Jeremy Keith: Hello everyone. Thank you for still being here. We’re on the final stretch now. I am here today to talk to you about the Web, and more specifically about web standards. [Audience member: “Yay!” Some general cheering.]

Ehh, here’s the thing. Here’s the thing about web standards. Web standards don’t exist. At least they don’t physically exist. They’re…intangible. But they’re in good company. Feelings are intangible but real. Hope. Despair. Ideas are intangible. Liberty. Justice. Socialism. Capitalism. The economy. Currency—all intangible. I’m sure we’ve all had those college thoughts, right. “Money isn’t real, man, it’s just bits of metal and paper; wake up, sheeple.”

Nations are intangible. Geographically, France is a tangible, physical place. But France the republic is an idea. And geographically North America’s a real, tangible physical landmass but ideas like “Canada” and “the United States” only exist in our minds. Faith the feeling is intangible. God the idea is intangible. Art the concept is intangible. A piece of art is instantiation of the intangible concept of what art is.

Incidentally I really like Brian Eno’s definition of what art is. He says art is anything we don’t have to do. We don’t have to make paintings, or sculptures, or films, or music. We have to clothe ourselves for practical reasons but we don’t have to make clothes beautiful. We have to prepare food to eat it, but we don’t have to make it a joyous event.

Also, by this definition, sports are also art. We don’t have to play football. Sports are also intangible. A game of football is an instantiation of the intangible idea of what football is. Football, chess, rugby, quidditch, and rollerball are all equally intangible. But football chess and rugby have a bit more consensus. Just like Christianity, Islam, Judaism, and the Force are equally intangible, but Christianity, Islam, and Judaism have a bit more consensus than the Force.

HTML is intangible. A web page is an instantiation of the intangible idea of what HTML is. But, we can document our shared consensus. A rule book for football is like a web standard specification; a documentation of consensus.

And by the way, economics, and religions, and sports, and laws…they’re all examples of intangibles that can’t be proven. Because they all rely on their own internal logic. There’s no outside data that can prove football, or Hinduism, or capitalism to be true. That’s very different to ideas like gravity, evolution, relativity, or germ theory. They’re all intangible, but provable. They’re discovered rather than create. They’re part of objective reality. Consensus reality is the collection of intangibles that we collectively agree to be true. Economy, religion, law, web standards.

Now we treat consensus reality much the same as we treat objective reality. In our minds, football, capitalism, and Christianity are just as real as buildings, trees, and stars. And sometimes consensus reality and objective reality get into fights. Some people have tried to make a consensus reality around the accuracy of astrology, or the efficacy of homeopathy, or ideas like the Earth being flat, 9/11 being an inside job, the moon landings never having happened. The Holocaust never having happened. Or vaccines causing autism. And these people are unfazed by objective reality, which disproves each one of these ideas.

It used to be that for a long time the consensus reality was that the sun revolved around the Earth. And Copernicus and Galileo demonstrated that the objective reality was that the Earth and all the other planets in our solar system revolve around the sun. Now after the dust settled on that particular punch-up, we switched up our consensus reality. We change the story. Because that’s another way of thinking about consensus reality. Our currencies, our religions, our sports, and our laws are stories that we collectively choose to believe.

And web standards are a collection of intangibles that we collectively agree to be true. They’re our stories. They’re our collective, consensus reality. They’re what web browsers agree to implement and what we agreed to use. The Web is agreement.

Now for human beings to collaborate together, they need a shared purpose. They must have a shared consensus reality, a shared story. And once a group of people share a purpose, they can work together to establish principles. Design principles are points of agreement. There are design principles underlying every human endeavor. And sometimes they’re tacit and sometimes they’re written down. And patterns emerge from the principles.

Here’s an example of a human endeavor, the creation of a nation-state like the United States of America. The purpose is agreed in the Declaration of Independence. The principles are documented in the Constitution. And the patterns emerge in the form of laws. HTML elements, CSS features, Javascript APIs are all patterns that we agree upon. And those patterns are informed by design principles.

I’ve been collecting design principles of varying quality at principles.adactio.com. And here’s one of the design principles behind HTML 5. It’s my personal favorite. It’s the priority of constituencies. “In case of conflict, consider users over authors over implementors over specifiers over theoretical purity.”

In case of conflict. That’s exactly what a good design principle does. It establishes the boundaries of agreement. If you disagree with the design principles of a project, there probably isn’t much point contributing to that project. Also, it’s reversible. You could imagine a different project that favored theoretical purity above all else. In fact, that’s pretty much what XHTML 2 was all about. XHTML 1 was simply HTML reformulated with the syntax of of XML. Lower case tags, lower case attributes, always quoting attribute values.

Remember, HTML doesn’t care whether tags are upper case and lower case or whether you put quotes around your attribute values—you can even leave out some closing tags. So, XHTML 1 was kind of a nice bit of agreement. Professional web developers agreed on using lower case tags and attributes, and we agreed to always quote our attributes. Browsers don’t care one way or the other.

But, XHTML 2 was going to take the error-handling model of XML and apply it to HTML. And this is the error-handling model of XML:

If the parser encounters a single error, don’t render the document. Of course nobody agreed to this. Browsers didn’t agree to implement XHTML 2. Developers didn’t agree to use it. It ceased to exist. Because it turns out that creating a format is relatively straightforward. But how do you turn something into a standard? The really hard part is getting agreement.

Sturgeon’s Law states that 90% of everything is crap. Coincidentally, 90 is also the percentage of the world’s crap that gets transported by ocean. Your clothes, your food, your furniture, your electronics. Chances are that at some point they were transported within an intermodal container. These shipping containers are probably the most visible, and certainly of the most important, standards in the physical world. Before the use of intermodal containers, loading and unloading cargo ships was a long, laborious, and dangerous task.

Along came Malcolm McLean, who realized that the whole process could be made an order of magnitude more efficient if the cargo were stored in containers that could be moved from ship, to truck, to train. But he wasn’t the only one. The movement towards containerization was already happening independently around the world. But everyone was using different-sized containers, with different kinds of fittings. And if this continued, the result would be a Tower of Babel instead of a smoothly-running global logistics chain.

Malcolm McLean and his engineer Keith Tantlinger designed two crate sizes, twenty-foot and forty-foot, that would work for ships and trucks and trains. Their design also incorporated an ingenious twist lock mechanism to secure containers together. But the extra step that would ensure that their design would win out was this: Tantlinger convinced McLean to give up the patent rights.

Now this wasn’t done out of hippy-dippy ideology. These were hard-nosed businessmen. But they understood that a rising tide raises all boats, and they wanted all boats to be carrying the same kind of containers. And without the threat of a patent lurking beneath the surface ready to torpedo the potential benefits, the intermodal container went on to change the world economy (the world economy being very large and intangible).

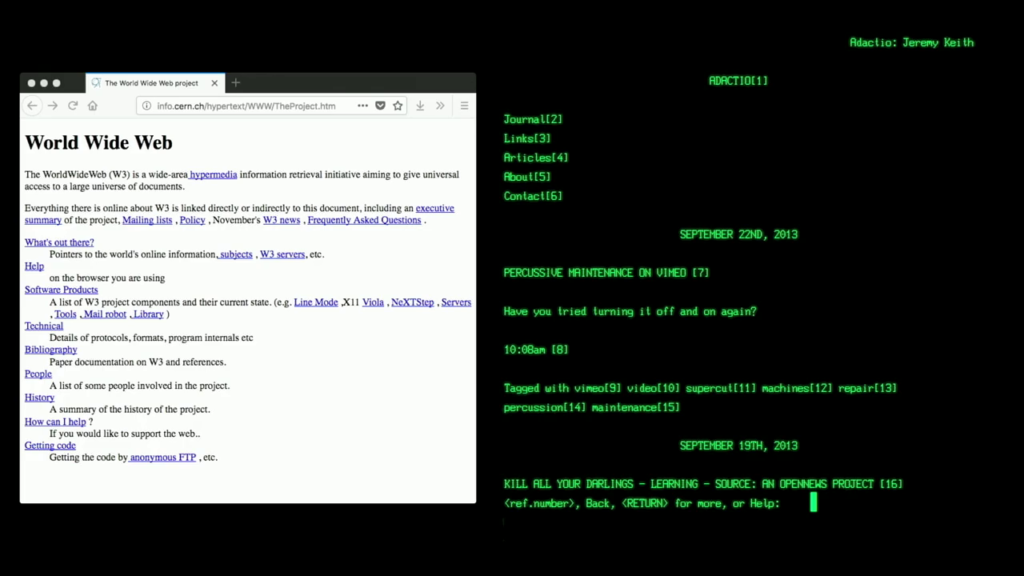

The World Wide Web also ended up changing the world economy and much more besides. And like the intermodal container, the World Wide Web is patent-free. Again, this was a pragmatic choice to help foster adoption. When Tim Berners-Lee and his colleague Robert Cailliau were trying to get people to use their World Wide Web project, they faced some stiff competition. Lots of people were already using Gopher. Anyone remember Gopher? Wow. And the seemingly unstoppable growth of Gopher was somewhat hobbled in the early 90s when the University of Minnesota announced it was going to start charging fees for using it. And this was a cautionary lesson for Berners-Lee and Cailliau. They wanted to make sure that CERN didn’t make the same mistakes. So, April 30th, 1993, the code for the World Wide Web project was made freely available. This was for everyone.

If you’re trying to get people to adopt a standard or use a new hypertext system, the biggest obstacle you’re going to face is inertia. As the brilliant computer scientist Grace Hopper used to say, “The most dangerous phrase in the English language is ‘we’ve always done it this way.’ ” Now Rear Admiral Grace Hopper waged war on business as usual. She was well aware how arbitrary business as usual is. Business as usual is simply the current state of our consensus reality. She said, “Humans are allergic to change. I try to fight that. That’s why I have a clock on my wall that runs counter-clockwise.”

But think about it. Our clocks are a perfect example of ubiquitous but arbitrary convention. Why should clocks run clockwise and not counter-clockwise? Well one neat explanation is that clocks are mimicking the movement of shadow across the face of a sundial. In the Northern Hemisphere. And had clocks been invented in the Southern Hemisphere, they would indeed run counter-clockwise. But on a clock face itself, why do we carve up time into twenty-four hours. Why are there sixty minutes in an hour? Why are there sixty seconds in a minute?

Well, it probably all goes back to Babylonian accountants. Early cuneiform tablets show that the used a sexagesimal system for counting. It was because base 60…sixty is the lowest number that can evenly divided by six, five, four, three, two, and one. But we don’t count in base 60. We count in base 10. I mean that in itself is arbitrary, we just happen to have a total of ten digits on our hands.

So, if the sexagesimal system of telling time is an accident of accounting, and base 10 is more widespread, why don’t we switch to a decimal time-keeping system? It has been tried. The French Revolution introduced not just a new decimal calendar much neater than our base 12 calendar, but also decimal time. Each day had ten hours. Each hour had one hundred minutes. And each minute had one hundred seconds. So much better. It didn’t take. Humans are allergic to change. And sexagesimal time may be arbitrary and messy but…we’ve always done it that way.

It’s also why I’m not holding my breath in anticipation of the USA ever switching to the metric system. Instead of trying to completely change people’s behavior, you’re likely to have more success by incrementally and subtly altering what people are used to. And that was certainly the case with the World Wide Web. The hypertext transfer protocol sits on top of the existing TCP/IP stack. The key building block of the web is the URL. But instead of creating an entirely new addressing scheme the Web uses the existing Domain Name System.

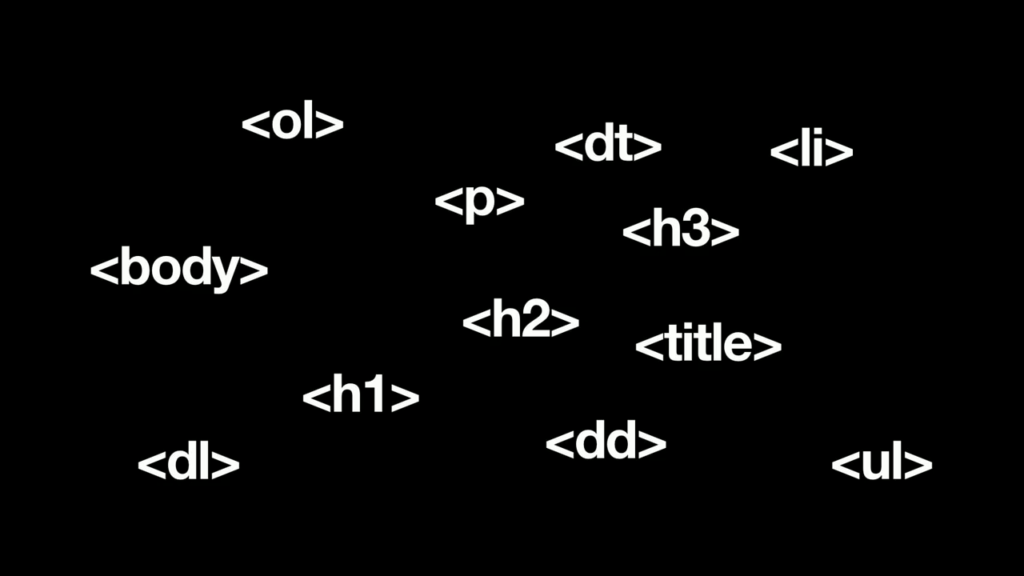

Then there’s the lingua franca of the Web. And these elements probably look pretty familiar to you, right? You recognize this language, right? Right.

It’s SGML. Standard Generalized Markup Language. Specifically, it’s CERN SGML, a flavor of SGML that was already popular at CERN when Tim Berners-Lee was working on his World Wide Web project. And he used this vocabulary as a basis for the Hypertext Markup Language. And because this vocabulary was already familiar to people at CERN, convincing them to use HTML wasn’t that much of a hard sell. They could take an existing SGML document, change the file extension to “.htm”, and it would work in one of those new-fangled web browsers.

In fact HTML worked better than expected. The initial idea was that HTML pages would be little more than indices that pointed to other files containing the real meat and potatoes of content. You know, spreadsheets and word processing documents, whatever. But to everyone’s surprise, people started writing and publishing content in HTML. And was HTML the best format? Far from it. But it was just good enough, and easy enough, to get the job done.

And it has since changed. But that change has happened according to another design principle: evolution not revolution. From its humble beginnings with a handful of elements borrowed from CERN SGML, HTML has grown to encompass an additional 100 elements over its lifespan. And yet it’s technically the same format. And this is a classic example of the paradox called the Ship of Theseus, better known in this country as Trigger’s Broom.

You can take an HTML document written over two decades ago and open it in a browser today. Even more astonishing, you can take an HTML document written today and open it in a browser from two decades ago. And that’s because the error-handling model of HTML has always been to simply ignore any tags it doesn’t recognize and render the content inside them. And that pattern of behavior is a direct result of the design principle “degrade gracefully.”

Document conformance requirements should be designed so that Web content can degrade gracefully in older or less capable user agents, even when making use of new elements, attributes, APIs and content models.

HTML Design Principles

Here’s a picture from 2006. That’s me in the cowboy hat.

This picture was taken in Austin, Texas. It’s an impromptu gathering of people involved in the microformats community. And microformats, like any other standards, are sets of agreements. In this case their agreements on which class values to use to mark up some of the missing elements from HTML: people, places, events, that’s pretty much it. And yes, they do have design principles, some very good ones. But that’s not why I’m showing this picture.

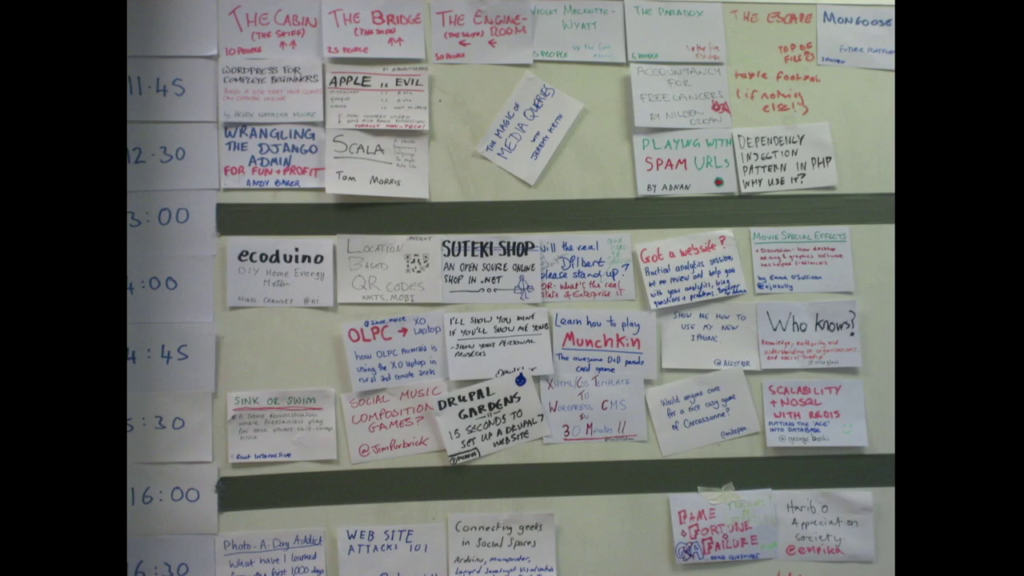

Some of the people in this picture Tantek Çelik, Ryan King, and Chris Messina were involved in the creation of BarCamp, a series of grassroots geek gatherings.

And barcamps sound like they shouldn’t work but they do. The schedule for the event is arrived at collectively at the beginning of the gathering. It’s kind of amazing how the agreement emerges; rough consensus and running events. And in the run-up to a barcamp in 2007, Chris Messina posted this to the fledgling social networking site twitter.com:

https://twitter.com/chrismessina/status/223115412

This was when tagging was all the rage, right. We were all about folksonomies back then. And Chris proposed that we would call this a hashtag.

Thinking that hashtags disrupt the reading flow of natural language. Sorry @factoryjoe.

— Jeremy Keith (@adactio) November 6, 2007

Now I wasn’t a fan. But it didn’t matter what I thought. People agreed to this convention. And after a while, Twitter began turning the hashtagged words into links. And in doing so, they were following another HTML design principle: pave the cowpaths. Which sounds like advice for agrarian architects, but it is further clarified:

When a practice is already widespread among authors, consider adopting it rather forbidding it or inventing something new.

HTML Design Principles

Now Twitter had previously paved a cowpath when people started prefacing user names with the operand symbol. That convention didn’t come from Twitter, but they didn’t try to stop it. They rolled with it and turned any username prefaced within an at symbol into a link.

And the at symbol made sense because people were used to it from email. And the choice to use that symbol in email addresses was made by Roy Tomlinson. He needed a symbol to separate the person and the domain. He looked down at his keyboard. He saw the at symbol. And he thought, “That’ll do.” And perhaps Chris followed a similar process when he proposed the symbol for the hashtag. It could’ve just as easily been called a number tag, or an octothorpe tag, or a pound tag. And this symbol started life as a shortcut for pound. Or more specifically “libra pondo,” meaning a pound in weight.

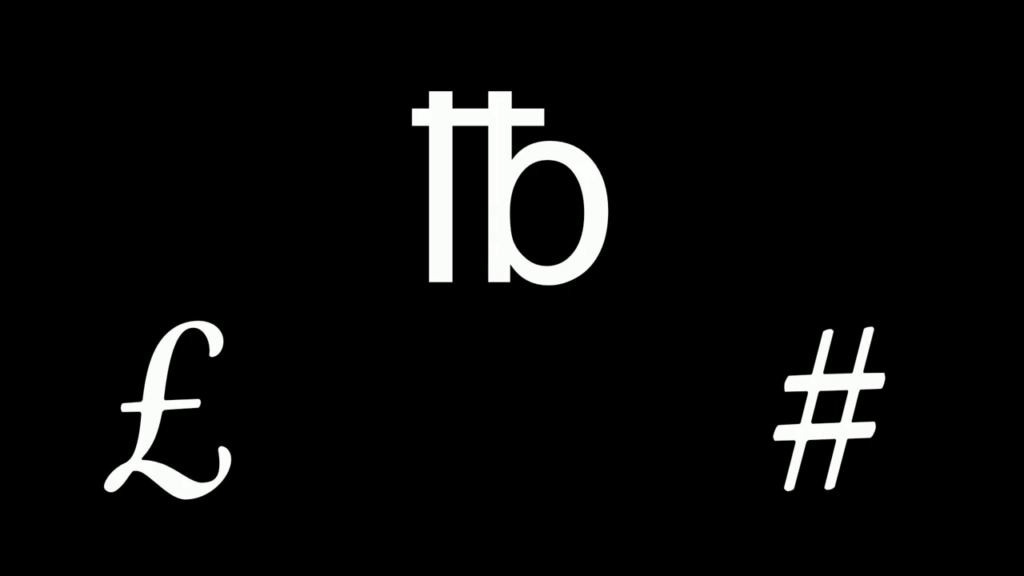

And libra pondo was abbreviated to “lb” when written. And that got turned into a ligature when written hastily. And that shape was the common ancestor of two symbols we use today: pound, and pound.

And the eight-pointed symbol was perhaps jokingly renamed the octothorpe in the 60s when it was added to telephone keypads. And it’s still there on the digital keypad of your mobile phone. And if you were to ask someone born in this millennium what that key is called, they would probably tell you it’s the hashtag key.

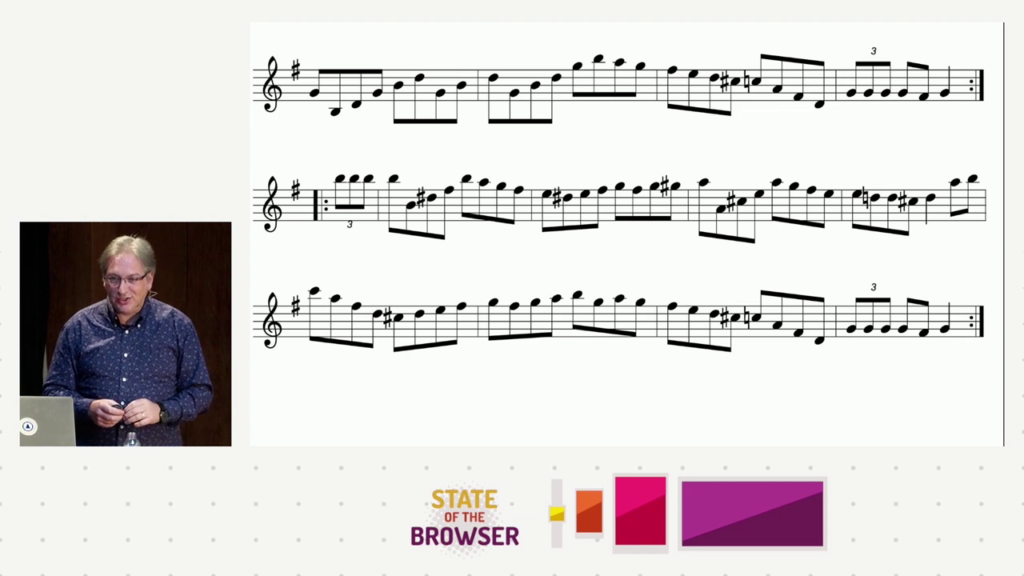

And if they’re learning to read sheet music, I’ve heard tell that they refer to the sharp notes as the hashtag notes. And if this upsets you, you’re probably the kind of person who rages at the word “literally” being used to mean figuratively. Or supermarkets with aisles for ten items or less instead of ten items or fewer.

Well tough luck. Because the English language…is agreement. And that’s why English dictionaries exist not to dictate usage of the language but to document usage. And it’s much the same with web standards. They don’t carve the standards into tablets of stone and then come down the mountain to distribute them amongst the browsers. No, it’s what the browsers implement that gets carved in stone. That’s why it’s so important that browsers are in agreement. In the bad old days of the Browser Wars of late 90s we saw what happened when browsers implemented their own proprietary features. Standards require interoperability. Interoperability requires agreement.

Alright, so what can we learn from the history of standardization? Well there are some directs lessons from the HTML Design Principles like the priority of constituencies. Listen. I want developer convenience as much as the next developer, but never at the expense of user needs. And I’ve often said that if I had the choice between making something my problem and making it the user’s problem, I’ll make it my problem every time. That’s the job. And I worry that these days developer convenience is sometimes prized more highly than user needs. I think we could all use a priority of constituencies on every project we work on. And I would hope that we would prioritize users over authors.

Degrade gracefully. I know. I go on and on about progressive enhancement a lot. Sometimes I make it sound like a silver bullet. And it kinda is. I mean, you can’t just buy a bullet made of silver. You have to make it yourself. And if you’re not used to crafting bullets from silver it will take some getting used to. Again, if developer convenience is your priority silver bullets are hard to justify. But, if you’re prioritizing users over authors, progressive enhancement is the logical methodology to use. And it’s a testament to the power and flexibility of the Web that we don’t have to build with progressive enhancement. We don’t have to build with a separation of concerns like structure and presentation and behavior. We don’t have to use what the browser gives us: buttons, dropdowns, hyperlinks. If we want, we can make those things from scratch using Javascript, divs, and some ARIA attributes.

But why do that? Is it because those native buttons and dropdowns might be inconsistent from browser to browser? Consistency is not the purpose of the Web. Universality is the key principle underlying the Web. And our patterns should reflect the intent of the medium. Use what the browser gives you. Build on top of those agreements. Because that’s the bigger lesson to be learned from the history of web standards, and clocks, and containers, and hashtags. Our world is made up of incremental improvements to what has come before. And that’s how we will push forward to a better tomorrow. By building on top of what we already have, instead of trying to create something entirely from scratch. And, by working together to get agreement instead of going it alone.

The future can be a frightening prospect. And I often get people asking me for advice on how they should prepare for the Web’s future. And usually they’re thinking about which programming language or framework or library they should be investing in. But those specific patterns matter much less than the broader principles of working together, collaborating, and coming to agreement. And it’s kind of insulting that we refer to these as soft skills. They couldn’t be more important.

And working on the Web…you know, it’s easy to get downhearted by the seemingly ephemeral nature of what we build. None of it is…real. None of it is…tangible. And yet, looking at the history of civilization, it’s the intangibles that survive. Ideas, philosophies, cultures, and concepts. And the future can be frightening because it is intangible and unknown. But, like all the intangible pieces of our consensus reality, the future is something we collectively construct through agreement. Now let’s agree to go forward together and build the future Web. Thank you.