Molly Wright Steenson: Hi everybody. It is great to be here. I got to speak at the very first Interaction in 2008. And after running the awards for two years with Thomas Kueber and Rodrigo Vera, it is so awesome to be back here.

I wanted to start out by saying that I’m not an ethicist. But last year I had a really pretty amazing opportunity fall into my hands when I was awarded a named professorship in ethics and computational technologies. And what this give me an opportunity to do is focus a little bit on the question of ethics for the next few years. And one way that I also tend to study things, I think I should point out, is through pop culture. So let’s see where this is going.

Who here knows what the trolley problem is? Can I see a show of hands? Okay. It sounds like some people know it, some people don’t. If you do know about it, maybe you’ve encountered it in…say I don’t know, an undergrad philosophy class. It goes like this.

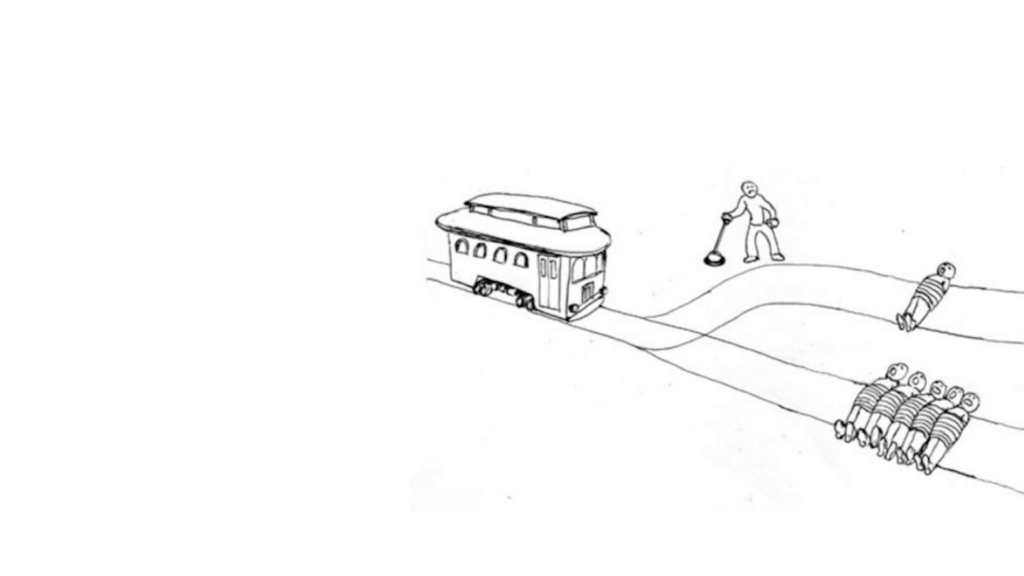

There is a trolley, and it’s hurtling down the track. And there are five people tied to the track in front of the trolley. And you are the person who can access a switch and throw the trolley off that track and get it away from the five people. But in so doing, you kill one person.

What’s the right thing to do? What do you think? Who would throw the switch? Okay. Who would not throw the switch? Who would say this is intractable and like, we can’t figure this out? Uh huh. Right. Okay.

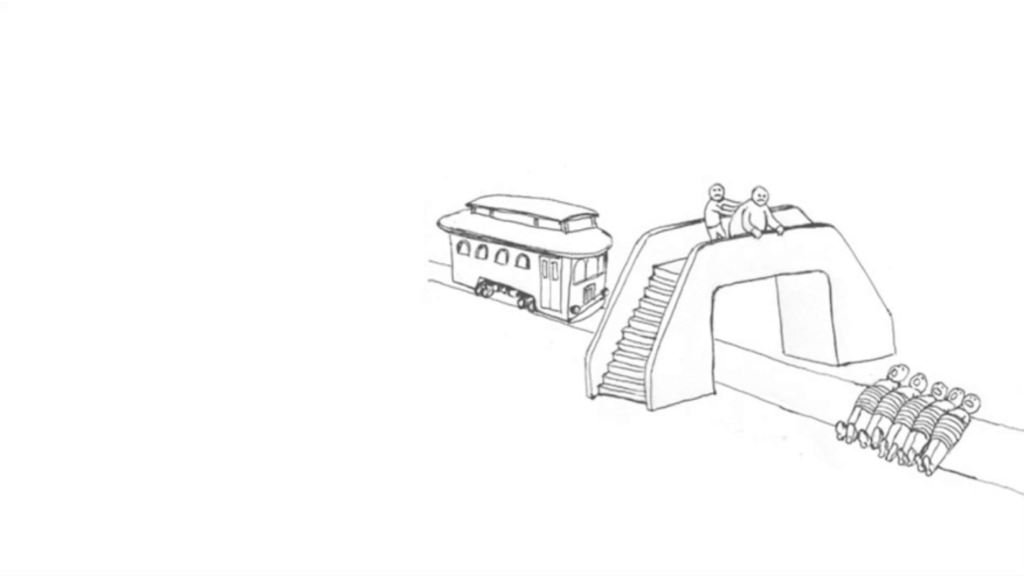

Well then there is another version of it. So what if there’s a bridge and you are on top of the bridge, and you know that you can stop that out-of-control trolley from hitting those people if you throw something heavy off the bridge.

And next to you is a large person.

Okay, how many of you would throw the person off the bridge? A couple of you. And like 99% of you wouldn’t.

And so the reason that we talk about the trolley problem is because of two philosophers, Phillipa Foot and Judith Jarvis Thomson. Phillipa Foot came up with the trolley problem in 1967, and Judith Jarvis Thomson introduced some of the variations, like the “fat man” variation as she calls it, in 1985. And the reason for these experiments, these thought experiments, is because they’re an opportunity to look at the how and the why of some of these ethical and moral dilemmas.

You might also know the trolley problem from the show The Good Place—are there any Good Place watchers out here? [some cheering from audience] Alright. Ted Danson, everyone’s favorite god, or demon depending on your point of view, and Chidi’s very confusing—he’s the guy in the middle looking absolutely shocked as he’s driving the trolley. He’s an ethics professor who’s trying to make all these humans better humans.

Now, there are lots of memes about the trolley problem. These are trolley problem names from a Facebook group that landed there after 4Chan. I’m really happy about my trolley problem guy mug that I finally hunted down and got.

And this is probably my very favorite trolley problem meme. It’s a cliché, right. I mean, the thing about the trolley problem is that we use it a lot when we talk about the tradeoffs of artificial intelligence. Or what we knew would be inevitable when a self-driving Uber hit and killed a pedestrian, right. These questions of is it right to kill one or the other, how, and why? What are the moral considerations.

Now, the Markkula Center for Applied Ethics at Santa Clara University has some really useful thinking and curricula around ethics. And you’ll see their URL pop up at the bottom of a couple of slides. I really strongly recommend that you check out some of the things that they’ve put into use.

But one of the things they point out is that what ethics is not is easier to talk about than what ethics actually is. And some of the things that they say about what ethics is not include feelings. Those aren’t ethics. And religion isn’t ethics. Also law. That’s not ethics. Science isn’t ethics.

And instead they say in terms of what ethics is is typically…you could kind of simplify it down to five approaches: utilitarian, rights, fairness, justice, common good, and virtue.

So utilitarian, hey! it’s trolley problem guy again. And in this case, the utilitarian version is a question here of what is going to cause the greatest balance of good over harm. And in classic utilitarianism, it’s not only permissible but it is the best option to throw that switch and kill the one person versus the five. And the question here of course that we end up asking is can the dignity of the individuals be violated in order to save many others. Do you sacrifice one for the many, if it’s for a much greater good? That’s classic utilitarianism.

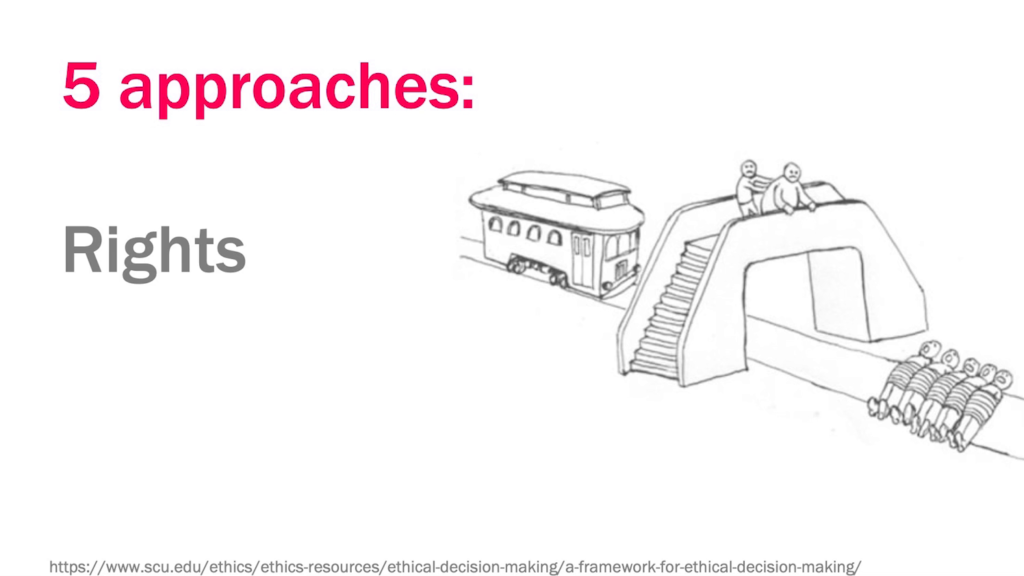

The rights approach, that’s Judith Jarvis Thompson’s question. Is it infringing upon the rights of other people? And in this case it is a pretty big infringement on the right of the large person standing next to you on the bridge if you throw that person over.

There’s the question of fairness and justice. Aristotle talks about equals among equals and privileging equality. So that’s what we’re talking about with the fairness and the justice approach to ethics.

There’s a common good approach. Somewhere here in the audience is the Dimeji Onafuwa, who was my PhD student at Carnegie Mellon. He talks a lot about commoning. What is common to us all? The social relationships that bind us. If we value those, then that’s a common good approach to ethics.

And then finally, virtue ethics. Or as this particular memes says, “As you’re experiencing the trolley problem you ask yourself: ‘What would the chill guy at the bar do, from the Interaction party?’ ” And in this sense, this allows us to live up to our highest character potential. That’s the operating from a virtue ethics perspective. Five perspectives.

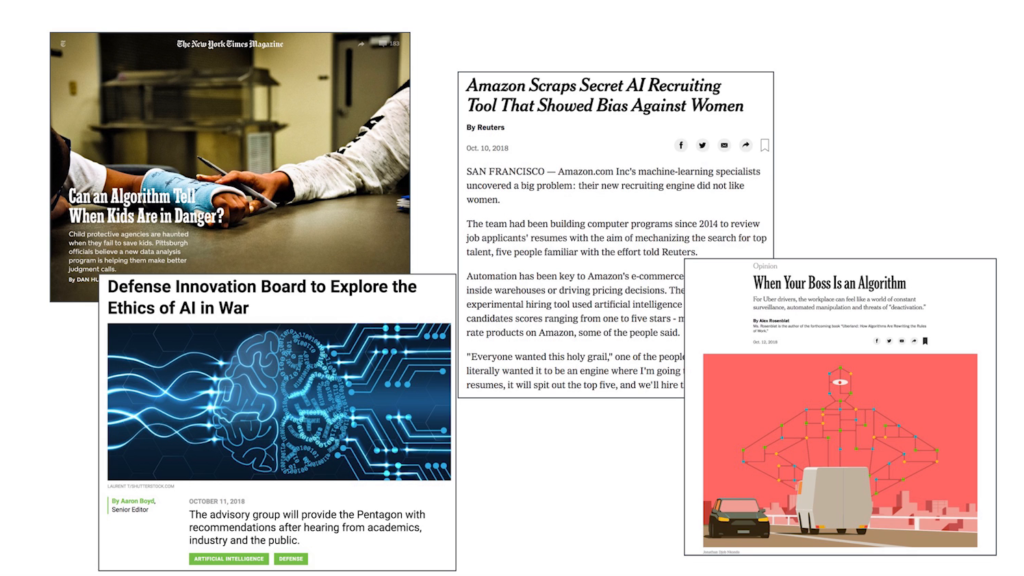

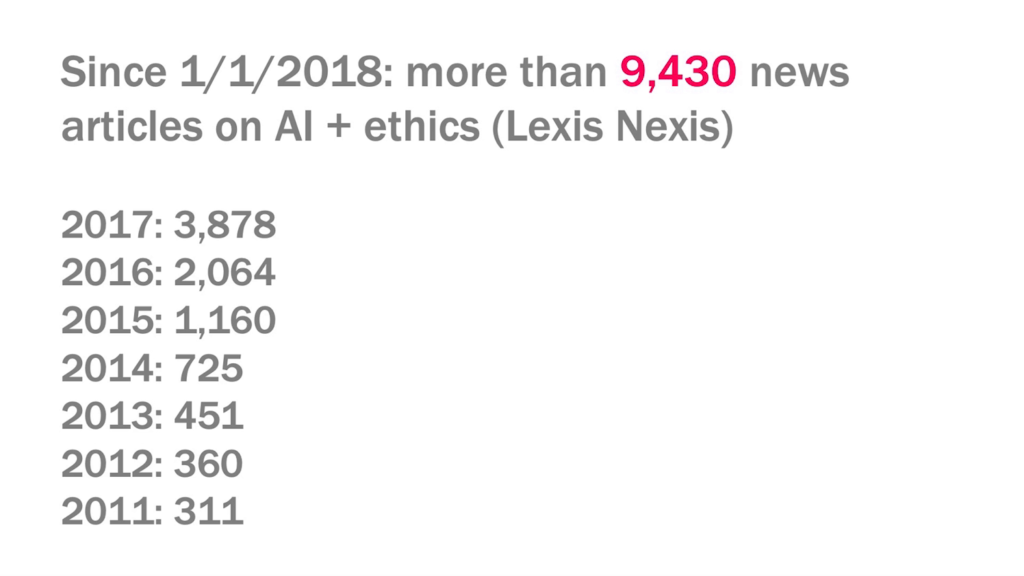

Now, I don’t know if you guys noticed this… I think I did, given the amount of energy that we’re looking at here, but. 2018 and ’19 seem to be the year/years of ethics. And, I just did a cursory look on Lexis Nexis to see if we looked at AI and ethics together, how many articles have been published, and to see how that changed over the years. And it’s almost 6,000 more articles since 2017 about AI and ethics, down to 311 in 2011. So, it’s booming.

So why now? Why now? Okay, we know why now, because some really bad things have happened that need some ethical consideration. But part of me wonders a little bit if we’re in a moment like 1999, when clients heard the word “usability” and then they’d say things like, “We need some usability with this web site.”

It didn’t need usability, what they needed is good design. They needed good function. They needed to be understood. And I kind of wonder here if we need some ethics with this artificial intelligence.

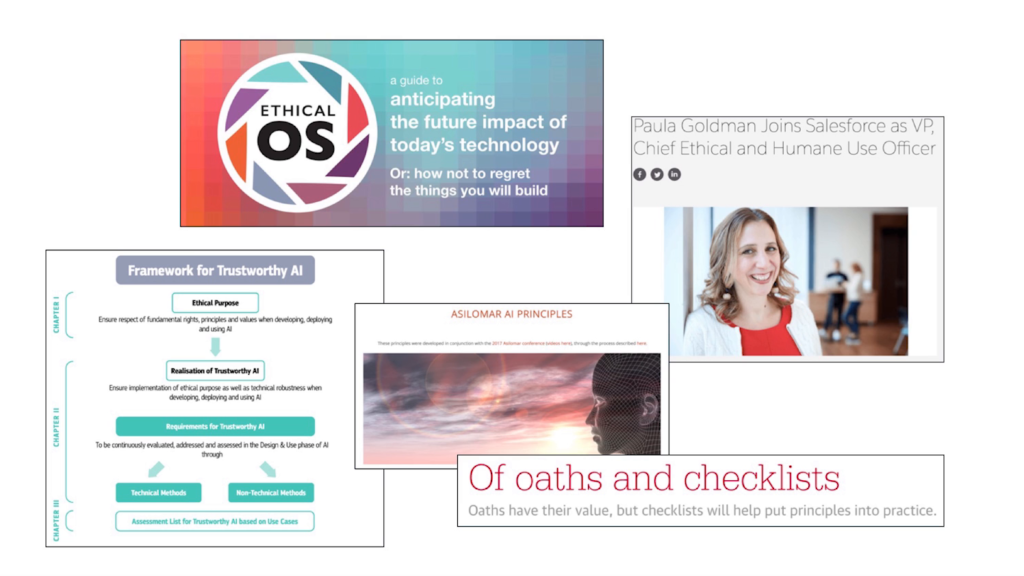

So, I want to point out that Kathy Baxter, who’s the Architect of Ethical AI Practice at Salesforce and someone who’s very passionate about ethics, has collected at least fifty different ethics frameworks, toolkits, principles, codes of conduct, checklists, oaths, and manifestos. And she actually points out that the number may be—she heard from someone else that the number may be like two hundred now.

And here are—you know, you can see some of them here. There’s the Ethical OS that the Institute for the Future puts together. You can see that a company like Salesforce has supported ethics in a number of ways, not least because of their recent hire of Paula Goldman as Chief Ethical and Humane Use Officer. “Of Oaths and Checklists,” it’s an editorial by O’Reilly. There are the Asilomar AI Principles that were put together by a community. And the Framework for Trustworthy AI in the EU.

I want to point out that there are physical ethics frameworks right here in the building. This is Microsoft’s area. I like thinking of it as a very nice ethics hut. And if you can stop by I think they’re going to have six different opportunities to use their game, this card deck called “Judgment Call.” So do to stop by and check out what they’re doing over there. It’s an interesting way I think to have a conversation around a literal physical framework of ethics.

I wanted to put up the faces of some of these people who are both inspiring me and helping me with some of this work. Kathy Baxter is on the one side of the screen, and Josh Lefevre and Louise Larson are Masters students at Carnegie Mellon. And they have been working through a number of these just different ethics frameworks to figure out what they do and what they don’t do. Who they serve. What they don’t serve. Who their audience is. Whether they even define ethics. Ethical frameworks are a good thing. How do we know if they’re good? Or if they’re even ethics? And again, some of these—in fact the majority of them—don’t include a definition of ethics. We don’t know what they’re starting from.

And I want to point out that these tools are useful. They provoke thought. They build community; this is a community, here, that’s come together today and to listen a little bit, to talk about these questions.

These tools offer guidelines. And they help us figure out things like fairness. How to account for privacy. How to keep people safe. How to provide protection against unintended bias, or discrimination.

Last night, this was what Ruth Kikin-Gil said when when we were having a beer. She said, “As a designer, I feel like my job is covering technology’s ass.” And I think that’s because design is where the rubber meets the road. So how can design help? And I’m going to provide a couple of high-level things and show a little bit more detail, and then kind of come back around to some of these other questions that we’ve looked at as we close.

We know that design is good at framing problems. And that designers are good at investigating the context of a problem by using human-centric approaches understanding the needs of multiple stakeholders. But I think there are other things that we can do. We can be directly involved with data, and I really appreciate Holger’s talk because I think he showed a number of the ways that this is very much the case. What and how data is to be collected is after all a design question.

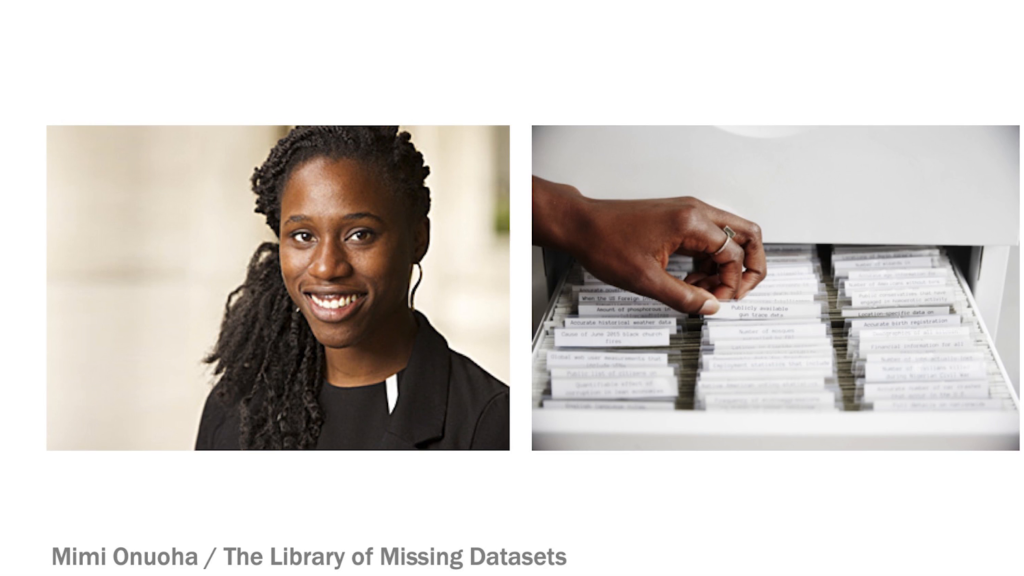

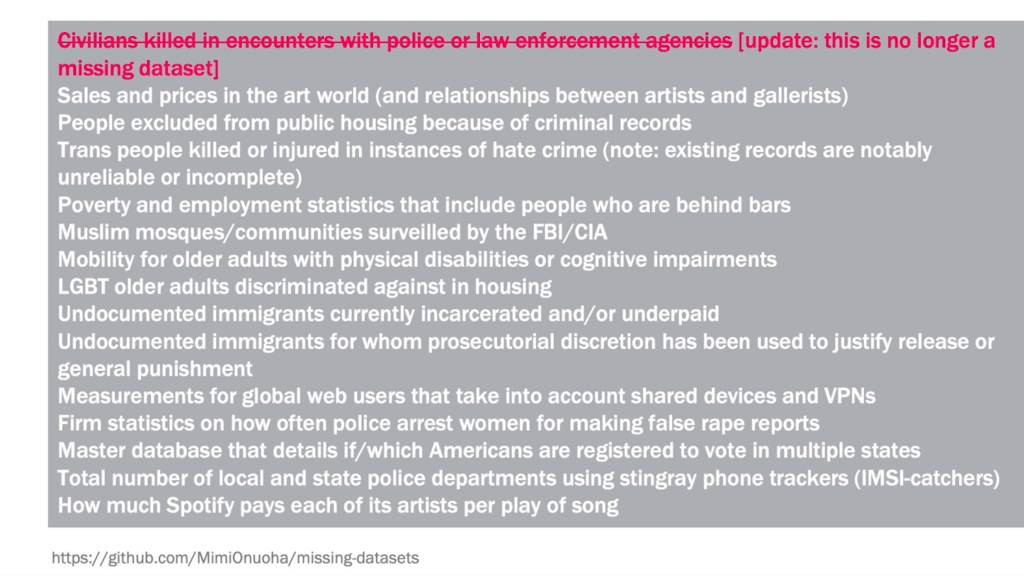

I want to introduce you to the work of Mimi Onuoha—if you’re not familiar with her she is…she’s terrific. She’s a designer as well as a critic and an artist, and she does a number of things like studies how data collection works. And in the project The Library of Missing Datasets she came up with a list of sets of data that hadn’t simply been collected. And if you flip through these file cabinets you’ll discover there’s nothing in the tabs and drawers.

She’s keeping a Github repository where people can actually submit data that hasn’t been collected so that it might be. And indeed one of the datasets is no longer missing: civilians killed in encounters with police and law enforcement agencies. Someone collected that dataset. When you collect data, you can have action.

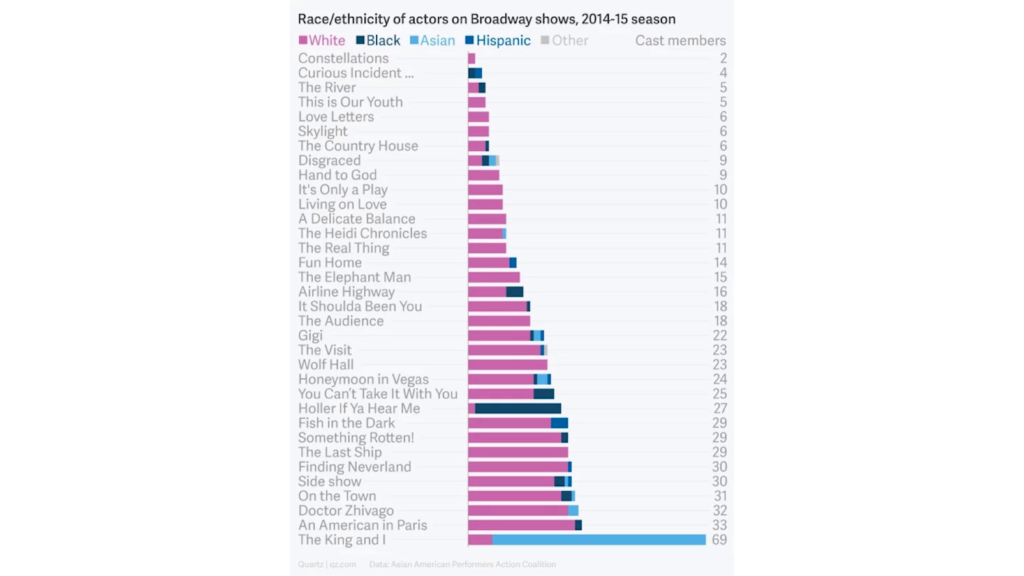

She tells a story about working with a group of Asian actors on Broadway who pointed out that they weren’t getting cast in very many shows. And so she did some data collection with them, and this is what she found.

The King and I is the show that everybody is cast in and there’s not much going on anywhere else. But by visualizing this and collecting it and telling the story, change could be made. And I think again, Holger really nicely said this in his talk.

And of course… I almost think this is a corollary; it’s not four, but it’s maybe 3a, how data is visualized is definitely a design question.

But also I think there is a notion of design for interpretation. And this is a question of something out there. People talk about the black box, where we should be able to see inside and see what the algorithm is doing. Or a robot should be able to be stopped at any time and announce what it’s doing. And we know that it isn’t that simple. Because people who do this research don’t know themselves what is happening, what the algorithms are doing.

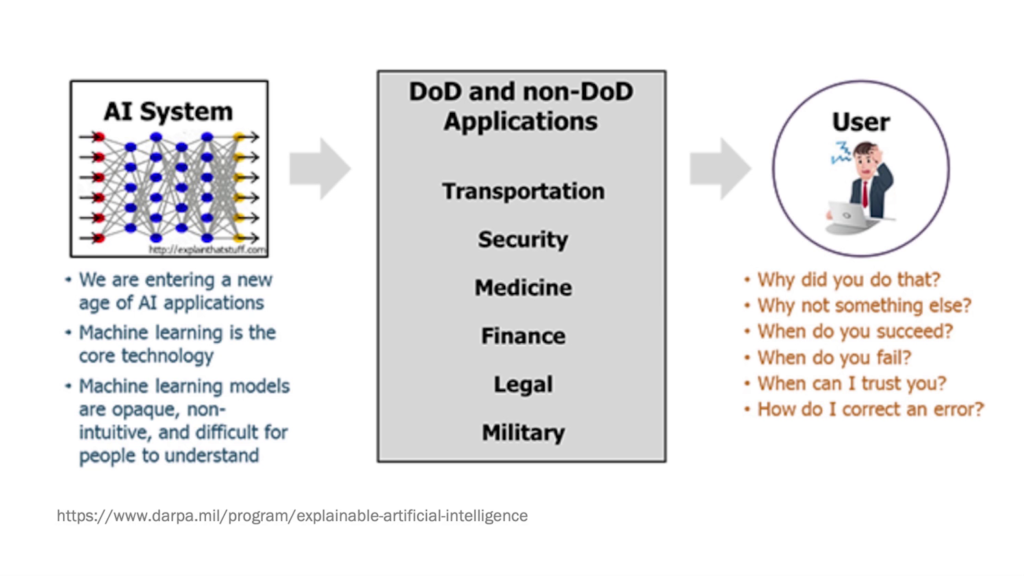

And so this is a question of design for interpretation, versus design for explainability, or design for transparency. And let me explain. The Department of Defense is running an initiative, DARPA is running an initiative, called Explainable AI. And in this situation they talk about entering a new age of AI applications. And that in between, we don’t really understand what’s happening and so we need to find ways to explain it.

I gotta tell you, this image doesn’t give me hope. Then again I mean, we all know how the military is with PowerPoint, and it’s a very very strange thing.

But instead if we’re designing for interpretation rather than transparency I think we begin to get somewhere, and this is something very important that we do as designers. My friends Mike Ananny and Kate Crawford wrote a piece a couple years ago talking about the ten things that being transparent can actually do. Transparency can be harmful. I mean, if anyone ever tells you everything they really think about you…it might not be good. It can intentionally confuse things. And it can have technical and temporal limitations, to name a few.

So instead they say what we need to do is we need to design AI in a way that makes us interpret, gives us the tools to understand what’s going on and why. And this question of interpretability I think is important when you start looking at the complex issues that are out there in the world. There are examples like the Allegheny Family Screening Tool in my Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. And this is a tool that will determine whether a child is at risk from being removed from their family when a call is made to Health and Human Services about child safety, whether there’s a risk of that child being removed in the next two years. And on one hand, it’s probably really good to have an algorithm that does that crunching for you and that figures it out. But we know that the way the data is collected may be biased. And we know that they may be biased against underrepresented minorities. And who is going to be more likely to be in the Allegheny Family Screening Tool, it’s going to be those very underrepresented minorities.

So to this end I actually think it’s pretty impressive that Carnegie Mellon, the Department of Health and Human Services, and a couple of institutions in New Zealand are working on auditing these algorithms in really interesting ways and working with the communities to understand, and to kind of come to a conclusion about what we do with life and death questions where algorithms could help and they could also really hurt.

And we see other things. We’re at Amazon right now, Amazon had had an AI recruiting tool that was really really biased against women. And so the company dropped it. Or you might see the book Uberland; this little screenshot of When Your Boss Is an Algorithm is a snippet from that book, and it’s again looking at the stakes of something like Uber and what it does to the people who drive for it. And I’m happy to see that the Defense Innovation Board is going to explore the ethics of AI in war. Because that’s really pretty important.

So, we know they’re about at least fifty if not 200 different ethics frameworks. And what we don’t know is are they proven? Do they work? How would we know? Here are a couple of examples for you. I kid you not, from our friends at the Department of Defense, this is the logo for Project Maven:

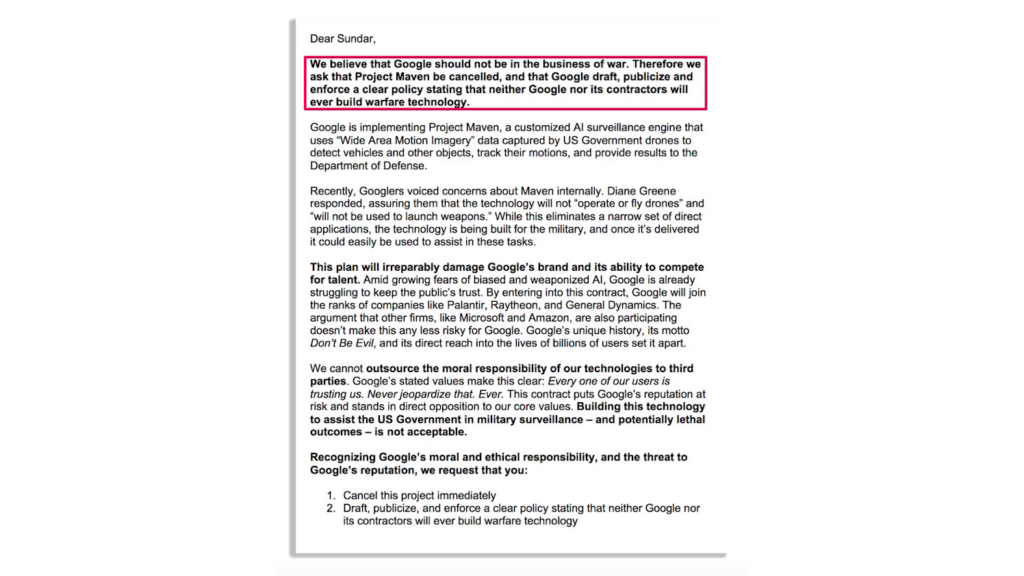

Okay. Just, just look at it again. Um…I’m not—I’m really not sure what’s going on there. But if you recall, you may remember that Google employees fought back against Google working with the Department of Defense on Project Maven. Project Maven is computer vision analysis for drone targeting and could be used to kill people.

So, 4,000 or so employs at Google signed a letter, and they said, “We believe that Google should not be in the business of war. Therefore we ask that Project Maven be cancelled, and that Google draft, publicize and enforce a clear policy stating that neither Google nor its contractors will ever build warfare technology.”

As a result of that, Google published its AI principles back in June on the Google blog. And they’re pretty simple, and they don’t go very far. Which is a pretty standard critique of them. But there were principles in place that said “Okay, we won’t do Project Maven but we may still be doing defense work as long as it isn’t going to be potentially killing people on a battlefield.” I want to point out also that six months later they’ve just recently in December published an update saying that they’ve been working with the Markkula Center for Applied Ethics, and they’ve also brought in a group of internal and external experts to help advise them on what to do.

Other companies have made other decisions about working with the Department of Defense. Both Microsoft and Amazon doubled down on their commitments to defense work. I point this out not to say that one is the right answer versus the other. We don’t have a field of AI without the Department of Defense and without what it’s done to support it in its earliest years back to the 50s and 60s. We don’t have that and we don’t have the Internet. So everything that everyone in this room is doing for a living is somewhere tied back there to something that is defense-funded. And I think it’s difficult to keep these two things in mind, but I think it’s important.

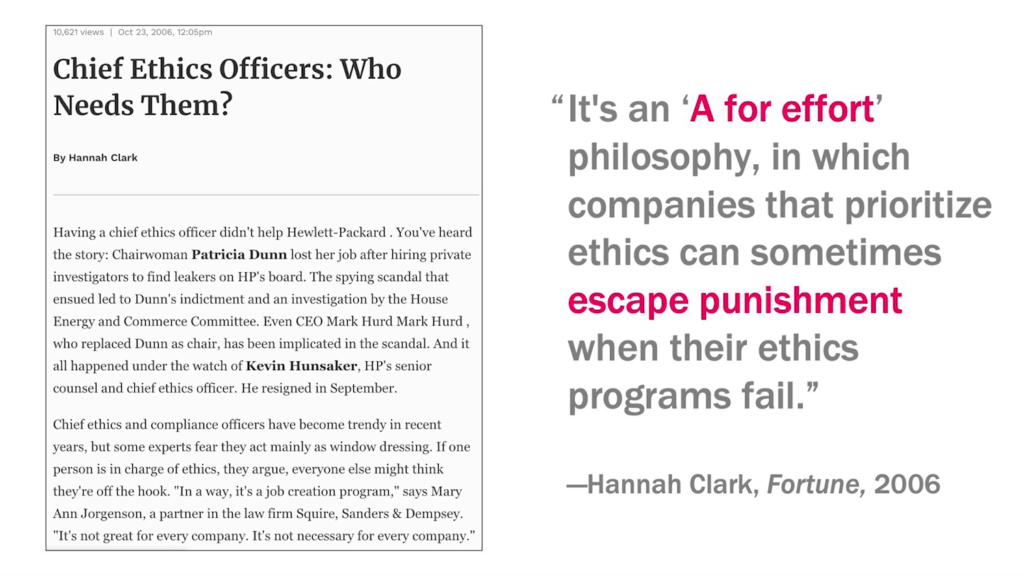

I also have a concern about ethics being used as window-dressing or as a mask for the misdeeds of companies. And this is a quote, and this is something that I also initially became aware of through Kathy Baxter, a 2006 article in Fortune about what happened with ethics officers in 1991. When federal sentencing guidelines changed, the Chief Ethics Officer all of a sudden became a position that a lot of different companies had. And the reason they had it was because it made it less likely that they were going to be terribly punished for white collar crime. So ethics can be a hedge against litigation, and against regulation. And I know that that question of regulation is a major one for companies like Amazon, and Facebook, and Google.

Sometimes ethics is about checking boxes. I was talking to a professor who is at NYU, and he’s just written a book that will come out—I wish I had it off the top of my head—that will come out in this fall, about African Americans and the Internet and technology. And he said that someone asked him, “Is there a checklist that I can follow? To make sure it’s okay?”

He’s like, “No, there’s not a checklist, it’s called very hard work.” And I’m concerned that some of these checklists are just kind of a case of if we have some ethics on this web site, if we have some ethics on this AI, everything’s gonna be fine. Something called ethics-washing or ethics-shopping, as Ben Wagner who’s a professor in Vienna calls it. Do we just find the right framework and put it on our product, or put it on our practices and feel like we did it? Is it sort of like sustainability and the green movement in 2004, 2005?

And a really big question I have is if 2018 and 2019 is the year of ethics, what happens in 2021 when ethics is no longer a hot button topic? Did we solve it? Is it all better? I think it’s more complicated than that.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-N_RZJUAQY4

14 million views on YouTube, my friends. You don’t hear it because you’re laughing too hard, but he goes, “Uh oh!” And indeed, that’s why I do want us to question what do we really mean when we say “ethics.” Thank you.

Further Reference

Presentation listing page, including slide deck