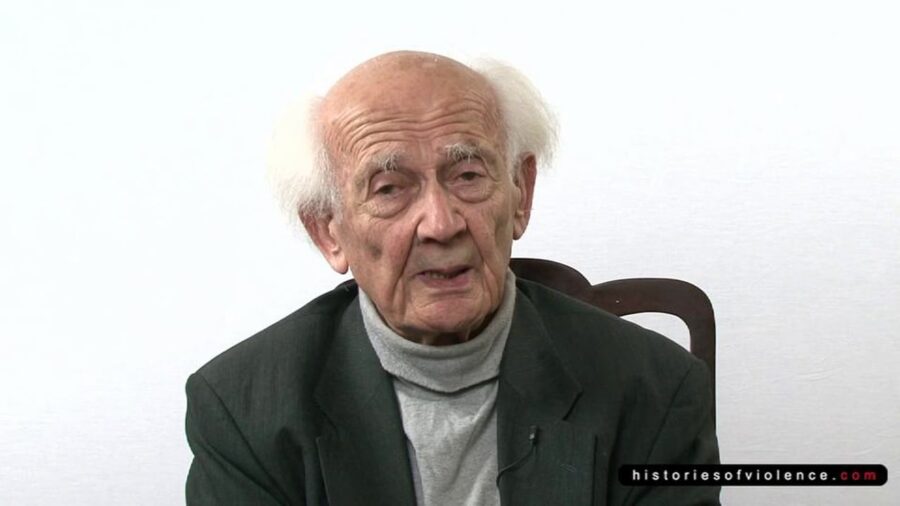

Zygmunt Bauman: Well, let’s imagine ourselves sitting on a plane, up there in the sky. And sitting very comfortably. Some of us are reading, some of us are drinking, some having a nap. Some play the computer games. Some simply anticipate the pleasures of the [indistinct] which will meet them after landing.

But suddenly, the news comes in that the very pleasant information coming on through the loudspeakers inside the cabin had been recorded quite a long time ago, so it is that there’s no one actually speaking to you. And then you discover that the pilot cabin is empty. And that the automatic pilot, probably leads you to some airport, but you learn as well that the airport in question is still in the planning stage, or rather on the drawing board, because the application hasn’t been submitted yet to the proper authorities.

It’s a frightening image, really. But it is roughly, in a nutshell, what our contemporary fears are like. They are fears of nothing being in control. Or first of all being ignorant of what is expecting us. Not really knowing what will happen next moment. And secondly, even if we do, we suspect that there’s very little we can do about it to stop the danger and to get out of the trouble.

No one is in control. That is the major source of contemporary fear. The fears are scattered. The fears are diffused. We can’t pinpoint the sources wherefrom they are coming. They seem to be ubiquitous. They seem to apply as much over private life as the life in common, the social life, all sorts of things may happen. It could be a tsunami. It could be Hurricane Katrina. It could be another earthquake. It could be sudden closing up of the factory in which you worked for twenty years. Or a hostile merger between two offices and you are losing your job. It may be collapse of the stock exchange and you’re losing your old-age pension and the savings you made for many many years. It could be another terrorist attack. It could be sudden street riots and [indistinct] and your shop is destroyed and burned. Your car is stolen or burned. And so on.

In other words, it seems that we are living on quicksand. Every movement which you want to make to stabilize our position may have quite the opposite consequences, like in quicksand. You may sink even deeper than before. And [it is] precisely because this fear, this contemporary fear, is so poorly located, I would say unpinpointable, that it is so frightening.

The question is why it is so. Wherefrom this feeling of absence of control? We are not in control, but not just that we are not in control. No one seems to be in control. Things seem to be happening at random, surprising, taking you unprepared. The question is wherefrom it comes.

Well I suggest to you that there is one essential reason from which other reasons are derivative. This one reason is what I would call the separation, coming very close to divorce, between power and politics. Power is the ability to have things done. And politics is the ability to decide which things are to be done.

Now, both abilities—the power and the politics—were until quite recently, until less than half a century ago, united in one place. That place was called nation-states. State government has both. It has power to do things, and the political institutions to decide which things are to be done. There were of course political right, political left, as always, but both sides of the political spectrum agreed on one point. That if we win, if our concept of what is to be done, is on the top, then we know who will do it. Because the state has power to do it.

It was never a full truth, but in a way it was a reasonable expectation, that if politics is decided then power is able to put it in operation. It’s no longer the case, because power has evaporated from the level of the nation-state up there into the cyberspace, or as Manuel Castells calls it, the “space of flows.” But the politics remained where it was for a number of centuries already. Namely, on the local level. It is still as local as before. There is nothing to control the power which liberated itself from political control and emigrated into the space of flows.

Finances, capitals, the trade, information, terrorism, criminality, weapon trade, the drug traffic. Everything which ignores the boundaries of national sovereignty, which ignores and is free to ignore and be unpunished for doing that. Ignores the local customs, local preferences, the will of [indistinct] and so on, that is already global. But the powers which could eventually control them are still local. And therefore there’s a big gap, growing hiatus, between the ability to do things and the ability to decide, to coerce, the powerful agencies to do what needs to be done.