Introducer: It’s my pleasure to introduce our Digital Dialogues speaker today. Alex Wright is the Director of Research at Etsy and former Director of User Experience and Product Research for the New York Times. He’s also Professor of Interaction Design at the School of Visual Arts, and the author most recently of Cataloging the World: Paul Otlet and the Birth of the Information Age from Oxford University Press this year 2014.

He’s previously led interaction design and research projects for IBM, Yahoo!, the Long Now Foundation, and the California Digital Library, among others. His writing has appeared in the New York Times, The Atlantic, Wilson Quarterly, The Believer, Harvard Magazine, among others. And I learned this morning that he is the author of the first Harvard Libraries web page, among many accomplishments that are interesting. Thank you for joining us.

Alex Wright: The less said about that web site, the better. Thanks for having me. Thanks for making all the arrangements, it’s great to be here. And thanks to all of you for coming.

I was going to talk a little bit today about Paul Otlet. I wrote this book about him. I thought I would share a little bit. Whenever I give this talk I always ask (I’m always curious what the response will be today.) before today who had ever heard of Paul Otlet? That’s two more people than usually ever say yes to that question. Basically very few people have heard of Paul Otlet.

The elevator pitch for Paul Otlet is he is this Belgian guy who invented something like the Internet in the 1930s and was then promptly forgotten after World War II. That’s how I got interested in him. I’ve been interested for several years in the pre-history of hypertext and looking at systems that came before the Web and seeing if there—just in search of certain interesting ideas that were left by the wayside, and looking at how other people were thinking about the possibilities of networked information spaces before the Web. And that’s what sort of led me to Otlet. Certainly the reason that there’s any interest in him today I think largely has to do with these ideas he had about a global network that he imagined long before there were computers or modern networking protocols.

I’ll talk about that in a little bit, but as I got into the process of researching more and more about him I found out there’s really a lot more to him than that, and I wanted to give you a little bit of perspective on Otlet’s broader vision, which I think is in a way even more interesting as a reference point for thinking about some of the changes we’re seeing today as our lives are increasingly reshaped by technology and networks. What Otlet offers is a different way into that space, and a different way of thinking about what a networked world could look like. I’d like to just give you a few glimpses of some of his ideas.

Also I think the reason Otlet’s interesting is he gives us a window into a period of time that’s not really studied all that often. There’s sort of a conventional history of computer science that looks at the contributions of people like Charles Babbage, and Alan Turing, and some of the names that people tend to recognize. But I feel like there’s sort of an alternative lineage of thought that is largely overlooked, that has a lot to do with the way the era of networks and computers has taken shape. I think a lot of that has to do with this early period in the late 19th and early 20th centuries when we start to see the beginnings of a contemporary information explosion, people starting to work with that problem, and a lot of those people are coming out of the library science world. I think that perspective has been largely overlooked in the conventional history of computer science. So I wanted to use this as an opportunity to expose you to some of the interesting ideas that I think deserve a little more consideration.

Otlet’s dream was to create this universal repository of all the world’s knowledge. He spent the better part of five decades really pursuing that vision and it evolved over time. But what he really tried to accomplish was something fairly ambitious and all-encompassing, and of course he failed. Nobody’s ever really succeeded in doing that, but he wasn’t the first person to try to do such a thing. Certainly there have been, throughout the history of recorded information, there have been people who have tried at various times to create some sort of comprehensive repository. The example that often gets evoked is the Library of Alexandria, of course, but there have been many other attempts. You can go further back to ancient Sumeria. You can look at the Vatican library in the Middle Ages. The Chinese Emperor Shi Huangdi tried to do something like this. Lots of people have tried to create the all-encompassing library.

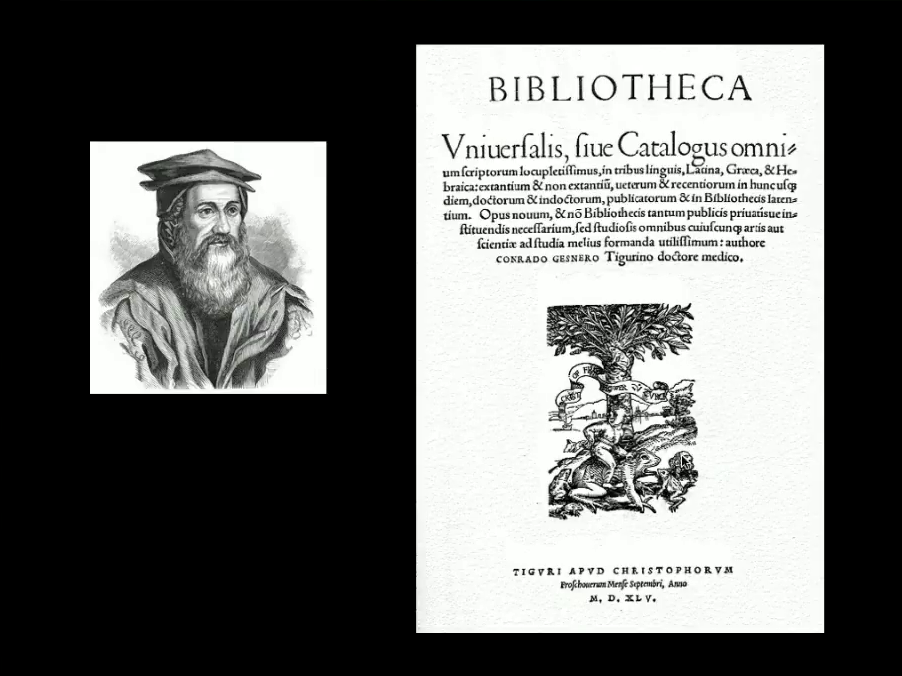

But one particular precursor I think is interesting is a guy named Conrad Gessner. He was a Swiss naturalist who worked in the 16th century to try to create what he called the Universal Bibliography of all of the world’s published knowledge. And I think Gessner’s probably the most direct intellectual ancestor of Otlet. He had developed this indexing technique through his work with biology. He had basically tried to create a system for cataloging all of the world’s plants and animals. The way that he did that was he developed a technique of writing things down on little slips of paper and then taking those slips of paper and indexing and organizing them. He realized over time that the same technique could be used for other things as well.

So he got it into his head that he could perhaps start to use this method of using little slips of paper to collect bibliographical information. So he started to create what were really sort of prototype library index cards. He began this process of trying to inventory everything that had ever been published, and then he published it a a book called the Bibliotheca Universalis.

As far as I know he was the first person to come up with that idea. It’s a simple idea, just cut up little slips of paper and write things down and then file them. But as far as I’ve been able to determine he was the one who came up with that idea. And the idea really started to take on a life of its own after Gessner. He sort of popularized that approach and in the centuries that followed, other people picked up on the idea, one of whom was the philosopher Leibniz, who took that idea a step further.

Leibniz was an obsessive note-taker. Basically any time a thought popped into his head, or he read something interesting in a book, or had an interesting conversation with somebody, he would take notes just incredibly rigorously. He would write everything down, and he used Gessner’s technique of writing everything down on little slips of paper.

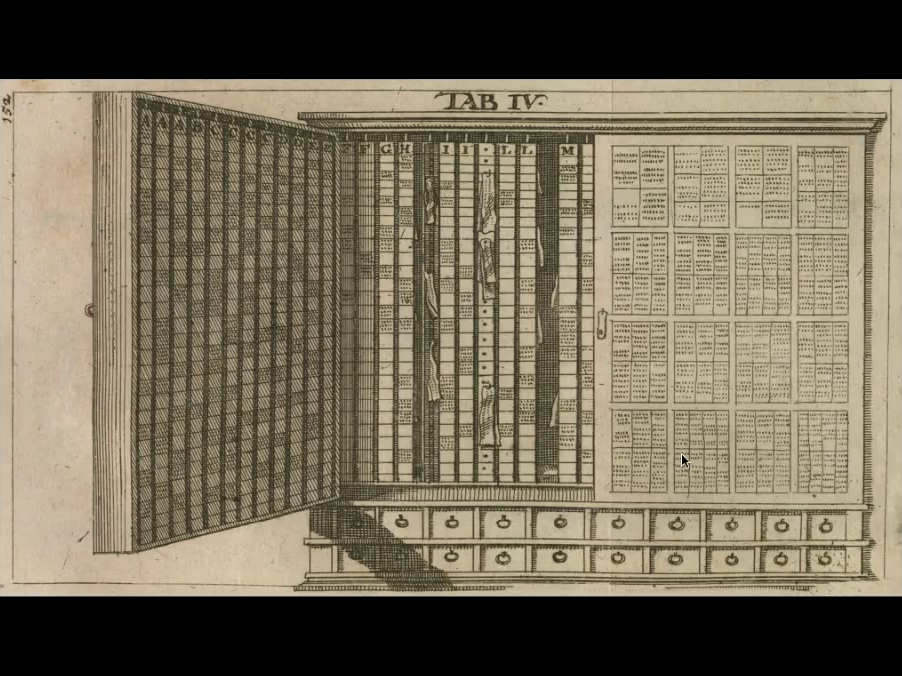

He then developed this cabinet. It looks like this Rube Goldberg machine, but it’s basically a filing system where he would take all these slips of paper and file them into this very precise cataloging scheme that he would then use to retrieve information when he wanted it when he was writing a new piece, an essay, or a book. He would use this as his kind of information storage device.

Other people in the years that followed also came up with variations on this sort of thing, sometimes called a memory cabinet, and as years went by librarians started getting interested in this possibility of creating physical tools for storing and cataloging information. Up until this time most library catalogs had really looked like the book that Gessner produced. They were essentially books with inventories of titles and authors and things on them. But Gessner’s innovation led some librarians—including there’s a guy who’s the librarian in Switzerland—to come up with some different ideas about how you could apply this technique of using index cards.

The idea that emerged was to try to create something a little more durable and a little more standardized. So what they came up with was this notion of using playing cards, which at the time were widely used— Back in the day, playing cards were printed on one side, so they were blank on the other side, and cards were used frequently for all kinds of other purposes, like note cards, business cards, people would just use them as kind of scrap paper. But they had several advantages. One, they were fairly durable; they were thicker paper stock. And they were a standard sized. So with index cards you could basically put them in a drawer and they lent themselves to being flipped through in kind of a random-access way.

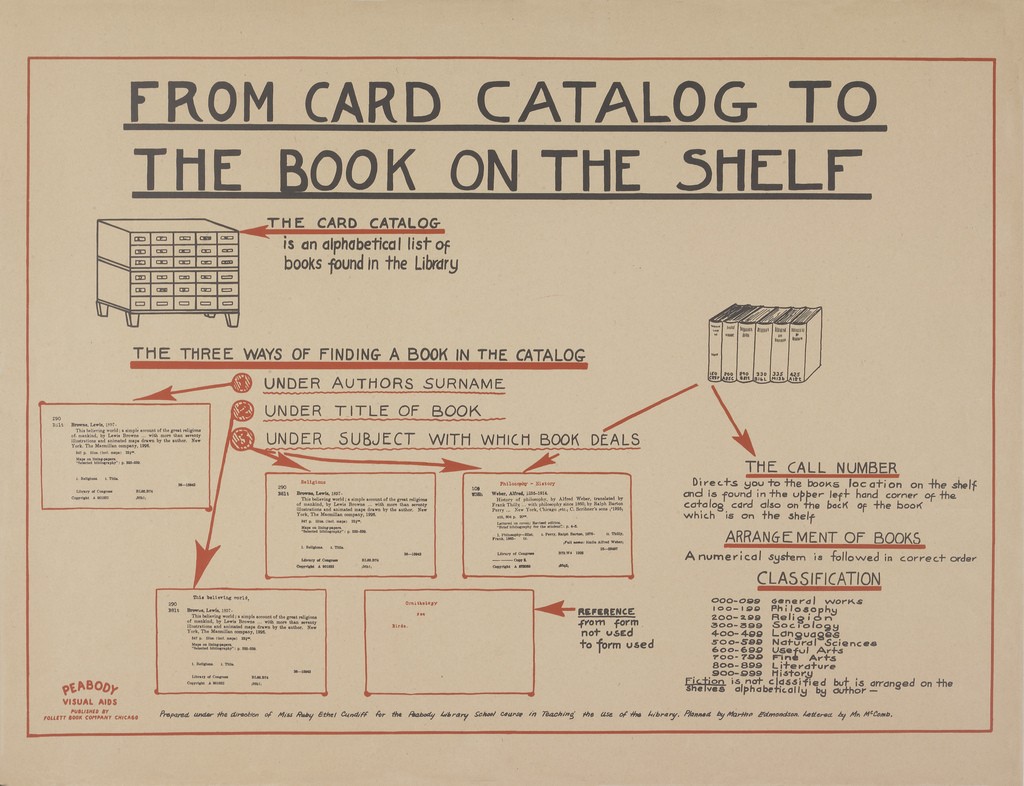

This basically became the genesis of the modern library card catalog that most of us grew up with, a set of drawers with cardboard cards that you could flip through. The origin of that was in playing cards.

So this whole stream of thought was developing over the course of a couple of hundred years, taking us up into the 19th century. But there were really very few libraries that needed anything like this. Most library collections were still pretty small except for the great national libraries, or the major university libraries. There really were not a whole lot of libraries of any significant size that required any kind of system like this.

But that started to change in the 19th century, and the reason for that was industrialization. As the Industrial Revolution started to gather steam, so to speak, in the 19th century, you started to see a couple of things happen. One was the industrialization of the printing press itself. You started to see the early steam-powered printing presses that were able to produce information more rapidly than the old corkscrew presses that dated back to Gutenberg. And at the same time there’s innovations in the production of paper. They started to create rag paper, which is much cheaper and more affordable.

Getting into the latter half of the 19th century, you started to see a more educated populace. You started to see workers moving to cities, receiving public education, becoming literate. So there was a growing demand. The supply was getting cheaper: steam-powered printing, cheap rag paper, and the demand was increasing with more and more people being able to read.

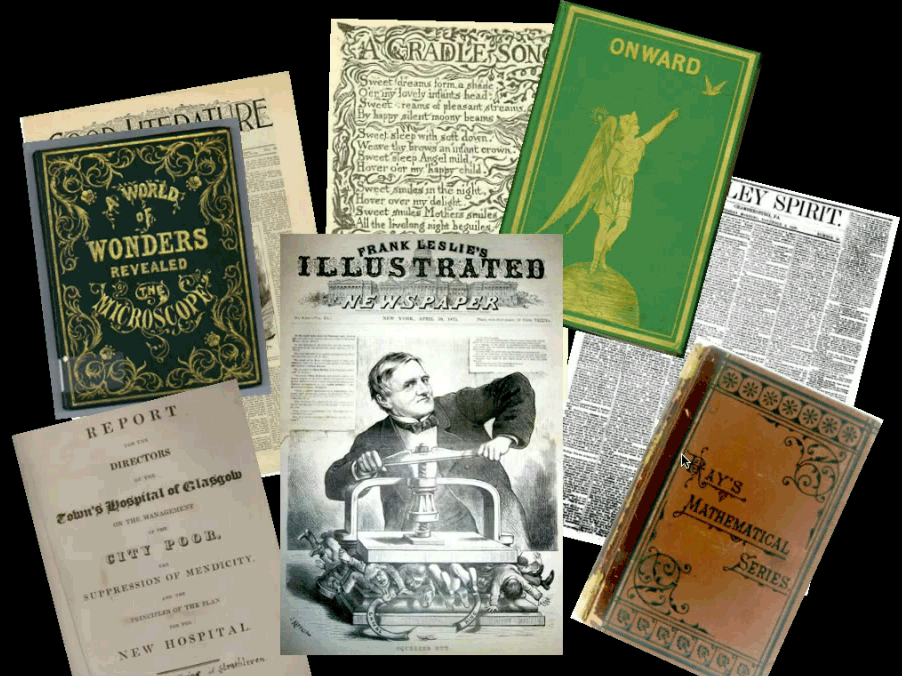

This started to really fuel the explosion of popular reading material in the 19th century. This was the era of Dickens, the first penny dreadfuls, the first popular daily newspapers started to happen. There was suddenly this incredible proliferation of written material coming out. And increasingly people were starting to struggle with what to do with all this information and how to archive it, how to store it. That job increasingly fell to librarians, and library collections were growing rapidly. Now it was not just the big research library collections, but by the late 19th century you started to see public libraries, you also started to see even within organizations like companies and government bureaus, were all creating this flood of printed information that people were trying to figure out what to do with.

Image via Char Booth, Flickr

It was during this time that people like Melvil Dewery came along, and a contemporary of Dewey’s Charles Cutter started to develop more elaborate cataloging systems to deal with this overflow of information. The idea was to create more scalable systems. So previously most libraries had come up with their own cataloging schemes that were fairly bespoke and custom, but what Dewey wanted to do was to create a system that could be scaled across the entire spectrum of public libraries and other libraries in the US. He started to create a much more industrial-scale system for doing that, so that there were clearly-delineated rules, standardized practices, everything was meant to be a kind of modular system that could be used in different contexts and he thought would create great efficiency. It was a very industrial kind of idea of creating operational efficiency in the way that information was managed.

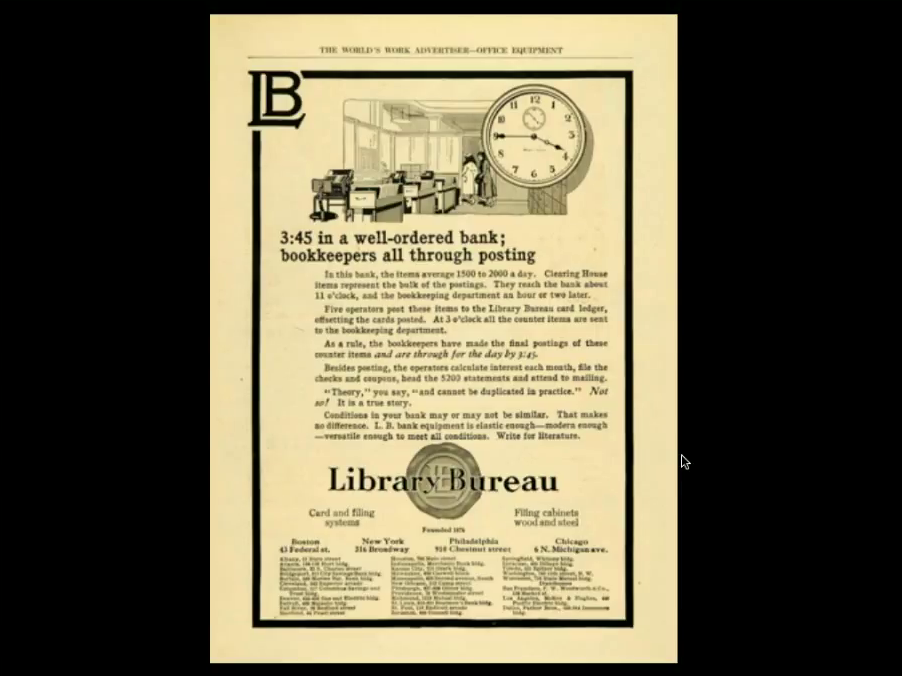

Even though he’s sort of known as this innovator in the library world, Dewey was also very interested in applications of these systems in business as well. So he created a company called The Library Bureau that took a lot of these tools that he was developing like card cataloging systems and actually got into creating other kinds of business equipment as well, and started to market it to corporations. He eventually created this company called The Library Bureau that started to create these filing systems that could then be used in all different kinds of organizations. When you think about it, what he was developing was a kind of flat-file database system that you could use to archive your company records, your annual reports, whatever kinds of paper you might be producing. He eventually ended up entering into a partnership with another company that was started by the family of Herman Hollerith, which eventually became IBM, and eventually they converged. The beginnings of IBM you can directly trace to the heritage of the Library Bureau and card catalogs. So this early flat-file database system became very much a core part of IBM’s offering going forward, so there’s kind of an interesting direct connection there between the history of the library world and the eventual rise of one of the major high-tech companies of the 20th century.

So this whole stream of development was happening with the creation of these increasingly scalable, ordered, structured systems for organizing information that was being fed by this vast outpouring of information. At the same time, another couple of interesting developments were happening.

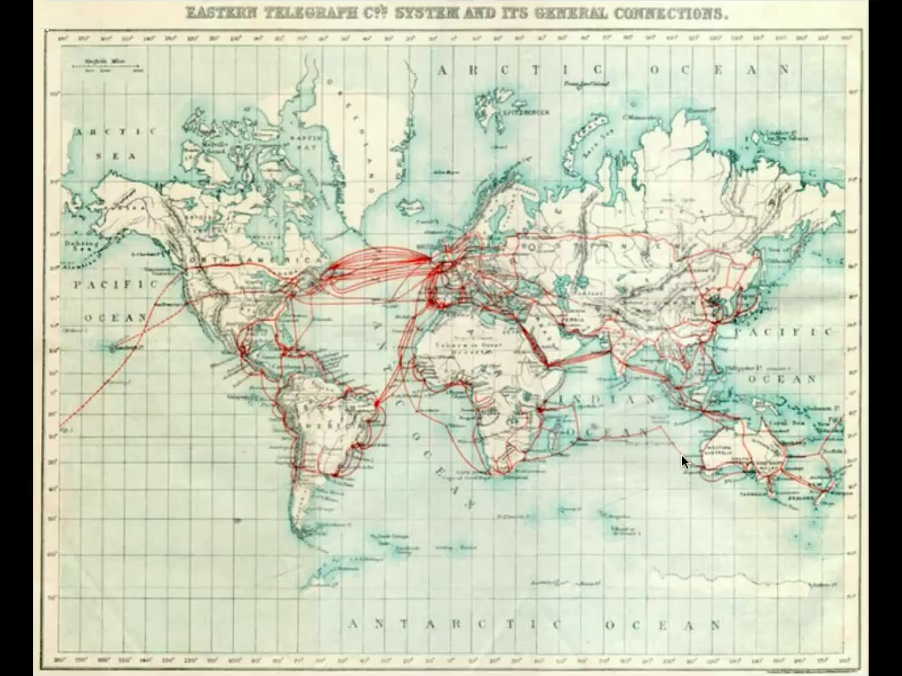

One was the spread of networks. This is a map of the telegraph network sometime in the late 19th century. After the initial spread of the telegraph in the US, it quickly started to spread all over the world, and you started to see these networks emerge that allowed for people to transmit coded messages great distances relatively instantaneously. At the same time, other kinds of networks were also starting to spread. So in addition to telegraph networks, railroads were taking off, the postal system was starting to become internationalized and this was kind of a new thing in the 19th century. It was actually not easy to send a letter from one country to another until the mid- to late-19th century. Governments started entering into agreements to standardize communication and commerce and create frameworks for increasing the flow of information across national borders.

So the topology of networks started to take shape, it started to really shape the way information flowed across national boundaries which, coupled with the increasing proliferation of written information, let to this growing exchange of written information across countries. And as a result, scholars, political activists, other kinds of researchers, government bureaucrats, started to enter into associations with each other in a new way. We started to see the rise of international associations, which there had been very few of before the mid-19th century.

You started to see this rising tide of internationalism influencing a whole bunch of domains of inquiry, a lot of scientific societies started to create international bodies, international standards bodies started to emerge. So there’s this growing feeling of connectedness, that information was flowing, people are able to communicate across borders, and it was in that milieu that people start to think about the idea of a more internationalized, more connected world.

In terms of people’s day-to-day experiences, those networks were starting to affect the way people lived their lives. In Paris there was this thing called the théâtrophone, which was basically a device that let you listen to live broadcasts of the opera. You could have one in your home, Proust had one of these in his house, a lot of hotels had them. So you could get these kind of live-streaming audio broadcasts.

In Hungary, there was something called the Telefon-Hirmondo. It was basically a daily audio newspaper, and they hired a guy who had a particularly deep baritone voice which you could hear over the tinny receivers to read. It was like a daily newscast that would go out and be piped into banks and hotels and things. So it was before radio, but at the time it was a way of having this kind of shared experience delivered over a network so people could consume news in sort of real-time.

In Paris, there was a network of thousands of miles of pneumatic tubes that ran under the streets that allowed people to send written notes to each other in relatively real-time. This was essentially like a giant packet switching network. My friend Molly Steenson does a great presentation on this. It was all managed by the postal service. So you would send your message through the pneumatic tube, it would go to a kind of [grabbing?] station, and the it would get send to its final destination.

I just wanted to present all this as kind of context for Paul Otlet. I think it’s important to understand the world that he was coming into, and how things were changing, and how in this world he was able to begin to think about the problem of organizing information in a new way.

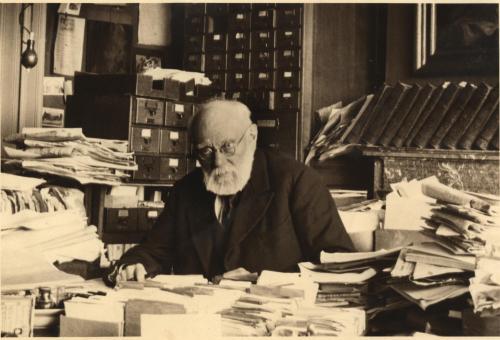

This is Paul Otlet as a young man. Just a very brief biographical sketch. He was born to a fairly well-to-do bourgeois Brussels family. His mother died when he was very young, and his father was an industrialist who traveled the world selling tram systems to different countries. He was going all over the world, installing and selling these city transit systems. His family owned a private island in the Mediterranean, and Otlet was basically raised by tutors. His father actually didn’t believe in school. He didn’t want to send his boys to public school. He thought they would just be corrupted by that. He wanted them to be raised in a very idealized world. So they had private tutors for most of his childhood, and led a very interesting, unusual life. He and his brother were very into collecting natural specimens. They created their own museum when they were children, the Musée Otlet. He was a very bookish young man. So they spent a lot of time immersed in books and encyclopedias and very self-directed education.

Until he was about 13 or 14, when he was sent off to Jesuit school and had a very hard time there. He was very introverted, very bookish, and spent most of his time holed up in the library. So much so that eventually the Jesuit fathers offered him a job running the library, since he was spending so much time there, they said, “Would you like to just take over the library?” So he took over the library, and quickly began developing his own classification system.

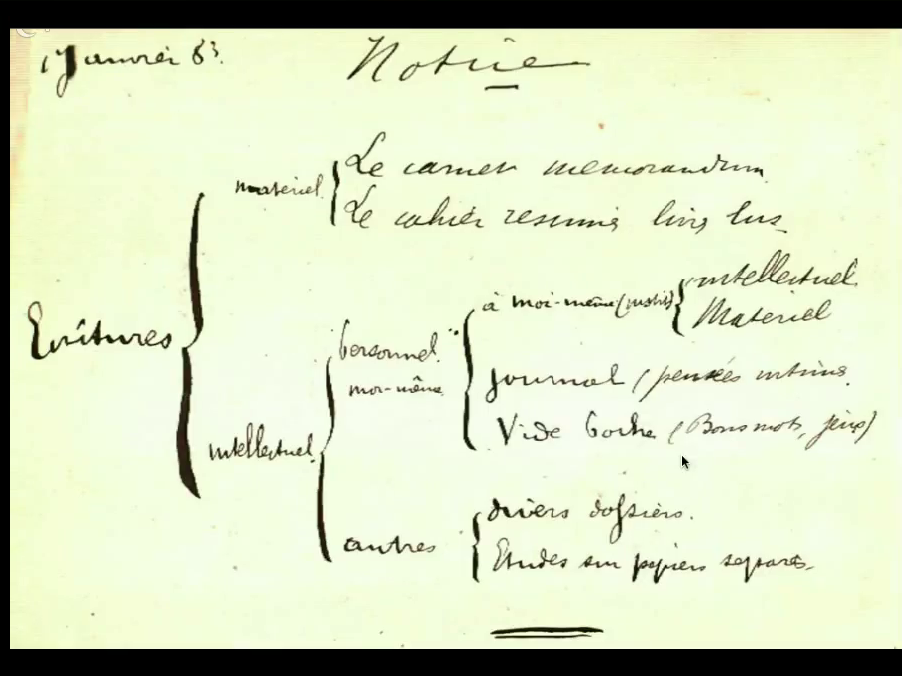

Otle’s personal classification system that he developed when he was about 15 for his own collection.

He began to organize the books in the library, and that was his great pleasure. He was also an obsessive diary-keeper. I’ve seen the diaries; every couple of months, he would fill up a book with these long, introspective diary entries where he would talk about his philosophy of information, how he was collecting information, and how it would all take his experiences and organize them and make sense of them, and he started to glimpse this idea that he had about what it might take to organize the world’s information. And he was doing that at a fairly young age.

But after school, his father was pressuring him to take over the family business, so he went off to law school to try to establish himself in the world. He got married, lasted about a year as a lawyer and and just hated it, decided it was just misery. He couldn’t do it. But during his brief period as a lawyer, he did meet another lawyer, a guy named Henri La Fontaine, who was a little bit older than him. They had some shared interests. They were actually assigned a project to catalog all of Belgian law at that time for a lawyer named Edmond Picard. They were trying to create a system to catalog the Belgian legal code.

After Otlet decided he was done with the law, he and La Fontaine continued their partnership and started to think about how they could approach other domains of knowledge in this way. They began working on a project to create a bibliography of everything that had ever been published in the field of sociology, which was an emerging field at the time. So they starting cataloging the sociological literature. They worked through that process, and then they began to think about other domains. As time went on they started to cultivate this idea of creating what they began to call a universal bibliography. And they decided that they would begin to sketch out a plan for creating a universal repository of all the published information in the world.

Otlet was like 23 years old at the time. It was a crazy ambitious scheme, but he did have some family, he was able to choose how he wanted to spend his time, and decided that this was going to be his life’s work. His partner La Fontaine at the same time had continued his legal career and was on his way to becoming a Belgian senator, and becoming quite an influential guy. So their partnership began to cement and take off. They actually formed a formal organizational body, and they began this project of creating this universal bibliography. They took the card catalog technique that had been developed. They had seen Melvil Dewey’s classification system and thought it had some interesting ideas. They took that and adapted it.

But this is where Otlet starts to develop some real original thinking. Otlet had spent enough time around libraries studying techniques for organizing information that he began to see the limitations of certain conventional approaches to library cataloging. He felt like librarians had been too fixated on the problem of books, and that essentially they had defined their role as organizing a book on a shelf and putting it into a categorical scheme. He felt like that wasn’t enough. He felt like, given the incredible explosion of information that he was already seeing in the 1890s, that that approach was just never going to scale and would eventually fail, and that humanity would need a much more robust system in order to make sense of this proliferation of published information.

So he wrote a little essay called “Something about Bibliography” and in it (again he was in his 20s) he really provided the intellectual blueprint for all of the work that would follow. He basically came up with this really insightful approach which was based on the premise that you have to go inside the covers of the books. The book itself is not enough; you have to go deeper than that. He felt like there was so much information locked inside of those books, and if you could develop a system that was able to penetrate the covers of a book and unlock the information inside and then recombine that, then you might have something really interesting. This was his core insight that really informed the rest of his work.

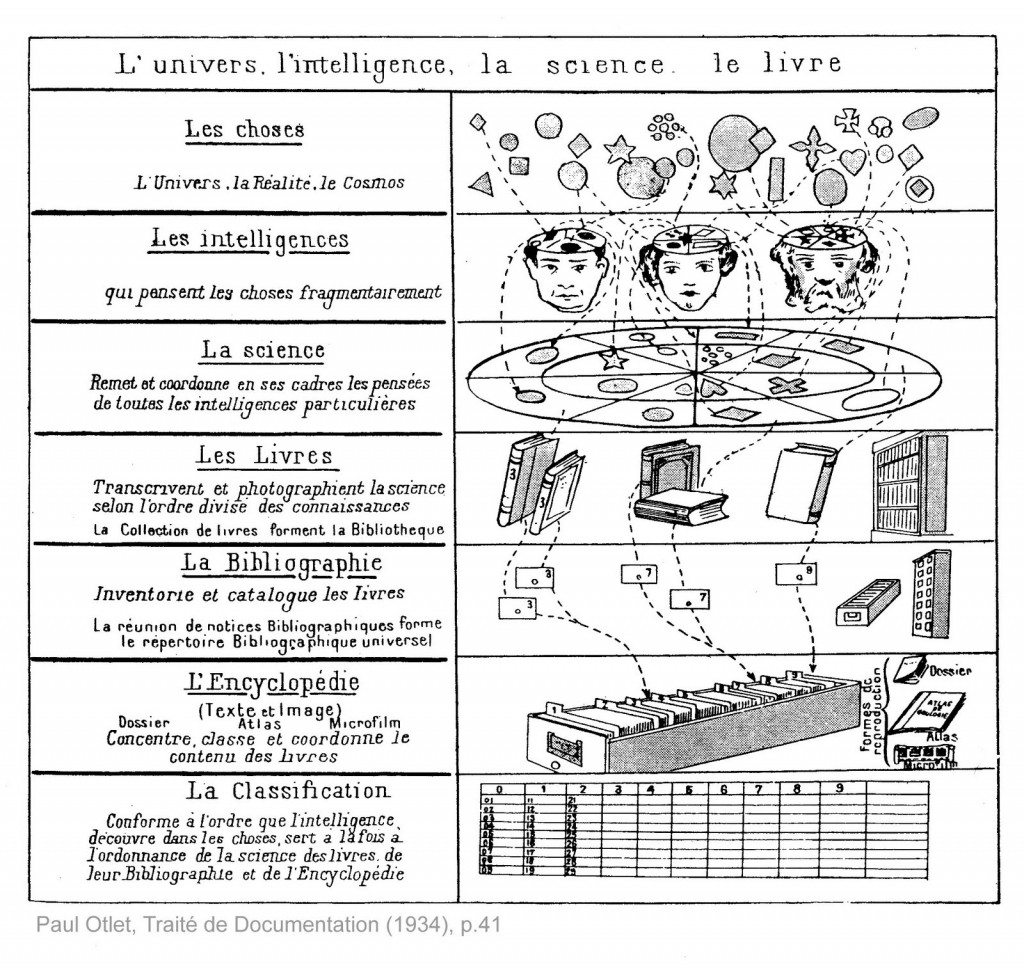

This is the diagram where he really kind of lays out the whole idea. The idea’s that you have this cataloging system that’s physically embodied in the card catalog, that has cards that pull information out of books. The books contain ideas, which come out of people’s heads, which have Lucky Charms coming out of their heads… But you get the idea.

This is another illustration of his that conveys the concept.

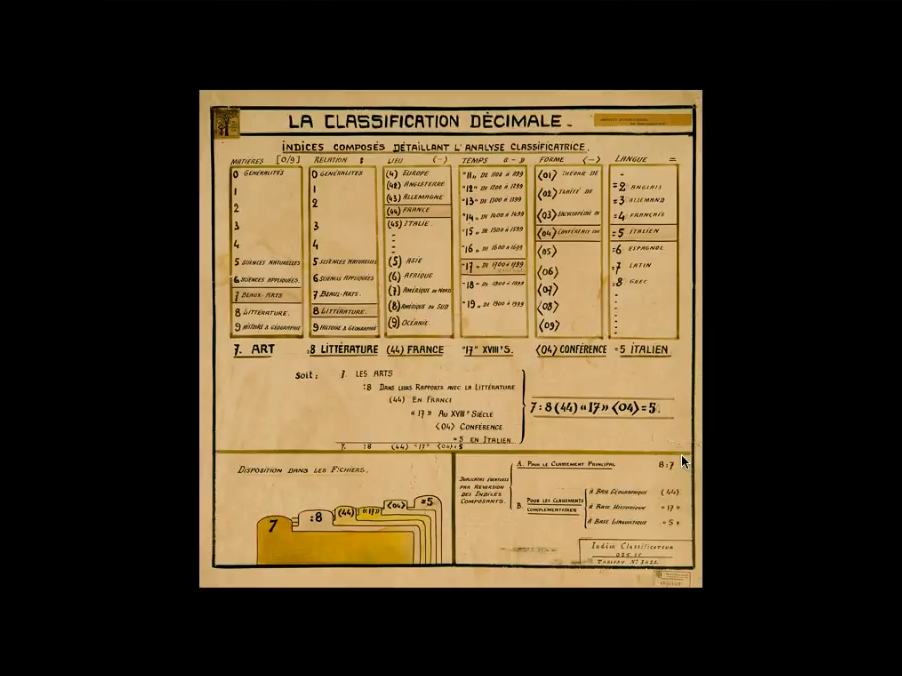

So that’s an interesting insight, but it’s not enough to just have that insight. What do you do with that? Over the years that followed, Otlet and La Fontaine began to develop what they called the Universal Decimal Classification. It’s an incredibly sophisticated, complicated, almost synthetic language that tries to describe the whole universe of ideas, and creates a set of tools for encoding the relationships between ideas. So the idea is everything is converted to a decimal classification scheme like Dewey’s system where everything is based on a numbered point system that’s related to context, but Otlet’s big contribution was to then say, given a particular topic that’s represented as a number, you could then relate that topic to another topic by means of symbolic language. So if look [in the preceding image], there’s different punctuation marks, colons and parentheses and quotation marks and equal signs and brackets, all of these mean things. They mean something about that relationship. It’s the history of this topic, in this country, written in this language, these sorts of things. You can create these semantic relationships between topics. He called them “links.”

So it’s very much like a hypertext kind of idea. You can have a whole universe of topics and you can map the relationships between those topics, and then map that back to a source in a book. And, importantly, map the relationships from an idea in one book to an idea in another book, or another document, and then you can create those pathways through the whole literature by using this system. So this was Otlet’s big idea.

In 1900, he and La Fontaine went to the Paris World’s Fair, the World Expo of 1900, which was this incredible spectacle. It must have been an amazing thing to see. They basically raised all of downtown Paris and put up these giant pavilions that were made of plaster of Paris that represented every country in the world and all these different exhibits on things like industry and electricity and you name it. The whole city of Paris was electrified. Most people were seeing electric lights for the first time. They saw moving pictures for the first time. Thomas Edison was there. They saw moving sidewalks and escalators. It must have just been mind-blowing for people. It was this incredible spectacle. It was all on display in these several square miles of downtown Paris. Something like fifty million people came from all over the world to visit this thing, and then they took it all down. It all just kind of disappeared. But it’s fascinating. There’s amazing pictures and representations. This whole giant Potemkin village kind of thing was constructed and then it was all taken down very quickly.

But Otlet and La Fontaine were there and they exhibited their prototype of the Universal Bibliography and got quite a bit of attention there and met some interesting people. When the World Expo closed, they actually walked away with one of the grand prizes for the whole thing. So they generated quite a bit of interest that they were then able to leverage to expand the project.

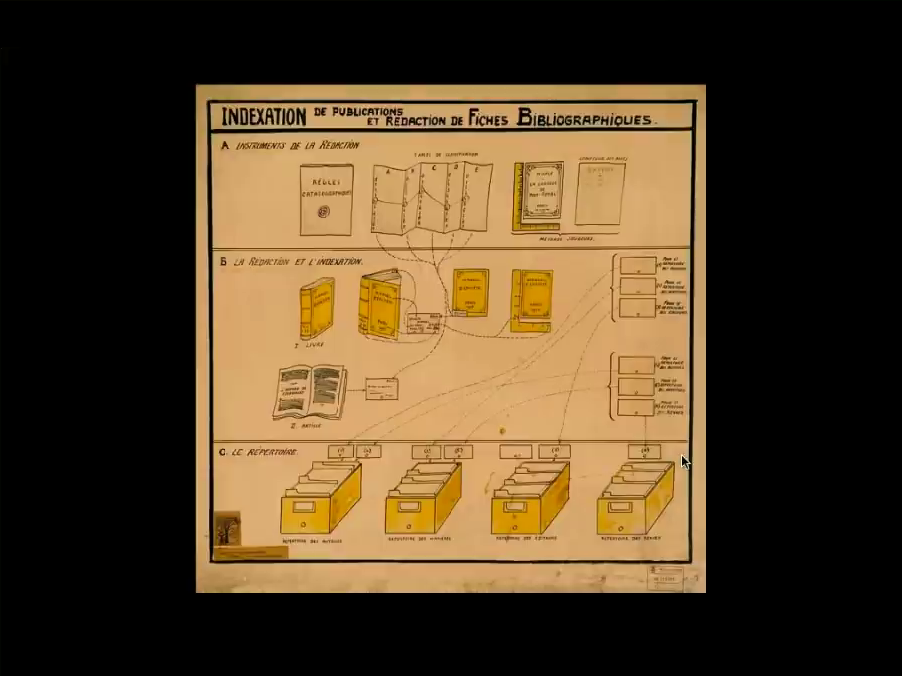

By this time, La Fontaine had taken a seat in the Belgian Senate and had some very strong government contacts. They’d gotten a lot of publicity, and they were able to convince the government to fund this project. So the project really started to take off. Within the next few years, they had managed to catalog 16 million individual entries on their cards, doing it by hand, basically. They hired a staff of people to work on it, and by the mid 1900s, you were able to send in a question by telegraph for a fee of four francs and the staff would then go answer your question and then they would telegraph it back to you. So it was basically a search engine, for a fee.

Things were taking off nicely. Otlet was starting to get very interested in a bunch of other things. As they were starting to create this catalog, they realized that they need to figure out how to govern it, what was going to be the entity that surrounded this thing? And he and La Fontaine got very interested in this whole topic of international associations. They were also seeing, as I mentioned, all these scholarly associations, these different international bodies starting to form. They thought this could all be of a piece. So they created what was called the Union of International Associations, which was meant to be an association of associations that was going to be the organizing body that would create standards and tools for all these international bodies to then publish their journals and archive all of the results in a single place.

Otlet also started an international newspaper association, with an eye to creating a universal archive of all the newspapers that were being published, and got quite a bit of support for that. As this all started happening, he started to see that there was an opportunity to expand the vision of this quite a bit. First beyond just the world of books, he stated to see that you could take these same principles and apply them to any kind of media, photographs, newspapers, audio recordings, movies (which were starting to happen). He was saw you could have one system that would encompass all of these things, and that perhaps there could even be more of a physical manifestation of this idea.

So Otlet started to make some interesting connections. There was a guy he met at the Paris World’s Fair named Patrick Geddes, who was a Scottish sociologist, more or less, who was very interested in the future of museums. He ran an attraction called Outlook Tower. It’s a camera obscura; if anyone’s ever been to Edinburgh it’s still there, actually. He had this interesting idea that museums could play more of a role in educating the populace about the world around them, not just being places where you went to see historical artifacts, but they could have more of a teaching mission. So he created these prototype museums called Outlook Tower that would let you learn about all of these different topics and how they related to each other.

Geddes also created these really interesting information visualizations he called “thinking machines.” The idea was to create these kind of topic maps between concepts using visual annotation, and he was very interested in using spatial techniques for organizing large bodies of information. He an Otlet had a pretty lively correspondence for a while, and Otlet began to really build on some of these ideas to think about how he could take this universal collection he developed and actually turn it into a museum.

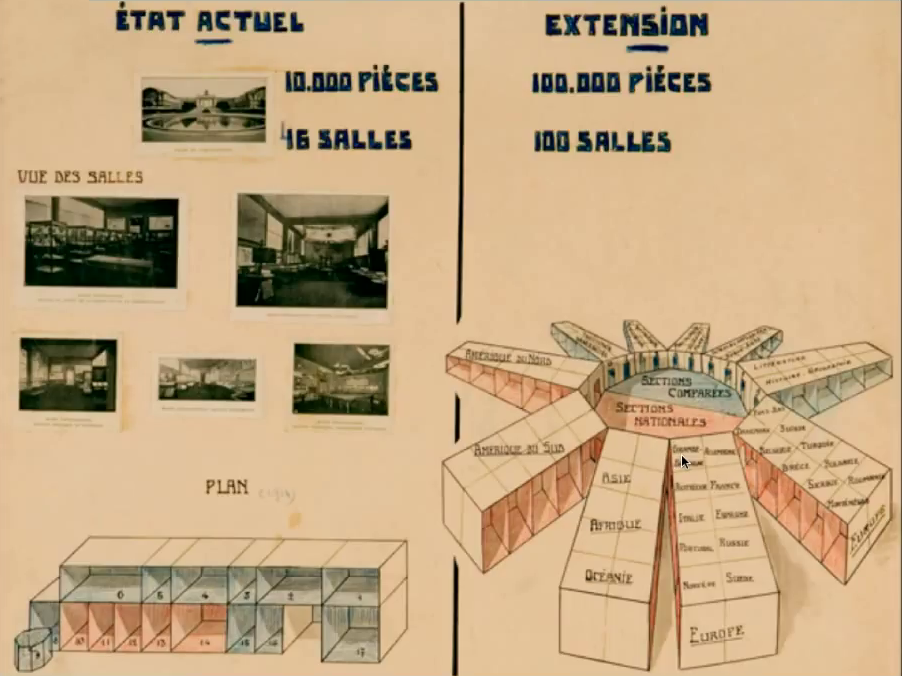

The idea would be to go beyond just cataloging books, to actually create a physical space you could walk through, where you could get exposed to all these different topics. Eventually he and La Fontaine were able to sell this idea to the Belgian government, who gave them space in this giant government building where they eventually created I think it was ultimately 160 rooms where they had exhibits on every topic you could think of. The history of every country in the world and zoology and astronomy and telegraphs, it was just this crazy ambitious scheme to create a kind of physical embodiment— The idea was that you could walk into these spaces and get exposed to a topic and learn about it, and if you were interested in going deeper you could then transition seamlessly into the catalog, where you could do deeper research into whatever that topic might be.

He was also influenced by a guy named Otto Neurath, who was a Viennese philosopher and sociologist who was also very interested in museum work. One of Neurath’s contributions was this visual pictographic language, which he called ISOTYPEs. The idea was to create an icon language that was independent of any particular written language. So think of the sign on men’s or women’s room doors; that’s an example of an Isotype. He also had a lot of interesting back and forth with Otlet about some of these ideas of how do you make something really internationalized and universally accessible.

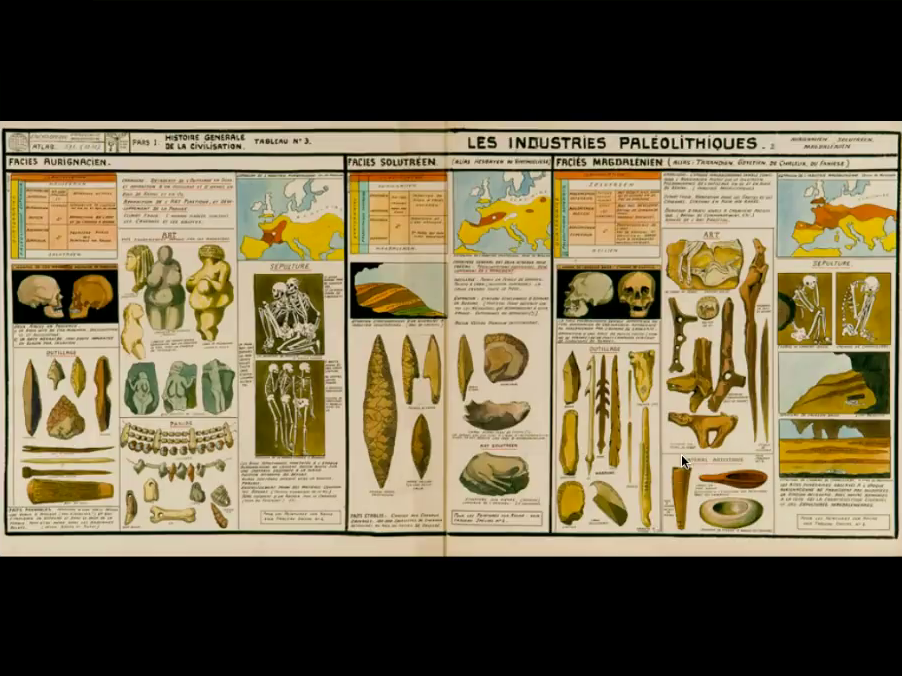

This is an example of one of the exhibits in the museum. You can see it’s not your typical kind of museum display. There’s not a lot of stuff behind glass cabinets. These are infographics, kind of. Take a topic like mathematics or electricity, and sort of lay it out with a combination of words and images and give people an overview of that topic.

This was the telegraph room where they had a lot of interesting devices that they were presenting.

Then these strange contraptions. I don’t even understand what this thing does, but it looks cool.

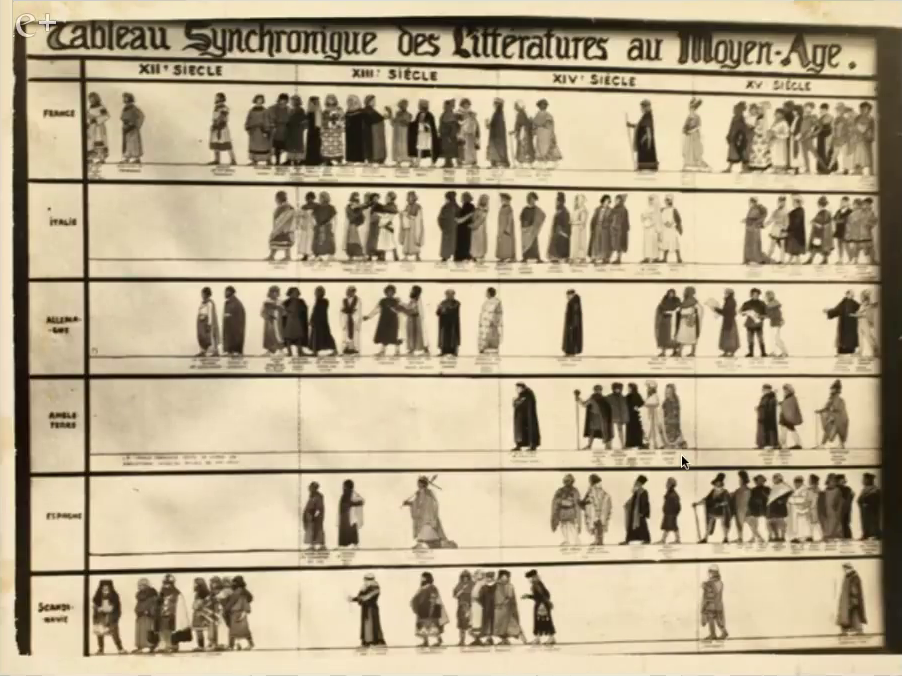

This is an example of some of these information diagrams. They started to work with some graphic designers on the form of these things, and this was a time table of the history of the Middle Ages where you can see it’s laid out in a timeline and then they would use this as a launching point to go deeper into the catalog.

Here’s another piece that’s an overview of prehistoric tools. You can see there’s almost a very hypertext-like feeling emerging here. It’s words in little chunks, blocks of text. There weren’t a lot of things out there at the time. Most books were written in long narrative, but these are kind of like proto information graphics. There’s not a lot of precedent for this kind of thing at this time, and I think it really starts to anticipate the idea of stacked collections of information that are links to other pieces of information in an accessible way.

So all of this was taking shape, and Otlet continued to broaden his circle of contacts. Eventually he made contact with a guy named Hendrik Andersen, who was a very interesting guy, a very sort of eccentric Norwegian-American sculptor who was best-known for having this very intense letter-writing affair with Henry James. A very odd duck, but he had some interesting ideas of his own. He was very interested in this idea of creating what he called a World City. It was a very utopian idea of creating a new city that would serve as the headquarters of a kind of utopian world government. Andersen was living in Rome and he was very inspired by the classical idea of Rome. This was all in the run-up to the formation of the League of Nations, this idea that there could be a universal governing body for the world that would prevent future conflict and warfare.

So Andersen commissioned an architect who sketched out this grand scheme and he and Otlet discovered each other and found that they had a lot of complimentary ideas, and eventually they decided to join forces so that the plan for the World City eventually included Otlet’s universal library, which by this time he had started to call the Palais Mondial, the World Palace. The idea was that as the World City was the physical representation of this idea, the World Palace would be the intellectual heart of it where all of the world’s information would flow, and be distributed and organized.

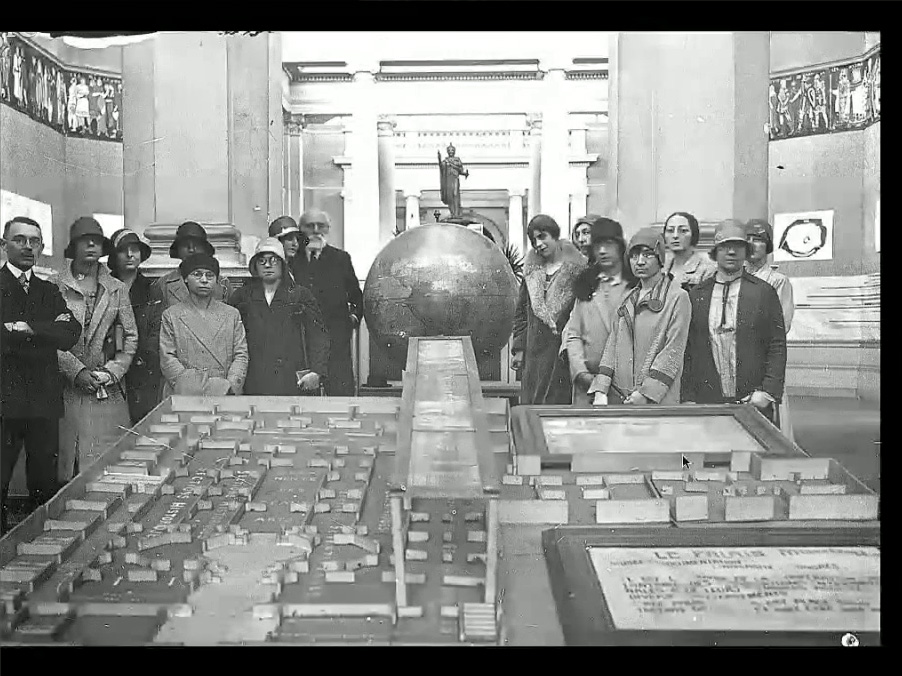

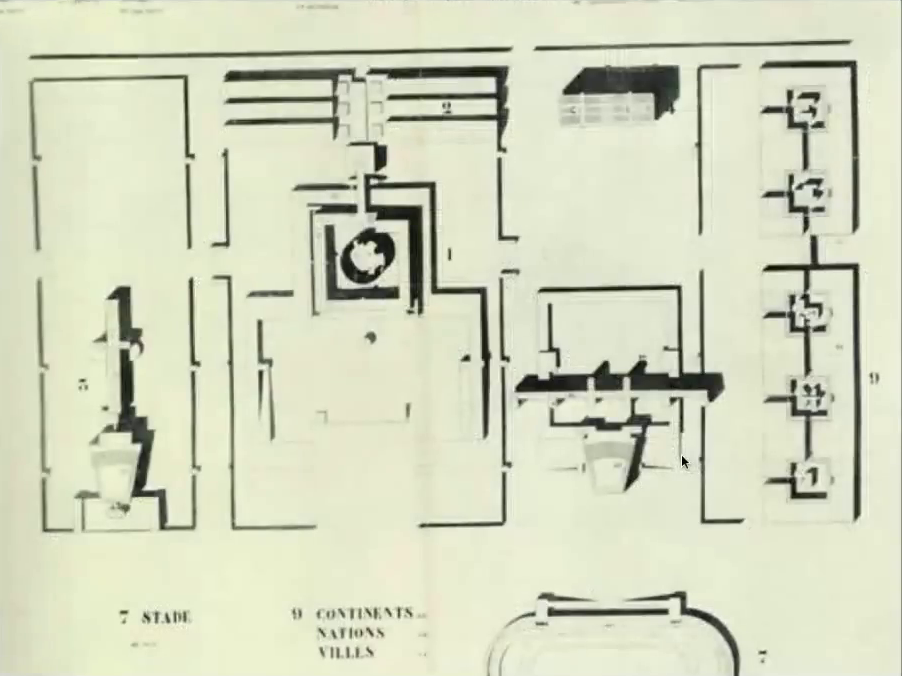

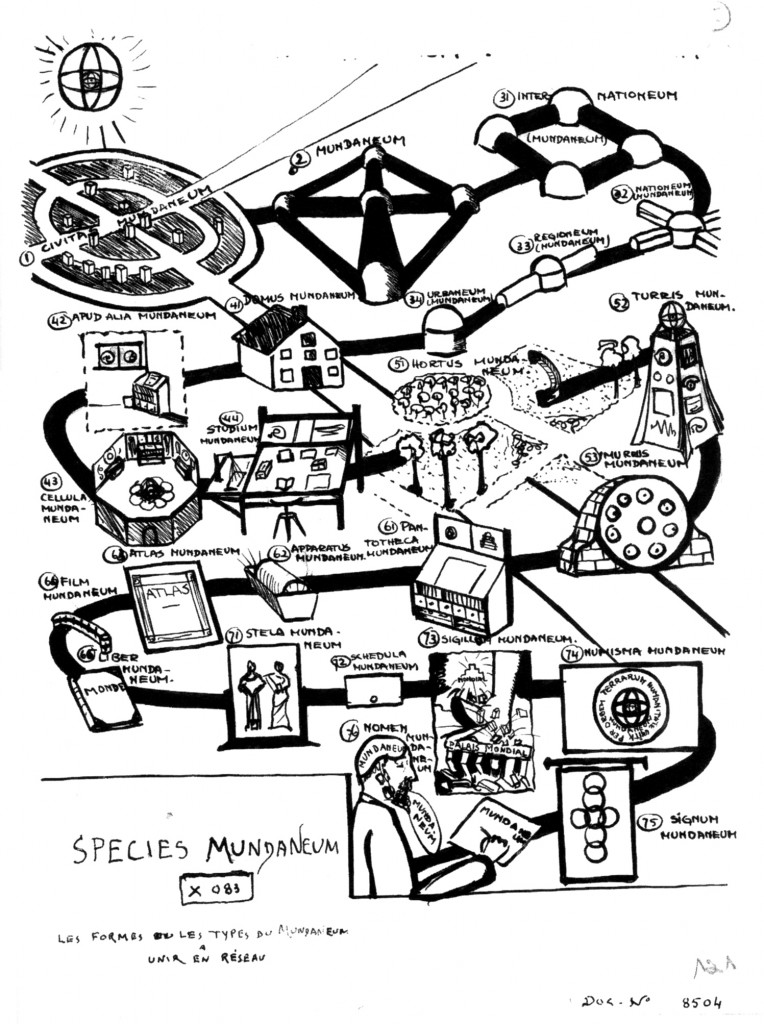

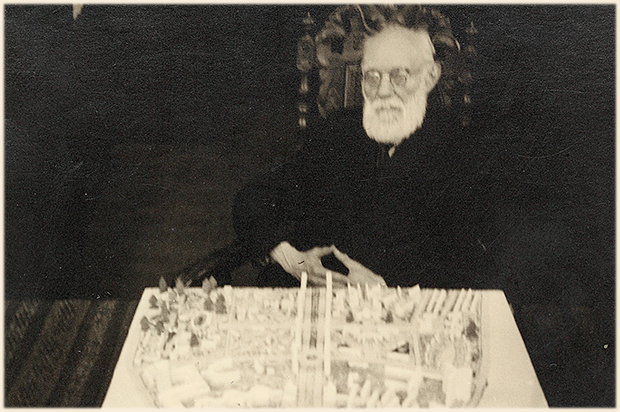

They started developing some fairly elaborate plans for what this would all look like. Here’s a picture of Otlet with a diorama of the the World City, which included a place for his collection. And these are some additional plans.

Again, the idea is this is all part of a much large organizational scheme in which all of the world’s governments and international bodies would all agree to collaborate and participate in this universal network of associations. A very ambitious idea.

As time went on, they continued to evolve the thinking about this, but by the end of World War I… Otlet was actually very active in the eventual formation of the League of Nations. he was a real prolific writer, he penned a lot of editorials and articles during the war. He was actually recognized when the League of Nations was formed as one of the early forebears of it. […] And at one point it looked like right after the War, they were hoping that Belgium would be selected as the headquarters of the League of Nations. Belgium had been a neutral country which was overrun and the Belgian government made a big push. Otlet and La Fontaine were very involved, and unfortunately they were not successful. The headquarters of the League of Nations went to Switzerland instead, and Otlet began to become more and more disillusioned with the process. He felt like the League had been taken over by bureaucrats and that they weren’t really fulfilling their vision and became much more conciliatory and much more about how governments are protecting their own interests, and the sort of idealism that he and Andersen hoped for…it seemed really disillusioning.

By the 1920s, political influence had shifted in Brussels as well and a more right-leaning government had come into power and Otlet started to lose some of his support, gradually a lot of the early progress he had made towards realizing this vision started to slow down. He began to lose support, his own resources became strained, and he eventually began to retreat into himself a little bit, and to spend less effort on trying to build this thing. He spent more time writing and thinking about trying to further refine his ideas, and became much more inwardly focused.

But it was during this period that he really produced his most important work and began to really think in a much more forward-looking way about the possibilities of this networked world that he had started to imagine.

I’m going to share a quick film clip from a documentary that was made about Otlet a few years ago in Belgium by a woman named Francoise Levie. It’s an excellent documentary called The Man Who Wanted to Classify the World. This is just a short clip that gives you an idea of some of what he was starting to think.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qwRN5m64I7Y

That was 1934, so…pretty good.

So what happened? Why has nobody heard of Paul Otlet? Well, as we know, a few years later things happened in Belgium. The Nazis marched in 1940 and promptly destroyed much of his work. Otlet had already begun to retreat from public view a bit, but a lot of his collection and archive were still there. The Nazis came in and they were quite interested in Otlet. They read about him, they knew that he had a lot of foreign contacts which they were very interested in. They were also in the process of building their own sort of Nazi library that was going to serve this big university they were building. They were attempting to collect everything that had been published about subversive doctrines like Freemasonry and Catholicism and Judaism, and they were very interested in seeing what Otlet had that they could pilfer. And they were sort of interested in his catalog, too.

But they couldn’t really make sense of what he had done. It looked very chaotic to them. They didn’t really understand what they were looking at, and they ended up destroying most of it. They actually destroyed something like 70 tons worth of material and just threw it out to make room for an exhibit of Third Reich art.

Otlet died several years later in 1944 just at the tail end of the War and was promptly essentially forgotten. Although he continued to refine his thoughts a little bit during the War. He had some ideas about televised classrooms. This would be called distance learning today. The ability to project books on screens, he eventually had this idea that you could sit in your armchair with a screen and pull up a book that was stored at a great distance and you could browse it.

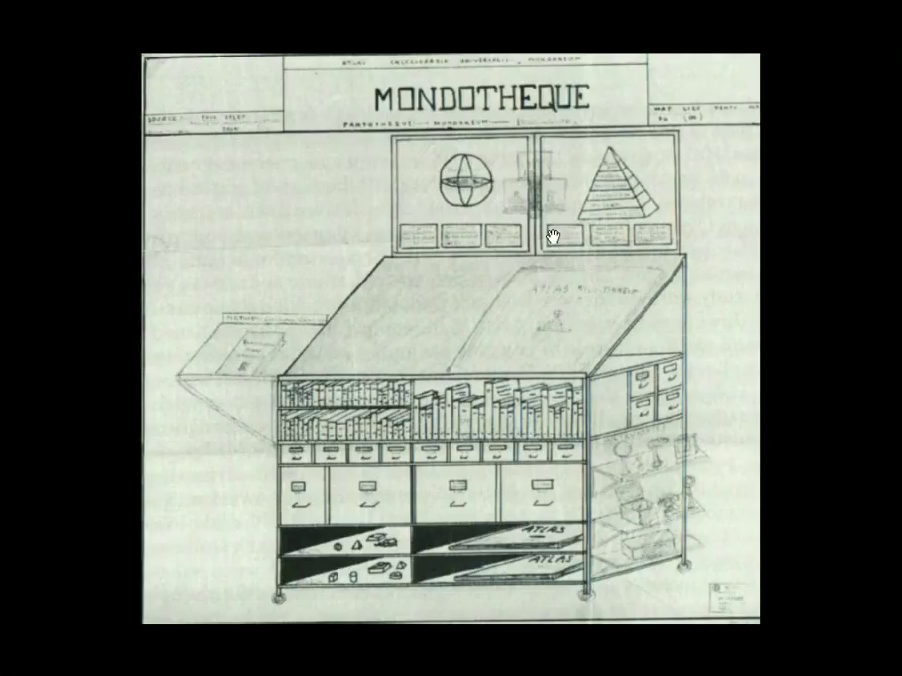

He even had this idea for a sort of prototype workstation that was called a Mondotheque. The idea would be that you could have a personalized collection books that you could then…

This was somebody [trying] to recreate what he had in mind. It’s connected to a radio transceiver, and you could pull up information and have it syndicated back to you if you wanted to create your own custom portal on a particular topic.

So that’s really where Otlet’s story kind of ends, in 1944. This was one of his last ideas and really his legacy was largely forgotten. Not everything was destroyed. Some of his card catalog did survive and a lot of his papers were stored in a warehouse in Brussels and some of them were actually scattered around the subway system for a while. There’s now a museum dedicated to him, and people still show up with reams of paper they discovered in the Brussels subway twenty years ago and they drop it off.

But he was really pretty much forgotten for about twenty years, until a guy named Boyd Rayward, who was a graduate student in library sciences at the University of Chicago sort of stumbled on this paper trail and started writing a dissertation about him and went to Brussels and found his office had basically been left untouched for 25 years. There was rainwater dripping from the ceiling and mold everywhere and he went in and started to excavate his stuff for his dissertation.

At the time, Otlet was just kind of an interesting, curious historical figure who had some interesting ideas about library cataloging. It really wasn’t until the 1990s that people started to understand that what he was talking about was really something like hypertext. People didn’t quite know what to make of his ideas, and the passages that are now so visionary now are overlooked until there was historical context for understanding what he was talking about. So I think he’s taken on a new relevancy in the last few years, and I think he’s finally starting to get his due as one of the real forerunners of the hypertext age.

There’s now this museum in Mons called the Mundaneum. Mons is a town about an hour outside of Brussels where they had tried to resurrect his legacy. Interestingly, Google has a big data center in Mons, and they discovered the Mundaneum and are now sponsoring some events there and helping to support them, which is kind of ironic. And they’re now trying to digitize his collection and make it searchable, so you’ll actually be able to find his stuff on Google; a lot of his archive material is still locked in archival boxes over there.

So what can Otlet tell us about the Internet today? Well, a couple of things. If you look at the Internet today… The Internet famously has no top, has no organizing principle, it’s very bottom-up, it’s very self-organized and that’s one of its great strengths. But what Otlet imagined is something much more organized, and I think one of the important contrasts [is] as much as he really anticipated something like this networked world, it’s important to note a couple of key differences.

Image via multimedialab.be

First, he didn’t really envision any commercial activity happening on it. He thought maybe there would be some bookstores, but that was about it. He did not see this as a place to buy and sell stuff, he saw it as a place for scholarly inquiry and for fostering collaboration and cooperation among the world’s governments and non-profit associations primarily, and as a place for pursuing intellectual inquiry first and foremost.

He also saw it as a very managed environment. He did not envision the kind of anything goes, bottom-up nature of the web as it is today. He envision it as something that would be much more managed by a network of associations with a central coordinating point. And that whole idea is really completely counter to what the Internet has become or how it was really designed. It was designed specifically to be a flat, distributed network. I’m not saying Otlet’s idea was better, but it is an important difference that he envisioned that we would have a lot more control in place and a lot more of a curated aspect where you would have networks of catalogers or experts in particular topic areas who would decide what was to be considered for inclusion in the collection.

But that said, I think I think the mechanics of how he imagined the network working are less interesting than the spirit behind it. From my point of view what he really offers is a much more altruistic, purposeful idea of what the network could be. It’s one that’s driven much more by a higher ideal of helping humanity progress towards a more peaceful, intellectually fulfilling world, and one less driven by commercial considerations and self-gratification that was see driving so much of the activity on the Internet.

So I think it’s less about the particulars of like, would this be a plausible environment. It’s hard to imagine anything being built like this today, but I think the spirit behind it is interesting and I hope maybe a useful reference point for thinking about what the network might become.

That’s Otlet at the very end of his life, and this is the book I wrote about him.

Thank you.

Audience 1: I’m wondering about the value of knowing about this to [inaudible] and also in sort of a general education sense. What would you say the value is to undergraduates from any discipline of knowing about Paul Otlet and what he had envisioned. Is this dreaming of what the Internet [could be?]?

Alex: I think at a practical level, there are some interesting specific ideas he had that are provocative, around for example the idea of different kinds of link relationships. If you think about the Internet today a hyperlink is a very sort of dumb proposition, it’s just saying “this links to this.” It doesn’t tell you why or what the nature of that relation is. So I think there are some interesting ideas about more nuanced kinds of link relationships that I think could be interesting things to explore.

I also think a lot of his ideas about this top-down organization of information, I think there’s a lot of applicability to some of the work going on in the Semantic Web space, and there are some echoes of that idea in there. But beyond that kind of stuff, I think that stuff might be interesting and useful to ponder a little bit.

But beyond the story itself just being interesting, to me anyway, I think there’s a lack of historical awareness in terms of understanding how we relate to technology and I think that’s partly a function of the high-tech industry [being] so forward-looking and predicated on this whole idea that you always have to be looking ahead because that’s how demand gets generated for the next cool gizmo. And I think there’s almost a subtle pressure that works against [] that’s almost encouraging this kind of state of amnesia where we either forget about the past or kind of deprecate it in some way. And I think stories like Otlet’s I hope are an invitation for people to ground themselves a little more in the heritage of where we all came from. That’s just an inherently good thing; it gives you a little bit of perspective that the world didn’t just change instantly in the last twenty years. There are some longer-term dynamics at work that led to the world we’re in today. I think it’s good to encourage people to have a little bit of a longer view of things.

Audience 2: I was wondering, when you put up the image of the folks who actually do the cards, it looked like it was a largely female, if not all-female, workforce. Is there any documentation or histories or other record of those women and the work that they did, and who they were?

Alex: It’s a good question. After the book came out, a woman wrote to me whose parents had both worked on the Mundaneum project, so it was a man and a woman, and she said he had heard stories about Paul Otlet growing up. But I think you’re right. I think a lot of the staff at the Mundaneum were largely women. I do not know of a lot of archival sources… I know one of them was La Fontaine’s sister, but I don’t know that there’s a big paper trail. I’m sure there are records of their names and things, but certainly it’s noticeable that they seem to be largely women doing a lot of the work there.

Audience 3: Just to follow on that. The history of early computing, of course, the first computers were women who sat in rooms and did computations, and the ENIAC programmers were all women. So I think there a really interesting connection there when looking at these alternative histories, upending out perceived notion of the history of computing. A very excellent parallel.

Alex: Yeah, obviously those people were playing a critical role [inaudible] the 16 million card catalog entries.

Audience 4: I couldn’t help but think that the Internet (if you want to call it) that Otlet envisioned was one that librarians would have built. It’s the kind or orderly, everything’s organized, everything’s classified sort of control. But my question is, you describe him as sort of having been forgotten. I think it’s definitely true that he’s forgotten within the sort of popular—

Alex: I would say outside of library sciences circles.

Audience 4: But, did people like Vannevar Bush or Tim Berners-Lee, were they aware of this vision?

Alex: That’s the $64,000 question. I looked really hard for that paper trail. I think the best you can say is there’s some circumstantial evidence that Otlet’s ideas were in the air during the period when Bush was working on his essay “As We May Think.” Bush was notoriously bad at giving credit to anybody else. If you read that whole essay, I think there’s not a single footnote in it. It’s like it all just sprang out of his head which, maybe. But there was a conference in Paris in 1937 where Otlet and H.G. Wells, who was also the famous British science fiction novelist who was very interested in this topic. Wells and Otlet knew each other and influenced each other.

Wells also had this idea of what he called the World Brain. He wrote these essay about this networked world where information would be freely available. Around this time, both became very interested in microfilm, which is what Bush was working with. A guy named Watson Davis, who was eventually the founder of ASIS, was at that conference, and he knew Bush. So there’s like two degrees of separation from Bush to Otlet, but there’s no footnote you can point to and say “Aha!” There’s no smoking gun, but it seems like the ideas were out there, and that’s as far as you can take it.

Further Reference

Original event listing at the MITH web site.

Boyd Raywards’s Otlet page, with various articles and papers he’s written about him.