It’s not the strangeness of new technologies that frightens us but the way technology threatens to make us strangers to ourselves. In a semi-Freudian spirit, then, I’d like to propose that where Frankenstein and its spawn are concerned, our fear of the unknown may really be about our discomfort with knowing.

Archive

Victor’s sin wasn’t in being too ambitious, not necessarily in playing God. It was in failing to care for the being he created, failing to take responsibility and to provide the creature what it needed to thrive, to reach its potential, to be a positive development for society instead of a disaster.

Mary Shelley’s novel has been an incredibly successful modern myth. And so this conversation today is not just about what happened 200 years ago, but the remarkable ways in which that moment and that set of ideas has continued to percolate and evolve and reform in culture, in technological research, in ethics, since then.

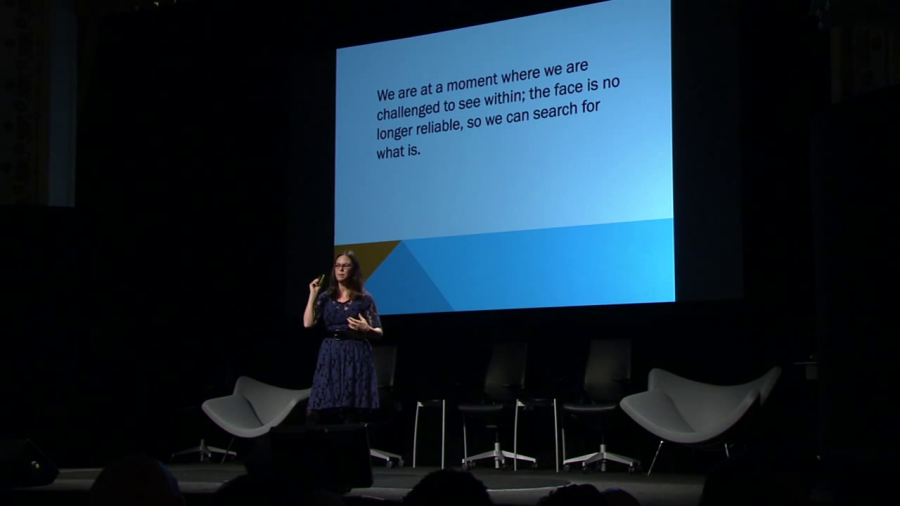

The French philosopher Immanuel Levinas has taught us that it is through our interactions with the face of somebody else, it is through encountering the face of another, that our responsibilities to someone else arise. You cannot look at somebody else, truly look at them, and then walk away without having some kind of sense of a relationship towards that person. But what if the other has no face? What then? Or what if the face of the other is actually the face of another person entirely?

We have to be careful about distinguishing between mere analogies linking the Romantic period to our own age that maybe don’t have any useful analogs, and those that do have some continued operational relevance. Because it is the case that Romantic writers like John Keats, Mary Shelley, William Wordsworth, philosophically modeled and to some extent thought through many of the debates and issues that we’re currently having as we seek to shape the contours of our future societies.