Richard Sennett: The title of my talk, or the presentation, is “The Stupefying Smart City.” And it might seem to you that I’m therefore going to give you a kind of anti-technology talk. But that’s not the case. What I’m worried about is that with the technological tools that we have today, as in the past, our first use of them is the least inventive that we can make. And the issue is how urbanists can actually use these new tools well rather than use them in a way which is harmful.

As I say in my paper, this has old history in the history technology—the invention of the scalpel took nearly a century for people to figure out how to use this supersharp knife in order to do better surgery. And I think the same thing is true for the technological tools that we have at our disposal for the smart city. At present, there are temptations to use them in ways which are stupefying to the populace, in which the tool substitutes for the judgment of the urbanite. And that I think is something that we have to counter and that we can counter. That we’re beginning to get a more sophisticated sense of how these tools could be used, but its a policy choice. And I’ll try and lay that out to you.

What I’d like to add to what I’ve written in the newspaper is the following. You could think in a way of the issue here of what this technology can take away from people’s capacity to reason, to feel, to make sense of complexity, by posing the question “Do you need a street to have street smarts?” And my answer to that question is yes. That is, to be a sophisticated, competent urbanite, you need a street. And I’d like to make that a little more technically clear to you, what that means.

In social psychology now, there have been studies for the last ten years about the ways in which people acquire an ability to think and feel—both together—about complexity. There’s studies of transitions from adolescence into adulthood. And they focused on the ways in which adults become adult by being able to deal with complexity. And these studies have focused on three capacities.

One is the toleration of ambiguity as a condition of adult cognition. The second is the ability to pursue incomplete action. That is, to bring something forward, to act on it even though the results are say 80% rather than 100%, or 51%, or even 30% of what you intended to accomplish. And the third form of this adult cognition is what’s called dialogics, which is the ability to listen to what somebody means behind the words that they use. And it’s a real advance in understanding the sort of higher levels of dealing with complexity that human beings can acquire as adults.

What the city does to these three forms of cognition about complexity is propose that you can learn how to tolerate ambiguity, to pursue incomplete action, or to practice dialogics with strangers. That is that strangers will stimulate you to practice these forms of cognition (and as I say, they’re both rational and emotional) more than being with people who are very familiar to you. So that there’s in principle a kind of— On the cultural/psychological side, there’s an intersection between the social condition of the city, potentially, and the process of becoming a sophisticated adult.

Now, here’s where the story I want to tell you enters in. Because we can use technology to disable these forms of learning complexity. And in my paper I’ve shown a couple of examples of how this can happen. Of a use of technology that makes people more stupid—and that’s not quite a word I like, but it’s a wonderful title. But in which something where people are not stimulated to deal with complexity in all of its forms because of the way in which we’re thinking technologically.

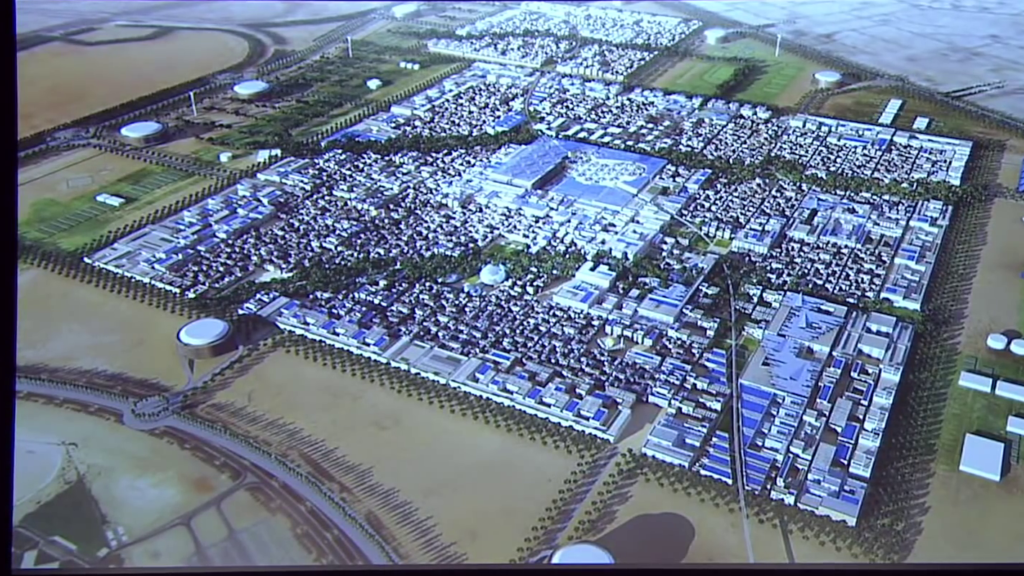

Here for instance is Masdar, in the United Arab Republic. It’s a city planned with a tight fit between form and function. It’s a very Fordist city in that way. For each function there’s a place, and a form. And what that means is there’s not much stimulation to think about difficulty. Or to try and make sense of the relation between where and what. It’s all been done in advance.

Similarly, you can see here how it works. It’s something that is contained within itself. There are no fuzzy edges here— (I’m sorry, I don’t want go back to the talk that Ricky Burdette has accused me of being very philosophical about.) But this is a boundary rather than a border. That is, the edges of this big giant building are the edges of where settlement ends. There’s no periphery, there’s no ambiguity in the space.

And the space itself is something which is very directional in its social logic. You know exactly what’s happening in each of the spaces by the kind of architecture that’s made for it. It’s a very glitzy looking space, but it’s a space that requires no interpretation.

Now, this… Masdar, extremely expensive. It’s an experiment, as Saskia Sassen has pointed out, in how far you can push technology. And perhaps only the UAR could afford it. But it’s an experiment in Fordism. And this kind of environmental Fordism I want to argue to you is a way of stupefying people. Of depriving them of the spaces in which they develop those three street smarts of tolerance of ambiguity, the pursuit of incomplete action, and dialogics.

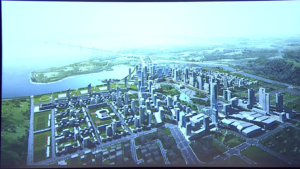

Now, here is Songdo. It’s another smart city. It looks beautiful in a way. But when you look here you see something that I think for urbanists is a very very important problem. There’s no horizontal value in this space. I don’t mean simply that there aren’t streets, but that the notion of horizontality has been removed from the space. It’s a deprivation— You don’t go out. Here everything’s contained in the building.

Some of that has to do with the climate of South Korea, which is harsh. But Koreans typically have overcome their climate, and use the horizontal with basements. They’ve been very clever about using belowground as a kind of horizontal. And the horizontal is a way of extending out encounters with other people. This is a space, in my view, of deprivation, because it has no streets. You can’t develop street smarts when you’ve taken away half of the visual vector of what people need for their experience of other people.

These buildings each have a function, and people are stacked up in them, again according to the Fordist principle of you go where you go where you belong, you are never where you don’t belong.

Here’s another part of it built up. You can see there’s no meaningful street here for human beings.

By contrast—and I just bring this in, this is Third Avenue. This is a space in Third Avenue where the building typology, vertically, is as monotonous as this. [slide not shown] I’m showing you an older building. But the vertical typology is terrible. But, at the ground plane the idea is that while up is pretty much uniform, the ground plane is something that’s disorderly, confused, ambiguous, incomplete, that needs to be read and needs to be interpreted. And my argument to you as urbanists is that what we’ve got to do in using this technology is figure out ways in which we do not abolish the horizontal ground dimension. It’s the dimension of complexity, such as we know it today.

Songdo and Masdar represent I think ways of simplifying the city even with its enormous technical complexity, simplifying the space of the city, and making people unable to access this kind of mature development along these three axes that I’ve indicated.

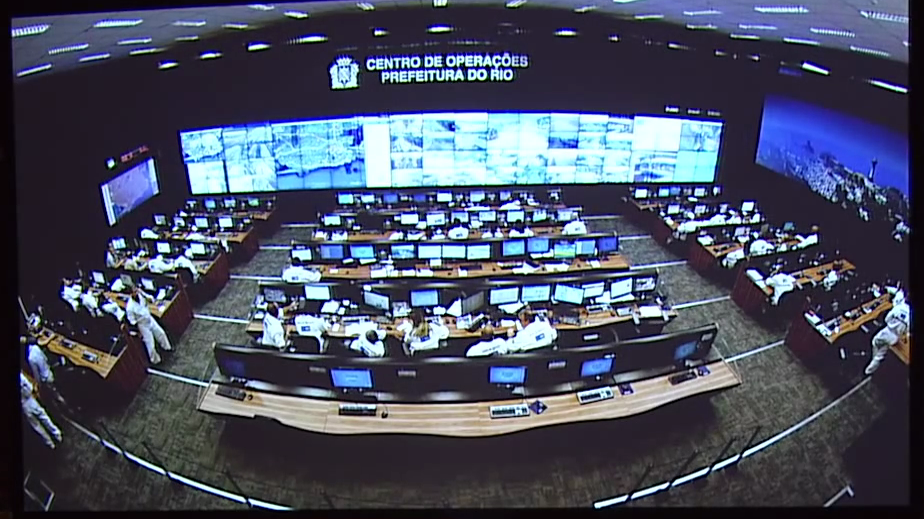

I just as a counter to this want to say something about Rio de Janeiro, which has used the information-gathering capacity (this is a wonderful project pursued By IBM and Cisco) to do coordination of what’s happening in the city, rather than a kind of preplanning of what should happen. This is a completely different a model of technological use. One in which the technology deals with complexity on the ground rather than tries to preclude it through overplanning and overdesign. This is sometimes known as “the headache room,” and you can understand all those screens represent traffic blocks, points where people have to get through, where ambulances have to get through, and so on. In other words they represent spaces in the city to which the technology is reactive, trying to enable what’s happening on the ground.

And to me this seems like a much more useful tool in thinking about how to take technology forward than thinking about the central processing systems that we now have as prescriptive. This is coordinative rather than prescriptive use of technology. And I think that’s the way forward for us as urbanists, that we have to think more in that line than about how to make the city resemble a well-oiled, well-functioning machine. If we do that, we take away as it were the genius of the city that makes people competent urbanites. Thank you very much.

Further Reference

“The Stupefying Smart City” essay by Richard Sennet [different from this presentation] in the Urban Age: Electric City conference newspaper

Citations

- Jak i po co wspierać kulturę miejskiej pomysłowości? Wnioski z ewaluacji mechanizmów „Pomysłowy Żoliborz” i „DziałaMY! Wawer” [HOW AND WHY TO SUPPORT A CULTURE OF URBAN RESOURCEFULNESS? CONCLUSIONS FROM THE EVALUATION OF THE ‘POMYSŁOWY ŻOLIBORZ’ AND ‘DziałaMY! WAWER’ MECHANISMS]

- Towards an Understanding of Enablement in Online Non-delivery Fraud

- The City: An Interdisciplinary Introduction to Urban Studies

- The Algorithmic Society: Technology, Power, and Knowledge, ” Five smart city futures”

- ОРГАНИЗАЦИЯ СОЦИАЛЬНОГО ПРОСТРАНСТВА СОВРЕМЕННЫХ ГОРОДОВ В СВЕТЕ КОНЦЕПЦИЙ “ОТКРЫТОГО” И “УМНОГО” ГОРОДА

- The palace is no fun — Disparate and diffuse ideological backgrounds of technologically augmented architectures