Nigel Warburton: Good evening, everybody. I’m Nigel Warburton, and I’m delighted to welcome you to this event, London Thinks, at Conway Hall, which is the home of the Conway Hall Ethical Society, who are presenting this lecture. And they’re doing that along with Effective Altruism, Giving What We Can, and it’s all in aid of the Against Malaria Foundation. And amazing they’ve raised more than £3,000 through this even already.

I should also mention, if you haven’t noticed already, that Newham Bookshop will be selling copies of Peter’s books and some of mine, even, outside in the foyer afterwards and Peter’s very happy to sign books, as I am. And again amazingly, Newham Bookshop have offered to donate money from the sales to the foundation Against Malaria. So this is unusual. You don’t often go to a philosophy talk where just by showing up you do some good.

But before you get too smug, just remember that if you paid for it and hadn’t shown up, there was quite a queue of people outside who would quite happily have paid a second time. So if you’re an effective altruist, you probably shouldn’t be in the room now. You should’ve sold your seat.

Now, before we begin properly, I’ve just got to tell you where the fire doors are in case you haven’t noticed. There are three. There’s one behind you, one to my right, and one here, clearly marked “Exit.” In the unlikely event of a fire, try and leave slowly and in an orderly fashion, and obviously go out through one of the designated fire exits. But appropriately, you’re being asked to congregate, in that event, by the bronze bust of Bertrand Russell, which is in Red Lion Square. And if you’re not sure what Bertrand Russell looks like, think of a kind of wizened, genial elf.

So the format for this evening is fairly straightforward. After my introduction, Peter’s going to deliver a lecture on effective altruism. We’ll have a short interchange there, two or three questions. And then we’ll open it up for discussion. There are two mics that will rove both upper and lower tiers, and you’ll be invited to ask questions. I’ll say this now and I’ll say it at the end of the lecture as well: it would be very good if your questions are in the form of questions rather than short statements from the floor. That’s going to produce the best effect for everybody here, I think. And obviously there are a lot of people here, so we want to give as many people as possible a chance to ask Peter about effective altruism.

[I’d] just also like to say you can support Conway Hall Ethical Society events, programs, and lectures by becoming a member, and there should be forms on your seats. Or if you can’t find those, there’s a web site where you can join.

So I was delighted to be able to introduce Peter Singer, who’s one of my heroes. He’s a brilliant writer, a brilliant philosopher. I don’t always agree with him. I’m not sure everybody in the room will agree with him. But I don’t think you can deny that he makes you think, and I’m sure that he’s going to give a profound and interesting lecture tonight. Please save your questions till the end. I know it may be difficult for some people to do that, but it’s very important that he gets a chance to put forward clearly his account of effective altruism.

If you haven’t encountered effective altruism before, my take on it is that it’s “bang for bucks altruism.” The idea is that you get the best effect from every penny that you spend, even moment that you spend doing something good for other people. But I’ll leave it to Peter, who is the expert, and thank you very much.

Peter Singer: Thanks very much, Nigel, for that introduction. Thank you all for coming, and thank you all for contributing already, as Nigel said, to doing good in the world.

So what I’m going to do now is to give you a kind of quick run-through of The Most Good You Can Do, which is the title of a new book that I’ve written and relates to effective altruism.

The first question that you might have if you’re not familiar with this idea already is what is effective altruism? And now we can go to Wikipedia. Effective altruism is a relatively new movement, so you couldn’t have done this five years ago, maybe not even three years ago. But now you can, and it will tell you that this is what it is:

Effective altruism is a philosophy and social movement that applies evidence and reason to determine the most effective ways to improve the world.

“Effective altruism,” Wikipedia, (accessed April 6, 2015).

When it says it’s a philosophy, I take that in the broad sense. People sometimes talk about, what’s your philosophy of life? What’s your way of thinking about how you want to live? It’s a philosophy in that sense, rather than a kind of formal system that’s been worked out by any particular philosopher. It’s also a social movement, an emerging social movement, one which has organizations involved with it. There’s no single overarching organizations, but there are a lot of different organizations, and there are effective altruist groups in London and elsewhere. So if you want to connect with that, it’s available.

And that’s one of the things that makes it exciting to be talking about this at this particular time, when there is I feel something new going on among people who want to think again about how they want to do live their lives, what they want to do with their lives. It’s particularly a movement of people of the Millennial Generation. That is, people who’ve come of age since the year 2000. But not only. There are also a number of people of more like my age who are feeling that it helps them to connect with values that perhaps they held sometime before, and values that maybe slipped away during the pursuit of their career or raising a family but that they still want to come back to.

And as you see it talks about using reason and evidence. Nigel was absolutely right in saying it’s about getting the most bang for your buck, but a question then is raised is, so how do you get the most bang for your buck? Well, you need evidence and reasoning to think about that. You also need to think about the values, because just to talk about the most bang maybe is okay. I think that expression comes from military ideas of building weapons, the cost-effectiveness of weapons. Well, you can talk about the biggest bang if you’re building bombs, I suppose. But what we’re talking about is, as this suggests, doing the most to improve the world, and people might have different ideas about what will do most to improve the world, so that’s something that we clearly need to talk about.

Here are some of these values, not taken from something I wrote but taken from someone called Holden Karnofsky, who’s played a role in the movement that I’ll tell you about as I move on.

What counts as improving the world?

Some characteristic EA values

- Take a universal perspective.

- Well-being matters, so suffering & premature death are bad.

- Animal suffering counts. (How much?)

- Other principles (justice, equality, fairness) and morals rules matter in so far as they lead to better consequences – EAs differ on whether they matter intrinsically.

- We should seek to maximize expected value (possibly, subject to moral rules that are absolute side-constraints).

cf. Holden Karnofsky, “Deep value judgments and worldview characteristics”

Just to run through this briefly, what he’s saying is characteristic values. So as I said, there’s no single EA party, there’s no party membership card or creed you have to subscribe to. So these values are only characteristic and you could certainly say, “Well, I’m an EA but I don’t subscribe to all of those values,” but probably most EAs would in some way or other.

So firstly, they really are talking about improving the world. They’re not talking about just improving your local community, however you might define local in that way, whether it’s some part of London, the whole of London, whether it’s Britain, whether it’s Europe. They’re saying, “Look, we really should be thinking about doing good impartially, doing good wherever we can do the most good, whether that’s near at home or further away.”

Secondly, in terms of saying what does good, the general idea is that we want to improve the well-being of beings in the world who have a well-being. And that will mean both human and non-human animals. And we improve their well-being by, if they’re suffering reducing their suffering. We improve their well-being by reducing premature death, at least there would be some discussion as to whether that applies to all beings equally in some way. Does it apply to animals or not? But anyway, certainly if we’re focusing on humans I think effective altruists would say, “If a child dies before its fifth birthday from avoidable poverty-related causes, lets say, that’s a bad thing.” And that does happen in the world currently, according to UNICEF. A little over six million children die every year before their fifth birthday. So effective altruists would say well, that’s not a good thing. If we can reduce that toll, we should do so.

As I said, animal suffering counts. “How much” with a question mark is to say that’s something on which there isn’t particularly agreement. Some effective altruists will focus entirely on issues to do with humans. Others will focus entirely on issues to do with reducing the suffering of animals. A lot will do both. So that’s not anything on which there’s any particularly accepted position.

And effective altruists will, as most of us do, care about things like justice and fairness and equality. But they’ll divide on whether those things are good because they lead to societies with less suffering and with a higher level of welfare, or whether they’re good in themselves even if they don’t improve welfare. So you could say some of them would take an instrumental view of fairness, equality, and justice, and perhaps other moral ideals like that. Others would say, “No, these are intrinsically important, and we ought to try to pursue them even if there is a trade-off, even if you get more equality you get somewhat less overall well-being.” That’s again something on which there’s no settled position.

And Karnofsky says what we should seek to do is to maximize expected value. The concept of expected value here is the value that you will produce if you’re successful, discounted by the odds against you being successful. So some of the things that we might be doing— As you’ve heard you’ve already raised money for the Against Malaria Foundation, so it’s highly probable that money will lead to bed nets being distributed in areas where malaria is a killer, and therefore to lives being saved. But people often talk about other more speculative kinds of things. For example, you might want to work for an advocacy group that will reduce agricultural subsidies in the European Union and in the United States, which would benefit millions of small peasant farmers who want to sell their agricultural products in world markets but can’t get good prices for those products at the moment because these wealthy nations are subsidizing their agricultural producers.

Now, if you wanted to start a lobby group to change that, the odds against you being successful, unfortunately, are quite long. But on the other hand, if you were successful, you would benefit tens of millions of people. So expected value would take both of those things into account. The number of people you would benefit, discounted by the odds against success.

So although I’m typically going to talk about things that have very high probabilities of achieving the good that you want to achieve, effective altruism doesn’t exclude those more speculative ways to change the world, it just says you need to look at the evidence that you really do have high expected value, that you really do have some significant chance of success, even if quite a small one, and comparison to the value you’re going to achieve.

And I’ve added here “possibly subject to morals rules that are absolute side-constraints” because although generally speaking this looks pretty utilitarian, especially if you don’t think that justice, equality, and fairness matter intrinsically but only instrumentally, I don’t want to give the impression that effective altruism is only for utilitarians. I do think, though, that the converse holds. I think if you are a utilitarian, it follows pretty straightforwardly that you ought to be an effective altruist. You ought to be wanting to do these things.

But you could say, “I’m not a utilitarian, I think that there are some absolute rules. I think, for example, you should never torture someone.” Well, is that going to stop you being an effective altruist? Pretty unlikely that you’re ever going to actually be in a position where you would maximize welfare overall, minimize suffering overall, by torturing someone. Not completely inconceivable, but extremely unlikely.

So I think you can safely say, “Even though I’m not a consequentalist because I think some rules are absolute, there are some things that you must never do, that leaves a large area in which I can be an effective altruist.” And while that’s a pretty extreme example, generally speaking, any ethic will leave some room for doing good. That is, there might be ethics which have all sorts of rules that you have to follow that limit your scope for acting in many situations, but generally speaking they would say, “…and if you can do good to people, particularly if you can do good to people at minor cost to yourself, then that’s what you ought to do.” And if you hold an ethic that is like one of those, then there’s plenty of scope to be an effective altruist and to do good.

Okay, if you ask is there a philosophical basis for these sorts of positions, I think there are various philosophical bases and I’m not going to take the time to go into them all. But I do want to just show you one of my favorite philosophers, who was a utilitarian. Henry Sidgwick was the last of the great 19th century utilitarians, and the least well-known. If you’re not a student of philosophy, you’ve probably never heard of him. Maybe if you are a student of philosophy, you’ve still not heard of him. But you will have heard of Jeremy Bentham, you will have heard of John Stewart Mill, and Sidgwick as I say is the third of that trio of great utilitarians. And in my judgement he’s far and away the best philosopher of the three, although he’s definitely not the best writer of the three. And that’s probably why The Methods of Ethics, which is a large book, runs to just over 500 pages, is not as widely read as, for example, John Stewart Mill’s short essay, “Utilitarianism.”

On Taking a Universal Perspective

…the good of any one individual is of no more importance, from the point of view (if I may say so) of the Universe, than the good of any other; unless, that is, there are special grounds for believing the more good is likely to be realised in the one case than in the other.

Henry Sidgwick, The Methods of Ethics, 7th Edition (1907) p.382

But what Sidgwick is saying here is something that he thinks of as a kind of self-evident truth, that rational beings can see that from the point of view of the universe… Note the “if I may say so.” Sidgwick doesn’t really think that the universe has a point of view, but he says we can imagine taking that point of view. And from that point of view, my own well-being is no more important than yours, or yours, or that of somebody far away around the other side of the world, if the quantities of well-being that can be achieved are just the same in all of us.

So that’s the kind of basis for the universal perspective, or could be the kind of basis for the universal perspective of effective altruism, and the idea that just as I would wish to reduce my own suffering if were suffering and would want somebody else to help me if they could do so, especially if they could do so at low cost to themselves, so we ought to recognize that the suffering of others matters as our own does, and we ought to help them if we can do so at low cost to ourselves.

So that’s a little bit about the values of the movement. I now want to tell you a little bit about some of the people involved in it and some of the things that thinking about effective altruism has led them to do.

Here’s somebody who was instrumental in getting the movement going just a little less than ten years ago. Toby Ord was at the time a graduate student in philosophy at Oxford, and he was living on a graduate studentship, which I think at the time was around £14,000 a year. And he felt that actually that was an adequate amount of money to live on. Felt he [] didn’t really lack anything that he needed, wasn’t suffering too much. But he realized of course that if he was successful, if he got his PhD and went on to an academic career, he would soon be earning more than that and perhaps eventually be earning significantly more than that. And he wondered what would he be able to do if he continued to live on something not too far above his graduate studentship, adjusted for inflation, and therefore had the rest of his earnings to spend on something that would do good in the world. What would he be able to achieve with those savings?

So he did the calculations. He looked at a typical academic career trajectory and the kinds of salaries that you might get, deducted something like the graduate studentship from each year. That left, of course, a quite substantial sum over, if he imagined himself earning that amount of money into his sixties. And then he thought, okay so here’s the sum of money, now what’s a good, cost-effective thing that I could do with it?

And what he hit up on after looking at some studies was activities that help people to see. Either restore sight in people who’ve become blind or prevent them becoming blind through a preventable cause of blindness, which the largest preventable cause of blindness in the world is a condition called trachoma.

Trachoma is quite easy and inexpensive to treat, and at least one form of blindness is very easy to fix, and that’s blindness from cataracts. I’d be really surprised if there’s anybody in the United Kingdom who’s blind because of cataracts. If they are they must be very isolated from the National Health Service, because if you’re starting to lose your sight from cataracts in Britain to the point where you’re becoming disabled, your doctor will refer you to have them removed at no cost to you. It’s a very simple procedure.

But if you’re unfortunate enough to be living in a developing country and you are yourself poor, then you’re not going to be able to get your cataracts removed. You can’t afford it and nobody else is going to pay for it for you unless there is a charity that is providing that. And there are charities that do that, and a lot of this, you could debate the cost of how much that is. You could say probably around something in the region of maybe £50, maybe £100 to restore sight in somebody who has a cataract.

So Toby did the sums with those sorts of figures and he came up with the conclusion that he could prevent blindness in eighty thousand people if he just continued to live on something like his studentship. And he thought that that was a pretty impressive thing to do. You imagine a big football stadium. Imagine Wembley full of people and you could restore sight in all of them, and that would be an amazing life’s achievement, and you don’t even have to be Bill Gates or anybody really wealthy to do that.

So Toby was somewhat surprised with what he had learned about the power of one person to make a big difference to the world. And he thought other people ought to know about that. So he started an organization called Giving What We Can, which has subsequently flourished and has chapters in various places and outside Britain as well, and also has a web site that you can look at which will give you guidance about which charities are highly effective.

So that’s one thing that you can do that effective altruists do, and that is reduce their expenditure. Maybe not right down to the level of what Toby’s doing, but reduce it in some way and do a significant amount of good with what you’ve then saved.

Here’s another former Oxford grad student, Will MacAskill, who helped Toby to found The Life You Can Save, but also got interested in the question of career choice. He thought that people spend a lot of time in their career. In fact Will also did some sums and coincidentally he also came out with an answer of 80,000. That’s the number of hours that a typical person will spend working in their career. So he set up an organization or web site called 80,000 Hours, and you can see it here. This provides advice on an ethical choice of career, on thinking about how can I through my career make the biggest difference for good in the world?

It’s not that there wasn’t any ethical about careers before. There was, but Will though it wasn’t really offering all the options. Typically it would say well you could work for a non-profit organization, choose a good one and then if you work for it you’ll be doing good. Or maybe you could go to medical school and then you can then yourself perform the surgeries to remove eye operations. Those kinds of things, which are certainly good things to do.

But Will thought that at least for some people, not for everybody but for people with the right skills and the right character, there might be a better option which most people would probably not think of. And here’s somebody. Take one of my former students at Princeton, who took this option.

Matt Wage could’ve had also gone on to a graduate course in philosophy like Will and Toby. He was in fact accepted by Oxford to do graduate work there. But after talking to various people in the effective altruism movement, he thought that he could do more good by taking a position in which he would earn more and then donate a large portion of that to effective charities. Now you might say, well how do you know that you’re going to do more good that way than by working for the NGO? The way Will and Matt think about this is as follows.

Suppose that you see a job advertised by an aid organization that you think is a good one. Let’s just say it’s Oxfam, to take a well-known one. So suppose that you apply for that job and you’re successful. You get the job. And then you work for many years for Oxfam doing the best that you can do for it. How much good have you actually achieved by your decision to work for Oxfam? At first answer you might say well, everything that you did in that position, that’s how much you’ve achieved. So you’ve had a lifetime doing good.

But if you had not applied for that job, somebody else would’ve got it. Oxfam is a well-known, popular organization, so people would apply for it. Probably other good people would apply for it. Since you got the job, let’s say you were the best person in the field. But the amount of good that came from your deciding to take that job is not all the good that you do, but it’s all the good that you do minus all the good that the next best applicant in the field would’ve done. And you’ll never really know, but that might be quite a narrow difference depending on how strong the field is, obviously.

Now, compare that with what Matt is doing. What we’re interested in is not how much good Matt does for the firm that he works for. It’s true that the next-best applicant would’ve done probably almost as much good for the firm as he would’ve. But if you’re an effective altruist you don’t really care about that. What you care about is the fact that Matt, a year after graduating, was able to donate $100,000 to an effective charity, and the the next year and the next year. He’s about three or four years out from graduation now, so we don’t know how many years this will continue, but so far it’s going well.

Whereas, had Matt not applied for that job with the trading firm in 1 Wall Street, it’s not the case that the second-best applicant would also have given $100,000 or even $95,000 to effective charities. It’s extremely, extremely unlikely that that would’ve happened because very few people who get jobs on Wall Street do give a very large proportion of their salary to effective charities.

So in that sense, all of the good that Matt’s donations do is good that is directly attributable to his choice to work on Wall Street, because that money for example could set up an entirely new position for Oxfam or for some other organization. And that could therefore do all of the good that that person in that new position could do.

Moreover it’s also more flexible. Matt might start out giving to Oxfam because that has a good reputation. Then he might get some more information, some more data, and said, “Oh, actually I think the Against Malaria Foundation probably gives me better value for my money, so I can switch my donation,” and you can do that very easily. Not necessarily going to be the case that the Against Malaria Foundation has a vacancy just when you reach that decision that you say okay I’ll leave Oxfam and go and work for them. They may say, “Sorry, we don’t have any free positions at the moment.” So it’s more flexible in terms of where you’re directing your— You can be more responsive to the best information available, the best evidence, and that’s what effective altruists are interested in. Getting evidence for where you can make the biggest difference.

And just one more person I wanted to mention, Julia Wise, somebody who even when she was on a small salary was giving a substantial amount to effective charities. But I wanted to mention Julia particularly because she writes quite an engaging blog, givinggladly.com. And if you want some information about an effective altruist (who is not a philosopher this time, by the way) and how she reached her decisions and how she feels about what she’s doing, do have a look at givinggladly.com

The next question that effective altruists might ask is, “How do I decide what cause I should give to?” So far I’ve been talking about global poverty, and I said a little bit about animal suffering, but of course they’re not the only causes that people give charitably to. There’s an important issue about comparing and deciding between causes, and I think that’s done quite poorly at the moment in the philanthropy field. So another, I hope, benefit of the emerging effective altruist movement is that it has the potential to transform philanthropy. Philanthropy is a pretty large industry. Private philanthropy is quite significant in terms of the amounts of money that are raised. I don’t actually have the figure for the UK in my head, but for the United States I think it was around $300 billion, about 2% of Gross Domestic Product. So quite substantial. And if it’s not being used effectively but it can it can be made to be used more effectively, there’s an enormous potential to do more good there.

Unfortunately at the moment I think typically philanthropy is not being used very effectively, and that’s partly because of the kind of non-judgmental attitude that philanthropy advisors and people generally have about philanthropy.

So I’ve picked as an example of this one of the biggest philanthropy advisors, the United States-based Rockefeller Philanthropy Advisors, a spin-off of the Rockefeller family’s own philanthropy. They have a web site, which these slides are taken from about offering advice on philanthropy, “your philanthropy roadmap,” and I certainly agree with the statement (you probably can’t read it there under the heading) which says, “Giving away money is simple. Giving away money effectively is an entirely different matter.”

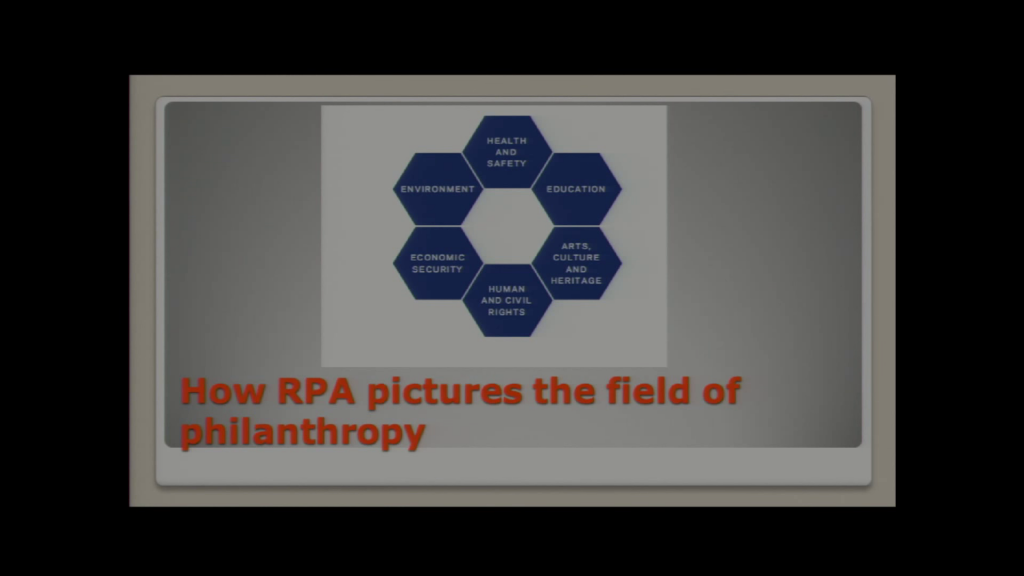

That’s a promising start, to recognize that. But after that it goes downhill, unfortunately. This is a little leaflet called Finding Your Focus in Philanthropy that you can also download off the web site. And it’s sort of asking this question, what are you going to focus on? You want do to some good in the world? You want to be a philanthropist? Are you interested in that? What are you going to focus on?

Well, this is a little chart that’s there, and it’s significant. Even though you might say, “Well it’s just dividing up the field into various categories,” the way you divide things up of course reflects a lot about the way you think. Here’s a division of the field of philanthropy which says nothing about, are you going to give in your own country, let’s say in the United States or United Kingdom, in a wealthy society, or are you going to give in a developing country? And that’s probably the most critical—if you’re trying to help humans, anyway—that’s the most critical decision that you can make. Much more critical than decisions about are you going to do stuff in the health field or in the education field or in the economic security field, or even in the human and civil rights field. Because I would argue that the difference in the amount of good you could do by helping people who are in developing countries is greater than the difference between those choices of fields.

If like me you’re interested in questions of animal welfare and animal suffering, it’s also curious that that just doesn’t even appear on this chart. It just doesn’t fit into any of those particular little boxes.

But what is the most urgent issue? There’s obviously no objective answer to that question.

Rockfeller Philanthropy Advisors, Finding Your Focus in Philanthropy, p.3

But that’s a sort of by-the-way point. The point that I really wanted to focus on is this statement, which is unfortunately pretty characteristic of philanthropy advice. It’s basically saying, so you want to say which of all these causes is the most urgent or the most important? And Rockfeller says, “There’s obviously no objective answer to that question.” So there’s a kind of relativism between causes. That’s convenient for philanthropy advisors who don’t want to say to anyone who comes in with a particular fixed idea that that’s not as good as some other thing that you might do. You might go and find a different advisor if [they] say that.

But nevertheless I think this presents an unfortunate image that somehow all causes are alike. And that seems to me to be clearly not true, and you can find evidence that it’s not true even from the examples that this particular leaflet puts forward.

So here are two examples that are mentioned.

RPA offers, among several examples:

1. Ted Turner’s 1998 $1bil to UN to scale up proven health programs against killer diseases that largely kill children in developing countries.

Cost per life saved may be as low as $80.

[presentation slide]

One was a really pioneering donation that Ted Turner made in 1998 to scale up United Nations programs to deal with killer diseases, diseases that killed children in developing countries, diseases that we know how to cure or prevent. We know how to prevent measles by immunizing kids, for example. We know ways to reduce the incidence of diarrhea, which is a major killer: provide safe drinking water, provide oral rehydration therapy in decentralized ways so that kids have access to it if they are in danger. We know, as we’ve already heard, that by distributing bed nets you can prevent malaria.

So Ted Turner helped to scale up these programs, and subsequently they were supported by others including Bill Gates. But at least when its tarted, it was estimated the cost per life saved was as low as $80. That’s not to say that it’s still as low, because obviously you deal with the areas where you can most cheaply save lives first. You pick the low-hanging fruit. We’ve made a lot of progress. There are significantly fewer children dying before their fifth birthday now than there were in 1998. Would be fewer than half in that time, even though the world’s population has risen. So we’ve made a lot of progress. We have fewer premature deaths. And that was I think a very effective form of philanthropy.

2. Lucile Packard’s 1986 gift of $40 million + ongoing support to establish a children’s hospital in Palo Alto.

In 2007 the hospital spend $1–2 million to separate a pair of conjoined twins from Costa Rica; further support came from the charity Mending Kids International

[presentation slide]

But Rockfeller Philanthropy Advisors puts is more or less on the same page without comment with this donation from Lucile Packard to set up a children’s hospital in Palo Alto. If you don’t know where Palo Alto is, it’s at the Southern end of Silicon Valley, California where Stanford University is. It’s the third wealthiest community in the United States. So there aren’t children dying from diarrhea or measles or malaria in Palo Alto. And if you’re going to save the lives of children you’re going to do it with very expensive high-tech medicine because other needs are already being covered. Or perhaps you’re going to perform heroic surgery to separate conjoined twins, as in the example here, which is going to cost you between one and two million dollars for the separation of a pair of twins.

So I think if you’re going to say there’s no objective choice, are you really saying you can’t choose objectively between saving a life for $80 and separating a pair of twins for more than a million dollars? I don’t think it’s very difficult to say there is an objective answer to which of those ways of using your money is the better one.

And here’s a different kind of example. This is something that was just in the news a month or two back. Some of you may have been to New York, some of you may know what the Lincoln Center is. It’s a center for classical music and opera. It has up to know had, I thought, a perfectly decent concert hall known as Avery Fisher Hall. But the Lincoln Center decided that hall needed renovation, and it called for donations. It said, incidentally, that the cost of renovating it would be not $100 million dollars but $500 million dollars, but it got a sort of lead-off donation from David Geffen of a $100 million. David Geffen is an entertainment mogul who’s behind DreamWorks and others in the entertainment field.

So could David Geffen have done better with his $100 million dollars than help to renovate a concert hall for wealthy Manhattanites and other tourists who go there? Seems to me again quite easy to say that he could have. Perhaps he could’ve saved the sight of a million people, if a $100 is a reasonable estimate for doing that. He could certainly have saved the lives of a large number of people in other ways, for example by promoting the distribution of bed nets. Could save, let’s say, maybe fifty thousand, a hundred thousand lives, depending on our estimates of cost there. But certainly he could’ve saved a substantial number of lives, and it’s hard for me to see that anyone could seriously believe that having an even better concert hall than what’s now going to be of course the David Geffen Concert Hall, could somehow be compared with those other things that you could do with that amount of money.

Singer’s view is that we should minimize suffering… but what about improving all areas of human experience? Playing off one area that needs more money vs another is a false choice. Both arts and treatment of human illnesses are worthy of support

Even, commenting on Nicholas Kristof, “The Trader Who Donates Half His Pay,” New York Times, April 4, 2015.

Some people will say well, why not do both? In fact, when Nicholas Kristoff wrote a column in The New York Times about my new book a couple of months ago. Somebody commented exactly that. Why can’t you do both? Why can’t you support the arts and support helping the global poor? It’s a false choice, he said.

Well, I don’t know where this person banks, but my bank account won’t let me write a check for all of the money in my bank account, give it to the Against Malaria Foundation, and then let me write another check for a museum or art gallery or concert hall again for all of the money in my bank account and give it to that charity, and honor both the checks. So I don’t think you can do both. Of course you could divide it in half. You could give half of that money to both. But I’m sure you can see that if you do that, then there’s going to be a significant number of people who will remain blind who wouldn’t’ve if you’d given it all to that. Or a significant number of children who’d die from malaria who wouldn’t’ve died if you’d given it all to the Against Malaria Foundation. So I think inevitably we have limited resources. There’s a trade-off. And you can’t really do both.

Not wanting to go on too much longer. I do want you to have some time for questions. But let me just say a little bit about assessing effectiveness.

I mentioned at the second or third slide, I had a set of values for effective altruists by a guy called Holden Karnofsky. Holden Karnofsky and Elie Hassenfeld founded this web site, which is called GiveWell, which assesses charities for their effectiveness. And if you look at this pie chart here, it looks a bit alarming. They’ve reviewed a lot of charities and there’s only this thin wedge of their top charities.

So does that mean that most charities don’t do any good? No, it doesn’t mean that. It’s that most charities do not have sufficient evidence to convince GiveWell that they are doing a lot of good. Those are two different things. They may be doing good, but they can’t really prove that they’re doing good. And GiveWell wants you to donate to charities that can produce high quality evidence that they are doing good. So that’s why these charities are not recommended, but a small number are and you can therefore be highly confident that those small number do really have good evidence of what they’re achieving.

Good evidence might, for example, involve randomized controlled trials, the same method that drug companies use to show that a new drug works. So you have some kind of intervention. You want to see whether that works, at what cost. You don’t have the resources to give it to everyone who needs it or to every village that needs it or every community. So you get baseline measurements in all of the communities, then you randomize and you give this treatment in half let’s say, if you have the resources to do it in half of them.

And then you go back and do more measurements, and you see what kind of difference you’ve made. You see whether fewer children have died from malaria. If you have a different kind of intervention, let’s say in education, you see whether more children have completed schooling. That’s the best kind of evidence. You can’t always produce it, but that’s the kind of evidence that GiveWell will look for if available.

They also demand a high level of transparency. [They’ll] want to know what happens to the money that comes in. Where does it go? How do you track it? How do you know you’re doing good?

So there are half a dozen top-rated charities in this top group. And since you’ve already contributed to Against Malaria Foundation, you’ll be pleased to know that that’s among GiveWell’s top-rated charities. So that’s one way of looking at effectiveness. Use the research that other people have done, you don’t have to reinvent the wheel, and draw on that.

GiveWell was, I think, the pioneer in this field, and its work is used by others who may do additional research of their own. This is the organization that, as I mentioned, Toby Ord and Will MacAskill set up, Giving What We Can. If you go to this “Where to Give” tab, you will find information about their recommendations about the best charities as well. And there’s one that I’m involved with. My previous book came out in 2009. It was called The Life You Can Save, and it spawned an organization, people who wanted to do something about this cause and it also has a web site. It also has information about where to donate, which draws on GiveWell’s research but also does slightly loosen the criteria to allow other organizations for which we think there is evidence that they are doing a lot of good although the evidence may not be of the same high quality as GiveWell demands.

So I think I’m going to stop at that point, because I know Nigel’s going to ask me a couple of questions and then we want you to have time for some questions as well.

Thanks very much.

Warburton: Thank you very much. I’d like to just get clear about how radical your approach is. Here are three cases. I’d love to know what you think about them.

The first one is— I’m sure there are people in the room here who contribute to charities that help alleviate poverty in Britain, and there’s some figures which suggest there’s increasing poverty in Britain. We’re seeing food banks being used by many people. The first scenario…if you’re an effective altruist, do you think that people who donate money to food banks and charities that support them like the Trussell Trust are immoral because they know well that there are people who are more needy in other parts of the world? So that’s the first one.

The second one, if you think back to the Chilean miners deep underground. Thirty-three of them trapped in sweltering conditions. It cost millions to get them out. It wasn’t really likely that they would survive. It was almost miraculous that they got out. From the point of view of people deciding what to do, if you’re an effective altruist you’d presumably say, “Write those thirty-three off. That money could save many more than thirty-three people.”

And the last one. Imagine you’re out for a walk in a very expensive pair of vegetarian shoes, and these shoes—

Singer: They’re not so expensive.

Warburton: But say $300 worth of shoes, and you see this child drowning in a pond. [some laughter from audience] Now, if you go into this pond, they’re not waterproof shoes, these ones, and you’re going to ruin the shoes. But you know on eBay, particularly Peter Singer’s shoes, would fetch more than $300. So shouldn’t you just auction your shoes on eBay and let the child drown? Because with that $300 you could save many more than one child.

If you take the point of the universe in each one of those cases, or the global perspective, you’re going to end up with a counterintuitive conclusion, as far as I’m concerned.

Singer: Yes. So sometimes, as you would well know, philosophy does end up with counterintuitive conclusions. But sometimes there may be other things that are to be said about some of these things.

So are you immoral for helping the poor in Britain? I certainly wouldn’t use that term. I might say there could be better things that you could do with your money. Assuming we’re talking about money, right? If we’re talking about volunteering, I think it is important to recognize that volunteering is an important charitable contribution.

It may be that you can actually do more good in your local community than you can abroad. I certainly don’t recommend people thinking, “Oh, I’m gonna go and help some poor people in the developing world over my summer vacations, so I’ll jet over there and spend a few weeks helping them to do something, which probably they already know better how to do than I do, in fact.”

So volunteering often, I think, can be more effective locally, although of course there are ways in which you can volunteer to raise awareness about global poverty, too. So I would say rather, I tend to praise people for making contributions to help others in general, because there isn’t enough of it. But I’ll certainly praise them more highly if they think about doing that as effectively as they possibly can.

So that was the first case. Your third case was about my shoes. I for—

Warburton: The miners.

Singer: The miners. The Chilean miners, right, of course.

So yeah, I mean it’s clearly true that the money you spend on rescuing individuals—that’s one example; there’ve been other examples, too—could save more lives if you didn’t. The question is what would that say about us, what would we feel if we knew that possibly those miners were alive and we weren’t going down to help them? Perhaps if we knew that the money was helping other people, perhaps if we actually followed through with that and we saw, we followed the donations and we saw here they’re helping these people who would otherwise be in danger of dying from one or another causes, or here they’re restoring sight in people, maybe then we could actually understand the impact and we could feel emotionally okay about it.

But if we’re not, if it’s just like well, this is going to come out of some general pot and who knows what will be done with it if we don’t spend it on rescuing the miners, then I think we’re failing to express our concern for others in a way that rescuing people does. But having said that, as I say, I think obviously there do have to be limits. We’re emotionally pulled by identifiable victims, emotionally pulled by the wives or partners who were so anxious of course about their loved ones. And it’s very hard to just say no, this is too expensive. But sometimes we do have to do that.

On the shoe example, they have to be really super-expensive shoes because I think, looking at GiveWell’s research, $300 doesn’t save a life. We have some people from Against Malaria Foundation here tonight, and they could tell us their view, but GiveWell says something more like $3000. It may not be that much, but it’s not as cheap as I myself thought it was many years ago when I used that example that you’re riffing off in terms of that you should be prepared to ruin your expensive shoes to save a life.

But you could of course change the example. Peter Unger had this example that you will be familiar with where the trade-off is your most valuable asset, which is a classic Bugatti that you have invested in and is uninsured and you’ve parked it at the end of a disused railway line. You’ll then walk up the line and you see there’s this runaway train, and the train is going to go through a tunnel where it will kill a person, let’s say a child. And the only thing you can do to save the child is to divert the train down the disused railway line where it will smash through the aging barrier at the end and demolish your Bugatti, which you’ve invested your life’s savings [in].

Now, here you could certainly say— I mean, Unger’s view was even in that case, you ought to save the child. But here you could say well, put your Bugatti on eBay, you’ll definitely get enough to save many lives then. And I think I would say as long as your resolve to sell the Bugatti and use it to donate to the Against Malaria Foundation is not going to weaken and you really are going to do that, then that’s a better thing to do, even though in this case obviously it’s a very hard thing to do because there’s again and identifiable victim in the tunnel and you can’t exactly say who your donation to AMF is going to save.

Warburton: So you’d bite the bullet, basically.

Singer: On that one I would bite the bullet, yes.

Warburton: Another question. Seems to me that you’re asking what’s the most good we could do. This is within a tradition of how we should live, the big philosophical question, “How should I live?” But for most of us who aren’t moral exemplars, the big question isn’t what’s the most good I can do, but how can I live a good enough life? How can I live an adequate life? And it seems that if you start talking about what’s the most good I can do, you end up with a position where you’re aiming so high that you lose sight of many things.

So some of the good we that do at the human level gets sidelined for the sake of the view of the universe or the global view. And I’m concerned that much of what’s good about human interactions stems from compassion, the kinds of things which you talk about as emotions which get in the way of effective altruism. And I’m worried that by focusing on the most good we could possibly do, that we might lose something valuable.

Singer: Well, there are a number of questions there. I think it’s worth putting out there the idea of the most good, because even though very few people are actually going to manage to do the most good they possibly can, it is an ideal that sets a standard, that you can measure yourself against, and I think there are people who’ve gone surprisingly far in doing the most good.

So I think it’s worth saying. Does that mean that if you set out to do that you will be less likely to do a lot of other good? Again, there are trade-offs you have to admit. There are things that you may spend time doing which will take you away from the people that you’re close to and from smaller compassionate acts. That’s always possible.

I think that humans are infinitely varied and they can distribute themselves along a spectrum there. And I think it’s good that some people should be quite far along that spectrum and aiming to go further, and others may just be moved a little bit by this kind of ideal. But again it’s a bit like the example where you said are people immoral if they’re helping domestically. I’m not really going to blame people for not doing more if they’re doing something that is already significantly above what most people in the community do.

I think my objective is really to raise the standard of what we think of as living ethically. And I think we’ve got a very long way to go. We can raise that standard quite a bit without endangering the things that you’re talking about, and we can have another look and readjust if we get further in the direction that I think we should.

Warburton: But donating a work of art to a public art gallery or funding a music hall is going far beyond what most people do in the area of helping other people.

Singer: Yes, that’s true. Well, I mean these tend to be pretty wealthy people who are doing this, but yeah often they are going beyond that. But that’s perhaps something that I think is so clearly in the wrong direction that I think we ought to talk about it. It’s not that if I meet David Geffen in the street I’m going to say to him, “You’re a terrible person for donating this,” but I guess I would say, “Look, you’ve still got various hundreds of millions left, how about thinking about whether you can do more good in some different direction?”

Warburton: Okay. We’d probably do more good by taking questions from the audience. I’ve already spotted one in the back, there. As I said, could we keep these to short questions, because we’ve only got about 25 minutes maximum, 20 minutes maximum here.

Audience 1: Hi. I just want to go back to animals, just [to pass over?] this very interesting discussion we just had. Can I just clarify, are you presenting the view that equal suffering matters equally irrespective of species?

Singer: The answer is yes. I think that equal amounts of suffering matter equally irrespective of species.

Audience 1: So what happens when we turn our TVs on and we see, as we do practically every night, big cats killing okapis? We see animals savaging animals, and we accept this. We accept that there are photographers there. We don’t send in the armies. What’s going on here? Is this wrong?

Singer: Well, there may be other values at stake here. We may think that there’s value in having animals living in their environment, behaving in the way that they have evolved to behave, and that that value in some way outweighs the negative value of the suffering of the okapi in this case. We may also be troubled by the question of what would we be doing here? I mean, I guess we could go in and kill all the predators and then we would have to provide birth control for the prey animals. Do we want to get into that? Is that going to be the most effective way of reducing suffering? I’m skeptical that it would be.

Audience 1: Alright. Okay.

Audience 2: Thank you. Peter, how much do you think that say, education in general, especially from a young age can have any impacts on becoming a more and more efficient altruist in the future?

Singer: Education can have a big impact on that, and I think it’s actually really a good thing that people at high school level now in this country are able to think about these questions, that philosophy is more widely taught in schools than it was and it raises these kinds of questions. But just in general I think making children aware of the kind of world that they live in, of the choices that exist, or the fact that some people are much much less fortunate than they are, I think all of those things are really important and help to prepare people for making life decisions. And I think the more education they get in that, the higher the probability that they’ll make good life decisions.

Audience 3: Hi. I just wanted to ask, you spoke about the comparison between donating to Africa and donating to a Californian hospital, and suggested that you could realistically objectively say that one is a more effective moral thing to do than the other. But you opened by suggesting that effective altruism is broadly normatively neutral in terms of ethics.

Singer: No, I don’t think I said effective altruism is normatively neutral.

Audience 3: Well, neutral in the sense that you don’t have to be a utilitarian.

Singer: I said you don’t have to be a utilitarian, definitely.

Audience 3: So my question is, since on the one hand you’re sort of suggesting that you can choose to prioritize to some degree as you will. You can choose not to prioritize non-human animal suffering if you see fit. If you’re given that degree of flexibility, haven’t you abandoned the notion this sort of objective framework of weighing up suffering, given the degree of non-human suffering in the world?

Singer: I may not have been precise enough or clear enough in what I said. In discussing the slide about characteristic values, I wasn’t saying that in my view whether you were concerned with animal suffering or not was just a matter of anybody’s choice being as good as anyone else’s. I was saying that within the effective altruist movement there are people with different views on that.

My view is as I said in response to the first question that I think animal suffering does count, and the real question is how do you reduce it at what cost per unit of suffering? Can you reduce the suffering of non-human animals? And incidentally, if I was thinking about that I certainly wouldn’t be thinking about predators and prey in a natural environment, I’d be thinking about reducing the number of animals suffering in factory farms, and that seems to me my far the biggest cause.

But I do have views on that. The real question I guess is to say how equal quantities of suffering count equally, as I said, but how much do we think a pig in a factory farm suffers? And how does that compare with the suffering of a child with malaria, for instance, or the parents watching a child with malaria die. Those are quite difficult sorts of comparisons.

So there are some of those comparisons that I don’t really have answers one. But some of them I think are easier, and I think the ones about saving lives in developing countries or in African countries is one of the easier ones.

Audience 4: Thank you very much. Professor Singer, along the lines of the Bugatti example, but something less extreme, [a] more everyday kind of dilemma. You’ve got a choice of going to buy a pair of jeans for £50 in a store where you know that they’ve got the reasonably good kind of policy on supply chain, fair treatment for workers presumably in the third world, possibly organic materials used, whatever. And then you’ve also got the other choice maybe paying £5 in your cheaper store. Would you then buy something for £5 in a store where you know that the supply chain is of a different kind? Workers have not been treated fairly, maybe have been exploited and so on. But you can donate the difference, the £45 to a charity of your choice, effectively. Perhaps more effective than the difference it might make to the workers in the two different working conditions.

Singer: Yes, that is a difficult choice. I think there’s something to be said for supporting good working conditions in general, not just for those workers but with the hope that this will spread and set standards. And the same is true for the fact that it’s organic or sustainable or whatever else that it might be. So I think there’s value in supporting fair trade products, and I certainly wouldn’t discourage anybody from doing that.

In your example there was a very big discrepancy in price, which enabled you to give a substantial amount to charities. And maybe if the difference really was between £50 and £5 for essentially the same product or a product that met your needs as well, maybe you would do more good with donating the £45. But typically if you shopping for fair trade coffee, the difference is going to be what, 10 or 20% or something like that. So in those cases I think it’s good to buy the fair trade product.

Audience 5: Hi, Peter. The question that’s going round in my mind is, doesn’t effective altruism result in us over-prioritizing those things that are easier to measure? A particular example might be that an effective altruist might think it’s better to give £10 to a starving child rather than giving that £10 to a campaigning organization that’s campaigning against structural inequality. But the ultimate outcome of that campaigning work might have a vastly greater impact; we just don’t currently have the tools to effectively measure it.

Singer: Yeah. I think that is a problem with the way that web sites are looking at charities mostly now. And I think I mentioned briefly that GiveWell is extremely rigorous and does require high standards of evidence, and with The Live You Can Save, the organization that I’m involved with, we’ve slightly loosened those standards so that we include organizations that do advocacy work of the sort that you’re talking about, that arguably does pay off. And in the book The Most Good You Can Do, I have an example of one of Oxfam’s campaigns to get Ghana to distribute some of its oil revenue (Ghana discovered off-shore oil not that long ago.) to distribute some of that revenue to some of the poorest farmers in the country to help them to farm better, rather than as has happened in Angola or Ecuatorial Guinea have the revenue just flow to the pockets of the elite. So Oxfam supported civil society organizations in Ghana that were working for this, and that’s an advocacy campaign that paid off extremely well for a small amount of money.

So, I do think you’ve got to somehow try and include that. But to do so you have to computer in some way the odds of success, to get that expected value figure. And it’s extremely difficult, I agree. So I hope that in coming years we’ll get more work being done on that and more people trying to track the success or failures of those campaigns to give you some kind of insight. But with some of them, like the one I mentioned about agricultural subsidies, something like that, it’s very difficult to estimate how likely it is that you’re going to be successful.

Audience 6: Most of the things that have been described are very worthwhile, and I appreciate that. But I just feel a little bit uncomfortable about the idea of giving a charity. I would much rather see things go towards countries and governments being as independent as possible, and doing their own things. So I wonder if there could be more emphasis on education itself, and things like campaign against the arms trade, which has a vested interest in war and so many corrupt governments. That sort of thing, rather than material things necessarily. [some clapping from audience]

Singer: I see you’ve got some support out there. So yes, I think that some of these campaigns can be worthwhile. It’s again one of those things you can start campaign against arms. You know Oxfam were involved in a campaign which led to the passage of a law in the United States to try and make the arms trade at least more transparent, more reportable as to what they were doing so the weapons could be tracked. I don’t really know whether it’s going to achieve a great deal, but it may. These campaigns are quite difficult to achieve, again something as large as the arms trade.

Education I certainly do agree, and if people said, “I think that educating children in developing countries is an effective thing to do,” I wouldn’t disagree with that. I would say you need to find effective ways of doing it, and again you need to do the proper studies to show that what you’re doing is a cost-effective way of doing that. But I certainly thing that that’s a very important thing to do. And I’d add particular educating girls is very important and also has a spin-off in terms of reducing fertility and therefore helping to slow unwanted population growth.

Audience 7: Hi. Thanks for you talk. I recently came across a term that described a problem that I’d encountered, particularly the sphere of trying to reduce suffering through public health measures, which was “temporal discounting.” Which is basically where you ignore your and others’ future suffering in favor of a benefit you receive now. For example with smoking, people might say, “But I love smoking,” but you know that in future there will be a great deal of suffering as a result of that. And I just wondered what you would say to people who object to public health measures on the scale of information up to restrictive laws, who say, “But you’re taking away my freedom of choice.”

Singer: I think effective altruists are universalists, not only in the sense as I said that they don’t differentiate between whether suffering occurs here or in Mozambique, let’s say. But they’re also universalists in the sense that they would not differentiate between suffering that occurs in 2015 or in 2115.

The only discounting that I think is acceptable is discounting for uncertainty. So you might say, “We don’t know what technologies they’ll have in 2015. We don’t know how much difference we can make to their lives.” Those things are reasonable. But otherwise, suffering is just as bad, whenever it happens. We shouldn’t discount just because something is future.

Audience 8: Thank you. My question goes a bit into the line that was asked before about focusing on the easy problems. Especially in the healthcare sector, we see people doing exactly this, calculating the cost-effectiveness and then all the money goes into three diseases and vaccinations because these have the easy technical solutions. But focusing on these diseases leads to destabilization of the health systems because they don’t get as much attention and the governments are also kind of compromised into focusing only on these diseases and vaccination. So you could say that you’re actually harming the healthcare system by only looking at the greatest cost-effectiveness. How do you see this?

Singer: I don’t see that you’re harming people by focusing on where you can do the most good. Now, it’s true that sometimes you get kind of campaigns about particular diseases, and you actually have more money going into them than is required, or you have money going into them which could be more cost-effectively used elsewhere. I think that’s particularly true when you have a condition that is likely to affect people in African countries as well. So we had a lot of money going into ebola once it became a risk that this could spread to the affluent countries. There was very little money going into it before.

We had a lot of money going into HIV, perhaps for the same sort of reason, when in fact it was shown I think pretty clearly that in terms of cost-effectiveness you could do better treating other diseases that were getting neglected because of the focus on HIV. So I don’t think the problem is putting money where it does the most good. The problem is that you may get money going into these things even at the point where because so much money is going into it you’re no longer getting the same value for each unit of money that you’re putting into it. And certainly at that point it should be changed.

The broader question about infrastructure I think is a little harder to talk about, but I don’t think these organizations should be taking money away from existing infrastructure. They’re either providing particular task, meeting a particular need within that system, and they certainly should be trying to promote infrastructure in general in countries that have poor healthcare infrastructures.

Audience 9: Hi, thank you very much. I was wondering how effective altruism takes into account the structural deficit that capitalism has inevitably brought about and continuously is bringing about. Reallocating capital that fuels this system that generates a problem, how do we tackle this? How do we redistribute in a way that is going to be horizontal as opposed to vertical?

Singer: That’s a very big question that you’ve raised, of course. And really I don’t have an answer. And I don’t know whether anybody has an answer. I mean, certainly we’ve had over the past couple of centuries many proposals about better forms of distribution than capitalism. Some of them have been implemented in various ways. Some very harsh ways, as in Stalin’s Soviet Union, let’s say. Some in much kinder ways, as in the Israeli kibbutzim movement. But actually, none of them have really proved to be all that successful. Even the kibbutzim have basically seemed to have failed. Some of them still exist, but they certainly no longer arouse the enthusiasm and commitment that they did in their earlier years.

So I don’t think anybody really has the answer, and I don’t think it’s a reason therefore for not continuing to do the things that we can see are doing good. If somebody comes up with a good answer that looks plausible, and if they come up with a way of saying, “…and here’s how we can implement it,” even given the existing power structures (Obviously you’re going to get a lot of opposition from people who will lose) then, let’s talk about it. But if it’s just a vague idea that somehow capitalism is a problem and we ought to get rid of it, I honestly don’t think that’s a very practical suggestion.

Warburton: I’m sorry. I know there are other people wanting to ask questions, which is a great compliment to Peter, I think, for giving such a stimulating talk that’s making us all think very hard. Just before we thank Peter, I want that Sam Hilton’s going to come in a minute and make an announcement about the effective altruism group in London. But now can we just show our appreciation for Peter Singer. Thank you.

Singer: Thanks very much.