Golan Levin: Welcome back everyone to Shall Make, Shall Be. Our next speaker is Shawn Pierre, whose project deals with the Fifth Amendment.

Shawn Pierre is a Visiting Assistant Arts Professor at the NYU Game Center and game designer working to combine new forms of play with different types of media. His work includes voice-controlled adventure games, social deduction SMS games, and physical games where players capture others in nets. In the past Shawn has created and worked on crowd-based interactive activities including installments at Graceland, as well as games for major sporting events. As a member and Project Director of Philly Game Mechanics, Shawn works to build a community where local creators meet new people and share their creative work.

Friends, please welcome Shawn Pierre.

Shawn Pierre: Hi, everybody. Once again, my name is Shawn Pierre. Yes, I am a Visiting Assistant Arts Professor at NYU. So I’m hanging out at the NYU Game Center. And as you just said, I also help and organize a group called Philly Game Mechanics, which as the name suggestions is based out of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. And our goal is to foster the development scene in Philadelphia, supporting both hobbyists and independent developers by having meetups, game jams, social gatherings. Which you know, most of them virtual. I am also a game designer, of course working on a bunch of games: digital, physical, tabletop. And outside of games I like to make bread every once in a while.

But back to games. I mentioned I’m a bit all over the place with the games I make, so just a bit about me. I’m making a lot of digital games now, but I also make live interaction games. And I don’t have any photos of this because normally when I play the game, I’m running things from a computer. But I had a version of Werewolf called Urban Werewolf where I ran an event called Come Out and Play in 2015 in Brooklyn. It’s a version of the game Werewolf, and it’s played via SMS with an automated moderator.

So I’ll talk a bit more about how it works. When the game starts, you receive a phone call letting you know that you are a villager or a werewolf, while everyone else receives a text message with a role and a four-digit code. So you can be the florist, you could be the doctor, you could be the carpenter. And your code could be “3483.” During the day phase, you receive a job. And the job was to find someone else. So if I was a florist I would have to find the carpenter. I would get their four-digit code and text it to the system. So people would be going around asking each other for their secret codes, texting them to the system. If I text once correctly, that counts as one task done. Everyone as a group has to complete twelve or else a villager is randomly eliminated.

And then of course during the night phase you have a person who is the wolf, who we said discretely send a text message with someone’s code to the “moderator.” Then the day phase comes about, that person’s eliminated. The community makes their accusations, guesses, etc. Then everyone sends the code for the person they want to eliminate, as with traditional Werewolf. And just like with traditional Werewolf, the game ends when the werewolf gets eliminated or the number of wolves and villagers are equal.

Another thing that I worked on in the past, which kind of combined some real space and digital space, is a game I worked on for the digital component of the Philadelphia Fringe Festival. I made a game called Known Sender. And it was a narrative game based in Twine. Twine is a tool that is primarily used to make narrative experiences. So with this game, you start off home alone one evening watching TV and checking your email. And then eventually you get an email from a friend who asks your for your phone number. But your real-life cell phone number.

So, you enter your number, you send it to your friend. And after that the game becomes a slight…horror-mystery style game?, where you’re receiving text messages and phone calls. And the only way to advance on-screen is to respond to these text messages and calls. So you’re partially playing on your computer, but you’re also playing on your phone using basic SMS.

So yeah, my work, it’s kind of a bit all over the place. For this exhibition, I am working on a game called “___ vs ___”. [pronounced “blank versus blank”] It’s called ___ vs ___ because when people play, I want them to add their names to the blank spots—they’re actual blanks not a wordplay. So, if I were playing a friend named Amber, the name of the game would be instead of ___ vs ___, it’s “Amber vs Shawn.” Each time you play, it becomes a unique case special to you and the person you’re playing with.

So once again, I was tasked with making something based on the Fifth Amendment. And as with a bunch of other amendments, it’s tied up with a bunch of different things.

So the Fifth Amendment is,

No person shall be held to answer for a capital, or otherwise infamous crime, unless on a presentment or indictment of a Grand Jury, except in cases arising in the land or naval forces, or in the Militia, when in actual service in time of War or public danger; nor shall any person be subject for the same offence to be twice put in jeopardy of life or limb; nor shall be compelled in any criminal case to be a witness against himself, nor be deprived of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law; nor shall private property be taken for public use, without just compensation.

Okay. So I think to properly understand where I’m working with the game we need to take a look at all the pieces of the Fifth Amendment. Probably the most famous part of it is the part about self-incrimination. This is where you see or hear people saying, “I plead the Fifth,” in movies or in TV shows, or with your friends for fun, right? They’re referring to this amendment. It does protect you from incriminating yourself through testimony. And tied up all in there, you have something called a Miranda warning, which is also pretty popular. This is when you hear someone say you know, “Read ’em their rights,” and then someone says, “You have the right to remain silent,” or, “Anything you say can be used against you a court of law.” Those are your Miranda warnings or Miranda rights.

Then after that, we also have double jeopardy. Not as much fun as the game show, but if you went through the whole process where you were convicted or acquitted for a crime, you can’t be prosecuted for a second time. There’s a whole bunch of if, ands, or buts in there but that’s the general thing.

And then there are some less popular parts of it. One referring to the grand jury, and the other one related to due process, and eminent domain. For the grand jury and due process, basically the government needs to act according to the legal rules. They can’t violate any proceedings and basically need to be fair.

And then the Takings Clause, which is the whole eminent domain. The government can’t take private property without just compensation. The weird thing here probably, what does “just compensation” mean? But you know, I’m not a lawyer so don’t ask me to go into more detail about what counts as property and what is just and whether you could give someone like a big bag of cash.

So, I wanted to try and make my game be as proper as possible, or use the parts of the amendment as closely as possible. Most of us were able to speak to a lawyer, actually, about our specific amendments and how they were used in the past, and what would happen maybe in specific cases. I had a very difficult time finding a case that involved all the pieces of the Fifth Amendment. And trying to get all of this into the game felt a bit unnatural. But trying to make the game fit the legal system…yeah, that was taking away from some of the fun of the game.

So like I said, there are a bunch of moving parts in this amendment, like I’m sure with everyone else. But for my game I’m focusing on double jeopardy, incrimination, and the Miranda warnings. So this is how the game works, and I’ll show you some images of that.

So, it’s a two-player game. One person starts as the suspect, the other player’s the investigator. The goal for the investigator is to figure out the crime that the suspect committed from a list of crimes. The suspect, their job is to get the investigator to pick the wrong crime, a crime that they already committed. One they’ve already been through the whole legal system for. If the investigator picks the wrong crime the game is over because of the Double Jeopardy Clause and the suspect wins. The suspect loses if the investigator picks the correct crime.

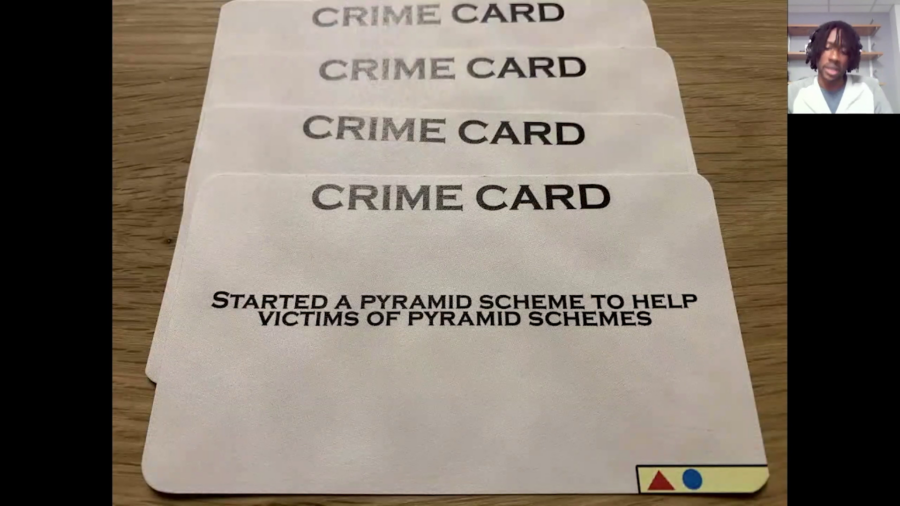

So, a bunch of crimes are placed on a table face-up, and the suspect picks two crimes: one to be the double jeopardy crime, and one to be the real crime. After they pick those, they write them down on a piece of paper and then put that inside an envelope, and they put that aside to be looked at later on. These are the crime cards and this is the envelope that everything goes in.

After that, the two players draw cards to decide on categories, and information about each category. Both players know what categories are chosen, but only the suspect knows the answers to these specific categories. All of these cards are placed in the special suspect folder, which only the suspect can use. There are a bunch of slots in the folder. It’s confidential, so I can’t open it, I’m sorry. This is information that’s all about the suspect. So we have specific categories for favorite movie genre, and hometown, and favorite hobby. And there are also cards that don’t have specific answers. So you can have categories like oldest possession, or least-favorite gift, or last item held. So for these sections, the less specific ones, the answers are all nouns like “telephone” or a water bottle. Both of those can fit the category of “last item held.” All these cards are related to the crimes that were actually placed on the table. Some of them relate to multiple crimes.

While the suspect is filling the folder, the investigator is writing the names of the categories on the note sheet. And then to make all of this official, the two players sign this document. The legal part of it is underneath, inside the folder. Afterwards, the two players choose a set of what we’re calling the Miranda rights. They alternate picking a rule, starting with the suspect. These are special rules that can help or hurt the player, so they need to choose wisely and choose rules at the right time.

So once the setup is done, we move to the question and answer phase. During each phase the investigator is allowed to ask three questions about specific categories. They can be straightforward, such as, “Tell me about your favorite hobby.” Or they can ask for more detail like, “Have you ever cried while watching your favorite movie genre? Why and why not?” If the suspect ever feels uncomfortable about answering a question, maybe it’s getting too close to something that might reveal the crime, they can plead the Fifth. So this is where you get you get the use the self-incrimination part. But only a limited number of times; you can’t just say it whenever you want.

Of course, they can do this just to throw the investigator off. It’s all part of the game. The suspect can then answer these questions truthfully, or they can lie. And you may think that it’s easy to fool the investigator by just lying, but after the third question the investigator gets to guess how many of the suspect’s answers were lies or the truth. If the investigator gets that part right, they can gather more information on what you specifically lied about and what you specifically told the truth about [recording freezes for ~10 seconds at 12:15] … I was able to map out self-incrimination and double jeopardy without straying far from the original deal too much. The one I took the most liberties I think with was the Miranda warnings. Instead of them being something set up by “law” in the game, it’s something that the two players need to agree on. But once they do, they’ll need to make sure that they know their rights and when they apply. In I guess the non-game real world, things can wind up poorly if you forget your rights or someone forgets your rights.

I’m looking forward to this whole exhibition. And what I’m really looking forward to is the dynamics of watching people play. And I’m really really interested in seeing what happens when two people who know each other really well start to play. Because the people you know well, you get to know their tells when they tell a lie, or at least maybe you think you do. And then during the game you’re obsessing over them doing small things like tapping their fingers when they answer certain questions. And I want the suspect to do their best to weave a web of deceptions, but one that I guess I’m considering fragile. Because if they’re not paying attention or they’re careless, the investigator will…I guess continuing with the web thing—will pull on a thread and eventually the entire web of lies will collapse.

And I guess I can finish by saying it’s funny because working on this is… When I was working on this and something else, I thought my days of working on games about deception and manipulation were over. But then this entire game is about leading people on and gathering information. And I’m a terrible liar myself. I get super guilty over any type of lie that I tell. So anytime I try and play this game, I try and be as truthful as possible. Which means I’m terrible and I lose. So the overall process for this has been really interesting. And I’m really looking forward to seeing what emerges when people play together. That is it. Thank you.