Golan Levin: Our final presenter this evening is the Director of the Clinic for Open Source Arts, Chris Coleman. He and his institution at the University of Denver have been a partner of the STUDIO in organizing this residency. Chris Coleman is also an artist and professor at the University of Denver. He was born in West Virginia, United States, and he received his MFA from SUNY Buffalo, New York. His working includes sculptures, videos, creative coding, and interactive installations. Coleman has had his work in exhibitions and festivals in more than twenty countries, including Brazil, Argentina, Singapore, Finland, and the United Arab Emirates, Italy, Germany, France, China, the UK, Latvia, and across North America. Chris is Director of the Clinic for Open Source Arts at the University of Denver, as I mentioned a partner organization for our residency program, which works to explore, support, and celebrate local and global efforts to make free and open source tools that allow people to be creative with digital technology. Chris Coleman.

Chris Coleman: Hello. Thank you Golan. I appreciate that. Alright I’m gonna share my screen here.

So I’m gonna talk a little bit today…I’m gonna try and frame things around the idea of digital citizenship. And I used lower case here because I don’t always love the term “citizen” and it’s been misused a lot over time. But I think there’s something here, and I was very much inspired by some of the earlier speakers this week and their thinking about the roles we play and the ways that we work together to accomplish these bigger things.

https://vimeo.com/3901283

So, I’ll start here. This is an earlier animation called The Magnitude of the Continental Divides. I think it gives maybe a starting place in some of my thinking about the big questions that I’m trying to tackle with my artwork. This particular animation was drawn from a lot of illustrations from boy scout manuals and other sort of documents of indoctrination, and maybe empowerment as well, from our American culture—or white American culture—and tries to recontextualize them and combine them with a lot of imagery from terrorism readiness brochures that were handed out around 9/11.

This particular piece was shown in Times Square, which was a really great honor. But it’s really thinking a lot about the nature of the way that we treat other people. How we sort of convert people into being an other, or sort of being separate from who we are. And how we sort of reconcile the notion of borders, and how we allow those things to sort of separate us.

So these big topics, this notion of border, which is a construct of these completely invisible lines that we draw all over the landscape in order to try and say that somebody on this side of the line is different from somebody on this side of the line…which again is completely false but it’s a sort of construct that we all agree to abide by. So that’s like a containing action. So borders are meant to sort of define and restrain us. And simultaneously we operate on a global capitalist sort of economic society that basically suggests that there is nothing but endless growth in our future. We will always expand, we can always keep growing, we’ll never run out of anything. And I’m really interested in the sort of conflict of these two ideas, but also how they’re both used at the same time to sort of put into place various systems of control and manipulation on top of us.

And so out of these two things comes the sense of othering and a sort of selfishness that’s embedded in those ideas of like okay, what’s within this box is mine, this imaginary box. You know, property ownership, all of these ideas about how things are contained. And it sort of neglects the sort of bigger picture ideas that I’m really interested in, and I think is at the heart of the way we live in digital spaces and specifically open source processes. Which is like, how do we work together to create something bigger than what we can do apart, or alone? And so you have to kind of push past selfishness. And you have to accept that we’re actually all operating in a similar layer. And that borders are kind of irrelevant. And that there’s something beautiful about the moment the Internet began, there was something beautiful in those ideas of this. This sort of removal of these sort of physical barriers.

And so this was some of my big question is like, as we continue to become more and more digital prime— (Thank you David Rudnick for introducing this vocabulary to me recently.) As we become more digital prime, what is it that we take with us in terms of values and processes? And it’s been quite frankly really scary to see how quickly a lot of the sort of capitalist processes, the notion of exclusivity, have been sort of rushing into the vacuum of the digital spaces and trying to make sure that they secure a new place, a new way of sort of separating us from each other in this new world. So yeah, I’m trying to explore some of that with my work.

And that brings me to a body of work called Secure Shell Copy, where I’ve been scanning hundreds of people as I travel the world as an artist and turning these into various kinds of portraits, and thinking about the 3D scan as a kind of photograph with an infinitely-thin shell, a sort of surface that never has any depth and then can be manipulated by digital material.

And so I think in many ways these are not unlike the kind of versions of ourselves that we present onto social media spaces like Instagram, and Facebook, and all of those other places. So that these sort of fragmented, false visages represent us in this digital world.

And that became a magazine which you can actually get online if you’d like, a series of portraits, and some animations as well. And this is some work that’s ongoing. But thinking about what does it look like to have a body that can accommodate the near-endless fluctuation of our digitalness and the ways that digitalness sort of represents us in this space.

https://vimeo.com/135783440

I think maybe in a more positive note, I’ve been working on a project since 2011 with Laleh Mehran. And she’s my wife and a fellow artist, and also a CMU alumni by the way. And we worked on a project called W3FI. [pronounced “we-fi”] It’s a sort of rewriting of the notion of wifi, removing the “I,” the “me” from it and turning it into a “we” or a collective notion. So rethinking the sort of invisible network that we all used to connect the Internet. What if it was less about sort of how do I get on the Internet and what if it’s more about how we exist on the Internet? And W3FI was built on the principles of sort of the Buddhist path to enlightenment, thinking about going from the acknowledgement of the self and your role in the world to the we, to understanding how we all exist as these separate cells but also in this collective space. We exist together, and finally wefi as a sort of way of acting positively on and with each other, understanding that we can all cause harm to each other’s digital selves significantly easier than we used to be able to each other’s physical selves.

And so this project started in 2011 really exploring these issues. It’s a little bit out of date these days. You can also see here there’s a lot of data visualization involving how people use data over time in their cities, cellphone towers, wifi routers. Just gathering lots of bits of information about each city that it goes to. And it’s traveled all over the world. Which has been a really sort of beautiful experience, to travel with a piece of work like this.

https://vimeo.com/158831509

And then another piece done with Laleh Mehran is called Unclaimed. Unclaimed is an interactive work where you can blow across this city, and as you blow across the city your breath’s sort of captured in light in a sort of fluid simulation underneath the city itself.

And we’re interested in how all of these breaths sort of mix and flow against each other. The idea that we’re all participating in this sort of strange layer of atmosphere that is actually considered unclaimed space. It’s one of the sort of remaining global commons, I would argue, where everything above a certain level above your house to where the FAA regulates, is this sort of nebulous land, or nebulous space. And it’s actually like, it’s air. It’s air that we all share, we breathe. It’s air that’s been blown here from Brazil after coming around through China and going across Europe. It’s like how do we take more responsibility for the commons of this airspace.

And so this piece actually takes all of your breath as seen on the table and reproduces it using a series of several hundred fans underneath this giant sheet of plastic, creating these huge waves and airforms, turning your small breath into a huge effect across the entire ceiling of the space. So again sort of like how to link those notions of responsibility and citizenship from the sort of personal to the collective was the intention of a work like this.

So these are some of the ways that my artwork actually tackles the notion of citizenship and the roles that I play. I’m inspired by both the Critical Engineering Manifesto and Golan’s lecture on being an arts engineer. And I consider myself a critical arts engineer. And part of my sort of task doing such things was actually that I made this tool called Maxuino, originally from teaching my class. I just wanted to help my students work more quickly to have an Arduino and have Max and be able to make cool stuff happen. And so developing a tool called Maxuino, then Ali Momeni came on board to help me with a lot of the GUI stuff. He’s a Max GUI master.

But really at its core it was a sort of simplified way for Max people to start doing physical computing tasks. And so starting that in I believe 2009… It’s a very old tool at this point. Goodness. Maybe it was later. Now I’ve got to look it up. Alright, maybe it was in 2009; I’m not sure. I started maintaining this open source tool and really starting to understand the challenges of what it means to upkeep the tool, to promote a tool, to deal with requests from users, to make educational resources available, to write documentation so other people can understand it. These were all sort of processes that I learned the hard way by having a tool like this.

And so you know, it’s funny. Like even now, I went to grab a couple more screenshots from the web site…and it’s down. So I have work to do when I get off this particular talk.

So that has led me over time to develop COSA, the Clinic for Open Source Arts. And COSA is a brand new sort of initiative that stems out of sort of my earlier interest in what does it look like to have an institution like mine, a private university for the public good, as we call ourselves at the University of Denver. What does it look like for us to start really engaging in supporting the tools that we’re using in our classrooms.

![[Slide area of broadcast shows a blank gray screen]](http://opentranscripts.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/ossta-spring-2021-chris-coleman-030-1024x578.png)

And what it looked like was to start doing kind of events and things. And really this is all modeled off of the work of other people. Having watched Golan Levin and the STUDIO for Creative Inquiry for years bring in open source contributors, doing code sprints, creating various activities so that the tools that artists need are well-supported in the space. I only try and follow those footsteps, and I think the sort of thought behind COSA and the sense towards focusing on community and focusing on sustainability and health, those have all been really driven by the model set by Lauren McCarthy and her work on p5.js, who really started to show I think in many ways a sort of new model for what a healthy community could look like, and what are all the things that need to go into making a project like that really welcoming and supported and supportable.

So we do a lot of things. As I said, we’re focused on health and thinking about lots of aspects of that. We’ve supported a lot of projects recently, including really wonderful things like ml5, which we heard about last night. We’ve actually supported CARL, which you just heard about, from Char and Chirag. The PEmbroider project out of the STUDIO for Creative Inquiry. You might have heard last night Bomani was talking about the Out of the Black Box project. So these have been a lot of the sort of grant processes that we’ve been going through.

And then we have also been doing various events. The work actually began in 2015, when we hosted the developers of Processing to do Processing version 3. They actually sort of finalized that release there in our spaces, followed up by an education summit for openFrameworks in 2016, doing the Processing Community Day here in Denver and engaging a hundred people in our local community, which was really fantastic. And going to other conferences. We actually just did an openFrameworks contributor’s conference in the fall of 2019, having some long and sort of overdue conversations about what the openFrameworks community needs that’s bigger than just the code itself. And so you know, we’ve been really interested in those ongoing conversations.

Oh. And you all didn’t see any of that. That’s awesome. [laughs] That sucks. Was on a roll. Alright.

So I was showing you some of the great things that we do. You can go and read about them at the Clinic for Open Source Arts web site, which is clinicopensourcearts.org. That was embarrassing. But we’ll move on. And we also have the supported projects that I was talking about, where you can read more about things like CARL, and the Feminist Data Sets, and Netnet.studio, and lots of other really great tools, some of which are already included in this OSSTA event, and some of them will be unfamiliar to you.

So. All of that said, I’m going to switch back to the presentation.

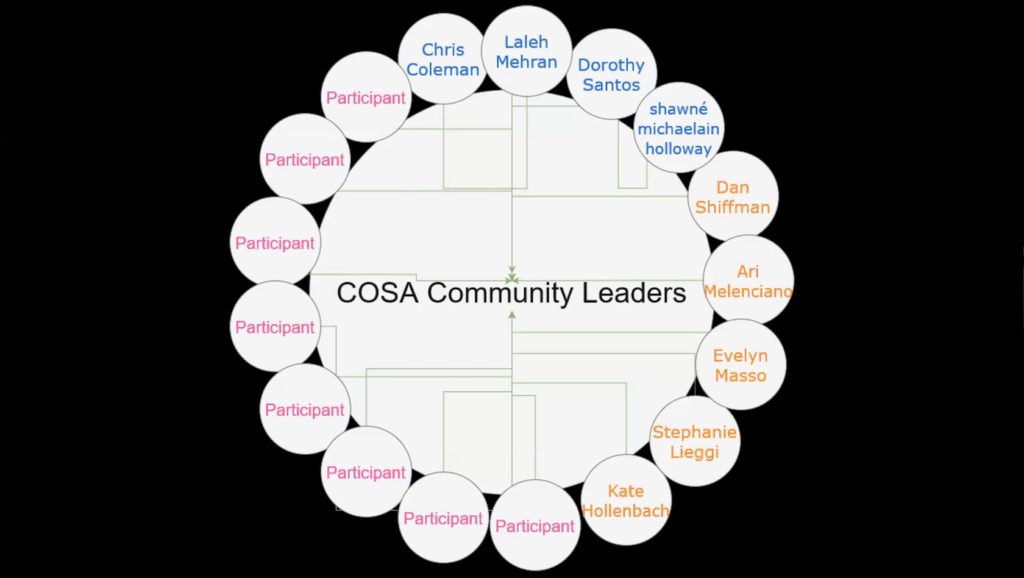

So to bring it to the here and now, COSA is just now finishing up a program called the COSA Community Leaders. And the COSA Community Leaders program was essentially an effort to spend about ten weeks, eleven weeks, where he had every-other-week sessions talking about various topics related to what it means to actually lead a community around open source. And spending a week thinking about values, spending a week thinking about branding and outreach, spending a week thinking about documentation and fundraising. All of these different topics. Going into into each of them with pretty intense detail. And then really trying to just create a community of people who are leading in the space. We have eight participants. We had five people who were serving as mentors and instructors, and a four-person steering committee team. (All listed here.) And so we actually are going to have continued check-ins. This is also funded by the NEA, likes the OSSTA residency.

We have check-ins for the six month and twelve months, as we continue to work with everybody. A write-up is forthcoming on this. But I think it was a really beautiful opportunity to try and say like, what does it look like to start to support and develop leaders in this space who don’t have to learn everything through the school of hard knocks and are maybe more cultivated and sort of welcomed into the space? And to already have a built network of other people who are trying to do this kind of leadership, so that they know who they can go to to ask questions and just sort of say like “Hey, I want to put on an event. Who has a great survey that helps me understand my participants as we onboard them into the event?” These are really simple things that a lot of people in the community have and shouldn’t have to be reinvented, but if you don’t know who to ask then that becomes the problem. So, trying to develop these networks.

Next up will be the COSA Community Contributors program, where we’re gonna look at what it means to go one step down in the sort of chain and train contributors. What does it mean to get people who’re ready to contribute but don’t really know how to engage, are not familiar with all the processes? Not just technical but in terms of community as well. Like how do we make sure that they’re ready to engage and do that in a healthy way, and a way that feels sustainable to them personally, and helps the project move forward. And so that’ll be our next stage coming up this fall. If there are those of you who are interested in such an idea, and maybe even want to be a participant in learning to be a contributor or maybe even learning to be a better contributor, you should reach out.

And then in the long term we’re really thinking quite a bit about what it means to be a clinic, and the notion of how do we go from just being a clinic that’s thinking and watching and listening, which is kind of the stage we’ve been at, to starting to diagnose and help open source tool projects understand what their issues are and have experts engaged in a sort of analysis and providing that feedback back to a community. And then how do we actually provide them with care? And not just one-off care but care that could significantly alter and help them shift from one modality to another.

And that modality might be how to go from a one-person project to a three-person project. It might be how to go from a big project to something that goes into hibernation or is handed off to somebody new. So there’s all sorts of different roles and different ways of thinking about sustainability with these tools. And we’re trying to address a lot of them.

And we’re doing that with the help of grants from the National Endowment for the Arts. The Knight Foundation provided us with a significant grant to help get the Clinic for Open Source Arts started. And then also the Mellon Foundation providing funding at my university that helped with a number of different opportunities as well.

And so finally, if you want to read more about the Clinic for Open Source Arts, it’s at clinicopensourcearts.org. Or you can just email me at cosa@du.edu. And then all of my stuff is under “digitalcoleman.” That’s my moniker everywhere on the Internet, if you need more information or want to look at my artworks in full. Alright, thanks.

Golan Levin: Chris, thank you so much. That was wonderful. I really appreciate your presentation. I’m so grateful to you for sort of taking on this huge initiative to support open source tools for the arts. It’s not a small task. I mean, as you pointed out we’ve been doing this for some time at the STUDIO, but in a really sort of…kind of not particularly…organized way, sort of a haphazard way of okay we got a grant, let’s support a whole bunch of toolkits. Or let’s have a contributors meeting for this particular toolkit that we care about. But your way of thinking about this in a much more surgical way; literally like, we’re gonna diagnose, we’re gonna like…“Oh I see what your problem is, you’re at this stage of the open source catastrophe.” So figuring out how to help tools, that is great. And it’s been wonderful to have you as a partner for this residency that we’ve done.

I guess one question I have is how do you justify this within the University of Denver. As we know from the Open Source Software for the Arts convening that we had a couple years ago and the report that we made from it, universities are a major source of support for these open source software toolkits for the arts. NYU, where Dan Shiffman has been has been a big supporter, putting money directly into ml5.js for example. UCLA has a fantastic department with Casey Reas and Lauren McCarthy, which is really an epicenter of thinking in terms of sketching with code.

But each of these different organizations needs to have kind of their own way of internally justifying how and why they support things the way that they’re doing. Maybe it’s because it’s faculty research, for example. In our case here at the STUDIO it’s ultimately sort of student-driven. We bring these guests to campus as a way of providing apprenticeship opportunities, and we’ve had some student apprentices working with the OSSTA residents this spring. How do you justify within your university sort forming a mini institution like the Clinic for Open Source Arts, which might or probably will be a multi-year effort?

Chris Coleman: Yeah. My university’s still trying to reconcile with the thing I’ve made, I think in some ways. Part of it really started out as the idea of like okay, the university’s actually having a really hard time helping us give money directly to these projects. And so maybe an alternative methodology is actually to use that money to create activities and create processes that happen here at the university which then benefit the university in addition to benefiting the projects themselves. So I think that was sort of a starting place? I think in the longer term, I’ve also been making sort of long-term arguments for my own research and trying to argue…especially in the arts schools, you can imagine trying to convince them that yes, me making software that is free and open source to the world is just as important as exhibiting in a white box gallery.

So you know, I think it’s been sort of many-fold. I think the university is still really interested, and I think in particular because we’re in the arts they’re really excited with the notion that the arts and humanities are actually also doing computing technology stuff and open source stuff. And so we’re sort of twice as valuable to the dean of the arts, humanities, social sciences, because he sees it as a playground for his people.

Levin: So one of the sort of missed opportunities for our current residency, we’re very grateful to support from the National Endowment for the Arts to enable the residency that brought the speakers that we’re all hearing from this week. But one of the interesting constraints that we had in receiving funds from the national government, particularly when we received the grant because it was in the previous presidential administration, was that we were strongly limited to supporting artists who’re working here in the United States. And you know, I see like Olivia Jack in the YouTube stream right now and I’m like wow, yeah. I mean, there’s so many people working on amazing toolkits that we really wanted to support like Olivia or Karsten Schmidt, also known as Toxi, over in the UK and Germany. So many great people working in England. Nathalie Lawhead in their presentation a few days ago made a list of tiny tools that happen to be some of their favorites, and so many that are being made in Europe.

Coleman: Right.

Levin: And I wonder, do you face similar limitations in supporting only toolkits that are happening in the United States, or can you support some things that’re going to be worldwide?

Coleman: Yeah. I mean you know, I’ve been fortunate with the Knight funding and some of the other funding, there’s a lot more flexibility. But you’re right, the NEA part of my funding has had the same sort of limitations. I’m hoping we can continue to push against that. Although I understand the government wants to pay US people to do stuff with our tax money. But yeah, I mean you know. As you know, the process of constantly writing grants and finding funding, and then convincing the university and other institutions to support this work, there has to be a strong belief in like, we’re in this together as a global entity. It doesn’t stop at the US border who uses these tools and who makes the tools. And like, the things used in our classroom are made in other parts of the world and that’s the beautiful thing about this, right. So, reinforcing that with the bureaucracy is a big part of the job.

Levin: Thanks for doing this work, Chris. This is really great to have you as a partner.

Coleman: Yeah, thank you for putting it all on.