Forest Young: Thank you so much Sara. And I can personally attest, because I am holding this book here… Which I had to pull away from my 7‑month-old baby who almost ripped this book to shreds because it is just as compelling as an object as it is a series of amazing narratives.

So one of the things, Sara, that can kind of summarize my experience of reading your book as like unto falling down a flight of stairs. It was injurious, I think only to a multitude of calcified notions and distortions that I realized that I was harboring. And as I lay flattened on my back looking up, it was a vantage point and a perspective that I never would’ve been able to arrive at myself. And so I would open with just a feeling of gratitude. A gratitude for that injury, but also just an inspiring way to…to learn? And I think in some ways, for those that hopefully are eagerly purchasing this book as we speak, because as many of you know I don’t give praise easily—it’s maybe a personal defect. So with the highest praise, I think that the book is… I think it’s going to be a pivotal piece within our canon. And I think in many ways you talk about Victor Papanek and Rachel Carson, and I think this will be along that ilk. Because I think it is incredibly generous, and easy to understand, and in some ways that’s its most disarming quality? That you introduce us to individuals, in very intimate stories, and you organize them in this very compelling cosmology of the intimacy of a limb, the tangibility of a chair, the spatial qualities of a room, how we think about and navigate and intervene in streets.

And then ultimately my favorite perhaps is “Clock,” which is maybe something that for both people who are the non-disabled like me realize that in many ways that is maybe my own personal impairment, which is that I’m caught up in the industrious clock and how may I own perception of time is in itself injurious.

But I wanted to speak about something that I think is something we both share, is that I think the reason why your work is so sticky is because you’re very comfortable in gray areas. Which I tend to find very frustrating. I want to snap into a solution, I want to snap into a yes or no, right and wrong. And you don’t allow that. You keep us in this particular frictionful way of perceiving the world, and of course encouraging this kind of plurality of futures. And I’m curious about your path that you’ve taken to arrive at this place, what you call kind of paving a road to productive uncertainty. Because I think that’s uniquely special.

Sara Hendren: Well let me— Yeah, let me go and say a few words. Let me back up and let’s do the slides and sort of orient folks now. And let me put a pin in that question—I love that you’ve opened with it because it has to do with what I’m hoping is in the room today with people who are here.

Let me just say, too, thank you so much Forest for being here today, for reasons that I’ll name in a second. But I want to also just thank the fellows program at New America, and Awista and Peter, Sarah and Narmada who organized today. The fellows program at New America was a crucial bit of support for getting this book done and I just am so grateful for that time, that unrestricted time to think. So thank you for it.

Let’s go if we can to a little overview that— It is a book about design and I want people to just drop in a little bit on some of the stories there. And then I’ll talk a little bit about why I wanted to have Forest here at this moment in New America and for our conversation today. So Narmada could you go to the slides please?

So this is yes, the cover. And if you could go to the next one, actually.

Right. The introduction in the book is what’s borne out in this cover, which is this idea of “misfitting.” And if you saw it in the object that Forest raised, that the type itself is actually too big for the books. So it’s this question, right, of whether the type is too big for the book or whether the book is too small to contain that type. And this is what Rosemarie Garland-Thomson calls the state of disability, which is misfitting. And it’s significant because she says it’s a square peg in a round hole conundrum. Which means not that bodies are broken and therefore fail to come to the world, but that the world is actually shaped in a way that only honors and allows to thrive certain kinds of bodies, certain moments at a time. And so the misfit is actually two ways: between the body to the world and the world to the body. And so it’s actually not clear how you get a better desirable future for a lotta kinds of bodies. It’s not clear that’s the realm purely of medical treatment, right. And it’s not even always wanted. And so the onus is on all of us of course to adapt ourselves to the world.

But we can also actually ask the built world to come a little bit more toward our bodies, and disabled people have been doing that for a long time. So I introduce folks to Rosemarie in the beginning of the book. Can we go to the next one?

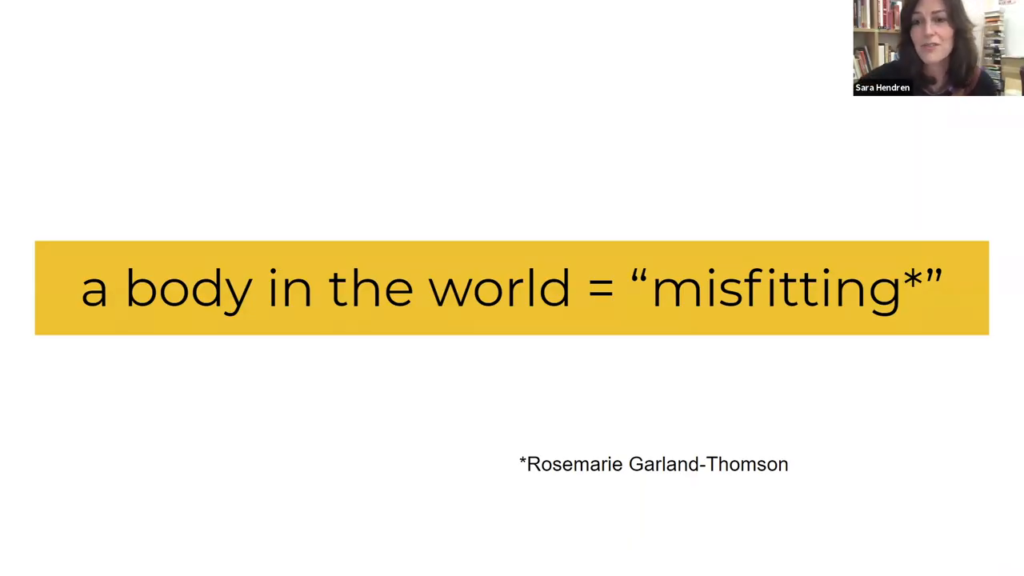

I just wanna drop you in on Chris, who’s here on the right. And Chris is a 30-something white man you’ll see here, who’s at the changing table with his newborn baby. And Chris as you see was born with one arm. And there were half a dozen prosthetic arms built for him in his youth, and folks were quite sure that he would need a prosthesis but Chris, it turned out because he was born this way has adapted to life one-handed quite well.

And we drop in on him at this moment, which is the moment that did call for a prosthesis. Not a universal prosthesis like the one you see on the left. And the other one you see on the left is the overwhelming story about what a prosthetic arm should look like. This idea of replaced functionality, super high-end materials, quite expensive circuitry and so on.

But here we have in this incredibly intimate domestic setting, having built his own prosthesis for just the right tool at just the right time. And that is these soft felt little holsters that hold his baby’s ankles in this incredibly nimble way. So if you go to the next slide.

The question I want for the reader, is to say “What are the replacement parts that would replace the things that matter to me? When my body changes, where is my body in this?” And if you’re someone who uses prosthetic parts already then you know this in your bones, and it’s sort of a compare and contrast with those experiences. But if you’re not somebody who uses replacement parts right now, you might ask yourself when and how would I choose among those things and how would I know? What are the things that matter? So if you’ll go to the next slide.

I place Chris and also a user of one of those super high-tech arms, another man named Mike, among this rich, rich, vast history of prosthetics including the post-World War II phenomenon of rehabilitation engineering, the incredible Audre Lorde who you see on the bottom left who wrote in her book The Cancer Journals about her very complicated relationship to opting out of a prosthesis after a mastectomy on one side. We go to India to look at the incredible Jaipur Foot, which is a low-tech lower limb prosthesis that is designed and built and distributed for free at the scale of a million and half at this point, more. And we meet Cindy who became a quadruple amputee at 60 and has assembled a whole suite of objects.

So prosthetics do all kinds of things, and they are resolutely biopolitical. And we’re seeing this now with the mask. There’s never been a more biopolitical prosthesis than the mask right this moment. But prosthetics, and disabled people know this well, have been biopolitical and in our lives in complicated ways for a long time.

So what replacement parts would replace the things that matter. If you’ll go to the next one.

Another idea in the book is what does it mean to dwell? How do we think about independence, for all of us, in ways that change over the lifespan? If you’ll go to the next one.

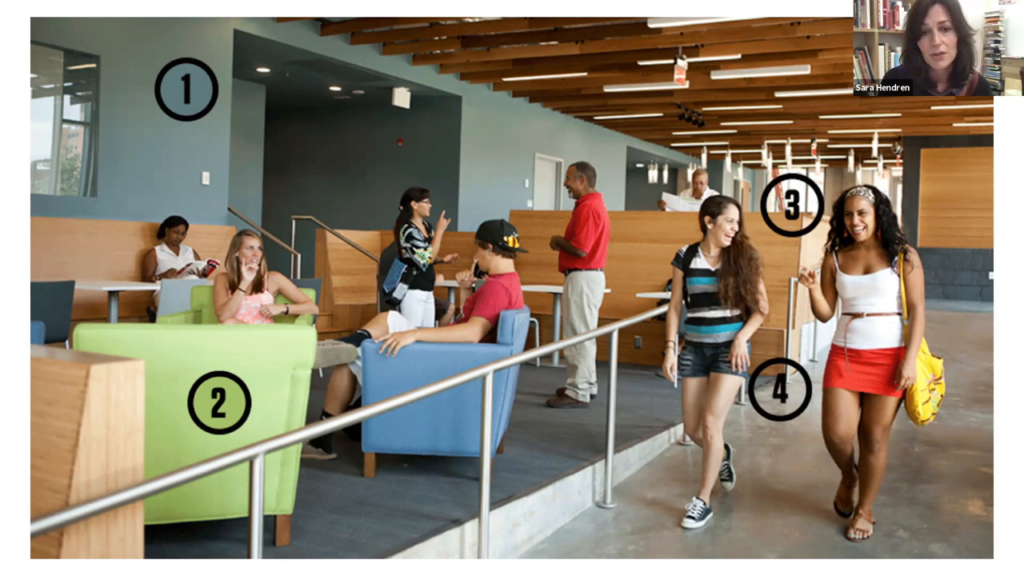

We drop in in this chapter to Gallaudet, which is there in Washington DC—I think we have a lot of Washington folks on the call—which is an all-deaf campus. And what we’re looking at here is the lobby of a dorm space that’s built around a whole program, and architectural program called DeafSpace. And it is not an architecture to create the conditions of hearing. It is in fact a whole envelope, as architects would say, around the beauty and the integrity of the visual language of sign and the kinda embodiment of deaf experience. So we’re looking at a number of people in the lobby, sitting and signing to one another over these half-height walls that create really long sightlines. It’s a beautiful sunlit interior with a long ramp down the right. And these solid greens and blues are there in place of bright white or prints because they make for ideal contrast for skin tones of various colors to do the fine work of visual signing. So go to the next one.

So, it’s a question about how to do well, right, in the spaces we’re in. What makes for the condition of dwelling and thriving? And that chapter goes on to chronicle a famous civil rights leader, Ed Roberts, who you’re looking at on the left as a black and white photo of two white men in college who were also wheelchair users, Herb Willsmore and Ed Roberts. And Roberts on the right was a polio survivor. He used a lot of complex medical equipment his whole life. And through a really interesting, long story that I won’t go into, he was able to work with a doctor at the hospital on campus at Berkeley to live in the hospital room as a dormitory room. And in fact ten or twelve other students in the years after Ed came to campus were able to do so as well. They called themselves The Rolling Quads, and they reinvented a dormitory on campus, that had not been available to them. Had not been available to them. They were thought of as rehab clinical subjects. And here they were reinventing college.

So that became an idea. Like we can actually live, even in a hospital setting, with help, and yet also be the determinants and agents of our own lives. And so they launched the Center for Independent Living and indeed what’s known as the Independent Living Movement. And you’ll see these storefronts still. They’ve been replicated in all fifty states since this history. And they provide referrals for hiring care attendants and outfitting homes and so on for wheelchair use and other adaptive kind of changes. But an idea of independence that has help in it. Not just what we do by ourselves, but an orchestration of help that is a way to dwell. So let’s go to the next one.

Public space is a way of getting into the public sphere. We know this but in disability and design this has been an incredibly important history. If you can go to the next one.

Among many things in the “Street” chapter, we look at the history of curb cuts but we also link it then to what may be more familiar to people in their immediate, which is the tactical urbanism of bike lanes and things like desire lines, the kind of casual paths that are carved in public space. And we think about—curb cuts are so ubiquitous now as to be beneath our notice a lot of times if we don’t use them in a conscious way in a wheelchair. But if roll a stroller over those curb cuts, if you are using a bike, walking a bike or a skateboard, you also participate in a very hard-won politics that was an editing of the built environment, which is stubborn and concrete and doesn’t move easily. But here it was rolled out at infrastructural scale, and that history is just incredible. You can go to the next one.

And finally this is “Clock” that Forest referenced. It’s the last chapter. Which is the hardest conundrum of all, which is to say when’s the design for slowness? And if you’ll go to the next one.

It opens with a profile of the Green Man Plus program in Singapore, which is no more and no less than a transport card that when it hovers over the call box at a pedestrian signal like you’re seeing here it will, on demand, give you twelve or thirteen extra seconds in the crosswalk—just for you, and then it will revert back to its normative time structures. And that was a way for Singapore city to accommodate an aging population that needed more time in the crosswalk. So there’s a kinda material design that’s making the city flex and bend in this really elegant way.

And yet of course slowness is not just a kind of matter of speed and gait, and I get into a little bit of my own experience sharing life with a person with Down Syndrome, my son Graham who’s now 14, and thinking a lot about the history of developmental disability. The design for management of intellectual disability that happened at the scale of institutions and asylums. And a really hopeful story in the end of a kinda service design community service for young adults with disabilities who are making and remaking the world in their way as well. So we can stop sharing now.

I just want to say that the reason why I wanted to ask Forest to be here today and in the context of New America is because I am struggling, yes. You and I, Forest, have kind of inverse roles, where you are very much lodged in industry and you have roles in academia and other kinds of social work that you do on behalf of design and politics. I work in the realm of academia, which has the liberty to be as critical of technology as it pleases. And in fact I am part of many cohorts of scholars who deeply nourished me about all the ways that the excesses of tech need a kind of critique brought to bear.

But I have also— I’m struggling because I’ve also seen a lot of really good design. There’s a story in my book about a man with ALS who orchestrated with a philanthropist and a nursing home director and a bunch of technologists a way for him to live his life with…you know, automated by a cursor that’s mounted on his glasses and a wheelchair-mounted tablet. And what that does for him in the self-determination of his life and the way that he lives, Steve would say…this is him now, not me, that technology is the cure, actually, until medicine proves otherwise. The technology, he would say, is the cure. He’s quite sanguine about it.

And so I cannot afford a kind of either/or, you know: tech bad, politics good. You will find throughout the book if you read it that it is full of politics and movements, for which there is no substitute in rights movements, for sure. And yet the bodiedness of the body does actually ask us what is it that we pragmatically need in our lives, and some of that is better tools and technologies. And some of those come to us by the logic of markets.

So, some of you will be saying like, “Well Sara, yeah, we get it. You need both, right. Or you need something in ‘the middle.’ ” And I am really unsatisfied with that kind of you know…both/and, resting in the middle. I actually think we need more specific and disciplined languages for talking about the worlds that we build. So in my book I reference David Edgerton and “technology-in-use” as a different way of thinking about impact. And I reference Ezio Manzini, who gives us the idea of networked diffused design, for instance. And look at low-tech and high-tech and— I try to do some things but it’s a whole infinite world and I guess I sense at new America there is also this wrestling between where markets do their work and how can we characterize and talk about them. And also, the very real limitations of any designed anything ever, right. That nothing will substitute for a politics.

And let me just say finally— So I want to hear your reaction, Forest, to all that. In any place. But I also wanted to say to the whole group, and including myself, the biggest exhortation to find the agency that we do have, right. Like I teach a bunch of young people who end up in industry or who start in industry and maybe they migrate elsewhere. Some of you have your main post in industry but you are not just the thing that you get paid for. Some of us are feeling quite stymied by the ivory tower limitations of academia, but what are the realms of agency where we can act, perhaps especially in 2020. As family members, as community members, as neighbors, and yes also in our work. So, thanks so much Forest for…just…the leap of faith in being here. Where are you in all this?

Young: Thank you so much. And I think you know, one of the interesting things I think the book does very well is it simplifies…not overly so, but it simply asks us to meditate on and potentially to critique the periphery of this moment where the body meets the world. And I think in an academic setting, the insertion into that conversation is through pedagogy. What are the methods by which we hold up as either exemplars of the way that we should learn or the way that we should teach, and the artifacts that we hold up in high esteem. And pedagogy itself of course is, and rightly so, has been incredibly scrutinized over the last year. You know, speaking as a designer and in design education, so much of design of course stemming from this modernist notion of form and function, or as you kind of quoting Heskett of the squaring of utility and insignificance, is really looking at a specific Western or European cannon coming out of the Bauhaus. Of course teaching at Yale, where Josef Albers was the head of the School of Art, they’re it’s still steeped in modernism or you know, post-modernism or some type of tense relationship with that idea of form and function.

I think in terms of pedagogy, what’s lovely about what Sheila de Bretteville’s brought to the program is this idea of what Paulo Freire would call that the pedagogy of the oppressed. To specifically talk about the purpose of education, specifically design education, it’s not to be overly smitten with the commercial viability of one’s work. And I think that’s very…sometimes problematic for critics that come in to see a graduate critique and they’re trying to in some ways initially validate the work based on some type of commercial criteria of viability. And then ultimately realize that it’s really a conversation around ideas? And specifically, a uniquely self-possessed way of understanding their own kind of hard-fought perspective on an idea, and their hard-fought way of saying, “This is the way in which I want to make this idea real.” And understanding that there is a buffer between that conversation and that conversation of kind of commercial viability.

I think it’s fascinating to think about, when you talk about crip time which I think is my favorite aha moment in the book, which is in some way we’re all enslaved to this industrial notion of measuring ourselves based on efficiency. Even whether or not I go into the three-year program or the two-year program in graduate school. Who’s getting an internship versus who’s getting a job. How am I progressing through that job. And in some ways all of these platforms that are well-intentioned… You know, seeing at LinkedIn that someone got a promotion, realizing am I keeping pace with that person. And so this competitive mindset ends up always—you’re kind of keeping this competitive mindset at bay I think, also as an educator as well as a student.

Hendren: Yeah.

Young: And I do think that what’s interesting by shifting between the spaces of academia and industry is that I’m realizing that there is sometimes this unwelcomed insertion between body and world of commerce. Does the body actually needs this. Was the body actually asking for this. And is this something that is you know, an empty promise, or it’s inserting kind of a selling proposition versus a true kind of service proposition. And I think those are the things that I continue to wrestle with, but I think that you’re right to be troubled by in some ways, what is the pure conversation of body and world, but then what are these kind perversions of that pure conversation that are these considerations of market, or even educational viability. Maybe pedagogy is even in some ways a perverse insertion to some degree.

Hendren: Yeah I mean, I think… It’s so interesting what you say, and in my own work with students at the pedagogical moment a lot of times we’re working with disabled artists, for instance, who are asking for a very particular, very expressive design. So we’ve worked with Alice Sheppard of Kinetic Light, who is wheelchair user and a dancer. And Alice wanted a ramp built, but not a ramp for getting into a building, she wanted a ramp for stage. And so people have said to me about this pedagogical thing, right, “My students are gonna go into industry. They’re not actually going to be asked to make raps for dancing, probably ever again,” right. That was quite a unique experience.

And I’m wondering if it’s not easy for me to think that yes, full stop, I’m fully aware that they’re going to go into industry and mostly into software. Because it’s the reigning work of our day. But that they have had an encounter with Alice that was outside the logic of the market, and that encounters and relationships—especially the conviviality of building something together—and I have never seen anything more convivial than that. You and me and this thing that we’re building together. Because it trains our eyes on this thing? but in fact the work is happening between and among us. And my hope is that students having had that encounter with Alice where they were having to dial back from all their notions about what they thought wheelchair use was, whether they thought Alice’s life was kind of sad and oh, they discovered she’s a real dimensional human being with all kinds of experiences. And what they thought engineering could do in the world. That then, five, six years hence, they are making the software, somebody has a question about whether a blind user is going to be able to navigate this thing. And because I’ve had the encounter with Alice and maybe several others, they don’t hesitate to get on the phone and called the Association for the Blind down the street.

In other words they’ve gotten over the awkwardness of thinking… I think a lot of people, rank and file, are trying to do well. But if they don’t have it in their mind’s eye for one thing, it’s an unknown unknown, right. But also the awkwardness of say, what if I do it wrong? What if I offend someone? What if I completely backfire this engagement? I keep thinking, have I built enough trust that you’ll make the call.

And then I also think, is it naive for me to think…you know, folks doing design at your level, Forest, it is a human set of decisions, isn’t it? Who’s in the room? Who’s asked the question? I mean, I have students, alums from Olin, who went into industry, got a little disillusioned with it, went into tech policy, and then also felt like, “Oh, you know what? I can actually be more effective if I’m actually in industry. It’s a tradeoff. It’s not really clear where my politics would show up.” So again, how does that land for you?

Young: Yeah no, I think you bring up some very interesting things that also make me…excited but also skeptical in the same degree. One is I actually think that the speed in which—you know, either the speed of technological innovation, or the speed of kind of technological convergence in all these kind of adjacent technological areas are becoming these kind of monolithic platforms. But in some ways the “jobs,” or the problems are either so complex or they have never been seen in quite this embodiment.

So the way to prepare for those…in some ways I think a lot of that you’re talking about in your book is this tradeoff between bespoke and kind of mass production. And in some ways, I think education was seen as valid, right, from a pedagogical perspective, if the thing that you’re encountering is a simulation of the thing you’re going to be experience—or be paid for. But more and more so, it’s impossible for education to prepare for the things most of my students are going to be facing, even two years out.

And so in some ways this destabilizing, convivial approach to solving…you know, and acquiring this kinda plasticity of mind, is going to be the new requirement. But it’s still…my skeptical side is that’s a new requirements still within the realm of commerce. Like commerce will demand that plasticity and adaptability. But I do think in some ways…your book proves out in many meaningful areas that it’s from technology-in-use, but also specifically talking about insertions of like an oblique angle problem that get one to truly fundamentally free themselves from the entrapments of a historical way of solving it. Which still would be market-viable, because you’re still talking about “disruption”—

Hendren: [mirrors Young’s air quotes] Yeah.

Young: —or differentiation. So I think the amount of slippage between something with high integrity and something of market viability I think that’s becoming incredibly nuanced.

Hendren: Well, and I don’t know— I mean, I would push back on whether that’s a new thing? So here I want to invoke the great Danielle Allen, political philosopher who writes a lot about education and for whom the horizon of education, the goal, is what she calls “participatory readiness.” Which yes, can include professional readiness, but supersedes professional readiness. That participatory readiness is the enduring invitation of an education. That you arrive in your life ready to be a civic actor. And of course that is in a new way complicated by…certainly in our own country the cost of higher education and so on.

But Allen has also accounted for a lot of people’s objections to this about you know, economic mobility and what seems like the…we should just hew to professional readiness on a certain kind of politics. And she’s like no no, it’s precisely right if we want a genuinely equitable future that participatory readiness remains our horizon. So right, when I give you the example of my student going to the company and making a “better” decisions, still within commercial viability, I hope I’m thinking about one feature of the way academia and industry interact. I hope, in a much bigger way, that when my students are talk—when I’m talking to them for four years and getting to witness their lives at that moment that I’m doing what teachers have always done, which is to try to make some space for them to become whole people. And there again, the conviviality of building something together can be part of that thing. Mostly because it’s the relationships and how do we make space for our best work, and what does it mean to negotiate our conflicts and become surprised by one another and un-curate our experience, and all those things that education has been doing for a long time and should continue, right.

I mean, would you really put a… I mean, I just don’t know how historically new the “learning to learn” as opposed to learning the next software language, you know what I mean? That’s always been like, super quickly outmoded.

Young: I think that’s— I mean I think it does have kind of a… It’s been kind of historically perpetuated but I think that the transparency that so many of these digital and kind of Internet windows have given us is the realization that—and I would hold myself accountable to some degree…the lack of participatory readiness I think I would say maybe in some kind of educational settings is the buffering between commercial viability and the space of ideas.

And why I say that I’m on the fence about whether or not that actually is encouraging participatory readiness is I think that the example that Amanda shows in terms of crafting this lectern is she’s incredibly persuasive. And one of the things I think that art schools struggle with is how can one be persuasive. And it feels alien in the context of you know, kind of right-brain pursuits to be able to toggle between a kind of a fantastical notion or a self-possessed vision, and the ability to then put yourself in the shoes of somebody who has to accept that vision or has to agree to it. And that specific negotiation oftentimes happens “in the professional context.” How do I pass through the gate of “convincing my team” that this idea has viability and merit? How do I convince the client partner that this idea has merit and addresses some of their concerns that this made thing will be something that will be painted in a picture of success. And ultimately, how can there be a kind of a viral narrative that they’re able to tell to their kinda managerial ladder.

And I go back and forth on that. Because to your point about policy, making something real or translating an idea into a made thing…has an outsized degree of persuasive tactics attached to it, where the made thing we romanticize because it’s about you know craft, and it’s about form and beauty, and it’s about significance, and then artifacting the body in question. But how can “convince” someone that this is an artifact that should be welcomed? And that’s where it feels alien because it feels like selling is creeping in to the conversation. But I think that’s where I see participatory readiness… You know, I’m skeptical about it in some degree. Because I think in the realm of ideas, how can I “convince” a room of something. And it may be that in art school it’s the realm of everyone’s idea is kind of perfect, everyone’s idea is theirs. But there may be a moment where you and I are talking about where I actually think the majority people are truly fundamentally wrong. And how can I…move this needle. And I think that’s an interesting space that we find ourselves in.

Hendren: Totally. And so as you say, it gets close to selling. But it also—and my colleague John Adler who is an expert in narrative identity and all the ways that we biologically need stories in our lives to make literal sense; I mean just at the hard-wiring of how we operate. And he said to me reading the book like, “This book is so much about stories, about narrative.” And I wanted to say that [Allen?] in her kinda three-part like—what makes participatory readiness, she describes something called “prophetic reframing,” which she talks about like that’s the role of words and rhetoric and stories. And so if you look at Dr. King—I mean you look at the way folks used the reframing gesture to tell a different story.

So I mean like, you could say yeah, sometimes are we collapsing to the persuasion of selling. But sometimes are we using language to re-story what the world really is, you know. And I do feel like in this book…it hangs very much on stories, you know. Like why should you look at Chris’ little prosthesis for a newborn? And you know, you might look at that and say, isn’t that so plucky and clever of this man to do that. And I’m like no, it’s in a whole array of prosthetics. Let it live there. And let it actually change who you are, and your relationship to the help you’re getting with the tools that you use every day. And if we see that connection and that continuum, then we see each other a little bit differently. I mean I’m counting on that kind of…the reframing work of the objects. But I’m glad that you kinda got me there.

I’m just looking at the time. It seems like maybe we should cross over into taking some questions, do you want to do that now?

Young: Absolutely. So, Jennifer asks, “What do you think of the idea that because of the risk of COVID, we are all experiencing—and not to make light—an ambulatory anxiety that has resonance with the experience of disability, unsure how to move around others on a sidewalk, unsure if one can use the door handle to open a door safely.”

Hendren: Yeah, very much so. And if you look at Alice Wong… So Alice’s book is here. I’ve got it with my other ones. I’m in like a family tree of wonderful disability books that have come out this year, and Alice is the editor of this one. Alice has been saying now throughout COVID that disabled people are a kind of oracle for the moment. Not happily so, but turns out in point of fact they are. So in other words, disabled people have had to think for a long time about immunity, about exposure, certainly about the relative friendliness of the built environment and their relationship to other people. So Alice offers us that metaphor, sort of like these are best resources.

I actually think that’s true in general. It’s acutely apparent right now, but I do think that disabled people— In ten years of doing research and collaborations and being mentored, I’ve learned to see disabled people as doing the most creative work that is also the most urgent work of body meeting world. And I think it’s really critical to keep both of these things closely together, right. So in other words, we can say oh well, disabled people are oracles and therefore it’s really urgent because we feel 2020 is quite urgent. But I want people to never forget the deep creativity, the creativity of that. Of reshaping the built world. So if you’re walking around in your neighborhood and you’re thinking right now about what are restaurants doing to kinda spread out into the street, and what’s gonna make a friendlier city for all of us, and what about telehealth that’s now getting fortified a more robust and people been asking for that for a long time. Ask yourself if you could employ that same generosity and also attribute the creativity— not just the urgency but both of those things together. And point other folks to this long history and say disabled people have done it before. They have been here and done that, right. And it’s not a matter of being just inclusive and not forgetting those folks. They are the first experts we should call on. So, you’re absolutely right. There’s a connection.

Young: We have another question from Sophie, who asked, “Are there specific countries that are closer to realizing your ideal world built for all bodies? And where does the US stand in comparison to achievements in this area relative to other countries?”

Hendren: Oh my goodness. I don’t know that one could generalize from countries because…right, disability gets at the very notion, the very cultural notion of living with assistance from one another. So think about how different the United States is. Its kind of organization around nuclear families as opposed to extended families, which is much more the norm, right. And the way that older people, older adults and older family members are treated all of the world. I mean the West is the vast exception in utilizing nursing homes, for instance. So just on those grounds alone we’d find infinite variety and we’d never—

I mean, I will say in the treatment of older adults it’s pretty clear the US is not doing a great job, right. So I think we could sort of…if we’re gonna say a blanket kinda thing, we’ve normalized sort of the management and housing of older adults in a way— And I understand why people do it. It’s a consequence of industrialization, and this kinda foreclosing around the nuclear family and so on. Nonetheless, right, if you look almost anywhere else you’ll see a richer life in terms of aging.

But you know honestly, in my own travels I see some cities that get it really right when it comes to streets. Other places in terms of special education do incredibly sophisticated work. It’s just too vast to say. But I guess I would just offer that good ideas happen in a lot of places, and here’s again where I live in that tension between the research lab and the policy kinda think tank, and also the industry kinda driven ideas that arrive for us, from lots of sources, in lots of forms, iterative and infinite in variety.

Young: I’d like to encourage all the listeners just to continue to ask questions. These are great. An anonymous attendee, thank you, asks, “What about when a body meets the natural world?” I think that’s interesting. It says specifically the natural world. “Is the natural world creating misfits?” I think you know, from the man-made world to the natural world. I think it’s an interesting distinction, so interesting. “Any natural design lessons to learn from?”

Hendren: Yeah, interesting. I mean this is where it sort of goes back to… You know, there’s a reason why…sort of thinking way way back and kind of like how do we recognize a human, that tool use is—not the only… There’s sociality and other kinds of things that we would mark at the sorta key moments of ancient human life. But tool uses one of them because why? We need just a sharp edge to actually manipulate reeds for weaving, and the animal food that we would’ve eaten in our bodies, and making fire, right. So in other words the body, as I say an introduction, is probably never not extended? I mean, we could almost— I mean, philosophers argue this stuff way more deeply than I’m going to right here. But we could say that it’s almost unthinkable that you would not need a tool to amplify your reach and your grasp and your engagement with the natural world? Totally. Certainly the built world. So we know that that’s kind of in our DNA and in our bones.

And what was the second part of the question, Forest?

Young: Any natural lessons to learn from?

Hendren: Natural lessons to learn. Oh, that’s such a good question. For how we… Yeah, I mean… Maybe this just goes back to some of the low-tech tools that I profile in the book in different chapters, meaning there’s a kind of— I went to visit at the Harvard archive some ancient ancient tools to take a look at like, how do we recognize you know, just a basic mallet and a sharp edge carved out of a rock. To see the dignity and really the techne, the technology that’s there in all of our stuff. So we can learn in the sense that we can say if we’ve always been doing this, then it doesn’t matter if it’s my pen or my smartphone, but I am getting help. And in my book the people whose design and disability I’m chronicling, their tech is called “assistive” technology. As though this thing [holds up cellphone] is not assisting me in every nuanced way every day, right. And these reading glasses, my very favorite object in the world. So in other words, if we see ourselves on that big plane, the big sweep of history, and also that our fundamentally human state includes needs, and assistance, then let’s make all of our tools actually visible and unifying. Let’s just call it what it is instead of ranking and ordering who’s got the cool tech, and who’s a cyborg sorta futurist, and who’s using “assistive” technology. This doesn’t doesn’t help us in building a collective politics around human lives.

That was a…long answer.

Young: It was a good question. So thank you anonymous attendee. Another person asked, “How do we train ourselves to look at the built world critically?” So Sara, how did you develop this ability to look at the world around you and to say, “Hm, I wonder if this needs to be this way,” ultimately towards making the world a better place.

Hendren: Yeah, what a good question. You know, I think I learned in a very acute way when my son Graham, who’s 14 now, was a baby and he immediately qualified for physical therapy, occupational therapy, speech therapy, all kinds of things. And I learned and… I was with him at the park with him on my hip and people were asking me, fairly regularly, whether I got tested in pregnancy. Like people feel a kind of permission and enfranchisement, when he was that little—and he was right there with me, saying like, “Didn’t you get tested?” you know, like how are you not performing the sort of rituals of pregnancy. And I would think like…really?

And then we would go to the therapist’s office, and there would be all this wonderful gear, or you all these toys and things. So at the physical therapist for a baby, you use all these bouncy balls and these little foam mats and all the kinds of convivial tools, in Ivan Illich’s term, for play. And I thought you know, it’s so interesting to me how the story of who Graham is is just preceding him. Like people are making up stories about him all the time. And I know that these objects are the product of human decisions that are also proceeding from ideas about who he is. And I know better, because he’s in my life, you know. Here’s this singular human, and he was just being mapped by a diagnosis, right. And other identities, folks know this well, right, the kinds of identities that other people are imputing to you because you’re walking down the street.

So, that was a way of understanding the malleability of the built world. But I will also say, being a kinda artist and humanist type working in an engineering school, I’ve never met people more convinced of the malleability of the world than engineers and designers. Because they’re in love with the physical laws of the universe, and they teach me about it all the time. So when you’re with engineers, they will always say “This doesn’t have to be that way.” And I would just say to you, no matter what field you’re in, that remember always always always that despite the black box of this thing, [holds up cellphone] it’s not actually…it didn’t arrive fully-formed. Everything, everything is shaped by human decisions. Which also means that we could back away from it and unmake those very same— Now, it’s not easy. But it can be done. And if you even just build your own furniture sometime, you start to see like, this is how stuff is put together, with intention and decisionmaking. And it means that the plurality is also in front of you. It could be otherwise. So that is one way to do it.

And reading, too, about the popular history of design, you just take seriously contingency and plurality, right. It didn’t have to be this way. And ordinary people, I want to say with this book, should feel the deep stakes in being able to make a claim even if you’re not the expert, right. Like I was quaking in my boots arriving at an engineering school not knowing a lot about the laws of physics, and yet staking a claim as a civic actor, participatorily, because I needed a better built world. So, when you see something wrong, or something that’s a misfit, you can just as a civic actor raise a hand and say, “I’m invested. Why? Because I’m a human with a body in the world.” Okay. Let’s start there. Where are the seams and the cracks? Who might I talk to to move forward.

Young: Thank you. So Meredith asks—you’re gonna love this one, Sara. “Would love to hear about the process of writing the book. Was it hard? What was surprising?”

Hendren: How many ways can I say? Yeah, it was—and God bless my editor Becky Saletan at Riverhead Books for hanging in there with me. It was really hard it was a book that taught me a lot about writing, on a steep learning curve. I really didn’t know— All books arrive in a different manner, I’m told by writers, and this one was very much a grassroots, ground-up. So I don’t even know… I knew that I wanted to do the scale of prosthetics and furniture and rooms and streets, but it took me forever to figure out oh, call it one object: Limb, Chair, Room, Street, Clock. Like just the simplicity of that took forever. Like finally, I’m gonna run every day doing my workin’ it out. And I finally in the middle of that emailed my editor and said, “Oh I think I know what we need to do.” It took us forever to find the title, right, because it is a book about design and disability but neither appears in on the title because we really wanted for people to understand fully that this is not a topical book in those specialty ways but really invites you in a different way.

And it just is like all writing is rewriting. And I just ruthlessly cut some really good stories and things that I just felt like, the narrative needed to hang together. And I found that I loved it. I really did, and…I just can’t express to you how long it takes to write a reasonably short book. That was the other thing I was quite determined to do. So it’s 200 and change but it takes a long time to whack away at it.

But also I’m married to a documentary film editor and producer, and he thinks about story all the time. And so he would say to me, “We need more scenes here,” like, “Where’s the voice of the person.” You know like, he really coached me on all that stuff too because he does it every day, so it was really fun. It was really fun, looking back at it now. But in the early stages it was really hard.

Young: There’s a related question, Sara, from Gracie. “Sara, did you have a particular audience in mind when writing the book? If so, did it change at all between the initial idea and publishing.”

Hendren: Yeah. So, I think I have sort of several audiences in mind, but I did start out at the very very beginning thinking it would be a little bit like a blog that I ran for several years between 2009 and 2015, which is covering kind of prosthetics. It’s a blog called Abler; having a little archiving issue right now but it’ll be back online momentarily. And in that I was covering kind of like well, the latest gadgetry and also, come over here and think about disability studies and disability rights. And it was a way of doing that, and I think I thought the book would proceed from those same ideas.

But the more I read in disability studies the more I realized design is actually just a really interesting, vivid, resonant pathway to these ideas, right, which is about in independence and interdependence. The universality of assistance. The miracle of adaptation—tech or no tech, right. It’s the body, it’s the adaptation that’s really exciting there.

Then I figured out oh right, of course. Design is a way to discover these things, and people actually need to be walked through those things to help make those connections.

And I am imagining yes, a kind of tech and design reader, in the sense of people who read about popular science and people who just are sort of like, they’re interested in tech for its own sake and they would like to be shown a different of kinda thinking about it. So I am thinking of that reader for sure.

And also I’m really passionate about ordinary people, as in the answer to the question before. Ordinary people seeing their own stakes in design and not thinking like oh, here’s a like, expert with cool glasses who can comment on modernist architecture. It’s not that, it’s just like, all your stuff, all your living stuff, right. Engineering is fundamentally applied and so is design. It’s the wedding of utility and significance; that’s John Heskett’s elegant formulation. So what that means is we all have stakes in it. So I wanted that reader who is kinda curious about the built world (there it is in the title) to sort of say, “Oh. Yeah. That belongs to me too.” So the ideas in design theory that are there are… I try to speak in the most plain-spoken vernacular so that you feel like oh yeah, yeah me too.

And then again it’s a lot of stories that are there for the reason that we always read stories, right. Our hard-wiring is to read the stories of others because of course we are then being read by their stories. We are asking ourselves “what happens when my life looks a little bit like this?” or “What happens when my loved ones go through this? What are the resources that would be available to me?” And always, nonfiction or fiction, other protagonists? are the text for our inner lives. It’s certainly true for me and I hope it is for you in the way that folks have done so in this book.

Young: Great. A good question from David—hey David. “How do you see this work impacting current ADA standards?”

Hendren: Well, my hope is—I mean a lot of us in disability and design find to our chagrin that the ADA is often treated by designers and indeed in design schools as a compliance matter? So in other words, here is your genius vision; make sure you run it through these specs so that you don’t violate any laws and therefore get sued. Rather than a moment to say whoa, what’s the opportunity here? What are alternate forms of mobility that might change the very idea of the building itself? How can I resist the temptation to slap a ramp on like an appendage, and start from a kind of—what we think of as a “non-normative” experience, but again that curb cuts show us is not actually non-normative at all. And indeed, how can built space just keep being friendlier for these bodies which are not built of concrete and steel. They are flesh, porous organs, right. So, how can we start with bodies, real bodies, and let that actually be—this is where I mention the creativity and the urgency and I want people to hang on to that. Man do we need that injection of creativity also at the level of ADA. For folks who are planners and folks who are in school. And maybe again, Forest, just to call back. It feels like a pedagogical moment, you know. If in your training you are taught to think like wait, pause, this is actually an opportunity and an opening, not just a closure on our design. But there’s still a lotta…I think Amy [?], scholar, calls it compliance knowledge or compliance knowing, right. That it’s just a whole field of like okay, just make sure that I’m not gonna be sued, instead of the invitation something bigger.

Young: Great. And this is our last question. We have a tremendous amount of questions and just want to acknowledge I’m all those who asked questions that we weren’t able to address in the time that we have but this is part of an ongoing, great and rich dialogue. Awista asked, “What’s the role of public institutions in shaping how one’s body meets the world? We can easily think of failures of public policy, but what are some of the successes? In other words, how do we think about bodies that live in societies with democratic ideals and the extent to which those values have honored those needs?”

Hendren: Yes, Awista that’s a great question. It’s a big one, too. I want to just say that one of the richest ideas that came to me in the writing of this book, through Sarah Williams-Goldhagen, is an idea of a built space as an action setting. So whether we’re talking about a room that tells you what to do in it—so think about a cathedral versus a cafeteria. You know immediately the kinds of behavior, what you should do with your body, how you should feel in that space. Because the action setting is sending you it’s cues. Who can be here, right. What all can you do? How friendly is it, how noisy, how loud? What is the purpose of this?

So, action settings are what I often think of when we think about civic spaces. Not just the public street, which becomes the public sphere—being in public, and again that has to do with curb cuts but also like Gallaudet and getting on the college campus. Action settings in the street itself, but also at the end of the book I invoke Danielle Allen in the scene of a school, a public school—high school, and the service work that these young adults with disabilities are doing to shore it up. I mean in the most practical terms. They are repainting its doors, they are making it lively and worth being there for those young people. And public education is surely one of our most important democratic institutions.

And I realized that you could think of the school, and perhaps the voting booth, and the public plaza—the ever shrinking truly public plaza, as action settings. How can they be action settings? So in their literal physicality but also in the civic messages that they send. Who can be here? What can you do here? What can you not do here? Who decides, and who knows?

But I was so moved by this group of teenagers in that public school, doing the most pragmatic work, and just the scene of what that public school was doing. And this public school, Brighton High here in Boston, has like a classroom that’s a whole store, for free, for students who need canned goods and other kinds of toiletries and things for their house. I mean doing the public work of care, fundamentally. And I loved thinking about that in a different way as an action setting. I think it’s useful for all of us. I hope that answers a little bit.

Young: Fantastic. So we are at time. And I just wanted to use this moment one, to thank you Sara for this wonderful book. It truly—it’s not only captivating but it’s transformative. It was really an awakening for me, and so I’m grateful for you for that. Thank you. And also to New America for putting this event together and all the people that have been assistive in fielding the questions for all the participants who asked such rich and provocative questions here, and also those we didn’t get to address. So thank you all.