Kevin Bankston: So, I am the person who is kicking things off with a brief talk to answer the initial question, why is science fiction so important that we’re spending a half day at a think tank talking about it? And at this point it would be good for my slides to come on. Great!

Well we’re here because the imaginary futures of science fiction impact our real future much more than we probably realize. There is a powerful feedback loop between sci-fi and real-world technical and tech policy innovation and if we don’t stop and pay attention to it, we can’t harness it to help create better futures including better and more inclusive futures around AI.

The paradigmatic example of the sci-fi feedback loop is probably space travel. When Jules Verne wrote From Earth to the Moon in 1865 and HG Wells wrote his 1901 novel The First Men in the Moon, they didn’t quite know how we’d get people into space. One author shot his characters off into space with a big space bullet. The other made up a fictional anti-gravity mineral. They didn’t know exactly how we’d get to space but the adventures that they wrote directly inspired a boy named Robert Goddard, who grew into the man who launched the first chemical rocket in 1926.

Just three years later Hermann Oberth, who loved From Earth to the Moon as a boy so much that he memorized it word for word, test-fired his own rocket with his assistant and fellow science fiction buff Werner von Braun who would go on—after an ignoble stint as a Nazi, it should be noted—to become director of NASA’s Marshall Space Flight Center and chief architect of the Saturn V rocket that finally did carry men to the moon 104 years after Verne’s book was published.

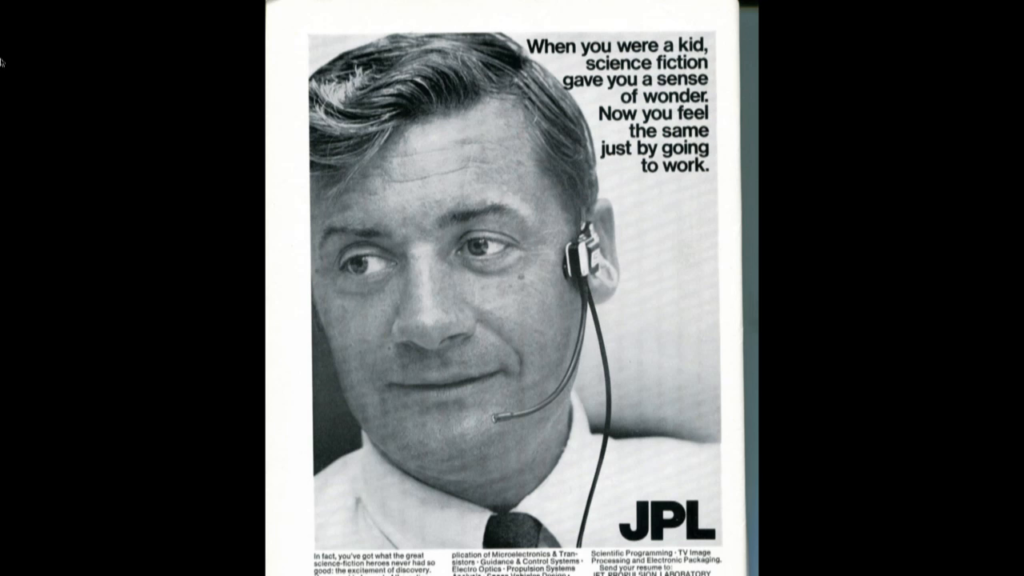

He did that with the help of a younger generation that had been raised on Flash Gordon and Buck Rogers and the novels of people like Robert Heinlein. This is an actual recruiting ad for JPL—Jet Propulsion Laboratories at the time, banking on nerds liking science fiction.

And what they did in turn inspired a whole new generation of more realistic science fiction about space travel like 2001: A Space Odyssey. In fact, director Stanley Kubrick hired two of NASA’s top scientists to spend two years designing his unprecedentedly realistic vision of the future. That team in turn consulted extensively with over sixty technology companies and researchers and experts, with some even getting involved directly in the design.

GE helped envision the space station and the lunar base. Bell Telephone contributed to the design of this video phone booth, which was one of our first popular visions of video chat. And IBM designed several of the spaceship’s control panels and this tablet computer that predated the iPad by nearly fifty years.

Perhaps more on topic for today, IBM also worked on the HAL 9000 computer as did real AI expert, MIT’s Marvin Minsky.

In part because it was so well-informed by real science and tech, 2001 had a unique impact in terms of influencing our modern conceptions of space travel, and personal computing, and AI. The feedback loop in action, if you will. This is especially evident when you look at the influence of HAL 9000, whose capabilities basically set the research agenda for AI researchers in the following decade, setting goalposts on goals that at this point have mostly been achieved. Just like HAL, AI today can play and beat us at games like chess, recognize our voices and faces, read lips, understand and replicate human speech, kill people, and so much more.

Indeed, the fact of this feedback loop of sci-fi inspiring real tech inspiring sci-fi inspiring real tech is so well-documented and established in the space and defense sectors that it’s essentially been institutionalized, with the DoD and DHS and NASA and the like regularly bringing in sci-fi writers as strategic foresight consultants, holding sci-fi story contests or commissioning new stories from established writers to solicit fresh ideas about the future of conflict. And even teaching some sci-fi in military academies. This cottage industry of sci-fi as futurism has in the past decade or two actually been spreading into the private sector, with regular companies, normal companies, like Nike or Home Depot or Boeing working with sci-fi writers as consultants.

Sometimes, the influence of such writers in the real world has been dramatic, and not necessarily for the best. For example in the early 80s, two of the era’s most popular and conservative sci-fi writers, Larry Niven and Jerry Pournelle, organized the Citizens’ Advisory Council on National Space Policy that directly prompted Ronald Reagan, a science buff himself to launch the ill-fated an enormously expensive missile shield product known as the Strategic Defense Initiative, also mockingly known as Star Wars. Here’s an editorial cartoon from the time:

Sci-fi also impacted our emerging cybersecurity policy. When War Games the story of a teenager who hacks into a wargaming AI at NORAD and almost starts World War III—and if you don’t think that’s science fiction come at me—totally freaked Reagan and Congress out, led to a major revamp of how DoD handled its computer security, and also prompted Congress to pass our first anti-hacking law. They even showed clips from the movie in Judiciary Committee hearings, which was crazy.

Of course, when talking about sci-fi’s impact on policy we also can’t skip issues of privacy and surveillance. One book in particular has literally defined the debate for over half a century, although Minority Report has given it a run for its money in recent years.

These privacy dystopias are helpful because they provide us with what science fiction writer David Brin calls self-defeating prophecies. They serve as a warning for what we want to avoid. However, just as often Silicon Valley has read such dark science fiction visions as a design spec for their next big thing. In particular, the near-future information technology-focused sci-fi genre of cyberpunk in the 80s and 90s, exemplified by the classic hacker noir Neuromancer, whose author William Gibson coined the term “cyberspace,” has been deeply influential.

One sci-fi writer who got his start around the same period, this dapper fellow, popular proto-cyberpunk author Neal Stephenson, has helpfully described sci-fi’s influence as less of a direct one-to-one inspiration and more of an invisible magnetic field that roughly orients people’s imaginations in the same technological direction, giving them common ideas and language for communicating about what they are imagining.

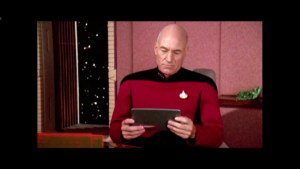

So, you say you want to build something like a communicator from Star Trek, or a tablet computer like in Star Trek: The Next Generation, or even an orbital space station like in Star Trek: Deep Space 9, and everyone knows what you’re talking about and can work together to move in that direction.

Stevenson’s own books serve as a great example, having had a very strong magnetic pull in Silicon Valley. The global VR network of The Metaverse from his own cyberspace classic, 1992’s Snow Crash, was a key inspiration for real VR and AR tech, both then and now (he’s actually still the Chief Futurist at VR startup Magic Leap), and was a big inspiration for a generation of Internet tech folks generally, especially including Google founders Larry Page and Sergey Brin.

The more recent novel, and very bad movie, Ready Player One by Ernie Cline has played a similar magnetic role for VR today. Oculus founder Palmer Luckey actually used to hand it out to new employees, to align them with his product vision.

Similarly, Stephen’s Cryptonomicon, a story about crypto currencies and data havens was according to Peter Thiel required reading at the startup PayPal. Stevenson even played a role in the founding of Jeff Bezos’s space launch start up Blue Origin. The company was born in part out of Bezos’s own lifelong love of sci-fi, especially Star Trek, and his conversations with his old Seattle buddy Neal Stephenson, who he hired as the company’s first employee.

So, these are just a few of the tech billionaires who do what they do because of the technolibertarian fantasies they read and watched when they were 12. You literally can’t throw a rock in Silicon Valley or Seattle without hitting one of these billionaires who is a fan of sci-fi, including this gentleman who is Wozniak, cofounder of Apple.

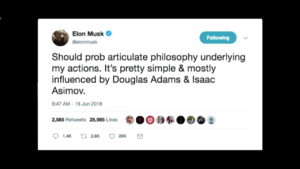

And we still haven’t talked about this guy, the billionaire elephant in the room Elon Musk, who directly attributes his entire life philosophy and mission to the sci-fi he read as a boy. Here’s a tweet referring to Douglas Adams of Hitchhiker’s Guide fame and Isaac Asimov of The Foundation and I, Robot.

And it’s Musk in particular who puts a fine point on I think both the good and the bad of sci-fi’s influence on tech. Standing alone, I think it’s probably a good thing that sci-fi inspired this guy to dedicate his life and his billions to getting us off of fossil fuels and off of the planet. But as you may have noticed there’s a certain homogeneity to the people I’ve mentioned so far. This feedback loop has been a somewhat closed loop that reflects the lack of inclusion in both the fields of tech and sci-fi. A series of privileged white men inspiring… Sorry Siri. It…she doesn’t like what I’m saying and she’s trying to get in the way. A series of privileged white men influencing privileged white men influencing privileged white men, with grand wish-fulfillment narratives of great men changing the world through their inventions and their adventures.

Too often missing from this feedback loop and relatedly, from the field of AI, has been a recognition of and an inclusion of and a centering of the lives and perspectives of people—and not just individuals but communities—who’re not middle-class cisgendered white men mostly from the American West Coast. Or put another way, science has too often held up people like this guy. Um, I’m a Picard fan myself. Which is why I was so heartened to see Nora Jemisin—NK Jemisin’s—historic victory last year at sci-fi’s Oscars, the Hugo Awards. Not only the first black author to with the best novel Hugo, but now the first author ever to win it three years in a row, for her Broken Earth trilogy. Sidenote: I was equally heartened to see Malka Older who is with us here today nominated for the best series Hugo this year for her amazing Infomocracy series.

Miss Jemisin has been a tireless voice for inclusion in sci-fi literature and sci-fi fandom, and it’s with a few inspirational words from her speech that I’m going to close this talk with, words that could just as easily apply to the field of AI.

“I look to science fiction and fantasy as the aspirational drive of the Zeitgeist: We creators are the engineers of possibility. And as this genre finally, however grudgingly, acknowledges that the dreams of the marginalized matter and that all of us have a future,” not just Elon Musk; that’s my addition not hers, “so too will go the world. Soon, I hope.”

So, thank you all for coming. We are going to start our first panel which I think is going to sound some of the same themes as my talk. And so I’d like to introduce our panelists now to talk about AI policy in reality. So folks come on up.