world as I can be. Without actually seeing another human being from one week to the next, but let’s not talk about that for the moment or I’ll start crying.

But, I’m still engaged in the world and I’m still drawing things out in the world that I want to talk about or that I want to change the angle on so that I can show them to you and say, look at this thing. Did you know it could do this? Have you seen it from this angle? Do you see how great this is? Do you see how terrifying this is? Let me show it to you. Let me make you see for a moment what I see when I look at it. Here’s where I think I am today and this is what I think it looks like. I don’t know if that’s a good answer, but it’s the one I’ve got.

Slavin: I think that’s a…great answer.

Audience 3: You talk about science fiction as sort of speculation and a warning system. I’m curious sort of thinking back to class Star Trek, which is very utopian in vision. Do you think there’s also a role for providing guidance?

Ellis: Star Trek is always a weird example for me. Because it is joyfully utopian. And it’s also completely bloody stupid.

Slavin: It’s bananas.

Ellis: Everybody will have food because spaceships. That’s a weird logic chain. And you know, it didn’t have to be any smarter than that because it was an American TV show in the 1960s. But good, clear-eyed utopian storytelling is always valuable. Honestly, polemical utopian storytelling I’m up for. News From Nowhere is basically a tract. But it’s no less fascinating for that. There is now law that says we must be convincing on a basic mechanical level in our storytelling. Otherwise Star Trek never would’ve gotten made. The point is what it shows up to say, what has it got to say? And whether that is valuable.

Slavin: yeah, if someone shows up with utopian storytelling that has a definite point of view to share and some kind of argument to back it up or at least something to empower—I’m nervous about that word guidance. Even though I’m down for a good tract or polemic like the next person, I’m not completely comfortable, as a writer, with offering guidance. I don’t want to be the wishy-washy liberal artist who says, “I’m here to ask questions not bellow answers.” But, I am nervous in taking an obviously authoritarian role? Or asserting my many many kilograms of unearned white male privilege and saying, “Let me offer you the guidance. Now let me show you the way to the stars.” I’m not completely comfortable with that. Guidance, I’m always a bit iffy.

Audience 4: I’m curious as a writer if you you’ve ever kind of encountered audiences who come from cultures very different from your own, and how may be encountering and interacting with them has somehow changed your own perceptions of what you’ve created.

Ellis: I mentioned I don’t leave the house much, right?

Audience 4: What?

Ellis: I mentioned I don’t leave the house much, right?

Audience 4: You don’t have to engage physically. There’s all these different ways to connect now.

Ellis: There was a TV show in Britain called The Thick of It, where an older politician is asked to engage with digital networks, the World Wide Web and blogs. And he described it as, “It’s the shit room.” And someone said, “What?” He said, “No no no. It’s the room and you open the door and they push you in and it’s full of people there to tell you how shit you are. [crosstalk] It’s the shit room. You opened the door.”

Audience 4: Oh no. Really?

Ellis: Yeah, don’t force me to go into the shit room, please.

No. Engaging with cultures other than my own…

Audience 4: Perspectives maybe is a better word.

Ellis: I’m sorry?

Audience 4: Perspectives might be a better word.

Ellis: Perspectives, yeah. Going back to unearned white male privilege, engagement on my terms to some extent is important for me to be able to do my work. So I do travel, I do go to other places. I always try to listen. I always try to learn. Whether or not that expresses in the work is for someone else to judge. I would suspect not perfectly. But I don’t disagree with the premise that that’s something I should continue to do and continue to try and do better. I don’t know if that addresses your question.

Audience 4: Oh I was just curious as an artist, you know, sometimes when I make something I learn more after I’ve showed it to someone. It’s another way to ask that question.

Ellis: Yeah, I’m nervous of the bubble. I’m nervous of just walking around as a traveling echo chamber. So I’m constantly looking for ways to try and punch through that and to learn how other people see things.

Slavin: I don’t know how long we should go, and somebody should give me a sense of that, or maybe you should, Warren, I don’t know. But this was a good question that came in over Twitter from Dave Press. “What is it about writing comics that lends itself well to writing prose fiction?” Which I think the larger question is what is the relationship between…

Ellis: Oh, comics is the worst possible training ground for writing prose fiction. It’s always a wrench going from one to the other. Because in a comics script I have to describe an image as completely as I can for the artist to be able to easily achieve that image. So it is very blunt, technical descriptions I’m trying to surround a thing, so that the image could be produced. But if you do that in prose fiction, the image lays dead on the page. In prose fiction you have to describe an image in broad enough strokes that that image can take life in the reader’s mind. Which means you have to elide exactly the details that a comics artist needs to achieve an image.

Slavin: That’s really interesting.

Ellis: So that is the first thing I have to learn and then unlearn as I transition from one to the other.

Slavin: You also—well I guess not with Normal but with Gun Machine and Vein, you delivered them whole, right. Whereas with something like like Planetary, you wrote over a ten year period?

Ellis: Planetary must’ve been ten years, yeah. Transmet was five.

Slavin: You don’t know where it’s going to go, or do you?

Ellis: I wrote the first draft of the last issue of Transmetropolitan somewhere during the first year of production.

Slavin: Oh wow.

Ellis: I always knew how that book ended. Planetary, I had an idea. But I didn’t have it nailed down until it finally came to it. Freakangels, again by about half-way through that. So I was at the eighteen month, two years mark, because that book is like nine hundred pages long. By about half-way through I knew how Freakangels ended. It very much varies.

Slavin: If you’re working on a project for like ten years, part of what you’re doing is you’re gaining feedback along the way. Does that calibrate anything?

Ellis: What’s more important than that, because the only feedback I’m really interested in is from my artist and from my editor. I don’t even read my own reviews. Because that would make me cry. But um…I’ve completely lost the thread of what I was going to say. Can you ask the question again?

Slavin: Just whether you…do you course correct over time?

Ellis: Do I course correct, yeah. The feedback I want is from the artist, as I say, and the editors. Course correction for me, because comics is so weird—a graphic novel, you’re writing, creating, and seeing produced one chapter every month over a period of years rather than just writing the whole damn thing and then releasing it. So you can see for yourself what doesn’t work as each chapter is produced.

Slavin: I course correct in any number of ways. I could see a storyline is going to go somewhere because that’s not working on the page the way I thought it would, so I can do something with that. I can change the way I write for the artist. I’m learning quite often— Even though I normally go into a job with a fairly deep understanding of what an artist is capable of and what their range is, as I start to work I learn more. So I change the way I write for the artist as I go to better fit for them so it’s easier for them to produce work.

Big part of my job is trying to make the artist look good wherever possible, you see. Because at the end of the day the first thing someone sees when they open up a comic is not a line of dialogue. The first thing they see is an image. So it’s my job to make those artists look as good as possible.

Slavin: But when you work on movie projects, you can’t have anything near the same control.

Ellis: No. That is again really broad strokes. Because you’re trying to charm a director with the potential of a beautiful scene. But I’m also working on Castlevania, which is an animated TV show. Which actually hews a little closer to comics because I can create having looked at the animators’ work, having looked at their environmental paintings, and the way they do setups. I can create things that will work very specifically for their strengths. I will try to delight them, so that I can make them look good.

Audience 5: Hi. I want to talk about Transmetropolitan for a hot second. Transmetropolitan is this world where kind of the possibilities of human expression and identity are basically exponentiated through the ability to alter your body and your appearance. And I think in the real world people often think of the arc of socially acceptable human expression and identity as just like increasing over time. And maybe to the point that we see in Transmetropolitan. But also in Transmetropolitan you show these themes of dystopia, often through these identities clashing with one another in really strong ways. Can you talk about I guess your decision to have a lot of the conflicts or the conflicts in the city in Transmetropolitan being driven by that identity? Do you think that’s kind of…how it relates [inaudible]

Ellis: First of all I would ask you to bear in mind this work is twenty years old, alright.

Audience 5: Yeah, yeah.

Ellis: This is not current. This does not have the reflexivity of current-day fiction on these concepts. The identity politics are, to be charitable, primitive. So what you’re seeing is what I was seeing in like ’95, ’96, ’97 when I started writing this book. Which was simply the way the streets had changed through the last ten to fifteen years of my life in 1980. The only people you saw with tattoos on the streets of my town were old sailors and old bikers. And you didn’t see people in piercings.

By 1995, half of everybody you saw had a tattoo, and you saw people in business suits and piercings coming out of the civil service buildings. And so what you’re talking about is me really just illustrating and extrapolating from the nature that our streets change from things originally perceived as transgressive to eventually mainstreamed. And that’s all I’m really talking about in that point. It wasn’t a searing insight.

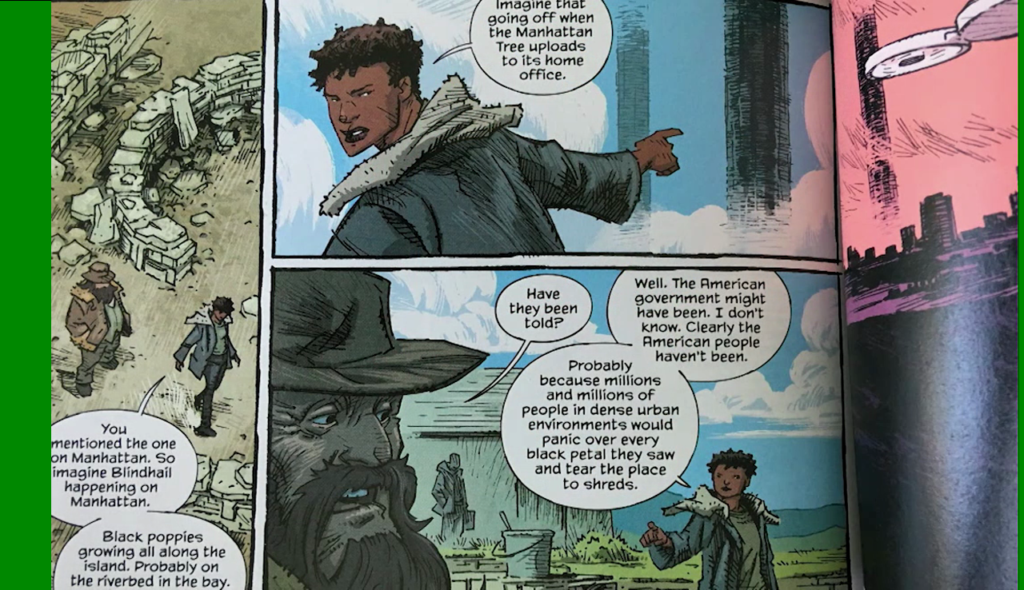

Slavin: If there’s not another question, I have one last thing I would want to ask about, which is— This is Trees, which is— So what’s the story with Trees? There’ve been two…

Ellis: There’ve been two graphic novels, and we’ve taken a break because they’ve really hard to do, and because I’ve been writing the television adaptation for Tom Hardy’s production company Hardy Son & Baker in partnership with NBC Universal.

Slavin: Can you sort of tell us a little bit about what the idea is of the series?

Ellis: Ten years ago, in the time of story, somewhere between fifty and seventy vast alien structures land on Earth. Some of them land on the cities, just spear through cities. Some of them land in remote spaces. There seems to be no rhyme or reason to it. And they land, and then nothing happens. They make no contact; nobody comes out; you can’t get into them; they’re impervious to weaponry, communications, scans, you name it—they’re just there.

And the story, such as it is, starts ten years later when through what Marshall McLuhan called the rear mirror effect, these things have become normalized. They’re just part of the landscape. And yet, there’s only so much you can normalize— And even though we do normalize them in order to function around them, they still exert some kind of pressure upon their environments, and the stories in the books are about the people who live under these things that are called trees, and the pressures that the trees exert.

Slavin: I was really struck, you know. There’s this one where she says, “Imagine that going off when the Manhattan tree uploads to its home office.” The idea that these are in communication with one another. It’s interesting to me me just because I’ve become aware of Suzanne Simard’s work. And I don’t know if you’ve ever come across her, but she’s at the University of British Columbia. She’s a forest ecologist. And she’s just been studying how trees communicate with trees.

Ellis: Rachel Armstrong was working in that region, I want to say five years back.

Slavin: Yeah.

Ellis: I did a thing with her in Eindhoven where she was talking about how trees communicate and how trees compute.

Slavin: Yeah. And share resources and even what would in an anthropocentric narrative would be…they prioritize their young.

Ellis: Yes.

Slavin: Like fir trees will take care of fir trees before they take care of a pine tree, or whatever—the sentence doesn’t make sense. Anyway, but just this idea that there are scientists who are working right now to really see the world as it really is, which is also then this thing that you’re also sort of proposing.

Ellis: Yeah.

Slavin: For me that’s the— I don’t know if you were drawing up from their research, or whether you’re just converging on it, but—

Ellis: Yeah, a lot of these things I tend to think of as composting. I just collect as much as I can. It just goes into the pile back here [indicates back of his head] and rots down and starts to stink and to catch fire from time to time. And then when I’m really lucky, one thing in there will plug in to another thing, and that constitutes an idea. And that just rises out of the heap. But you’ve got to keep the heap fed. You’ve got to keep piling shit on in the pile at the back there.

Slavin: Yep. Fermentation helps, also.

Ellis: Fermentation is crucial.

Slavin: So on that note, if no other. Warren, thank you so much for being so generous with your time and your thoughts and your wisdom. Thank you. And thank you to all of you for your questions. And…thank you.

Ellis: Thank you.

Further Reference

Archive page for this presentation at the Media Lab.