Some of my artist friends think what I’m doing isn’t art, and I’ve given up on art. It’ll take care of itself. You know. I mean it’s always been there, it will always be there, and we always know that new art never looks like art at first, ever. So why should this be any different? We just have to trust the process. And I would say that must be true for every other discipline.

Archive (Page 2 of 3)

Over the past century, we’ve been to the moon, we’ve split the atom, we’ve sequenced the human genome, but were still only at the very beginning of our understanding of the human brain. This is one of the great challenges that we face. If we can understand the brain, we can develop better treatments for brain disorders, we can design better robots, better computers, and ultimately we can better understand ourselves.

We know very little about complex financial systems and how systemic risk, as it’s called, is computed and how you would manage policies. And if you look back at the financial crisis, you can either say, as many economists do, “It all had to do with badly-designed rules,” which may be part of the story; it’s certainly part of the story. Or it may have to do with the interaction of those rules and human nature, like mortgage broker greed, optimism… And you see it not just in individuals who now have houses and foreclosure, but at the highest levels.

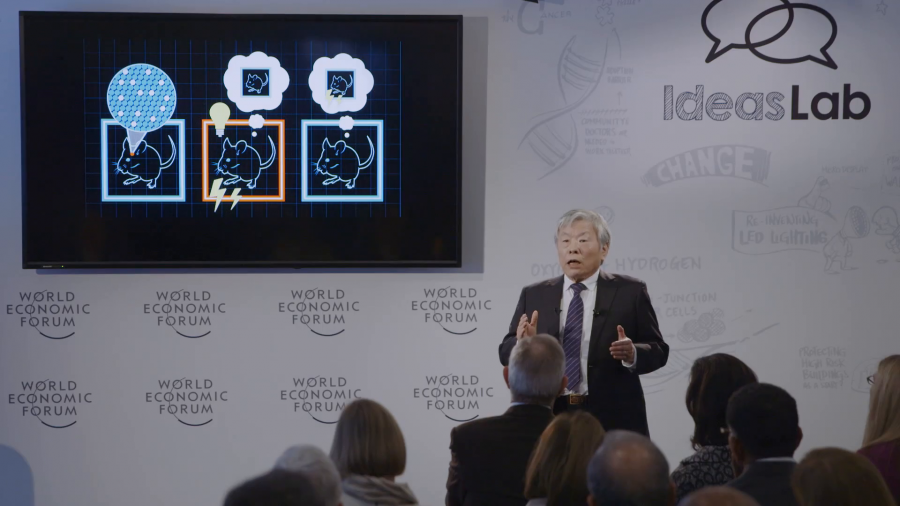

The key molecule of optogenetics is a light-sensitive protein called channelrhodopsin, which is extracted from green algae. Scientists can insert channelrhodopsin into memory cells. Subsequently, scientists can even activate these with blue light which they deliver deep inside the brain with optic fibers.

The face is a constant flow of facial expressions. We react and emote to external stimuli all the time. And it is exactly this flow of expressions that is the observable window to our inner self. Our emotions, our intentions, attitudes, moods. Why is this important? Because we can use it in a very wide variety of applications.

If we want to continue increasing the performance of our computers, we need to rethink the way we compute. And our brains are wonderful proof that impressive computations can be carried out with a very low power budget.

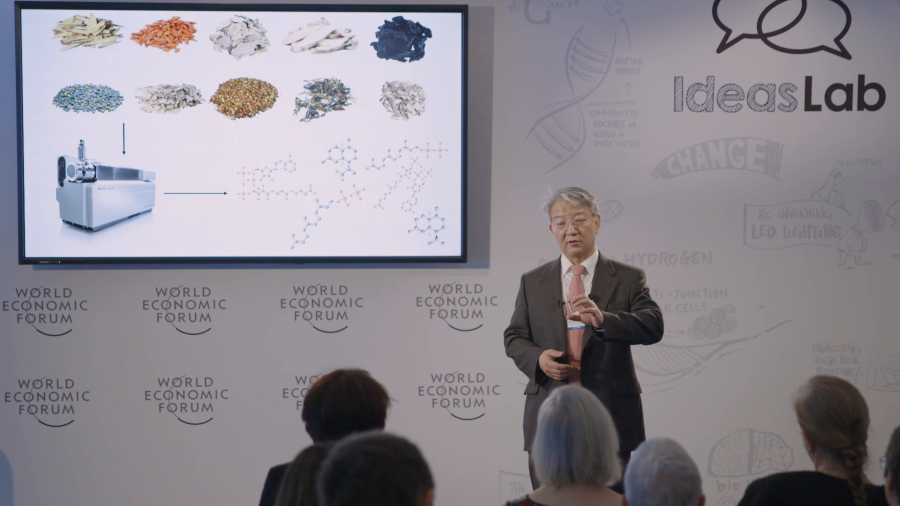

Why are natural compounds better than synthetic chemicals to treat diseases? We have intensively analyzed all those known compounds in the natural products, and found that these compounds have higher similarity, especially structural similarity, to human metabolites.

When lower primates form a hierarchy, those at the bottom undergo a change in their dopamine system. This makes them more likely to consume drugs in an addictive fashion. Now, if this turns out to be true of our species, that would mean that human beings are particularly vulnerable if they’re in some way dominated or don’t have any power.

What we’re trying to think about now is, take the sort of venerable light bulb and recast it as a computational appliance. So, how do we take something that’s been so remarkably successful and infuse it with computational abilities?

How can we extend what we are learning about how simple local interactions in ant colonies or in brains, in the aggregate, produce the collective behavior of the group and the way that it responds to changing conditions? How can we extend what we’re learning about collective behavior in other systems to begin thinking about collective behavior in human social organizations?