It’s been really interesting to see the entire world pay attention to one topic. This is something somewhat unprecedented. We have had outbreaks in the era of social media misinformation before. Zika in 2015, Ebola 2018, right. So there have been a range of moments in which diseases have captivated public attention. But usually they tend to stay at least somewhat geographically confined in terms of attention.

Archive (Page 2 of 3)

The premise of our project is really that we are surrounded by machines that are reading what we write, and judging us based on whatever they think we’re saying.

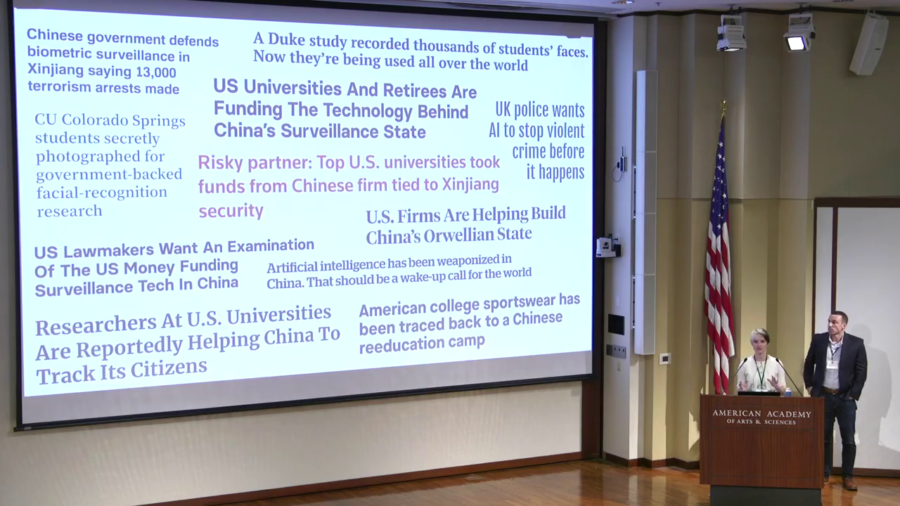

We wanted to look at how surveillance, how these algorithmic decisionmaking systems and surveillance systems feed into this kind of targeting decisionmaking. And in particular what we’re going to talk about today is the role of the AI research community. How that research ends up in the real world being used with real-world consequences.

Positionality is the specific position or perspective that an individual takes given their past experiences, their knowledge; their worldview is shaped by positionality. It’s a unique but partial view of the world. And when we’re designing machines we’re embedding positionality into those machines with all of the choices we’re making about what counts and what doesn’t count.

AI Blindspot is a discovery process for spotting unconscious biases and structural inequalities in AI systems.

I start the story in 1819 rather than 1980. And that allows me to do some very specific work, which is to talk about what I think of as the deep social programming of the tools that we’re now using in public services across the United States.

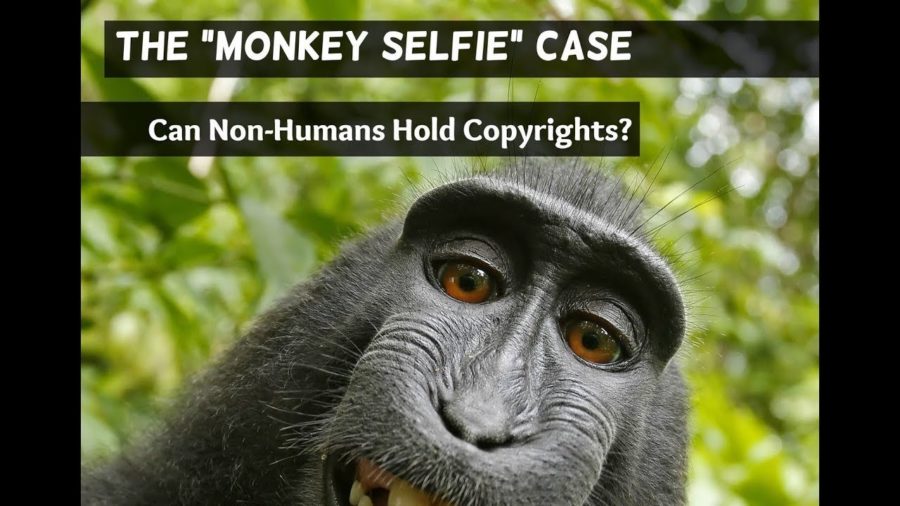

Naruto, then 3 years old, came up and picked up one of his cameras and started looking at it. And he made the connection… By Mr. Slater’s own admission he made the connection between pushing the shutter release button and the change to his reflection in the lens when the aperture opened and closed.

I’ve experienced first hand the challenges of trying to correct misinformation, and in part my academic research builds on that experience and tries understand why it was that so much of what we did at Spinsanity antagonized even those people who were interested enough to go to a fact-checking web site.

What is it about our brains that makes facts so challenging, so odd and threatening? Why do we sometimes double down on false beliefs? And maybe why do some of us do it more than others?

I actually come at this with a set of questions for folks here. Because before we get to the action question I have questions about the broader problem, right. So when we’re talking about truth and truthiness and in media, I think we first have to ask whose truth matters, and what are its boundaries.