Mojca Pajnik: Good evening. I will discuss aspects of transnationalism by mainly exploring the notion of citizenship. Citizenship as a concept and also as a practice normatively actually stands for activity in the public sphere, activity in the political field, and it stands for membership in a political community of equals. So this is an aspiration within the notion of citizenship that we sometimes forget, because when we think of citizenship nowadays, we mostly see it as a contested notion for it being reduced to an administrative criterion that is actually selectively differentiated: inclusion in, or exclusion from the nation-state membership, from privileged membership of Western nation-states.

I would argue that postmodern—so contemporary, or supposed democratic societies that are characterized by what could be called the hollowing out of democracy, the hollowing out of democratic potential, have actually enthroned citizenship as passport identity; we’ve already heard in James’ talk. And enthroning passport identity seems today… It has been reproducing a never-so-profound differentiation between those with the right passport and those with the wrong one; those from the West and those constituting the rest; those constituting the “we” and those marginalized as the other. And you know, we could go along making similar analogies.

I will now discuss how such differentiation has been reproduced and what it brings. I will call differentiation principles and I will explore basically how nation-states have actually enthroned citizenship as passport identity; how nation-states have actually been robbing the potential of citizenship from its equality-oriented aspirations. And if we bring migration in this discussion, looking at how migration is actually managed today, how nation-states are managing migration, one would observe that migration is predominantly framed or understood as a sabotage. It is understood as an unprecedented breach of bordered territoriality and a breach of docile labor.

So basically we are seeing when we look at the reactions of the nation-states to migration, to mobility, we are seeing that this nexus—migration/mobility—is actually conceived as a threat to sovereignty.

Consequently, the primary concern of holders of power is actually how to make mobile subjects—so-called ungovernable subjects—how to make them governed. So turning mobile subjectivities into governed individuals, basically this is the way to control mobility. And this is actually also the way to subordinate mobility to fit various nationalist ideologies or labor market productivity goals.

I will now discuss these four differentiation strategies that are facilitating such goals. The first strategy can be called categorization of citizenship or categorization of people.

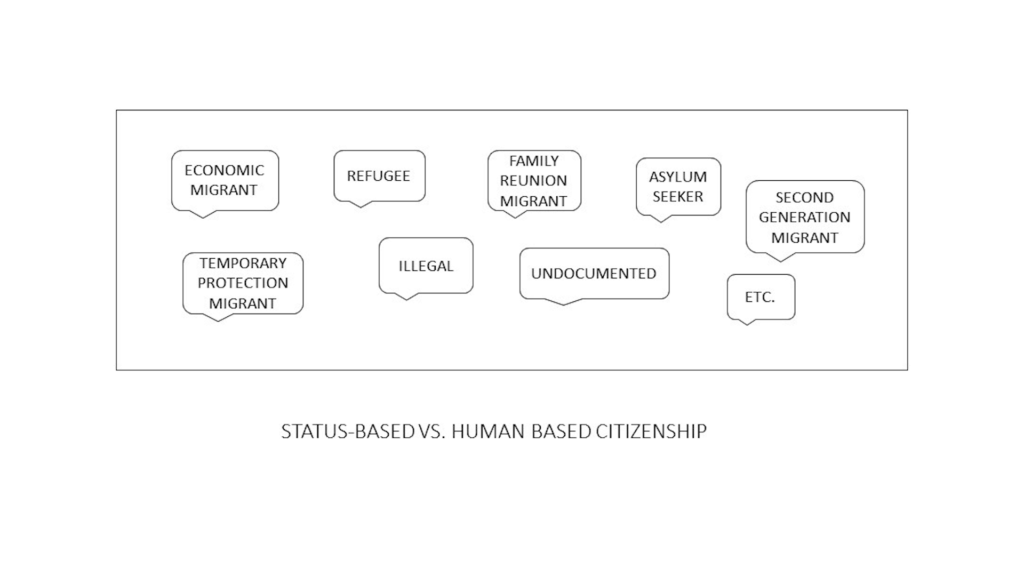

Taking the example of migration management, we can see how states have produced meticulous categorization of migrants into various groups. So we have asylum seekers, refugees, illegal migrants, family reunion migrants, undocumented migrants, work migrants, and the list goes on. Some of these categories when you look at them more closely have a legal backup. They have appeared as legal categories and they are by law actually used to limit human rights, to limit mobility, for some of the “categories.” For example the case of the “category” of the refugee or the asylum seeker.

On the other hand, we see some of the categories that do not necessarily have a legal backing but that have however found widespread legitimization in political discourse and the related public and media discourse, where they function as metaphors for “migrants,” for those over there, for the second-class people—for example the category of an economic migrant, or the category of an illegal or an undocumented migrant. It is not actually a legal category per se but has been used widely, firstly in the political and then in the media discourse to again reproduce differentiation.

These categorizations, when we look at them what do they tell us? They point to prioritization of status-based citizenship versus what could be called human-based, what could be viewed as human-based citizenship. And by doing so they’re actually grounding the legitimacy of the people’s existence on the predescribed statuses, where one’s life is actually dependent on the holding of a specific status or the lack of a specific status.

So by doing so, categorization regimes have actually produced categories of underpeople who are viewed in the words of the rising populist political parties across Europe but also globally, who have for example declared that of multiculturalism as “impossible subjects of integration.” This is how the mainstream political speech in the predominant political elite goes. So migrants are being viewed as impossible subjects to be integrated. They’re viewed as such for the ascribed difference, the ascribed allegedly different culture, different customs and so on that obviously does not fit the norms of the civilized West.

The second differentiation strategy that I want to address can be called the contractualization of citizenship. Let me make an example from migration studies. If a female migrant, a woman migrant, if we look at her we see that she’s dependent on the set of conditions that go along with her specific status, if she seeks asylum, then statistics tell us that she has less than 1% chance of being admitted into a status of refugee. Once getting the status of a refugee, the host country—so the state where she currently lives—decides the conditions under which she can work, whether she can work. The state defines the conditions if and under what terms she can get education and so on and so forth.

The system is actually conditioning her life with more…it’s inventing new requirements for her to finally be able to fit in but this actually never happens. I like this Balibarian notion you know, “once a migrant always a migrant.” So the system has been reproducing the category of migration.

As an example I have thematized the creation of migrants as wasted precariat, wasted precarity, in line with Zygmunt Bauman’s notion of the wasted humans, arguing that migrant precarization is orchestrated at the intersection of immigrant status first. Second, the governance of migration and labor. And third, the features of the industries that actually employ migrant workers. We can see that the function of this triangulation, the contractual, illusionary inclusion of mobile populations, is actually to create different subjects of labor. This allows nation-states to carefully select the wanted from the unwanted migrants, and we have been seeing a trend globally of channeling migrant labor force into the so-called 3D jobs—so dirty, dangerous, and demanding.

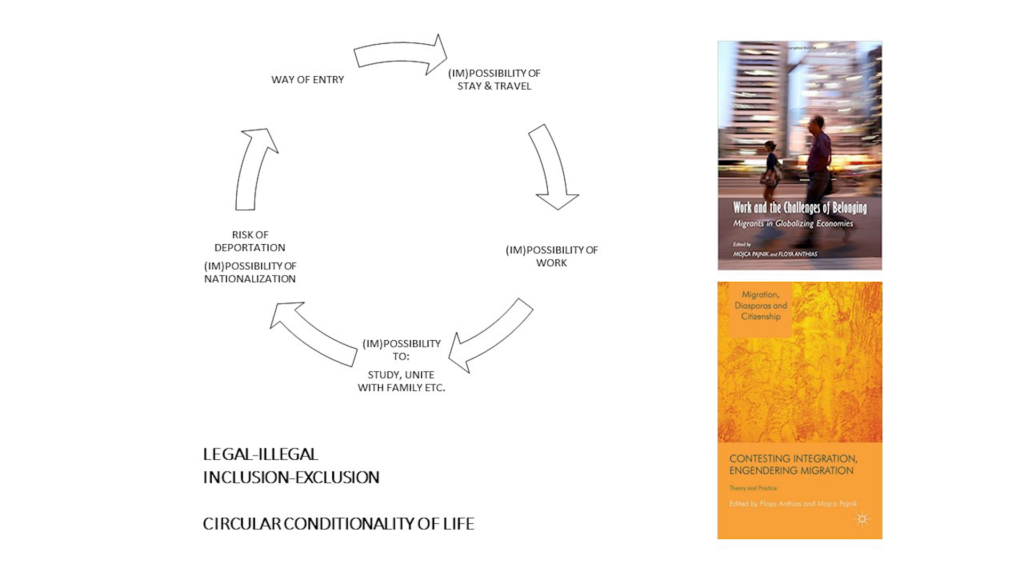

In these books we have referred to the circular conditionality of migrants’ life that is actually bluntly pointing to what contractualization of citizenship actually means. Without a permit for work it’s not possible to obtain a residence permit. If one does not have a residence permit, then your working possibilities are limited. If you don’t have a residence permit you’re not admitted to be fit for citizenship. If you don’t have citizenship, then you cannot be part of the medical insurance schemes, and so on and so forth.

The third strategy of differentiation that I want to discuss can be called crimmigration. Generally, crimmigration points to the convergence of migration laws and punitive laws. Or in other terms, crimmigration exemplifies contemporary trends of criminalization of mobility.

Various strategies can be observed as within this notion of crimmigration. One is the strengthening of border regimes while borders, as I will try to show a bit later, can have very different meanings. One can play around the borders, but historically we can admit that borders have been an institutional means for safeguarding the rule of exclusion. The territorial borders in this context appear as spaces where differences are reproduced or as spaces where people are divided and sorted. And consequently borders in this context appear as manifestations of hegemony and its pressure to normalization.

The power to admit or to exclude non-citizens is inherent in border sovereignty, and lately if we look at the European context but also globally, it seems that we are witnessing the hysteria of bordering. For example rebordering at the sea, building double or triple fences on land, together with soft, electronic fingerprint-related bordering that are all strategies that are being legitimized as securitization policies. But we clearly speak here of state securitization, and the opposite would be human securitization. So borders actually here, by pursuing security and by reproducing the dangerous other, can appear as a mechanism of institutional racism that is actually eradicating, in Rancièr’s terms, “the difference between the police and politics”—politics, policies, has become policing, basically.

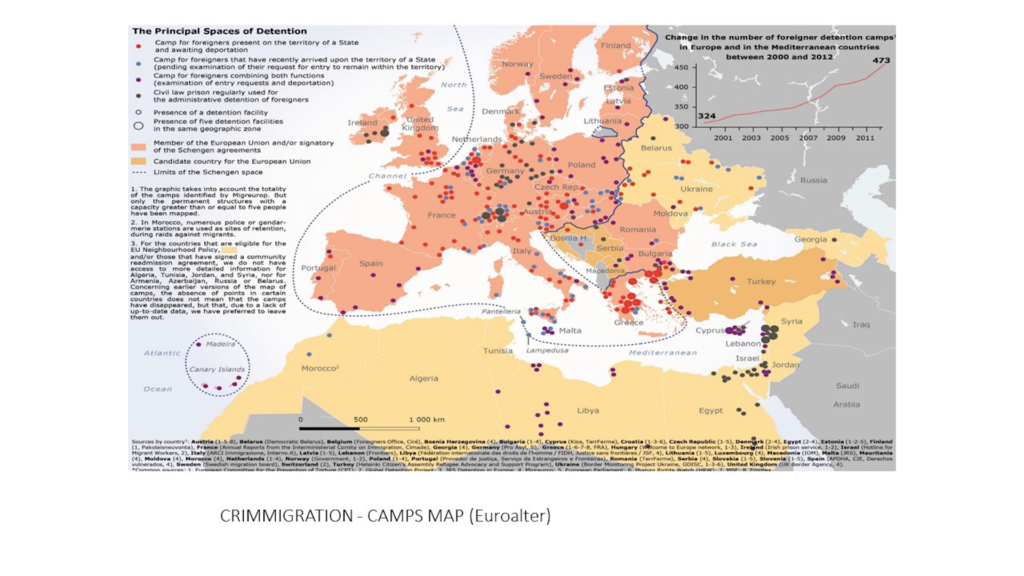

Other strategies of bordering include camps. Detention camps, refugee camps. The map here shows the steep rise in the number of foreigners’ camps in the last fifteen years in a European context. We know that camps have been gentrified, built at the outskirts usually of life, and that as Foucauldian islands of the [fools?] are usually situated at the outskirts of urban settlements. Often they do not have Internet facilities, medical care, legal advice. All these services are limited. Meaning that individuals who are living there in a way have been robbed of their dignity, and the bordering of the camps, people have been living with “bare life” in the terms of Giorgio Agamben.

And yet, we can see when we look at the political discourse that camps have been celebrated as solidarity or as assistance of the globalized West, which to put it mildly can be viewed as language manipulation.

I will move to the third strategy of differentiation that I want to address, that can be called externalization of borders. The example is the state agreements. For example the European Union a couple of years ago had made an agreement with Libya, followed by an agreement with Morocco. Or if I mention the recent agreement of the European Union and Turkey, according to which Turkey has been keeping in camps more than two million people at the doors of the European Union. Here we can see that the EU from the position of the rule-maker actually has been colonizing the east and the south as the rule-taker by adopting agreements to actually stop mobility or preventing mobility, before mobility reaches the borders of the European Union.

Populism and the Web: Communicative Practices of Parties and Movements in Europe (Pajnik & Sauer, 2017)

By now I have mostly addressed the political, the legal ways of constructing transnationalism. But there is another way—which James has also mentioned before—that I think is reproducing the outcomes, and that is by means of political, by means of media discourse, and we are seeing when media are reporting about migration, the spectacularization of this phenomenon, which is largely an adopted populist strategy both being adopted by the political elite and the mainstream media.

When the political elite of the European Union began to proclaim a security threat by so-called “massive” migration in 2015, 2016, during the functioning of the Balkan route, they conveniently operated with the category of an economic migrant. It was interesting to see how “he,” the masculinity was very proclaimed here—was symbolizing a threats penetrating the allegedly ethnically homogeneous nation, threatening domestic workers, taking away their jobs and social security and so on.

While on the other hand, when the EU wanted to show its humanitarian, you know, more solidarity face, then the category of the refugee has been introduced into the discourse. And this category actually had this compassion at the moment. The discourse was changed. Women and refugee children came into the debate. “We need to feed the children, we need to take care of them,” but here we saw that the tolerance ended. So not hungry anymore, we saw in the political discourse that they should move forward or they would be, according to the statuses that we have discussed before, deported. We sympathize but if I quote the Slovenian Prime Minister, “our integration capacities are limited.” He was saying this and the media have been repeating this.

In the concluding remarks I would like to go back to the idea of transnationalism and citizenship. And we can see that both these concepts, both these ideas, have become in the last ten or fifteen years keywords in claims to surpass the state-centric perspective on territory, state-centric perspective on the understanding of the state and on human life. Still, we have shown how significant formal citizenship is [when one?] fails to fit a specific category, when a status is denied. So how this reproduces precarity in the hierarchy of an unequal citizenship market.

Transnationalism I think has the potential to actually enact and to stimulate a transformative agency…I mean stimulating us to think about the multilayered subjectivities contesting the idea of scalar identities or of nested identities. And migrants are embodying I think these ideas.

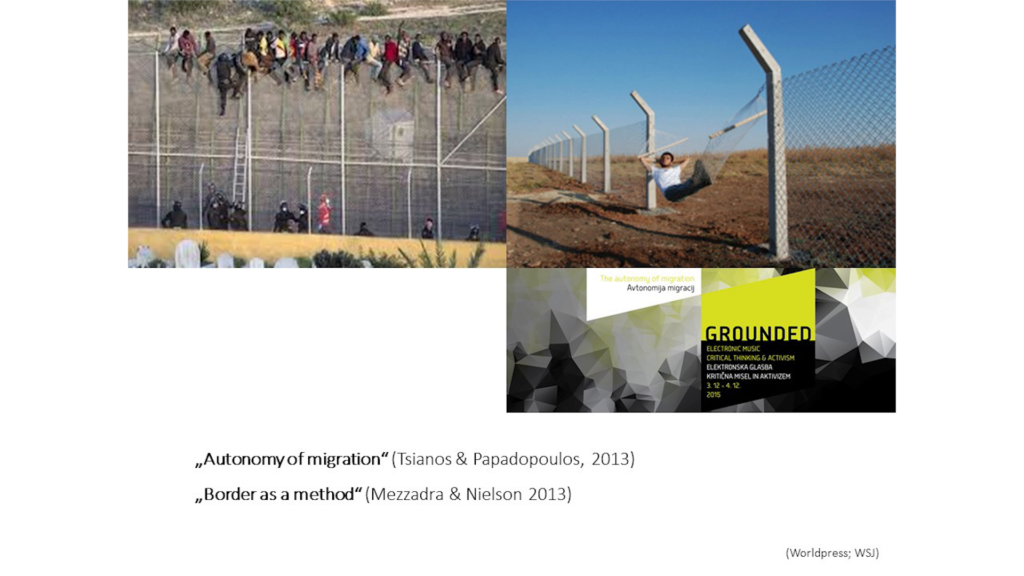

Autonomy of migration (Tsianos & Papadopoulos, 2013);

Border as a method (Mezzadra & Nielson 2013)

I would like to refer briefly to the literature on autonomy of migration that has been put forward about a decade ago. This literature is interesting because it has taught us to view subjects on the move not as victims, obviously, but as so-called “nomads of the present” who are disrupting certainties, who are breaking the rules, not at least who are crossing the borders, who are rupturing the status quo and by doing so who actually bring possibilities for critically rethinking contemporary situations and also think of future aspirations.

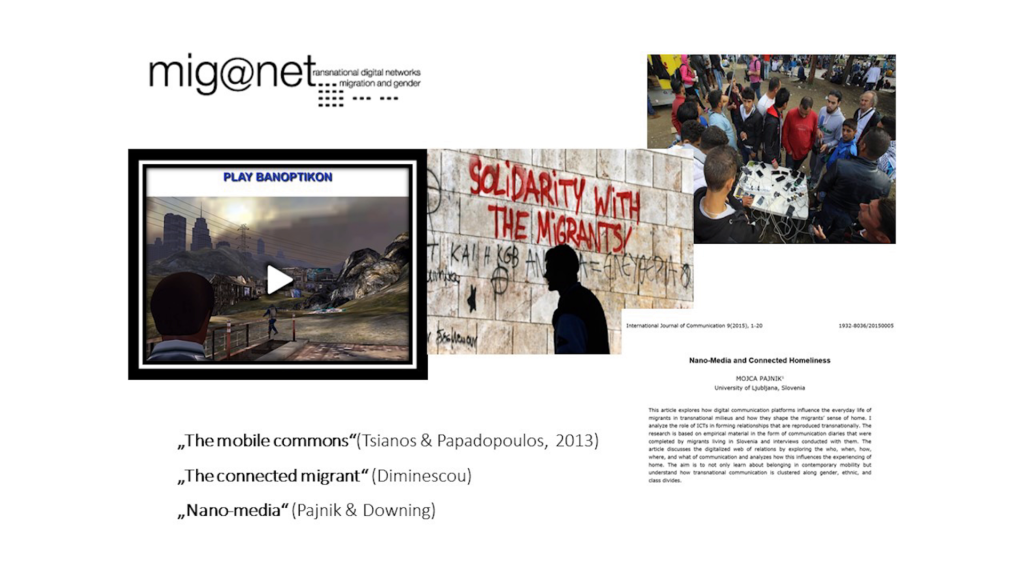

The mobile commons (Tsianos & Papadopoulos, 2013);

The connected migrant (Diminescou, 2008);

Nano-media (Pajnik & Downing, 2008)

My Greek colleagues from the MigNet project that was a project on migration, Internet, and gender have produced a video game, Banoptikon, which simulates migration situations which take place at border crossings or in rural areas in cities, but above all which affect human bodies, as we’ve already heard today.

Bodies are actually becoming the subject on which control is applied, and bodies today actually remain the basic topos also to counteract control. And these bodies, the transmigrant, the transnational bodies don’t fit, obviously, the typical picture of the victim, or migrant as a victim, or the typical picture of migrant as a perpetrator, as being a violent person that is often reproduced in the political discourse.

Just one minute to stop, with some new concepts that I think are challenging and that are related to the utopias of transnationalism. For example the idea of the mobile commons. Mobile commons is actually addressing mobility populations who are exchanging knowledge on mobility. We are seeing migrants that actually exchange knowledge about border crossings, about routes. We see migrant tactics that are escaping surveillance regimes, for example that escaping fingerprinting. We see migrants practicing connectivity by using nanomedia, by using various technological devices, as well as mouth-to-mouth strategy which can which can embody the notion of the connected migrant. So it’s far from migrant being a victim, but is producing another set of thinking where we see migrants as active subjectivities that are actually pursuing the idea of world citizenship, “weltbürgerrecht” in the terms of Immanuel Kant, which is meant to signify not a bright utopia or an ideal life that is lifted away or that has nothing to do with reality. To the contrary, we can see this transmigrating subjectivity actually reinventing what can be seen as worldliness of people, right, where people are judged by human security and not to by nation-state security. Thank you.