I’m here to talk about digital culture, but a strange, very interesting aspect of it: how close it has brought us to nature. How much it has brought us closer to the dream, to the Holy Grail of all designers and architects and engineers and you name it, to do it like nature does because nature does it best.

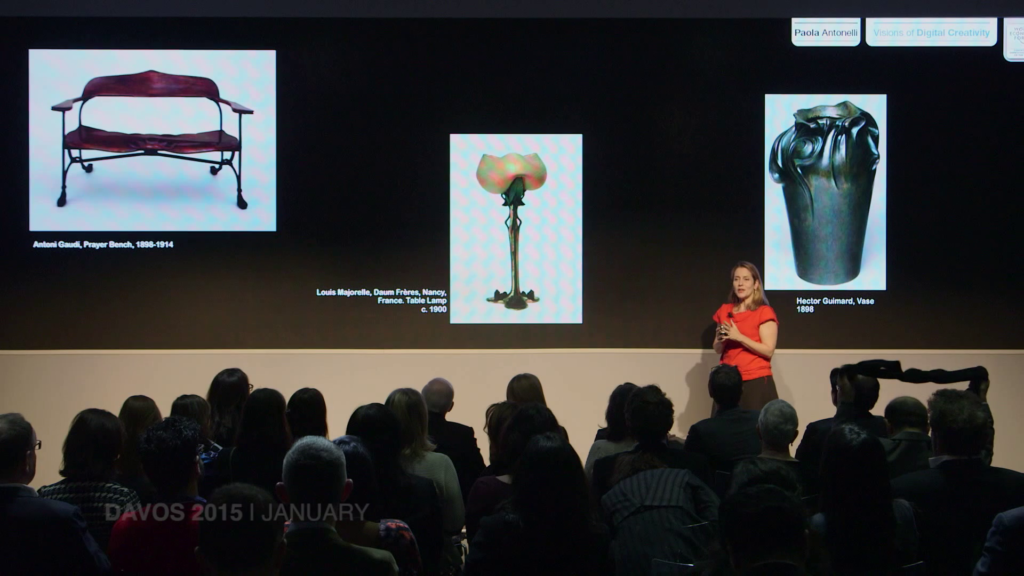

And you know, organic design in history has had so many different notions and forms. If you just look at the collection of the Museum of Modern Art it can see the imitation of the forms of nature by Gaudi or by Hector Guimard.

Or, it can also be the transposition of the forms of nature. You see here some images of digital in the Museum of Modern Art, literally digital. One of the first exhibitions about microchips and diagrams, and then Tetris, that is in the collection of MoMA, and the graphic user interface by Xerox PARC, which we want to grasp for the collection. But this is what I wanted to show you. This is a visualization designed by Martin Wattenberg and Fernanda Viégas that shows the wind over the territory of the United States. Absolutely digitally-founded. It’s about data that is gathered by the government, but rendered in a way that makes us feel that really that’s how nature does it.

And that’s what I love so much about digital culture. Even though it used to be Gaudi and Majorelle, it is also now Neri Oxman and Joris Laarman, who participate in that culture but get closer to it by using the computer. Neri Oxman, who is a professor at the Media Lab, is specializes in observing natural behaviors and transforming them, distilling algorithms and laws from them, and we’ll see more of her work later.

Joris Laarman, great Dutch designer, that’s pretty much the same. Uses software that mimics what nature would do if it had to sustain a human body in a seated position. It’s really interesting because you see it’s so much more than form. It’s thinking of of the systems that nature participates in.

These days, we’re really trying to move the whole behavior of people and the whole sensitivity of people towards a kind of an ecosophy. You see here our food by Félix Guattari, but there are many other people that are trying to make us understand that we have to change our behaviors if we want to recuperate some sort of balanced relationship with nature.

Without modifications to the social and material environment, there can be no change in mentalities. Here, we are in the presence of a circle that leads me to postulate the necessity of founding an “ecosophy” that would link environmental ecology to social ecology and to mental ecology.

Félix Guattari 1996: 264 [presentation slide]

So it’s very important to do it in a way that is also visually convincing, not just morally convincing. And that’s where designers and architects come into play. They’re trying to bring together high and low, computer and nature.

This is a beautiful old-style rendering of electronic pieces of equipment that look like a botanical drawing from the 18th century. And in this case instead, today, the contemporary drawing is a rendering by Daisy Ginsberg of a new branch of science, synthetic biology. The ability of putting together different strands of DNA and then designing new organisms with them.

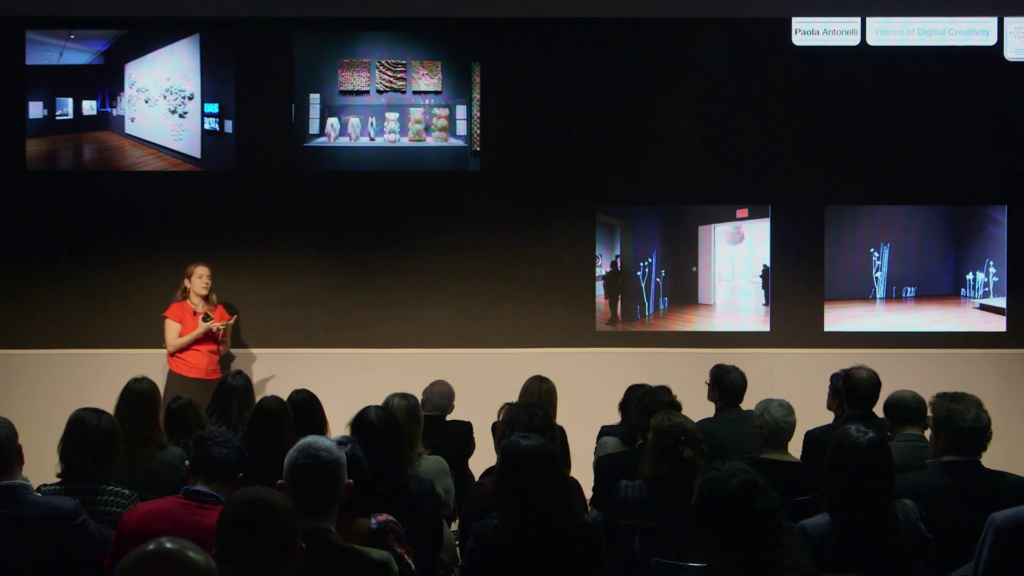

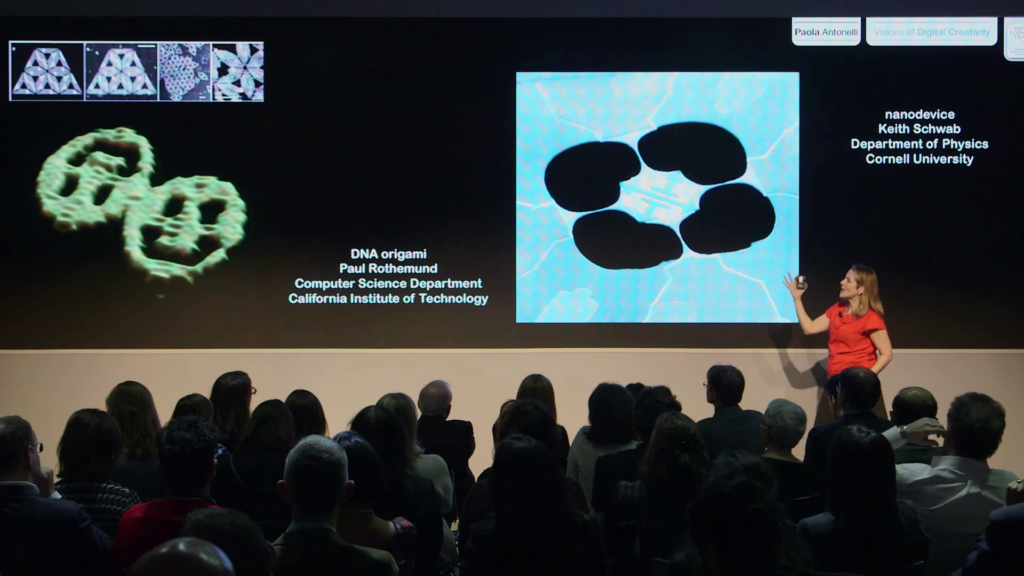

So you see, it’s a flow that has begun centuries ago but that continues today and that has to be understood. This is an exhibition, that together with some of the people that are here in Davos actually, I organized in 2008. It was about design and science, and it looked at all the different scales in which designers and scientists come together and work on nature and try to imitate nature. From the nanos cale, to the 1:1 scale with facades and buildings and other details, to the large scale, large complexity. So, it was a way to really look at the algorithm which in 2008 was of course already well-known, but not yet. The kind of emperor that we see today in so many different disciplines, and understand how it could be used for natural purposes.

So, we see here examples of work by a great scientist, Paul Rothemund who’s at CalTech, that was among the first to do DNA origami. It’s a way to work in biology that has intelligent and smart design applications. Here is the work of a nanophysicist, Keith Schwab, and you see designers start to collaborate with scientists also in the renderings of science. A little parenthesis, scientists usually don’t want to appear elegant and don’t want to have good slides and good images, otherwise they’re not taken seriously. Well, they’re starting to see the propaganda importance of also having good images.

And here, to give you an example of what was happening in that show is the juxtaposition of work by UCLA scientists, a new method to mark proteins not only with color but also with letters (an alphabet soup of sorts), and instead this great Israeli designer and artist that had hypothesized a whole world in which you can put one character into each spermatozoa so that each ejaculation becomes a poem. So completely different, but the two were next to each other in the exhibition and they were hugging, so happy to finally meet for real. So, this is kind of a metaphor of how the future will be. Scientists and designers needing each other.

This is a work commissioned for the show. Two architects, ArandaLasch, working with the scientist, nanophysicist Matt Scullin, who’s now an entrepreneur in preserving energy and who is here. Matt provided Ben and Chris with a nanostructure based on the number six. And on that, Chris and Ben formed the whole law, this algorithm, that is almost like leavening for a landscape that could be both a landscape of a city, or a facade treatment. You see here the indifference to scale that comes from building an object that can grow itself.

And that’s one of the most beautiful tenets of today’s organic design. Designers want to grow things. Engineers and architects want to grow things, not to make them. It’s something that starts from a law that is within, whether it’s the number six nanostructure, or whether it’s crystal as Skylar Tibbetts does at MIT. So, it really is interesting this inner growth is so important to scientists and to artists.

In the same exhibition, there was also this great piece. It was alive. It was called “Victimless Leather,” and it’s by a group of designers and artists that are based in Perth, Australia that is called SymbioticA. It was a little leather coat that was done using stem cells of mice. And it was quite amazing because it was literally done this way. I didn’t tell my MoMA that there would be an incubator in the exhibition, you know, I just like, let it happen. Columbia University colleagues made it go and started it. And then after awhile it became too big and one of the sleeves started dangling. There was an incubator with nourishment. So I called the artists in Australia, and I asked them, “What do I do?” And they said, “Oh, Paola, you have to stop it.”

And I was like, “What do you mean I have to stop it?”

And he said, “Just turn off the nourishment.”

And I’m like, “What? I have to kill the coat?”

And very interestingly, I started having this moral dilemma. I could not really sleep at night. I thought I’m like the Governor of Texas, I have to make a decision of this kind. It was just really quite amazing.

But that goes to tell you the moral dilemma that is instilled by art when it’s well done, or design when it’s well done. And of course when you’re in a moral crisis, what do you do? You talk to the press. And I did. There were some people from The Economist that were taking a tour, and and I told him about it. And they published it, and it started this amazing debate.

So that’s truly once again where organic design today is based on science and based on digital culture, but it kind of needs the latitude of art and of design in order to create real quandaries that we dive into in order to progress in the future.

And there are many many designers and scientists as you know that are working on in vitro meat, which is a very interesting dilemma. I know the most basic question is, if you could grow meat in vitro without hurting any animal and with a footprint that is decidedly less than what is happening today, would you eat it? Is it moral? Is it taste? Is it culture? It’s very very interesting.

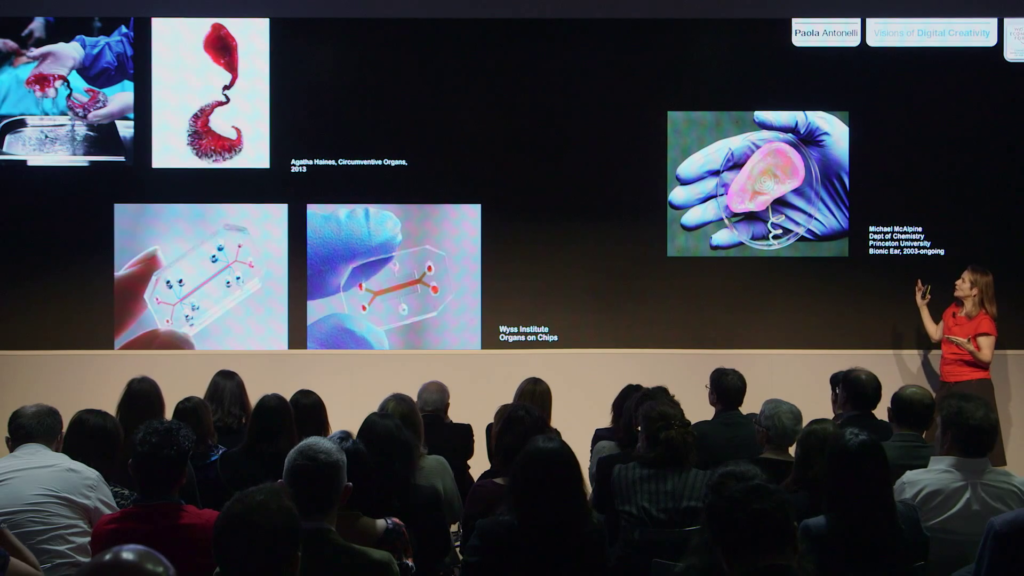

And this happens on an on again also with the imitation of organs and the modelization of organs. I really like what the Wyss Institute at Harvard is doing. They’re trying to simulate organs, like full-fledged human organs on microchips, using some basic cells and some nanotechnology so as to be able to test some medications before they go into trial, and speed up the whole pharmaceutical production process. And of course that’s what artists do. They simulate brand new organs that we don’t have yet, right?

So, you see the juxtaposition. Scientists, quite advanced scientists that are still kind of testing their way…artists. I really like that, because that communication is what brings all the different parties to new realizations all together. So we go back to this idea of the synthetic aesthetic, of adding a new branch to the way we build and do things.

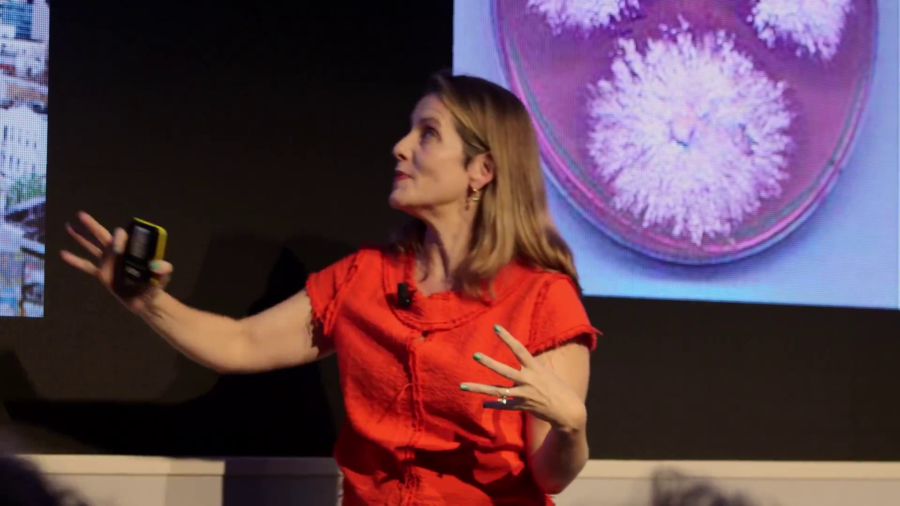

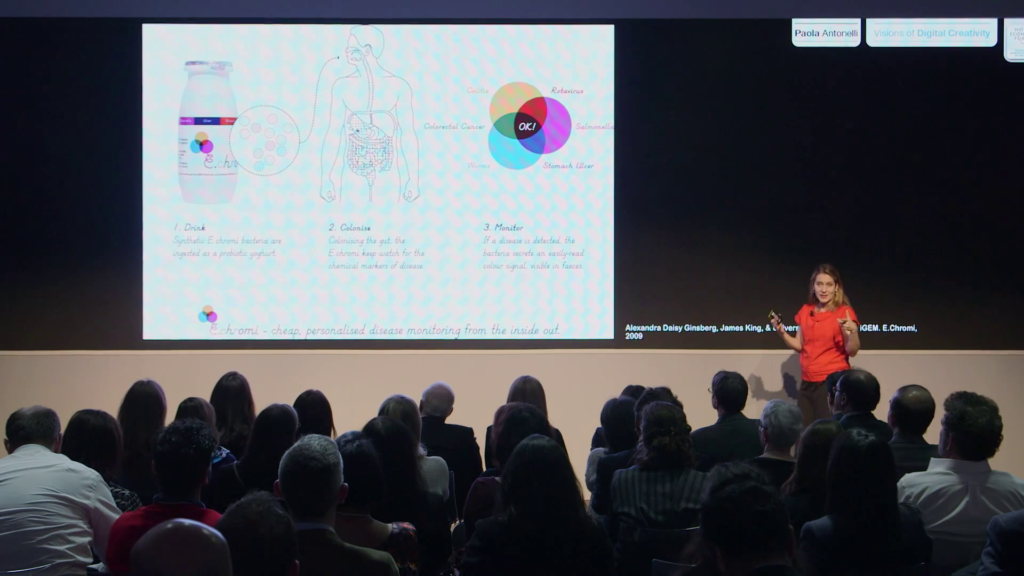

Alexandra Daisy Ginsberg, E. chromi: Living Colour from Bacteria

This is a project by Alexandra Daisy Ginsberg, the same person that did the new diagram. And it was a collaboration that happened during I think one of the first iGems. iGem is a competition that happens every year at MIT for students to do something with synthetic biology. In this particular case, Daisy had worked with the team from Cambridge, England to do this redesigned, re-engineered E. coli milkshake that would be drunk and then would change color depending on the enzymes released by different pathogens in your gut. So in other words, your stool was the diagnostic tool.

And it really could happen, and it did happen. They tested it. So, a scientist would not necessarily think up something like this, and thank god they use their time in a different way. But that’s when designers and artists come into play and really make things happen. So you see, synthetic biology— [audience laughter] Yeah, that was part of the presentation I was telling you—that would be the case. Synthetic biology, a collaboration— This is kind of a at a diagram of synthetic biology. They actually call them Lego—you know, synthetic bricks, and Andy, who’s a biologist at Stanford that kind of coined that term. And the iGem team’s here.

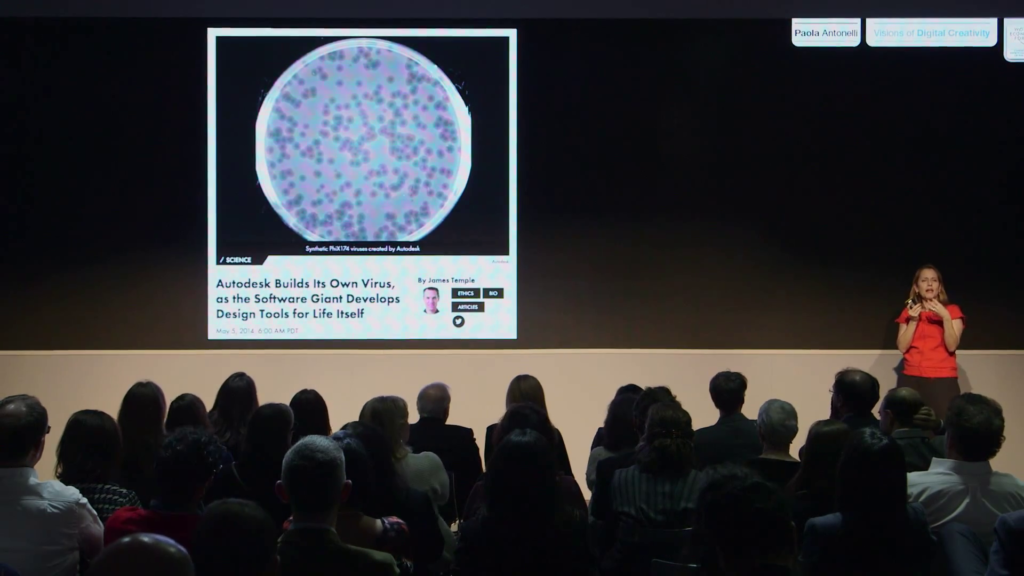

To the point that Autodesk has also designed a new virus. Andrew Hessel is their scientist in residence. So, synthetic biology is very serious, and right now I’m showing synthetic biology to you at this kind of rarefied level. But there are citizen scientist labs that are non-profit that are in all cities the also teach children how to work at this particular scale.

Of course, the visionaries go one step forward. Some are designing for the sixth extension and thinking up new organisms that can help us get rid of the carbon monoxide that we release. Others are making jewelry out of waste. Or we have Stewart Brand that is trying to de-extinct animals that don’t exist anymore.

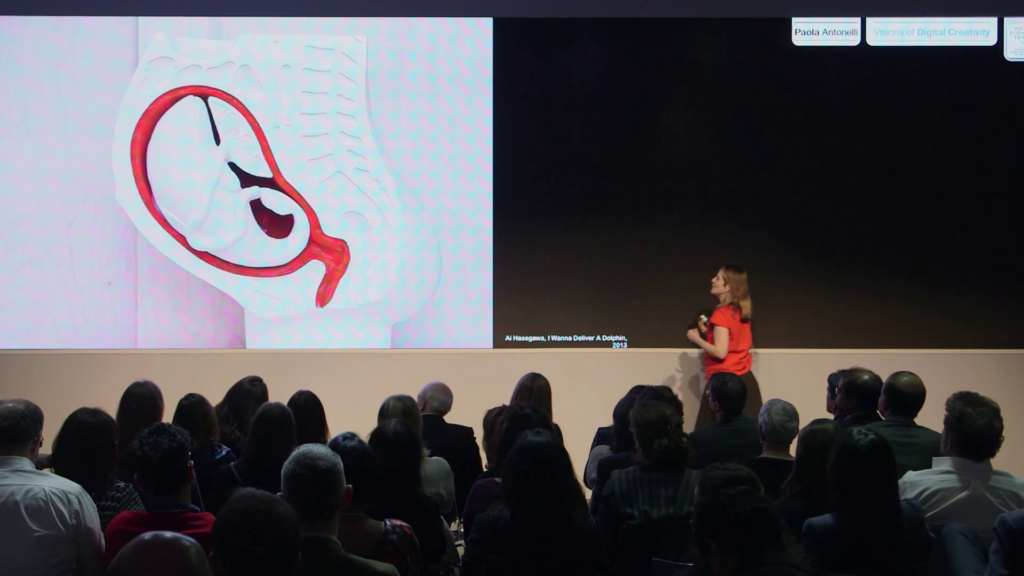

It really is far-fetched, what people do. And Steward Brand has also inspired this great designer from London, who decided to postulate a future in which women can gestate not human babies, but rather endangered species. And why not?

So, it’s all up for grabs. But the way we build is one of the biggest revolutions. I was telling you before about Joris Laarman and how he builds his chair using this particular software. There are other designers that are trying to create a new supply chain by having just made on time objects that are made of recycled. These chairs are made of recycled refrigerator interior. So, it really is a completely different way to think also of the supply chain in an organic way.

https://vimeo.com/55657102

Look at how, for instance, Joris Laarman is thinking also of making chairs in metals in the future. So you see here it’s a mixture of robotics, and instead an ancient sensibility for shapes that have existed for millennia. And that’s when I find the most interesting design happening. When it’s not about mimicking the future, but it’s building the future without forgetting the past. It’s quite an amazing way to build. This is metal slurry.

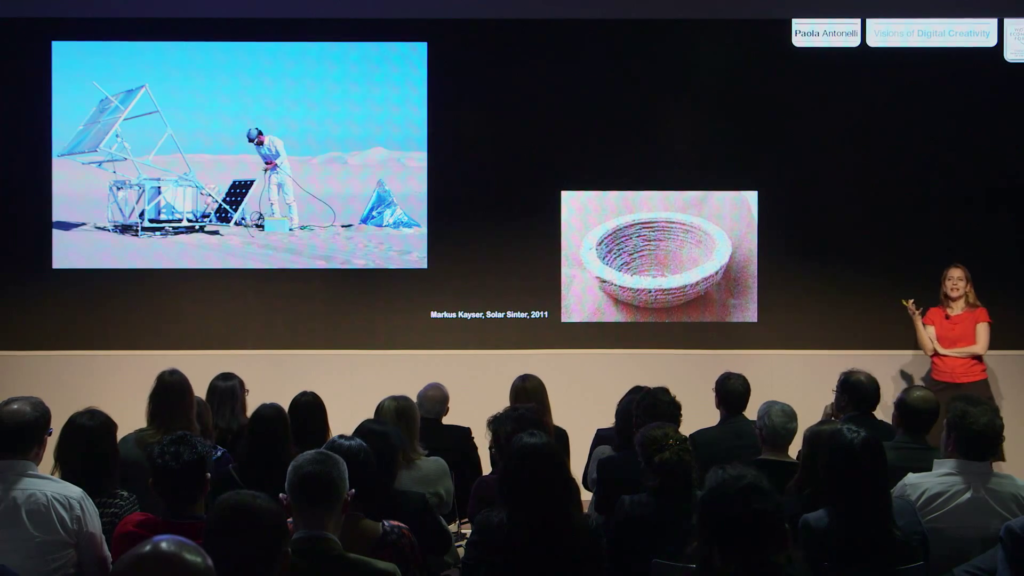

Markus Kayser, Solar Sinter [video documentation]

Other materials that are used very often are of course plastics and all the laser sintering materials. But Markus Kayser as you see here does 3D printing using the sand of the Sahara desert and the beams of the sun, which is quite wonderful. If you see the vessels that he makes, they look like they could have existed for millennia, but at the same time you see the horizontal marks of 3D printing. And it’s wonderful because it’s something ancient and contemporary at the same time. It’s something that could have never happened centuries ago, but that was happening already.

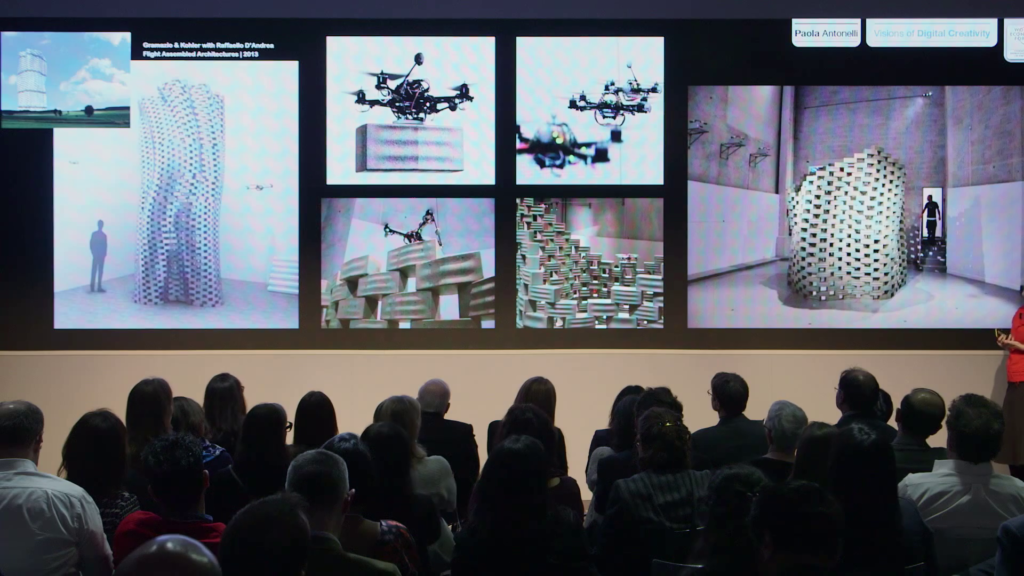

Ways to build from the ground up, ways to build harnessing collective intelligence or even swarm intelligence. You see here a very very Swiss and wonderful piece of architecture. It’s the collaboration between Gammazio & Kohler, two architects and Raffaello D’Andrea, who’s a robotic expert. And you see here that this building is built by robots. And the digital plan of the building is sent to their collective intelligence so that they can build it the way it’s needed to be built.

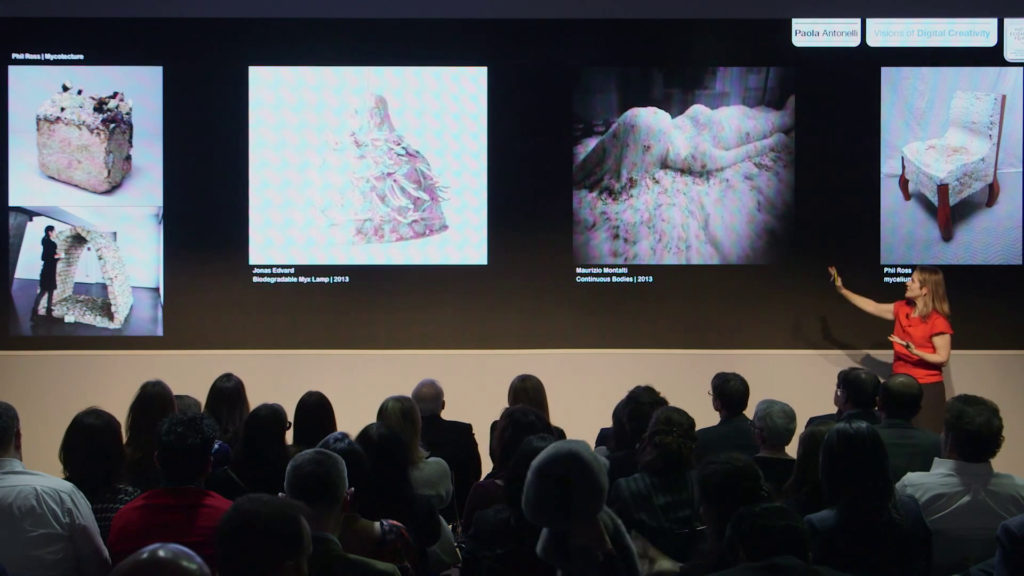

So it’s a completely different way in which we are approaching materials. This is more of the work of Neri Oxman that shows how 3D printing today can really mimic not only more organic shapes, but also more organic ways to build. You know, 3D printing has become really the stuff of everyday life for so many, but there are different ways and different sophistications, and this is one of the highest ways to mimic that kind of organic behavior.

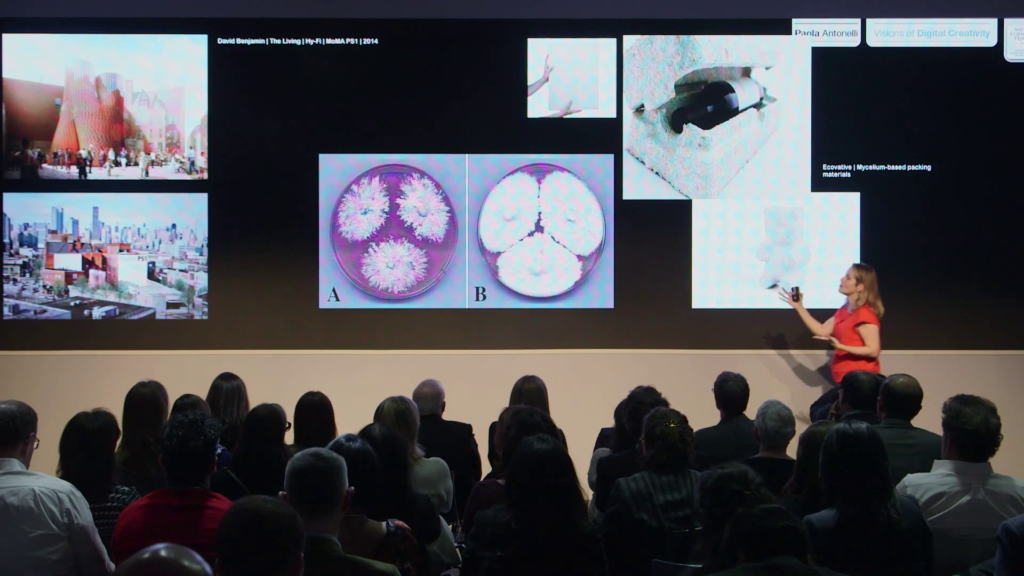

And I want to end by showing the amazing work of designers that are using mushrooms to build a lot of different structures from chairs, of course, to bricks and bridges, to even mortuary chambers. They are using the mycelium of mushrooms also to think of new ways to actually think of how we mourn and how we bury our loved ones.

And you see here applications of that kind of study. This is a structure that was built in Queens at MoMA PS1 last summer that was all made of bricks made of cornhusk that was kept together by mycelium of mushrooms. And you see the whole tower went up, and then it kind of biodegraded in a beautiful way, as if it were a sped-up decay of a city, of a little village in Tuscany. It was quite fantastic. And here you see instead the work of Ecovative, which is a company that has decided to use—actually they were among the first to experiment with this material—to have a substitute for polystyrene in packaging.

There are so many designers and architects and scientists that are working together, and that are using the intelligence of computers to insert different processes of nature in the way we build so that we will be able to get closer to nature in the way we will construct the future. Thank you very much.