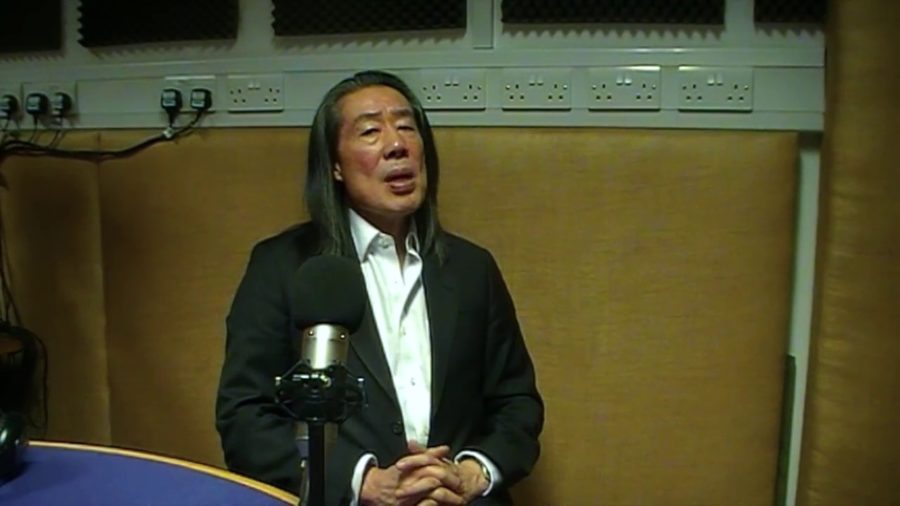

Stephen Chan: After World War II there was a great drive towards secularity and modernization in a range of Islamic societies. A number of Islamic states had revolutions that turned them in a particular post-war direction. And in this post-war direction the emphasis was on two key things. The first was modern development. In this sense it meant catching up with the metropolitan Western world. And the second driving force behind all of this was the assumption that this would be best done by instituting secular states. It wasn’t that religion was being done away with, but religion was made deliberately subordinate to the institutions of the state.

Now, this was a very very bold move. It was something that took place not only in Middle Eastern Islamic states but in far-flung corners of the world—in Indonesia for instance, underneath President Suharto. Certainly in the Middle East what you had were the very very radical revolutionary steps taken by the free offices underneath Colonel Nasser in Egypt. And you had the efforts of the Ba’ath party in Syria and in Iraq to accomplish something of the same vision for the future. In fact at one point in time there was a proposition on the table that Egypt and Syria should form a United Arab Republic, and the co-joined country would go forward along these lines of secular modernity.

This was very very bold, but it was not something which was new. Basically what these countries were seeking to do was to emulate the original template established after the First World War in Turkey. But there, the Turkish vision for the future was driven not only by a desire for secular modernity but also a desire to rescue something of a national project. Because in World War I, the Ottoman Empire had been defeated. It had been regarded by the Western allies as a decadent power, and this was not true. Because what you had for instance in the writings of someone like Lawrence of Arabia in his great book Seven Pillars of Wisdom, where you had exploits conducted by Lawrence against the Ottoman army. You had accounts of every time that Lawrence and his Bedouin guerrillas blew up Turkish or Ottoman railway lines, communication and telegraph poles, the very next day the Ottoman soldiers and engineers would be out repairing them. There’s no question about a certain technological capacity. They fielded a modern army that in fact at great cost, but also at even greater cost to Allied troops at Gallipoli, had defeated Allied armies.

But the idea of decadence was that the Ottoman governmental system was antiquated. That even if they were the artifacts of modernity and technology, the system of government could not continue to promote these in a dynamic way because it was looking towards the past. So the idea of decadence very very much accompanied the picture of the Ottoman part of the world, which at one point in time had been a vast empire.

The idea of defeating the Ottomans along with Germany (it had been a German ally) was also accompanied by the idea of reducing it so it could never be a threat again in the future. And so much of the territory that was occupied by the Ottoman empire was taken away. They became colonial possessions, for instance British, the French. But also parts of it went to Iraq, part of it went to what became known as the Transcaucasian states surrounding Russia—the Soviet Union. And what emerged after prolonged negotiation was a smaller Turkey.

Now, the idea that once upon a time Turkey was larger, once upon a time Turkey had greater geographical spread, and particularly given that many of the surrounding areas are Turkic in terms of their language affiliation, that has never left the Turkish imagination. But Atatürk, who launched a revolution after World War I—he was the leader of the so-called Young Turks. Young Turks, that’s a phrase which has entered into our own usage in English language. People who are innovative, revolutionary, wanting to set up a new start. This idea of making that new start, taking modernity even further forward than had been possible before, but doing so without the decadent and degenerate constraints of a conservative inward-looking Islamically-based society. Keeping Islam but subordinating it to a very strident, almost militant secularism to be safeguarded by the army.

Younger officers, younger technocrats, this was the vision of Atatürk. This is what was emulated by Egypt, Syria, to an extent by Iraq, by Indonesia after World War II. But the Turkish experiment was a very very significant one. And it was one that the army in particular very jealously safeguarded as its constitutional mandate for many many years into the future beyond Atatürk, right up to almost the present day.

But although Islam was subordinated to the institutions of a secular state, it never went away. It remained very very much as part of the culture of Turkey. A very very difficult type of Islam in the sense of its efforts to fuse elements of both Sunni and Sufi Islam together. The reverence given to people who were essentially Sufi poets, like Emre for instance. People like the other great writers of that 13th century period, who were charismatic in terms of the visions that they tried to write about. The cultivation as a cultural artifact of the Whirling Dervishes, a group practice of transcendental linkage with God. Very much a ceremonial Sufism, which sat ill at east with a strident, militant, and text-based Islam, which is the hallmark of very strict Sunni belief.

So this uneasy blend of Islam, all the same subordinated to the state, kept bubbling away underneath the surface. So that when we had the triumph in recent days of Erdoğan and his party, and finally what was regarded as a mild and moderate Islamic party took charge of Turkey up to that point in time, since World War I a secular state, everyone wondered what the future would hold. Would it become strident? Would it become militant in a jihadist way? Would it become part of the great problems of the Western world and its relationship with the Islamic world? Or could it remain a bridge between the two, given the great modernity that a very great deal of Turkey has managed to achieve?

Now in fact, one of the hallmarks of the Erdoğan government, quite apart from accumulating more and more power in the person of President Erdoğan himself, has been the desire to reestablish the kind of outreach of the Ottoman Empire. The slow but very steady involvement of Turkish foreign policy in Middle Eastern theatres of conflict, in Syria for instance, in the battlefields of Mosul for instance, and trying to be a power to counterbalance Israeli outreach in the Palestinian area, and trying to make incursions against Russian expansionism in the Transcaucasian states, all of this looks to a vision of Turkey as recapturing if not in geographical terms but certainly in influential terms the kind of outreach that was possible during the Ottoman period. Mosul for instance, the battleground now between ISIS and a coalition of forces including Turkish forces in the background, was once part of the Ottoman Empire. It is now part of Iraq—it is now contested. But I think the sense in Turkey, certainly underneath Erdoğan, is that this was once part of the Turkish provenance in that very key strategic and critical part of the world.

But the percolation of Islamic influence in society at large that allowed Erdoğan to rise to the top in a wave of popular democratic momentum was probably accomplished by a very very curious scholar and thinker called Gülen. Erdoğan now has essentially outlawed Gülen. The recent coup attempt in Turkey was blamed fairly and squarely on the followers of Gülen. Gülen was seen as the dark force that animated this uprising against Erdoğan.

But without Gülen and his influence in almost every section of society, this percolating Islamic influence, there would have been no Erdoğan. So whether or not this was a power struggle to settle scores of debt that were accumulated in the past, whether it was a power grab for one man only at the expense of the other, or whether there was a real difference between the two in terms of political or even doctrinal terms, remains open to debate.

Certainly what Gülen stood for is something worth remarking upon. The terms like “moderate Islam” are overused and have been overused to the sense of being banal. But he really did stand for a scholarly version of Islam which was ecumenical and compassionate. So that a very great deal of the social work accomplished by the Gülenist movement was very much the kind of public good that municipal councils and governments could not provide. When I was last staying in Istanbul, for instance, the park outside my apartment was looked after by Gülenists who would give up their time voluntarily to do something as simple as watering the plants. Everywhere you went you could see the social good that they were accomplishing, and you could feel the good will that this was building up.

But the idea that Islam could be, in a scholarly and thoughtful way, a bridge between East and West was something which was a hallmark of what Gülen stood for. His exile now, in North America, is almost emblematic of this kind of bridge. A bridge at opposite ends of which he felt at ease. His outlaw and his exile from Turkey is a big risk for Erdoğan. He may consolidate power in his own person and in the office of the president. It’s not as if the president, like a king, wears no clothes. But the underpinning of all of this, the way he rose to power, is it going to be a case of the fact that the king has no underwear?

Further Reference

Religion and World Politics course information