Ethan Zuckerman: So, welcome back from lunch, everyone. If you attend a lot of conferences, as I do, you know that this slot immediately after lunch is the slot that’s really hard to speak in. Because everyone just wants to be having the conversation they were having over lunch. Everyone’s in a food coma. And so we thought we would complicate matters by taking both the hardest slot to fill in a conference and then taking on perhaps the most fraught topic that we’re going to work on today. You’ll remember that when I started this I said that part of our goal in all of this was to make sure that we made everybody in the room uncomfortable. My guess is that this topic is going to get a lot of people on that front.

One of the big things that we’re going to talk about here is paraphilia. We’re going to talk about sexual deviance. We’re going to talk about the problem of people whose sexual desires lead to attraction to children, lead to attraction towards violent sex, lead to sexual transgression in one fashion or another. To be really clear, we’re not showing explicit imagery in this panel. But this is a panel that may well be triggering for people. If you’re a survivor of sexual assault, if this is an issue that you know that you have a hard time with, it’s a beautiful day. I would encourage you to enjoy the balcony, to have another conversation, to take a break for about an hour.

But we’re going to try to deal with this very challenging topic because it’s a topic that has lots of real-world implications. There’s something like eleven thousand registered sex offenders in the state of Massachusetts. There are thirteen hundred at the moment serving time for sex crimes. Perhaps most challenging, there are several hundred people in the state who are in indefinite civil confinement. And the reason for this is that these are sex offenders who have completed their prison sentences, but there are concerns about releasing them into the general population because there’s fears of recidivism. And Professor Arkin and I have been really trying to research this question of what are the statistics on recidivism? What’s the rate on this? We, just doing some Googling over dinner last night, found numbers ranging from 10% to 50% for convicted pedophiles, which suggests more than anything else that there just isn’t a ton of research on this. When you have a range that wide, it suggests that we know very little indeed.

One thing that we do know from research in this field is that most people who are afflicted with pedophilia are actively trying to fight these urges. And when they talk to therapists, what they end up saying is that they’re trying very very hard not to act on the urges that they’re suffering from. And they do describe it as “suffering from.” And so the topic that we’re looking at, which is really this question of whether there are ways of treating paraphilias with computer imagery, with virtual reality, possibly with intimate robotics (which is a term that I hadn’t heard until the other day), this is the topic that we’re going to try to take on here. So, it’s a challenging topic. We’re lucky to have an incredible set of people willing to take on this issue here with us on stage.

To the very far side of me, my friend Dr. Kate Darling. She’s a legal scholar who looks at a wide variety of subjects, but lately has been looking at sort of real-world implications of human-robot interactions. And not looking to the distant future and Asimov’s Law, but really looking at right now. What are we doing in our interactions with robots? How does this work? How do we interact with one another?

Slightly closer, my colleague and friend Christina Couch who works in the Comparative Media Studies department, is also an accomplished technology journalist and freelance writer who has written on this question of computer imagery, virtual reality, and how it fits in with questions of paraphilias.

And then immediately to my left, Professor Ron Arkin from the Georgia Tech College of Computing. He’s someone who’s done extensive work on robotics and robot ethics. And while he’s normally someone that we bring to the table to talk about questions like autonomous killer robots, he’s also someone who’s going to talk with us on this subject as well. But since Dr. Darling put this panel together, she’s going to lead us off.

Kate Darling: Don’t worry, I don’t have any slides. So as Ethan mentioned I’m a researcher here at the Lab, and I wear two different paths. But something that I’m very intensely interested in is the field of human-robot interaction, so the study of how we behave around robots. And I would say that the single most fascinating thing to me about robots is that people will treat them as though they’re alive.

Now, of course everyone knows that robots are just machines. They’re just programmed to do things. But subconsciously when we interact with robots, we treat them as though they’re alive. And for many of us who work in human-robot interaction, a lot of us believe that this isn’t just a matter of people getting used to a new technology that they’re unaccustomed to but rather something that’s biological. So, our brains may be biologically hardwired to project intent and life onto any movement in our physical space that seems autonomous to us. And there’s a whole body of research that is documenting how strongly we respond to the cues that these lifelike machines give us.

And the reason this is cool is because it gives us this really interesting lens through which we can study human psychology. So for example, I did a study here at the Media Lab with Palash Nandy where we found that people who have low empathic concern for others, they will treat a robot differently than people who have high empathic concern. So, we can use robots to measure human empathy. And in this context, robots— I mean the fact that people treat them sort of like a living thing makes them potentially a really great tool to study and explore sexual behaviors and sexual urges and try to understand those better. And that in itself is very useful as a research question since we know so little about this.

But there are actually more questions that I’m interested in. So, one thing that I want to know is not just can we measure or observe people’s behavior with robots, but can we change it? So, could we use robots therapeutically to help people manage their behavior, control their urges, that type of thing. And another question I have which I think is very important is, once child-size sex robots hit the market, which they will, is the use of these robots going to be a healthy outlet for people to express these sexual urges and thus protect children and reduce child abuse? Or is the use of these robots going to encourage, normalize, propagate, that behavior and endanger children in these people’s environments?

And we just don’t know the answer to this. We have no idea what direction this goes in, and we can’t research it. Because aside from the fact that there’s this incredible social stigma, of course, to doing work like this or even talking about it, and not to mention the lack of research funding, there are also reporting requirements in the United States that make it virtually impossible to work with people who haven’t already been convicted of sex crimes and often have been in jail for them. So you have a very difficult and very skewed sample of the population that we need to be studying.

And I understand why people want reporting requirements. But I do wonder whether they’re doing more harm than good in these cases. Because as much as people want these sexual urges—the urges, not the act—to be a moral failing, they are a psychological issue, and if we really care about helping children we might need to be a little bit more preemptive about this.

So I’ll just finish by saying that courts all over the world have been struggling since the early mid-2000s with the question of virtual child pornography. So, computer generated images that aren’t actual children. Courts don’t know what to do with these because no child has been harmed in making them. And the technology that brings this to a more extreme, more physical, more real level, is on the horizon. And while high-quality sex robots are not actually coming as quickly as many people think they are, they’re coming more quickly than society’s willing to have this conversation. So, I’m very grateful to be here today in a room full of really smart people who care about making the world a better place to discuss this very sensitive, very difficult, and I think very important issue.

Zuckerman: So Kate, I just want you to unpack something a little bit, because it went by very quickly. Child pornography ends up being prohibited for at least two reasons. One is that we don’t think such a thing should exist, or that’s been a societal decision. But the more important reason in many ways is that a child is harmed and exploited in the course of producing these images. 3D modeling, the ability to create digital imagery, starts raising this possibility of virtual child pornography. What’s US law’s take on this thus far, and are there other jurisdictions—because you’re not just a lawyer but an international legal scholar—are there other jurisdictions that have ended up handling this issue of virtual child porn differently?

Darling: Yeah. So, it’s complicated. In the United States we had, I think in ’96, an act that forbade computer-generated images of children, and the Supreme Court struck that down in… Do you remember when it was?

Christina Couch: I think it’s 2002.

Darling: In 2002, the Supreme Court said that there was a fundamental free speech issue if you’re criminalizing just computer-generated images and not an act that actually harms people. And so they ended up striking down two of the provisions of this act. Since then, there’s been a new act called PROTECT that was passed, which now prohibits computer-generated images, or cartoons or whatever—it actually explicitly says cartoons—but only if they’re obscene. So they’ve kind of shifted away from the child piece towards obscenity, which is a very convoluted, very complicated thing that’s not well-defined and kind depends on community standards. So the US has struggled because we have such strong First Amendment rights.

Other countries have flat out banned this, like Germany, I believe. And then other countries like Holland have just struggled with cases where they want to ban it, so they find some other reason. Like there was a video that was teaching young girls to perform fellatio, and they ended up criminalizing that based on the fact that it was targeted at young girls and trying to teach them improper behavior or undesirable behaviors rather than the fact that it was a cartoon that depicted girls. So it’s very complicated and I think courts haven’t figured out a good way to strike that balance.

Zuckerman: So, I think we’re going to get back to this question of what the legal status is, but we’re also going to be wrestling with this question of what is exploitative of of children, and what is something that’s illegalized because it’s uncomfortable, it’s socially undesirable. And how does that work in with questions of what might be therapeutic, what might be helpful. But I want to pass it to Professor Arkin.

Ron Arkin: I do have slides. I gave a talk just recently in Italy, a paper written jointly with a colleague of mine from Georgia Tech, a philosopher named Jason Borenstein. But I’m not going to give that talk here. Just to let you know that I have a few things I’ve reused from it.

And I’ve been involved quite sometime. I’ve been a roboticist for close to—maybe even over—thirty years as well. And I do work in sex, lies, and violence I guess is the best way to describe it. There’s plenty of money, in some ways, for dealing with lethal autonomous weapons systems. And the US department of defense doesn’t do that specifically, but I work on ethical aspects of that. But that’s neither here nor there for today.

I also, supposedly, according to—that was New York magazine—taught robots how to lie at one point, and that got us a small piece on The Daily Show, among other things as well in terms of the questions of what are you doing with these sorts of things. But we weren’t forbidden, and we’re still doing work in robot deception. But I’m not talking about that today.

What I am talking about is a place where there is no money to be able to get this kind of research, which is in the broader aspects of this. And so this notion of intimate robotics (Which actually is an outgrowth of work that Genevieve Bell at Intel did many years ago in an ubicomp conference on intimate computing. I know there was some work here in the Media Lab also that was portrayed in that case.) deals with more than just sex. Sex toys and sex machines have been around since man and women have been around as well, too. That’s nothing new. That’s not what I’m worried about. And this is my second greatest concern with the impacts upon society. The first again is the lethal autonomous weapons systems which is happening now. This one is about to happen or is happening as we go. But I worked with Sony for ten years and Sony Aibo. On Qrio as well, which were these small platforms and have patents in robot emotions as well.

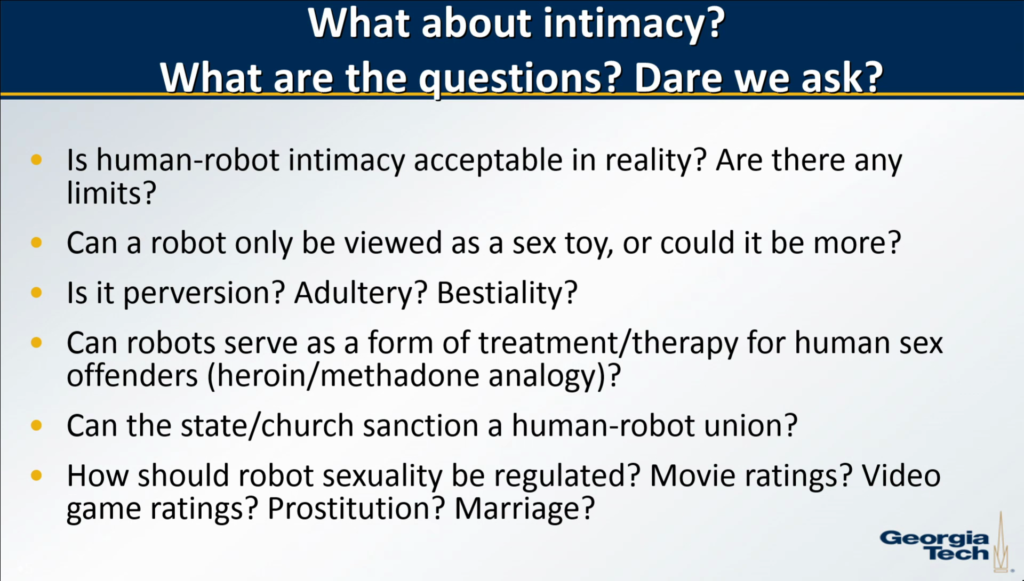

So the question is, we know how to (and you guys know as well, too) at least many here, know how to make people fall in love with these kinds of platforms. Now for a small dog… You can talk about pet psychotherapy and other aspects as well to it, there are clearly beneficial roles. But what if we start doing it where we cross this proxemic boundary. Instead of socioconsultive space or a familiar space, but we get into the intimate space where these systems start to engage with us more and more deeply?

And so there are many questions which I share. I spend a week with my undergraduate class in robots in society talking about this particular topic, and these are the kinds of things. I mean, it’s not just a question for sex deviants. Do you become a deviant if you engage in sex with a robot? I mean, what does it really mean if you actually start getting involved with this hunk of metal and plastic and getting it on? That’s an interesting question itself. The points that I’m also interested in the context of the premise for this particular session, can it serve kind of like methadone for these sex offenders, pedophiles, and the like, as well? Will it help to sublimate their desires? We don’t know. This is a research question, and it needs to be explored.

And the cost if we don’t explore it is intolerably high. Whether the recidivism rate is 10% or 50%, that’s 10% or 50% too much. And the point is if these people, which we choose to do as a society, are released back into society, there will be more victims. Let’s just face that fact. And we need to find a way to cope with that. And this is potentially one. We don’t want to make the world worse, either, as a consequence of that. So there’s a lot of issues, just as there are with weapons systems, associated with these sorts of things.

So, this whole notion of talking about this is just in many cases off the board. There was a love and sex with robots workshop at a computing entertainment meeting that Malaysia came and shut down that conference as well. They called it ridiculous, but I think it was more than just ridiculous from their perspective, it’s taboo. It is completely taboo to talk about these particular issues. And I thank you for this particular forum to start to raise these particular questions with this audience and with those that are not in the room as well.

The point is, many of you here are familiar I’m sure with the Uncanny Valley. That’s probably nothing new to you. But we are starting, some people, and I’ll show Ishiguro’s work as well, that come out of the valley of zombies at the bottom of that particular chart. Interesting, I was thinking about that the other day. It’s a two-dimensional chart. One deals with behaviors, and the other deals with the morphology or the shape or the appearance of the robot. The appearance we’re getting pretty good at, although not tactile and not with temperature control and other things like that as well. But behavior can still be a problem. And the bottom of that is kinda like zombie-like, and so necrophiles might be down in that particular level, if we really want to talk about the breadth of abuse that occurs within humanity.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cy7xGwYdRk0

This is Ishiguro’s latest work. I’ll have the pleasure of visiting his laboratory in September, which I have not done. These are not sex robots, but he does have extensive funding from Japan to continue this particular work, and he has a company as well to deal with these particular kinds of platforms. It’s quite remarkable.

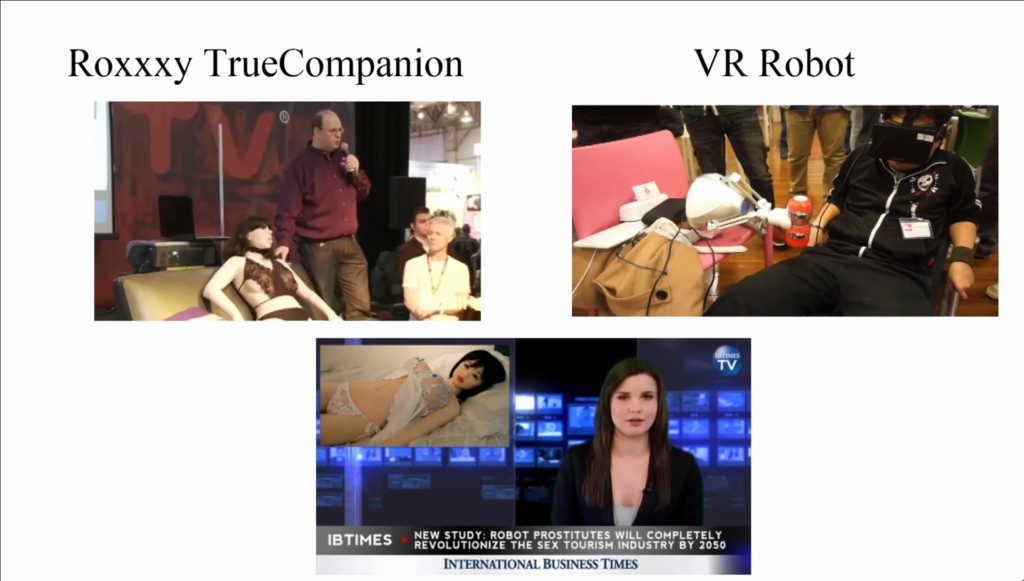

In the interest of time I will just move ahead and show you what the real state of the art is commercially, which is kind of…not there. Let’s take a look at that. That’s Roxxxy over there, which actually supposedly—supposedly—has AI because it can chat with you and tell you the baseball scores and other things as foreplay. So that’s the notion of that particular robot.

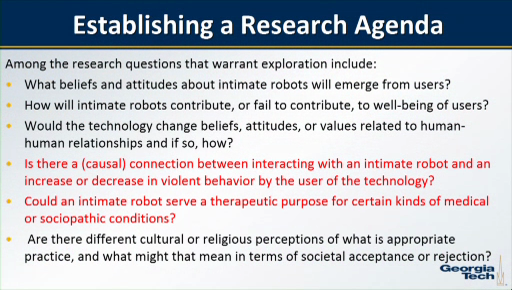

The VR Robot as you see has a VR head and it has an arm which is doing what you think that arm is probably doing in that case. And other aspects as well deal with papers and others have been considered how the prostitution industry will prosper through the use of robot dolls, and many robot lovers. And many say this is a good thing for women because it will free prostitutes and the like. And others are saying it’s a bad thing because it’ll end the age-old profession. So, I don’t have a position on that. I’m just trying to tell you what’s coming down the pike.

Now this was a good article that was written by The Atlantic a while back. There is a company in Japan. I think it’s [Trottla], something like that. I’ve actually been in contact with the guy. I asked him if I could use some pictures for this talk and I decided against it because, for the very reason I might end up being accused of child pornography, of having pictures of robot child dolls on that. But his motivation, reportedly, and in the email message, is that he wants to help pedophiles. He wants to both reduce the urges, and he wants to help the victims as well. So, this company can lead to a variety of different things.

One, if you look at the right side there, one of those robots was delivered to Canada. The guy was arrested and is awaiting trial. So what is…is it a crime? I mean, this is not just a computer graphic image. It’s not necessarily based on any real child. But…what do we do with this? And so if you talk about methadone again, that’s prescription-oriented. Maybe there are certain people that would warrant this particular case. And it would, in my estimation, warrant strong regulation and control and not just be available for the general public. That to me would be the wrong answer.

But even moreso, there is the— Kathleen Richardson has started the Campaign Against Sex Robots. You may have heard about the campaign against killer robots. Well this is kind of modeled after that. Not quite as big. But they had a statement on the production of child sex dolls, and they said basically Japan should shut down this particular guy. And we shouldn’t do it. It’s a preemptive ban. That’s what the killer robots, as well. We don’t want these kinds of robots. And so if you believe that, there’s an organization which you can sign up and join.

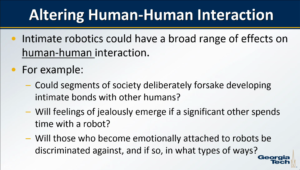

My bigger concerns are how it affects our relationships with each other. Having these devices potentially… And you’ve seen shows like, maybe some of you saw the TV show, I don’t even know if it’s been renewed, Humans, which had a robot which had an adult mode which the husband found and turned on and caused kinda trouble in the relationship over time. But Ex Machina, of course. And Blade Runner. I mean, we see this all time in Hollywood. But we can’t talk about it in the real world, which is really strange in some ways.

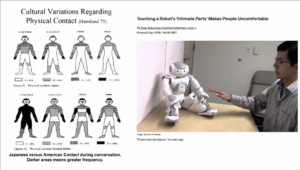

So there’s these notions of how the future is going to be affected by these sorts of things. One scientific study came out of Stanford just recently. And it talks about people becoming aroused if they touch a robot’s private parts. This is a generic Nao robot. I’ve got two in the labs. And I used to pick it up at any place which I could get a hold of, but now I’m a little concerned if I do. But these are the kinds of platforms that can be used to show that people, if you’re told it’s a private part such as, what does it say? “Please touch my buttock,” in this particular case, people might feel uncomfortable, and they reported this. But they reported this, in one of the most obscure conferences I ever heard of. And that’s probably because it’s not ready to be submitted. I could not find an attribution of a funding source, either. So I’m not sure it was necessarily funded. I could be wrong on both of those counts, ultimately.

And again, working with Sony, we started to learn the differences of the cultural variations of where it’s appropriate to touch people and different types of friends and others from say, the East versus the West. And so if you’re a Japanese individual, you would mind being touched in certain places that Westerners might not, and vice versa. These are the sorts of things that a robot designer would think about.

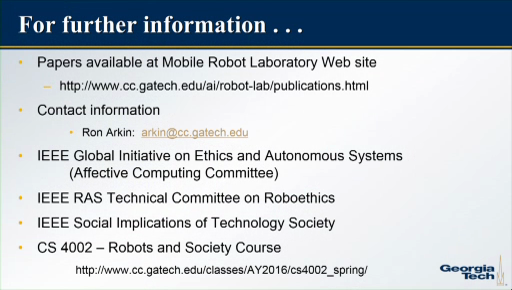

So the goal I have, basically, is to establish a research agenda. The two questions that I mention over here…the red ones are the ones that really deal with the question here. Can we increase or decrease the violent behavior—uh, we don’t want to increase it—but will it increase or decrease the violent behavior by the user of the technology? And can it be used for therapeutic purposes for different types of potential sociopathic conditions?

So, the real issue from my point of view is that we need to understand this because of the human-human relationships that could potentially be affected by it. And I would contend that we have an ethical, and yes even moral obligation according to our local codes here, to investigate this. And if we don’t do so, we do so at our own peril. So, I will stop with that. And if you’re interested in some other information as well, you can find it at that source. Thank you very much.

Zuckerman: Ron, let me just ask one quick question before we go to Christina. When we were looking at your slides and sort of talking this over yesterday, one of the things that you were suggesting is that as intimate robots become more common, that’s likely to be a relationship that we have to deal with societally. People who end up deciding that they have robots primarily as their sex partners, that may become an identity. There’s a good chance that that identity will end up being stigmatized.

This question of normalization also raises this question of, if people are regularly relieving urges with child robots, is that also a normalization of behavior? And is that a danger that by normalizing that behavior, regularizing that behavior, that this becomes less of a taboo and in some sense this actually may become more dangerous in terms of pedophilia acceptance?

Arkin: The real point here is we just have research hypotheses right now. We don’t have answers to those particular questions, and they definitely need to be investigated. The point that you mentioned earlier is the fact that we have a relatively small number of people— And if you’ve ever seen, there’s a movie called Guys and Dolls? It’s not the movie Guys and Dolls (1955), but there’s another movie Guys and Dolls (2002) which talks about people kind of like Lars and the Real Girl, who actually are…in some form deep attachments to these particular platforms.

I expect as we get more sophisticated platforms, the sector will rapidly and significantly expand as well. How that profoundly affects society is an unknown question, but we don’t want to wait and be reactive to it, we want to be proactive, and that’s what I’m trying to encourage here, is proactive research into this space. Because hopefully as you’ve seen in some of those videos there, it’s happening. There’s a lot of money to be made if you get that even close to right in the near term, as it happened with digital video devices and the Internet, which are major purveyors of pornography. These kinds of things will find a home and a market and will be sold. And right now it’s happening in places like that, and not under appropriate guidance and ethical review. We need to consider this significantly so we don’t make the kinds of mistakes that you’re talking about.

Zuckerman: Ron, thanks so much. Christina, can I get you to contribute on maybe the visual imagery side of this discussion as well?

Christina Couch: Hi. My name is Christina Couch and I am a freelance science writer. So, specifically what interests me is technology, psychology, and kind of the intersections between those two things. So I’m really interested in things like how our feelings and thoughts and desires shape how technologies are designed, and in turn the impact that those technologies have on our psychology and neurology and the way that we interact with each other.

So, what got me interested in the topic of this particular panel was about a year ago I was working on an article about therapeutic uses of virtual reality. So I was interviewing researchers who are using virtual reality to treat things like post-traumatic stress disorder, depression, anxiety, phobias, addictions, all sorts of things. And I stumbled across a guy named Patrice Renaud, who is a researcher at a maximum security psychiatric facility in Montréal. And Dr. Renaud is actually using virtual reality to study pedophiles, specifically pedophiles right at the point of arousal, which historically has been an incredibly difficult thing to do because in order to have a study subject be right at that point, you need some sort of stimuli to get them there. And typically that’s images or audio files which come with these very very valid moral and legal issues attached to them. Super valid.

So Dr. Renaud actually started researching sex offenders in 1994. And at that point he was using predominately audio files to kind of do this research, and he wasn’t really getting very good results. He was having a hard time getting enough data. When he was conducting his original experiments, his team actually published a paper on which showed that even when they absolutely knew that a study subject was a known pedophile, they could not evoke a physiological response in about 40% of cases, using just audio files.

So, fast forward a few years when virtual reality becomes a little bit more accessible. Dr. Renaud started building virtual environments that came with…fewer legal and moral issues attached. And he actually found that he was able to get a lot more data. And not only was able to get a lot more data, but he was also able to actually find a difference in the physiological response when a pedophile is aroused versus a non-pedophile, and those differences are mainly in motor and eye movement.

So when I heard this I was really sort of blown away, because it with all the media that we have on sex offenders and recidivism rates, etc., etc., I was really surprised that it is incredibly difficult to study this particular group of people. And at the same time I was also really surprised that of all the tools we have for studying criminology, virtual reality was kind of a key piece of technology that opened up this particular study.

So at the same time that we sort of have these new research tools, or at least potential new research tools coming out, we’re also in the middle of somewhat of a shift in terms of how we think about child sex offenders. And at least a small part of that is due to groups like Virtuous Pedophiles. They are a support group specifically for pedophiles, run by pedophiles, and they’re designed to prevent people from acting out. So it’s a group that if people are feeling those types of inclinations, they can go to this group and try and find tools and resources to prevent acting on their impulses.

And they’re not actually the only group of their kind. A project of sort of a similar flavor that’s been going on for a longer period of time is in Germany. It’s called the Dunkelfeld Project, and that is a voluntary confidential treatment for people who are pedophiles, specifically designed to prevent them from acting out.

So, kind of at the same time that we have this potential for new research tools and we also have accessibility to a population that historically has been much more difficult to access, typically when those two things come together you see a lot of research coming out right at that intersection. But for this particular topic, there are still really significant barriers to doing that research. And I’m kind of hoping that our fellow panelists who are actually on the ground floor of doing research can talk about what some of these barriers are.

Zuckerman: Christina, thank you so much for that. Can you talk just a little bit about why this program’s been able to get off the ground in Germany? That this therapeutic program in Germany that’s allowing people to come forth and actually seek treatment, what are the barriers against that in the United States at this point?

Couch: Well, I mean we still have, like Kate mentioned, the reporting issues. One of the things with the Dunkelfeld Project is that there aren’t reporting issues, so people can come in and be completely anonymous. From what I understand they just get a digital—a number. So you’re actually just… There’s no names involved whatsoever. So the reporting issues are a lot different.

And also they have a lot more support. At some point there was a push by some group of people (all the qualifiers in the world here) to actually get this thing covered under health insurance. Which is mind-blowing to me. I think you would have a really tough time with that in the United States.

Zuckerman: It’s interesting. In the US, something that is becoming more common is the option of chemical castration as a response to pedophilic urges. And there are cases, at least in Massachusetts, where Lupron, which is the drug that people end up using for this, has been covered under prescription insurance.

What’s interesting to me in some ways is the idea that this is a treatable condition. And that what we’re seeing are essentially these sort of voluntary groups trying to help people who self-identify as pedophiles not act on urges. And to pick up Professor Arkin’s notion that, is there a possibility that this is the methadone to heroin? That having, whether it’s virtual reality imagery, whether it’s intimate robots, there’s some way of sort of preventing this. It seems like the big shift that we would have to have first is an understanding of paraphilias as a medical problem, a psychological problem, rather than a moral failing.

Kate, can you talk a little bit about how the legal system makes that change? So you know, there was a moment in time where homosexuality was moral failing and crime, and then became disease. And then over time has become normalized. How does law deal with changes from something being ethically unacceptable to being medicalized?

Darling: Well, I mean the law in the case of homosexuality was really kind of following popular culture and not the other way around. So there was a massive shift in popular culture, probably started with TV shows having a lot of gay and lesbian people who were open, and that kind of seeping into the public consciousness and becoming an okay thing. And then the law kind of came afterwards.

In this case… So, I just saw the documentary Untouchable that premiered at Tribeca, which is about this issue and how the legal system deals with it. And it was shocking to see how—I think they were looking at the case of Florida, but… If you throw the word “pedophilia” into any type of policy or legal debate, all the politicians are immediately like, “Oh, this is a law that’s going to crack down pedophilia? I have to vote for it.” And there’s no way that they can have any sort of conversation about any of these things because it’s such a… The topic just raises—understandably raises so many emotions in people that there’s no rational conversation to be had.

And I was shocked when I was doing some online reading for this panel at how people who had written New York Times op-eds about perhaps new methods of treating this, they were getting—like, there are YouTube videos about them where people are saying that they should be slaughtered and whatnot. Just for suggesting that this could possibly be an illness rather than a moral failing. So it’s very hard and I think the social conversation has to happen before the legal conversation.

Zuckerman: Do you think there’s something in German society, which you know at least something about, that is different in sort of understanding— And just to be clear, in my previous question I was not in any way trying to suggest the medicalization of homosexuality as a problem, nor was I trying to suggest the normalization of pedophilia. What I was trying to suggest was there are shifts where we bring something out of a morally unacceptable territory and then deal with it as a different issue. For instance dealing with it as a medical issue.

It sounds like Germany around pedophilia has figured out how to make a shift into dealing with this as a medical and psychological condition. And you’ve just pointed out, in the US we’re willing to pass laws that literally make it impossible for people convicted of child sex crimes to live within a state. They’re actually constraining physical space in which sex offenders can live so narrowly that there are huge swaths of for instance the state of Florida where people can’t legally live. How does that shift take place?

Darling: Well, I feel like continental Europe generally has a very different attitude towards anything sexual, really. They’re less Puritan than American society. I mean the Germans in particular have always been very practical about this sort of thing. And for example, I believe you had some of the German government visiting your lab one day, and they were from the Green Party. And they wanted to instate I think a flat tax on downloading files from the Internet, and just get rid of copyright law, and just tax people on what they download.

And I was like, “Well, how does pornography fit into that?” And they didn’t bat an eyelid. They were like, “Of course that,” and they explained how it would work, and they were like, “Yes, that’s like any other file.” I just couldn’t imagine having that conversation with politicians in the United States. So I just feel like European culture is a little bit more you know…less up in arms and screamy about this topic, generally.

Zuckerman: Ron, you were ending your remarks with basically the outlines of a research agenda. You are a roboticist. You are a robot ethicist. What’s stopping you?

Arkin: Funding. That’s the primary question. Actually, the first time I raised the topic of pedophiles being treated as methadone was maybe ten years ago. I can even remember the meeting I was at. But of course the press was present there as well, and that got articles of course because that’s what the press does. And hopefully we won’t be quite as sensationalistic as an aftermath of this entire meeting as well.

But I did get an email from a social worker who had offered to me twenty or thirty—I can’t remember the number—human subjects. Sex offenders that they were working with. And they said, “Here are some people that we can provide for these studies.” And you know, I just had to wistfully smile and say, “Okay. Where am I going to get those resources from?” Do I want the equivalent of the Golden Fleece Award in the National Science Foundation or NIH—if they did fund me—to have the senators come out and parade this research as robots for sex? You know, that’s the end of that discussion as well.

The only hope, I would contend, are foundations. Foundations are one possibility. And there was a well-known foundation which I will not name here who I had a champion at, who discussed a proposal I had. And this wasn’t even a concrete proposal to do the research. This was just trying to deal with ethical guidelines and like. And they evidently had—based on what my champion told me—had discussions of this and others over a period of two days, and nothing came from that. So if it’s not from foundations, I honestly don’t know where the funding is going to come from.

Zuckerman: Christina, you’ve had the opportunity to talk to people who are doing therapy in this space who are really making these sort of interventions to try to figure out whether paraphilias are treatable, whether people can get help with their urges. What are people’s motivations for doing this work? Clearly this is work that’s incredibly difficult. There’s huge barriers associated with it. There’s enormous social stigma associated with it. Do you have a sense for who the people who are doing this work are, and to what extent they’re able to communicate this work and perhaps start working on norm shift on whether there are ways that we can deal with these issues as a disease rather than moral failing?

Couch: I don’t know that the landscape of the research coming out is big enough to draw any type of generalizations. I mean, as far as I know, I only know of two researchers that are using virtual reality in anything dealing with this. And maybe that landscape is bigger than my scope of knowledge, but it is small to begin with. And so it’s tough to draw any sort of generalizations about who the people are who are researching, or what challenges they’re facing, because the field is tiny. So I don’t know how to answer that, unfortunately.

Zuckerman: Yeah. In talking with the two that you’ve worked on, is there a backstory to how they got involved with this work?

Couch: I’m not sure. I’m not sure what Dr. Renaud’s backstory is. I know that he had been studying sex offenders for years prior to using virtual reality. I really think that for him at least, the problem of not being able to get usable data was forcing him to look for any other means of finding it. So, I’m not sure.

Zuckerman: So, I want to open the mics. so if anyone feels like asking a question please come on up.

Kate, I just want to put one more question to you, because I know that in many ways you find yourself sort of taking on these issues as they’re immediately sort of emerging in the space. Dr. Arkin put a number of possible issues on the table that happen around intimate robotics. What do you see as the key research questions that’re not necessarily around pedophilia or paraphilias? As an active researcher in this space, what do you find yourself sort of looking at around the questions of intimate robotics and these sort of collisions, as you described it? What do you predict needing research in that space?

Darling: I mean, my main research interest is how do our interactions with robots affect our interactions with humans. And I’m very much a fan of the harm principle, where if our interactions with robots end up leading to harmful interactions with other humans, then that’s a bad thing. But we also have no idea whether any of our interactions with robots are going to lead to any of the consequences that people are concerned about. So I think that’s incredibly important to study in intimate robotics in particular. And…what was the other part of your question?

Zuckerman: It was really that question of, as an experimentalist in this field, as someone who’s sort of looking at designing research in this space, are there things that you’re thinking about studying around this? Are there things that you know people are actively studying around intimate robotics that’re going to help us answer some of those questions? Whether it is questions about harm or whether it’s questions about how human relationships are transformed? I don’t know if you want to talk about any of your robot harm research within this, but…

Darling: I mean, our robot harm research was looking at violent behavior towards robots. And basically we’ve only gotten to the point where again, we can observe the behavior, we can measure the behavior, but we don’t know whether interacting with robots changes your behavior towards people. And I think that’s really the key question. It’s a very difficult question to research. And particularly in the area of intimate robotics, with no funding and the social stigma, I’m worried that it won’t be addressed at all. And I would be interested in doing it, but again like Ron said. I mean he’s a big name in social robotics, he can’t get the funding to do it. How are any of us going to?

Zuckerman: So, we’re going to go to a question first from the mic in the middle. Let let me just say something that I probably should’ve said earlier in this conference. It’s something that I like to say at academic conferences. Academics in many cases have forgotten what a question is. A question is not a statement, it is also not a speech. It is an interrogative. You can tell that it’s a question because usually someone’s voice rises at the end of it?

And if you have a test of whether this is a question or not, let me first say that “This is what I think. What do you think of what I think?” is not a question. A question is something that someone on this panel in theory could give a novel answer to. So with that in mind, if you would introduce yourself and put forward a question, that would be great.

Sheila Hayman: Well, that was a bit daunting.

Zuckerman: Not you specifically.

Hayman: I’m Sheila Hayman. And in the past three weeks, I’ve had to get used apologizing for being British. I would just like to say in this context that I shall be campaigning for a return to absolute monarchy on the basis that the Queen is the only person with a track record, the authority, and the public trust to actually repair the damage that’s been done. Thank you.

So, in defense of continental Europe and its culture, I have a bit of experience of the Quakers’ work in this field. As you know, the Quakers were some of the first people to start visiting people in prison, and they’ve also been working with sex offenders. Because one of the things that worries me (and this will become a question, don’t worry) about the the direction of this conversation is that all these technologies seem to me to be further sequestering and isolating the sex offenders from human society. And that surely, as you said at the beginning, is something that they’re trying very hard to get over. They want to be integrated with our society. They want to be part of it. And so my question is, do you think that it is possible in this country to propose—I think you sort of started to answer it—a system like that, whereby there are groups of people who are actually voluntarily engaged with pedophiles and sex offenders on the basis that they are humans too, and that we shouldn’t treat them even worse, necessarily, that we treat violent criminals?

Zuckerman: Terrific. Thank you. Christina, do you want to try that one?

Couch: Sure. I mean, I know that there are certain places in the country that are sort of beginning to rethink things like sex offender registry and housing. A story just came out yesterday about Connecticut, I think, has a task force specifically devoted to that? So I mean, there are some options there, and unfortunately I am in no way prepared to give any sort of prescriptive answer or say this is right or this is wrong. But at least some people are beginning to look into it. And I think that even that is somewhat of a step for figuring out the best way to deal with this segment of the population.

Zuckerman: Ron? Or Kate.

Arkin: Yeah, sure. As I mentioned, I’m primarily concerned with the victims as opposed to the offenders in this particular case. But if you take the methadone example, if we could use it as a management tool where other human adjunct therapies could be put in place to do exactly what you say, that might be appropriate. I don’t believe that this is a cure-all or panacea for reintegrating sex offenders into society. That’s a very complex problem and it also deals with the stigma that you folks were referring to, as well. But I do believe it can play a positi— This is a hypothesis again. I believe the hypothesis that it can play a positive role needs to be understood, and at least in the management of the…if it is a disease, the disease.

Couch: And—sorry I just wanted to jump right back in. As far as integration, whether that’s a good idea, the best methods of doing that, etc., etc., we really can’t talk about that until we know more about this segment. So that seems to me to be a question that is several steps away. The data is scarce. So that’s an important thing.

Darling: And I’m also concerned because the people who are being visited have already been convicted of a sex crime, and that’s actually a very small percentage of the entire population of potential sex offenders or people who have these urges. And right now we do have the problem that these people have a lot of trouble coming forward and even confiding in anyone at all, because all confidentiality is waived in their case because of the reporting requirements. So, while I love the idea that groups are forming to help these people, it’s not enough. We need legal changes, and I think if we can help with technology as well, that’s not a bad thing.

Zuckerman: Can we go to Willow for our next question?

Willow Brugh: Hi. My name is Willow Brugh. I’m an affiliate at the Center for Civic Media, among other things. One of my questions has to do with…you’re doing a lot of a lack of data and a lack of research and other things, and this is also the most academic panel that we’ve had so far. And so I’m wondering if by opening up sex research to a more citizen science approach in the way that the previous panels have had, these outlier cases that you’re speaking of where we’re also lacking data, we might catch more that way, and are there any efforts to democratize sex research in the same way that these other fields have?

Zuckerman: Ron, maybe do you…?

Arkin:

Yeah. Well, I am an academic so I’ll take partial credit for that. I believe that this needs to be studied in whichever way and whatever way possible. Citizen science is fine as long as it is done in a scientific—a manner where we can get a deeper understanding of the problems. You could do crowdsourcing I guess as well, or other strategies to be able to try and engage a broader community. But this does need strictly controlled scientific evaluation, with IRB boards and all these other things, at least in my mind, to get reliable data. As we said, we couldn’t even get accurate recidivism rates, and how hard could that possibly be? From 10 to 45 to 50%, the numbers were all over the place. And that’s extremely frustrating. Because of the dearth of data that you were referring to. [motioning toward Christina Couch]

So, I applaud anyone who is trying to move forward, in any venue possible, in any country possible, an understanding of this particular issue proactively. And not just for the pedophiles. Like I said, I’m concerned also for broader segments of our society, and other societies, that will be affected by the technology that is coming down the pike. We need to understand that. That might be easier to do than the the sexual deviant (as so-called) research, which some may view all of this as sexual deviance if you’re engaging with machines, for example.

Couch: Oh, it’s worth mentioning that virtual reality is also being used to study and treat people who are victims of sexual trauma, as well. So this is not a one-way street. I know that the University California, for example, is putting together—they are trying to build… (I’m going to butcher this.) They’re trying to build a virtual reality simulation to treat PTSD suffered by victims of sexual assault. And so when we talk about amplifying research methods, it’s not just for offenders. Those types of applications can also in some cases be used to actually help victims as well.

Zuckerman: So I want to make sure that everyone who’s standing up gets a chance to ask a question. And so due to time constraints, what I’m going to do is just take the next three questions. We’re going to do our best to answer them to the best that we can. So we’ll go middle, side of the room, and then we’ll end with Viktoria.

Audience 3: So, you all seem to agree that a lack of funding and too much stigma prevents good science on this? I guess my question is let’s say there was no stigma and there was a surplus of funding. What would the science look like? So you suggested strictly scientific controlled experiments. But this doesn’t seem to get at the sorts of questions that Ethan sort of alluded to at the very beginning of how the culture changes in the medium and very long term, and the maybe acceptance or lack of acceptance and how these things normalize, and how it changes the future of these sorts paraphilias.

Zuckerman: Great. So the question there is both what would a concrete research agenda look like, and how would we make a move around this normative question of treating paraphilias as disease rather than as moral failing? Let’s go over here.

Audience 4: So I think there’s some research that indicates that pornography has changed expectations of sex. And so if and when these child sex robots are rolled out—and you say it’s happening sooner than we think it is—who gets to decide whether you can have child sex robot as therapy, and who gets to decide whether you have it as entertainment? And so how will this be regulated?

Zuckerman: Right. Terrific. So questions about the long-term effects of pornography on sexuality. And if this is a therapeutic technology, what’s the line between therapeutic and entertainment technologies. Viktoria.

Viktoria Modesta: Hi. I’m Viktoria Modesta. I’m one of the Director’s Fellows here. I’m very very interested in the whole concept of sexual identity, especially in areas where it’s kind of considered slightly inappropriate, like for example disability and sexuality. It’s just something you don’t really think about. I’m very neutral on this, but just looking at the idea of sexual deviance and how much how much correlation or research has been done to determine whether something like pedophilia is extremely different from all the other different sexual deviances we have in society? You know, BDSM, and obviously up until recently even being attracted to the opposite sex, or bestiality, or all of those range of things that are considered “unnatural,” how much link has there been made between those?

And just lastly, if we are looking at potentially changing unwanted behavior that humans are kind of expressing, is it possible to cross-examine something like violence and the effects of virtual reality or games that have the effect on people with extreme violence? You know, is it possibly connected to just look at you know, is it really possible to cure someone? Is it a disease or is it just a very unfortunate natural deviance that unfortunately doesn’t fit with a modern society?

Zuckerman: So, some rather deep questions there about what the very nature of paraphilias are. Whether there’s a continuum from more socially acceptable behavior like BDSM into more violent sexuality. Questions about in a world where we had the money and the ability to have a research agenda around this, what is it that we would actually work on? How would we work on this question of disease versus moral failing, if in fact this turns out to be a disease rather than just a trait? A very provocative question about what we believe pornography does to desire. And whether robots that might be usable for therapeutic purposes. Kate, can I ask you maybe to take on the pornography question first?

Darling: Sure. I mean, a lot of the research on pornography is very difficult to evaluate. But the fact is that people have been doing research and have been trying to get at the question of how pornography, or violent video games for that matter, influence people’s behavior. And I think that a lot of this is research that, while we need to be critical of it, we can also draw on for these purposes. So I’m basically—I’m answering all three questions at once, I guess. But the methodologies that have been used in in those cases we can also apply to looking at robotics, and VR, which are more physical. I do think that we can’t completely just compare and learn from those findings in those areas, because what we’re talking about is something that’s much more physical, and were very physical creatures. And so that might actually bring it to a new level and have different effects than something that’s just on a screen like pornography or a video game. But drawing on that body of research is definitely the direction in which this would go as a research agenda.

Zuckerman: Christina, could I get you to weigh in on any of those question?

Couch: Sure. The question regarding using technology to treat this type of issue? I think that you [gesturing toward audience] had asked what the research is in terms of pedophilia versus bestiality or other forms of paraphilia. And, I don’t know, to be honest. I’m not a sexuality researcher. I’m not equipped to comment on that specific thing.

But as far as when we look at technology, one thing that has emerged in the twenty-plus years that we’ve been looking into study virtual reality is that it can influence behavior. There’s about twenty years worth of research on using virtual reality to treat post-traumatic stress disorder. For a certain segment of people that have that, using virtual reality can actually reduce the symptoms of PTSD quicker than traditional therapies do.

Virtual reality has also—there’s at least one study that shows that virtual reality can be used to reduce unconscious racial bias. I did a big project last year on racial bias, and unconscious racial bias is an incredibly difficult thing to break, even temporarily.

So, the research seems to be there in terms of can something like virtual reality be used to change behavior. Or at least to influence how we think about behavior. So I don’t think it’s tremendously crazy to think that under certain contexts that maybe you could use this type of technology to actually change behavior within pedophiles. It’s certainly a thing that is worth looking into.

Zuckerman: Ron, I’m wondering if I can get you, specifically, because you made this assertion which I think is very interesting that this is coming whether we like it or not, to wrestle with this question of robots for therapy, robots for pleasure. If we do start exploring the possibility of what we might call the methadone theory, do we end up normalizing sexuality with child robots? Where does that push us? Where does that take us?

Arkin: Okay. Let me first answer two of the questions. I apologize to the third questioner, because I’m not sure I’m capable of talking about the fundamental differences with pedophilia and others.

Regarding scientific methodologies, the human research interaction community has almost become obsessed with data gathering and data collection, to the point where some people think they’ve gone a little too far and not accepting publication to do not have extremely detailed, valid scientific methods to be able to look at and tease out small pieces of interactions which eventually go to both short-term studies and long-term studies. Longitudinal studies as they’re referred to. So I’m confident methodologies could be done which would not happen all at once, you know. There’s a series of progression of scientific experiments by a larger community which would need to be undertaken to get that kind of data.

In regard to the second question, who would tell, who would get those systems? To my mind, it should be physicians and/or courts that would say that this individual is a threat to society, or has been shown to be a threat to society, and as such this is an appropriate treatment for that particular individual, whether to bring them back or to protect society as a whole. My concern, though, is very much related to that. I don’t like hearing about these being used for entertainment. And the one side-effect of moving forward with the design of these robots is the potential black market which could be created for their use by individuals. That worries me significantly, and thus they would have to be a quasi-controlled substance, in a sense, to be able to do this accurately. But even then it doesn’t always work.

The issue of normalization, as you brought up. How does that change of society as a whole, and the acceptance of certain kinds of behavior? As you mentioned, that happens routinely in almost every, even non-technological aspects, as we’ve seen. We’ve seen a change with respect to the definitions of marriage. You notice I put up there robot marriage is a possibility as well. Are you allowed eventually to marry an artifact? The question of bestiality was brought up as well. Is this criminalized because it’s bestiality? I have spent my entire career studying animal behavior, including humans, in a variety of different circumstances. And the notion of studying sexual deviance and actual normal humans interacting with these things can provide the basis for a deeper understanding of how that operates, and then working in conjunction in a truly interdisciplinary effort with sociologists and anthropologists and the like as well, to get a deeper understanding of the potential societal effects is the only effective way to be able to come to answers to that.

Zuckerman: So, thank you so much. I really want to give an extra special thanks to my panelists. This is not an easy panel for anyone to come up and have this conversation for an hour or so. Really appreciate the quality of the questions, the quality of attention from the crowd, in particular the contributions from the folks here on stage.

Let me just check very quickly… Great, I’m still employed by MIT. Okay. Just needed to check in on that very very quickly.