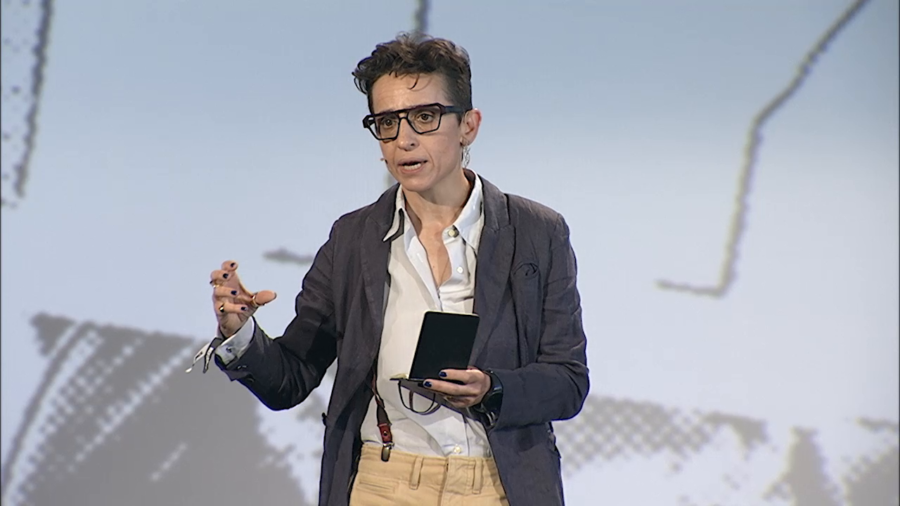

Farai Chideya: We have already heard some amazing speakers, and right now we’re going to continue by talking about the conspiracy trap, with Masha Gessen. She’s a Russian and American professor and author. She’s a professor at Amherst and she is the author of The Man Without a Face: The Unlikely Rise of Vladimir Putin, and in October her new book is coming out which is called The Future is History: How Totalitarianism Reclaimed Russia. So please welcome Masha Gessen.

Masha Gessen: So I’m going to start with an unfunny joke. You’re supposed to start with a joke, right? And the joke actually comes from a 1940 entry in the diary of Victor Klemperer. Victor Klemperer was a linguist who kept a journal of the Hitler years. A very detailed, very brilliant journal. And he quotes this joke that Hitler has run into Moses. And Hitler says to Moses, “Tell me the truth. You set that bush on fire yourself, didn’t you?” [scattered laughter] Some people think it’s funny.

I think that it’s hilarious. But I also think it’s illuminating, in the sense that the reference in that joke is to the Reichstag fire, right, which a lot of people in Germany believed that the Nazi party had set itself in order to justify the political crackdown that followed.

But also to me it’s important because it’s illustrative of something else. It’s illustrative of the way that conspiracy thinking contaminates life under a particular kind of regime. Basically in the joke, Hitler is also contaminated by conspiracy thinking, right. So people believe that he’s a conspiracist, people believe he set fire to the Reichstag, and they also think that he is a conspiracymonger and he thinks that Moses is a conspiracist, right.

And that’s something that I think is diagnostic. Under a particular kind of regime that kind of conspiracy thinking becomes endemic. And I would argue it’s very very dangerous. Now, when I talk about a particular kind of regime what I’m talking about is the kind of regime that forms on the promise of simplicity. And when we talk about a global epidemic of something political, it’s actually very difficult to put a term on it because it’s not always authoritarianism that we’re looking at around the world right now when we talk about a crisis of democracy. It’s not always the rise of the far right, sometimes it’s the far left. Sometimes it’s a kind of populism that’s difficult to sort of place right or left.

But what they definitely have in common, these people who are rising all over the world, these kind of anti-political politicians, is that they speak to a fear of complexity. They speak to the way that people feel homeless, at a loss in a very very complicated world. And they promise simplicity. They usually couch that promise in a sort of imaginary past. They talk about traditions and traditional values or making America great again. But really what they’re talking about is that things can be really simple. And that’s what gets them elected.

Now, conspiracies are perfect for simple thinking. Because conspiracy is by definition something that explains everything. A really great conspiracy explains something that has already happened and something that’s going to happen.

Truthers are conspiracists, right, people who believe that 9/11 was organized by the US government. Birthers are conspiracists. Pizzagate is a conspiracy. I mean, it’s a perfect conspiracy, because it explains sort of why people go to this restaurant and why it’s owned by the former partner of a Democratic Party operative, and it ties everything together and the world suddenly stops being complicated and looks simple. And Russiagate is a conspiracy. Russiagate is perfect. Because Russiagate explains how we got Trump and how we’re going to get rid of Trump. Russia elected him, and once it all comes to light, he’s magically going to disappear.

Now, here’s where it gets complicated because wait a second, didn’t Russians actually interfere in the election? Didn’t they hack the DNC? Didn’t they try to infiltrate the campaign? Didn’t they have a meeting with with Don Jr. and dangle the promise of some sort of compromising information on Hillary? Yes, they did.

Here’s where it gets really complicated. The possible existence of a conspiracy is not an excuse for conspiracy thinking. Even while we wait for this investigation to unfold and maybe hope that something comes of it, when we engage in conspiracy thinking, when we cling to this idea that we know how we got Trump and and we know how we’re going to get rid of Trump, and there’s this one thing that explains everything, we’re doing grave damage to our own ability to think and to our own politics. And to our own ability to act.

Now, how does that work? Why is conspiracy thinking so terrible? Well because, again, it’s simple. It prevents us from looking at the complexity of the world. It prevents us from looking actually at the complexity of that whole Russia intervening in the election situation. Or maybe complexity is not the the exact word for this thing. It’s a mess, right.

And I’ll explain what I mean. If you read The New York Times interview with the president yesterday, I mean here’s a man who can’t grasp the meaning of health insurance. Or federal employment or political institutions. Or parades. Or dinner. Or a handshake. But somehow we still believe that he can grasp the meaning and the import of a conspiracy. That he can keep a secret for many months. That he can actually hold onto a thought for many months. This is funny but you know, this is a kind of giddy, hysterical laughter, isn’t it?

What’s wrong with thinking that this president can hold onto a thought? What’s wrong with thinking that he can engage in a conspiracy? Well, it’s not reality. And getting divorced from reality is a very very dangerous thing in life, in politics, in action, in everything. We have to stare at the fact that this is a man who doesn’t have a grasp on reality that is our reality. Focusing on the Russian conspiracy interferes with our ability to see that. Because it’s in this one particular area sort of imbues him with abilities—mental abilities—that he clearly doesn’t seem to possess.

The other thing is that the Russia part of the story is a different kind of myth but very much a myth. In our imagination, Russia is a country that is run by an iron fist, by one man who gives orders. Or maybe doesn’t even have to give orders; he has thoughts that’re immediately carried out by a well-organized army of perhaps trolls or perhaps or soldiers, spies, whatever.

In fact— And we know this, right. This is reality that’s been established. The Democratic National Committee was hacked by two independent groups of apparently Russia-affiliated hackers who weren’t aware of each other. That’s not an accident, that’s the kind of mess that that state is.

The inroad that we’re definitely aware of that was made to the Trump campaign was made by a low-level lawyer who was really trying to advance the interests of her extremely corrupt clients, and dangled the promise of Russian government participation in the campaign that she was probably in no position to dangle.

Why was she doing this? Well, partly because she was probably lying. Partly because she was a con artist who was trying to con Don Jr. into taking that meeting and was successful in doing that. Partly also because whoever manages to make a dent in Russia sanctions imposed by the US government is going to profit greatly in terms of privilege and money in Russia, and so there’s a race on for that.

So as you see, it’s a complicated picture—it’s a very messy picture. This idea that Putin could give an order, could see his way clear to electing Trump through cunning interference in the American election and the American public space, gets us out of thinking about how messy it is.

Of course it also gets us out of thinking about who actually elected Trump. It wasn’t the Russians. I mean, even if we accept the theory that Russian interference played a decisive role in the election, the way that hypothesis works as it’s put forward by US intelligence agencies, is that Russians used information that they obtained in part by hacking the DNC to influence American public opinion. So that what would happen? So that Americans would vote for Trump. Because they’re the ones who elected Trump.

Now, there was a lot of chest-beating after the election about how journalists didn’t cover the white working-class enough, and didn’t have enough empathy—and some of that I think is very well-founded. But it hasn’t gone much beyond that, because we’re so focused on the Russia conspiracy, which gets us out of the predicament of needing to look at actual Trump voters. At needing to look at the fabric of American society. And gets us looking at Russia instead, which is so much simpler.

Three, what’s wrong with Russiagate and focusing on Russiagate? When we focus on it, we don’t focus on other things. And actually I’m a great believer in covering everything and writing about everything and talking about everything. But unfortunately human beings don’t actually have endless bandwidth. And no matter how large an army of journalists we have, we don’t quite have enough journalists to focus equally well on deregulation, on the destruction of the State Department—which has been absolutely decimated, on the destruction of other American institutions, and on Russiagate at the same time.

If you think I’m exaggerating I’ll give you an example. Trump met with Putin. This is the official meeting. The one that went on for two hours and fifteen minutes. Afterwards, Secretary of State Tillerson meets with reporters. Reporters asked him about what? Mostly about Russiagate. Even though his answers are going to be predictable. What they don’t ask him about it is what’s happened to US foreign policy in regards to Russia. There’s one question that’s folded into four other questions about sanctions imposed in response to Ukraine, and Tillerson, easily because it’s folded into four questions, just avoids answering that question altogether.

No questions about human rights in Russia. No questions about the ongoing political crackdown in Russia. No questions about the fact that just two weeks before that meeting, 1,720 people were arrested in a single day in Russia. The largest wave of arrests in a single day in decades. No question about that.

Six months ago that would have been automatic. The political crackdown and human rights in Russia were a cornerstone of US foreign policy. It would have been a no-brainer. No one would have even had to put it in their notes to be able to ask that question because that would have been the first question.

And that’s not just talking about Russia, although that’s obviously hugely important and hugely important to me, but it’s talking about what’s happened to the institutions of the American state. What’s happened to the State Department, which no longer focuses on human rights. Which no longer looks at political rights in other countries. Which has actually lost its entire upper management level. Which is not functioning. No questions about that because we’re focused on Russiagate. And that one example of that particular press conference is very very clear.

And number five, and this I think is the most important thing. When we talk about the conspiracy, what it obscures is the future. We talk about what happened. We have hopes of how magically it’s going to get rid of Trump. And you know, I keep using the word “magically.” Why do I use the word “magically?” Doesn’t impeachment happen automatically? Well, it doesn’t. Impeachment has to be initiated in the House and then put through by the Senate, and both of the houses of Congress are dominated by Republicans who don’t seem to be on track to initiate impeachment no matter what kind of malfeasance is demonstrated. Is the House going to be flipped during the midterm elections? Well, not as long as the Democrats are focused on Russiagate instead of focused on flipping the House.

But that’s just the immediate future. That’s the next six, eighteen months. I’m talking about the other future, the long-term future. The future after Trump, which is going to happen. Even if he stays on for two terms. Eventually, because nothing lasts forever, Trump is going to end. And where are we going to be when that happens?

Remember, he got elected on the promise of simplicity. He got elected on the promise of a return to the imaginary past. The way to address that is not to just to rebuild the Democratic Party. It’s not to address the fact that the Democratic Party lies in ruins and the Republican Party lies prostrate in front of Trump. But it’s to actually think about a different message. The only way to counter a message of the imaginary past is to talk about the glorious future.

But we don’t have a vision of the future that’s put forward by the Democratic Party—or anybody else. The resistance is resisting what Trump is doing right now. The resistance largely is based on the premise, which is very much the premise that was advanced during the Democratic campaign, that things are good or were good before Trump came to power and need to be preserved as they were. That changes to those— Remember Hillary’s message, “We’re great because we’re good?” That’s “we’re good in the present,” right. There’s no promise of the future there.

And of course the resistance, as in any situation of political crisis, has to focus on things that need to be salvaged. But someone needs to be thinking about the future. Because the whole reason that living in a complex world is so frightening is because people can no longer imagine their future. This is what the great psychoanalyst and social psychologist Erich Fromm wrote about in 1940 in his book Escape from Freedom when he talked about how ruthless people feel when they lose their ability to predict what’s going to happen to them in the future. That is very much the predicament of Americans who voted for Trump.

And there is no vision that anybody is offering to them. Or even to those Americans who didn’t vote for Trump. We need people thinking about what a different world is going to look like. Because we’re entering a different world whether we like it or not. But we have very little idea of what it looks like. And as long as we focus on conspiracies, as long as we focus on something that promises to make the world simple, we’re not talking about the future. In fact, we’re obscuring the future.

So how do you practice defiance against that? Defiance against that is actually—it sounds pretty simple. You engage with reality. You take every piece of news critically. Not as confirmation of your idea that there was a conspiracy. Not as confirmation of your already-existing idea of what happened and what’s going to happen. But as something that yes, exists in context, but is also just what it is. Just what you’re learning today.

But more important that, you engage with other people. You act with other people. You engage with them offline. Conspiracies are also terrible because they pull you more and more, further and further into the online universe of ever-spiraling conspiracy theorizing. You engage with people whose ideas don’t coincide with your own in every way. And you engage with people around things that aren’t the conspiracy. That are reality and that are the future. And that’s how you get out of the conspiracy trap. That’s also how you get to be defiant.

And we have ten minutes for questions.

Ethan Zuckerman: So, thank you so much. That’s some of the most clear and provocative thinking I’ve heard about this particular moment that we’re facing in time. But it’s also debilitating in how depressing it is in some ways. Because it’s not only that we’re having trouble looking back, but looking forward. I’m curious if and where you find hope for this future-positive vision that counters of this very scary narrative that we have to return to some sort of imagined past. Where do you find hope within the current political space here and elsewhere?

Masha Gessen: Oh, that’s um…that’s a difficult question. I’m actually not finding hope in people talking about the future. I think there are people academia who are thinking about the future. I think that they’re not getting out into the public space. In fact I haven’t encountered them even though this is something that I’m thinking about and writing about.

Where I do find hope in sort of the immediate present is in some of the resistance. I think that the way that the Trump presidency has been unfolding in some surprising ways is in how it has galvanized civil society in a very broad way. The response to the travel ban demonstrated something very peculiar about this country. Which is that this country has the most robust civil society ever, and anywhere in the world. For some of the wrong reasons, I would argue. That’s a whole other topic.

But it’s there. And it can act and push institutions toward acting. And so that’s what we saw with the travel ban. We saw people coming out into the streets, through the street-level civil society all the way to professional civil society, which was the ACLU immediately filing suit. And then we saw courts acting in response to that pressure, both from the street and from the professional civil society. And so that is a kind of resilience that’s not based entirely in institutions, which are being decimated, but that is built into the society at this moment and is giving us a lot of lead time.

I think there’s a lot of reinvention going on in the media. I think it goes sort of on a parallel track with what’s probably unavoidable normalization. And the normalization is depressing but predictable. But the mobilization is actually pretty awesome. I mean, the way that we’re sort of this competition between the Times and The Washington Post of the kind that hasn’t happened in years or probably decades. The kind of collaboration which I think is even more exciting between different investigative outlets including different nonprofit investigative outlets. And we’re going to be seeing more sort of fruits of those efforts in a bit. So that’s actual honest-to-goodness reinvention. And that starts to to get us toward the future.

Audience 2: So, do you think that— You sort of talked about this contradiction of the competence required by conspiracy theory. Is it possible that that’s part of the appeal of conspiracies? That maybe there’s somebody that’s really much wiser than we think—

Gessen: Yes.

Audience 2: —in charge, that could have fleets of black helicopters and be manipulating the atmosphere. I mean, wouldn’t it be great if the government actually had some division that was that competent?

Gessen: Oh, absolutely. I mean, I think that’s a huge part of the appeal. Because to imagine that the world is run by incompetent, not terribly intelligent or just simply stupid uncurious men… Which as someone who you know, lives here now and who is a biographer of Putin I can tell you that’s what it is, right. And I think that part of the particular Russia conspiracy sort of subconsciously is that. That well, if we have a clown for a president, at least they have a competent former spy for president.

Unfortunate that’s not the case. He has a more control over his statements and emotions than Trump has. But in terms of his level of education and his level of curiosity? It’s roughly the same. And so Those are the two men who have their fingers on the nuclear button.

Audience 3: So I guess the answer to this might be the hard problem of critical thinking? But I just wanted to know like, engaging reality, that’s a very strong, profound statement. But what is the litmus test for that? Because you can kind of engage with a lot of people and hear their truths and understand that, and then sort of look at facts and such. But then creating a narrative that is based in reality, that can be a hard thing to do.

Gessen: Well, you’re right. Critical thinking is that. And I think the litmus test is feeling uncomfortable. I mean, I think that there’s… And I want to be very clear about this. There’s a lot to be said for being around like-minded people at a time like this. It saves your sanity. It is really important to go out and talk to people who do affirm your reality and who do affirm your sense of how bad things are or where the hope is or whatever.

But if that’s all you’re getting? Then you’re not actually engaging reality. And so you know, I think each of us has to set a level of discomfort for ourselves that is tolerable. Or maybe that’s just a little bit beyond tolerable. And that’s probably the level to aim for.

Audience 4 So Masha, I’m Nico. [sp?] I’m a big fan. And having read a lot of the essays you’ve been writing in the New York Review of Books but also the recent essay in Harper’s… But also the recent essay in Harper’s terrified me. Mostly because I’d heard you speak at a neighboring academic institution recently, and found you kinda calming in your sense that we had to be clear-eyed and not give into conspiracy thinking when looking at the current situation.

But the Harper’s essay on the Reichstag fire was like, really alarming and felt almost… I felt like it was driving me into conspiracy thinking, in a sense. And then I listened to you again today— I’m just struggling with the relationship between finding something alarming and feeling like there’s a great urgency to the moment, and how easily that feels like that tips in a way from clear-minded strategic thinking to conspiracy thinking.

Gessen: Right. So that’s um… I think you’re inviting me to summarize a 5,000 word essay in Harper’s in two words or less. But… Well, that’s the only way I can answer that question. So Harper’s asked me to write about the looming Reichstag fire, which I think is a trope that a lot of you have encountered if not all of you, which is that something is going to happen. There’s going to be a terrorist attack that Trump was going to use for an all-out political crackdown.

And the argument that I made is that that’s happened. It happened on 9/11. And a lot of the reason that we have Trump is because of what happened then and because we have existed in a state of emergency for sixteen years. Not just a legal state of emergency, although that’s also true, but a mental state of forever war, a mental state of mobilization, a mental state of exception. And to some extent a legal state of exception. Which is what a Reichstag fire is.

I wasn’t arguing for the conspiracy theory that attaches itself to a Reichstag fire because in fact, we don’t know if there was a conspiracy. And this brings me around to the bad joke. We don’t know that the Nazi party actually engineered the Reichstag fire. The preponderance of the evidence now seems to be that no, it was one young communist activist acting alone and the Nazi party took great advantage of that particular event.

So I don’t think, Nick, that it should take you down the road of conspiracy thinking. Should it alarm you? Yeah, it should totally alarm you. But I think being alarmed is a good state. I think we should stay alarmed certainly at least as long as this president is in power and probably longer.

Farai Chideya: The next person who’s coming up here also exemplifies the joy in the struggle. He took an incredible risk and pivoted his life by disclosing his status as an undocumented American. His project is Define American. He’s the founder and CEO of a nonprofit media advocacy organization that uses storytelling to humanize conversations around immigration, citizenship, and identity. Jose Antonio Vargas also won a Pulitzer Prize for reporting, while he was an undocumented journalist at a major news organization, on the Virginia Tech shooting in 2008.

Further Reference

Notes on this presentation by J. Nathan Matias at the Center for Civic Media blog